5 years on from the introduction of Scotland’s pioneering Minimum Unit Pricing policy (MUP), which made it illegal to sell a unit of alcohol for less than 50p, Public Health Scotland published the results of a comprehensive evaluation. This evaluation drew on the findings of 40 individual studies and concluded that overall MUP had a positive impact on health outcomes, particularly in the most deprived areas, while finding no substantial negative impacts – as some opponents of the policy had predicted before its introduction. The evaluation did highlight that MUP appeared to have had limited impact on the drinking of dependent drinkers, emphasising the need for well-funded and accessible specialist alcohol treatment services, but overall MUP has achieved its principal goals. Which invites the question of where next for the policy?

When first introduced, MUP came with a sunset clause – if the Scottish parliament didn’t vote to keep the policy after the evaluation evidence was published, then it would be withdrawn. At the same time, the government are also reviewing the level at which MUP is set. On 20th September the Scottish Government launched a consultation on the continuation of MUP, which stated their intention not only to keep MUP, but to raise its level from 50p/unit to 65p/unit. This decision was at least partly informed by new modelling work from my colleagues and I at the University of Sheffield. So what does this modelling show, and does it support this proposal?

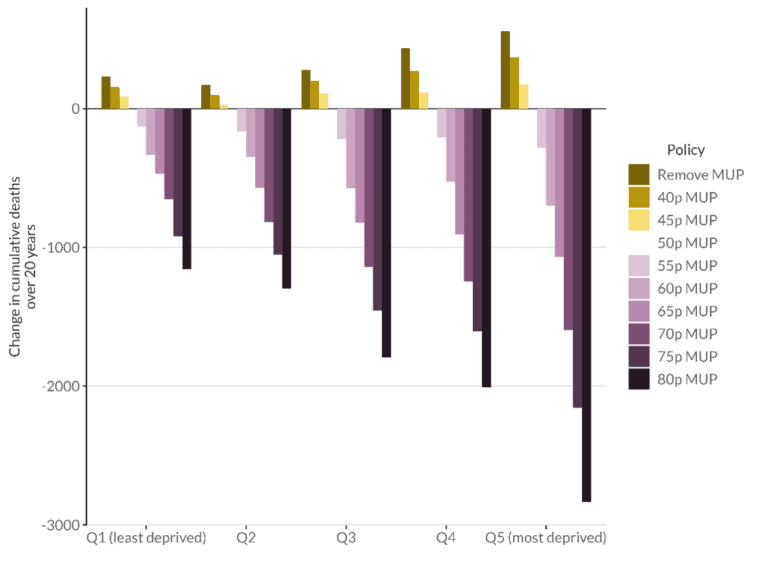

Our new report first looks at the impact of raising the MUP threshold from its current 50p/unit level, lowering it, or removing it entirely, assuming that levels of alcohol consumption and alcohol prices have remained unchanged since 2019. This analysis shows that a further 10p increase in the MUP level would lead to an estimated 18.6% reduction in the number of people drinking at harmful levels (more than 35 units/week for women and 50 units/week for men), 2,483 fewer deaths, 26,644 fewer hospital admissions, 78,150 fewer years of life lost and save the NHS £36.7million over the following 20 years. We also estimate that these impacts are greatest in the most deprived groups, leading to a further reduction in health inequalities. In contrast, removing MUP entirely is estimated to lead to 1,669 additional deaths, 22,179 hospital admissions, 58,348 years of life lost, cost the NHS £26.4million over 20 years and increased health inequalities.

Modelling changes in all-cause mortality over 20 years for different changes to the MUP threshold, by deprivation quintile.

Whilst these figures provide a compelling argument for the public health benefits of raising the MUP level, we know that the underlying assumption that everything has stayed the same since 2019 is not true. In reality the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent high levels of inflation have had a significant impact on alcohol consumption and prices. In the report we also explored the likely impact of both of these factors.

Analysis of alcohol consumption data suggests that moderate drinkers in Scotland drank less during the initial year of the COVID-19 pandemic, while heavier drinkers drank more on average. This ‘polarisation’ of drinking is something we have also seen in England and is likely to be a major factor in the substantial recent rises in alcohol-specific deaths in both countries. The new report looks at the potential longer term impact of these changes in alcohol consumption and finds that, even under the most optimistic assumptions about how drinking patterns revert to pre-pandemic levels, we could expect 663 additional deaths, 8,653 hospital admissions, 22,122 years of life lost and an increase of £10.9million to NHS costs over the next 20 years. Worse still, this burden is estimated to fall disproportionately on the most deprived groups, suggesting a further increase in health inequalities as part of the fallout from the pandemic.

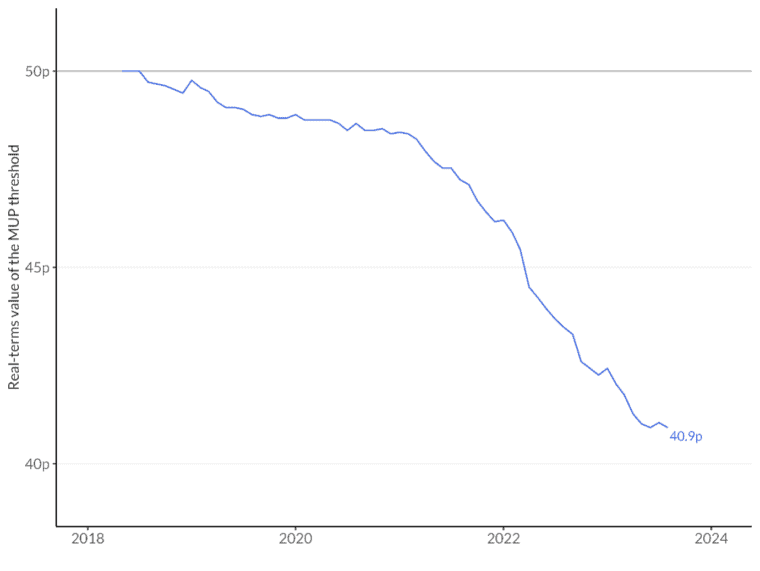

When talking about policies that affect the price of alcohol, it is always important to consider the effect that inflation has on those prices. This is particularly true when inflation has been high, as has been the case in the UK since 2021. This inflation has eroded the real-terms value of the MUP from 50p/unit in 2018 to 40.9p today. To put this another way, the current MUP threshold would have to be 61.1p to have the same effective value as 50p had in May 2018. As a result of this erosion, we estimate that alcohol consumption in Scotland is 2.2% higher today that it would have been if the MUP level had been adjusted in line with inflation each year. In the longer term, maintaining the MUP level at 50p without adjusting for inflation is estimated to lead to 1,076 more deaths, 14,532 hospital admissions, 37,728 years of life lost and an additional £17.4million in costs to the NHS by 2040, compared to a scenario where it was linked to inflation.

This new modelling tells a clear story: MUP has worked to reduce harm, but the effects of inflation will wipe out many of those gains if action is not taken to adjust the MUP threshold. An increase to 61p/unit would be needed just to maintain the effectiveness of the original policy (not accounting for further inflation between now and the date that any increase comes into effect). Meanwhile, changes in drinking behaviours during the pandemic have contributed to an increase in alcohol harms, strengthening the case for further policy action to tackle them. In this context, while raising the MUP threshold to 65p is certainly a step in the right direction, it is not quite the dramatic increase it may initially appear to be.

Written by Colin Angus, Senior Research Fellow at the Sheffield Alcohol Research Group within The School of Health and Related Research.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.