The wine industry is lobbying hard – or “hell-bent” as the Wine and Spirit Trade Association (WSTA) says – to retain a system where tax per unit of alcohol reduces as wine increases in strength. This goes directly against the objective of the alcohol duty reforms introduced in August 2023, and appears to be an attempt to alarm and confuse its members, policymakers, and the public.

So what is the ‘wine easement’ and why is it bad for public health?

The wine easement

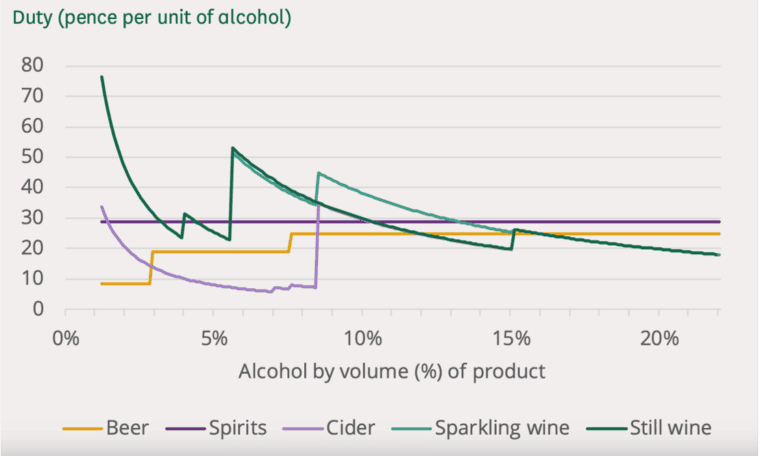

The reform of alcohol duty aimed to simplify an outdated and overly complex system. By taxing all products by strength, the new system aimed to have fewer distortions, reduce the administrative burden on producers, and support public health by incentivising the production and sale of lower strength drinks. It is clear from the following chart that there were major inconsistencies and distortions in the previous system. Bringing wine and cider into line with beer and spirits – which were already taxed on strength – was an important objective.

Many organisations welcomed the reforms at the time, with the British Beer and Pub Association stating that: “Our duty system was long-overdue reform to better incentivise the production of lower-strength products and nudge consumers towards them”. The Institute for Fiscal Studies wrote that the reforms were a “welcome step… Moving to a system that taxes all drinks in relation to their alcohol content is sensible, while having higher rates on stronger products targets heavy drinkers.”

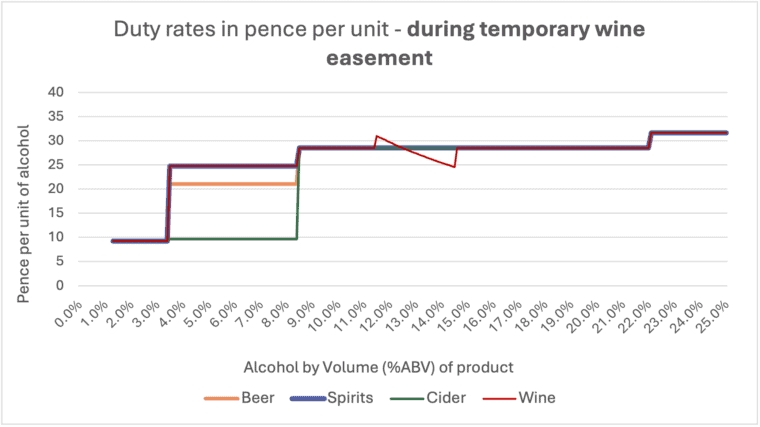

An 18-month postponement of the new system, called an ‘easement’, was applied to most wine products to give them time to adjust to the new system. This means that between 01 August 2023 and 01 February 2025, wines with strength of 11.5-14.5% ABV will be taxed as if they were 12.5% ABV. This range accounts for about 85% of the wine sold in the UK. With current duty rates, it means that wines in that range all pay £2.67 in duty, continuing the favourable tax treatment for stronger wines.

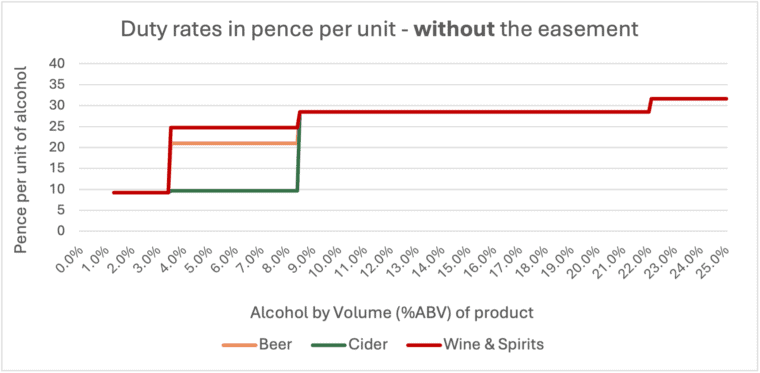

Using the current rates, it’s clear to see that the wine easement creates its own distortion. The first chart below shows duty structures without the easement, which will be the case from 01 February 2025, the second shows them with the current easement.

Why would this go against the public health objective of the reform?

As the Treasury has made clear, one of the main objectives of the reform was to improve public health, by giving a commercial incentive to producers to reduce the strength of their products. Put simply, if a producer lowers the strength of their drinks, they pay less alcohol duty, meaning they can make more profit or offer lower prices to consumers. From a public health perspective, consumers would drink lower strength drinks and this would reduce their risk of a range of alcohol-related harms.

This incentive to sell lower-strength drinks has already taken effect for some beer products. For instance, John Smith’s Extra Smooth recently reduced its strength from 3.6% to 3.4%, bringing it into a lower tax band and saving many millions of pounds for the brewer and, crucially, reducing health risks for consumers. And Concha y Toro, the largest exporter of wine in Latin America, is planning on reducing the strength of its Isla Negra products sold to the UK from 12-13% down to 10.5-11%.

The WSTA claims that even with the easement “wine is already part of a strength-based system, it’s just pinned to a particular point”. This clearly isn’t the case, as the chart above shows.

There is currently no incentive for producers of almost all of the wine sold here to reduce strength. And the strength difference in that band is significant. Wine consumption accounted for 30.6% of the pure alcohol consumed in the UK in 2022.[i] With 1.77 billion bottles of wine consumed in the UK every year – and assuming an average strength of 12% ABV – if 85% of those reduced their strength by 1%, we would remove over 1 billion units of alcohol from consumption. Reducing the strength of many wine products would lead to reductions in alcohol consumption and subsequent harm. As alcohol-related breast cancer can be caused even at low levels of drinking – and wine is consumed far more by women than men – if wine producers were to reduce the strength, it would likely lead to reductions in alcohol-related female breast cancer cases.

Increasing red tape

The main criticism of the new system from the WSTA and some wine merchants is that it increases the administrative burden on wine sellers and will therefore incur additional costs. Hal Wilson of Cambridge Wine Merchants said that the new rules would require checking and recording the alcohol content of nearly 90% of the bottles it bought, something that would be “unviable” for his business.

To be clear, there will be an increased burden for wine merchants. Previously – when duty was based on the volume of liquid – they could simply group products by the size of the container. Under the reforms they will have to know the ABV of each bottle and pay the appropriate duty. That’s manageable but is definitely a new cost.

The wine industry manages to meet varying labelling and duty requirements all over the world, so producers will be well used to providing retailers and wholesalers with the information they need, including the ABV. For instance, as the World Health Organization states: “The top net importers of wine are, in order, the United States, China, Japan, Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany and the Kingdom of the Netherlands.” Each country has varying requirements, for example China requires specific fragrances, colour, and sugar content.

Perhaps politicians should not be pushing the ‘reduced administrative burden’ argument so strongly in the face of conflicting evidence. Yet ultimately, decisionmakers must decide whether an increase in red tape for the wine industry is outweighed by the clear health benefits of the reforms. The WHO also states that: “A country that is a net importer is likely to see an improved balance of trade from both a global and a domestic decline in alcohol consumption. This can have a positive impact on employment, as the switch of expenditure to other goods and services tends to boost the domestic economy and local jobs.” So reducing the consumption of imported wine – whether due to the additional cost of admin for sellers or changing consumer habits – would likely have a positive impact on the UK economy.

But isn’t it hard to determine the strength of wine?

Using a commerical incentive to encourage the production of less strong alcohol does raise the question of how easy it is to refomulate products to meet specific strengths, with the WSTA saying that it is unfair for wine to be taxed by strength because “only wine can’t dictate its ABV”. Climatic conditions do significantly affect the strength of wines, because hotter weather means more sugar in the grapes, meaning more sugar to be converted into alcohol. That is why English wines tend to be around 11-13%, whereas the South of France often produces wines around 15% or more. Interestingly, producers in cooler countries have added sugar to products for a very long time – a process called chaptalization or enrichment – to increase the strength of wine. This is an essential process for the production of Champagne.

In terms of reducing the strength, winemakers have been doing precisely this for many years now, due to changing drinking habits – people wanting less strong wines – and climate change. Methods include: stopping fermentation and leaving residual sugars and lower ABV; picking grapes earlier so they are not as ripe and have less sugar; and various mechanical processes such as low temperature steam distillation or reverse osmosis. This very much goes against a statement made by former Conservative MP Will Quince in the Wine Duty parliamentary debate on 05 March 2024, in which he stated that: “As a consequence [of climatic effects], there is very little that wine makers can do to lower the alcohol content.” The Exchequer Secretary rightly responded that cider is subject to seasonal variability too. A skilled wine producer – like brewers and cidermakers – will be very able to control the alcohol content of their product.

On the topic of cider, the WSTA rightly criticises the fact that cider is preferentially treated with a lower rate of alcohol duty than all other products in the strength band 3.5% to 8.4% (as the above charts show). This does indeed somewhat go against the public health objective of the duty system, especially when cheap, high-strength cider has been so harmful in this country. However, the way to fix this distortion would be to equalise cider rates with beer, not by introducing further distortions by preferentially treating wine with a permanent easement.

Are there really going to be 30 more tax bands?

Along with the chief executive of Majestic Wine and other wine producers, the WSTA has also claimed that once the easement ends there will be “30 different possible payments”. This is partly true as DEFRA now permits labelling to 0.1%, so wine producers can pay tax for each of the 30 tenths of a percent between 11.5% and 14.5% ABV. What they have rarely pointed out though, is that labelling to 0.1% is entirely voluntary and they can continue to pay tax for each 0.5% if they want to. On the occasion that they have mentioned it, the WSTA states that: “The introduction of taxation by degree will incentivise producers to label to one decimal point, this means that if the wine easement is removed, it is very likely to result in every business having to pay all 30 of the new per bottle amounts imposed by the new regime.” It isn’t clear why producers would label to 0.1%, particularly if importers explained that this would be more cumbersome. The only requirement for producers is to label their product to the nearest 0.5%. There is also an allowance of 0.5% in either direction to allow for production issues, so a bottle of 12.5% wine could actually be labelled as 12% or 13%. Alcohol taxation is a complex issue, needing accurate communication, and the WSTA appears to be trying to alarm and confuse its members, policymakers, and the public in this campaign.

A sensible and rational approach

The WSTA argues that the Treasury’s public health emphasis of the reform is “misleading” and the government is using public health as a “thin veneer to maintain market distortions”. Taxing wine by strength was a core part of the consultation submissions of public health groups. What the reform does, is (mostly) fixes the distortions that have been present for many years, and simply treats wine like other products. The 18-month easement was a generous policy that has temporarily maintained wine’s preferential treatment and duty distortion.

If cider rates were to be brought in line with beer rates, the reform would be an undeniably sensible and rational approach to taxing alcohol. The reform has been a well-researched and fully consulted on policy, and is now an example of good practice to other countries, with the World Health Organization highlighting the tiered system in a comprehensive tax manual (p.70) in 2023. It should be acknowledged as such.

Written by Jem Roberts, Senior External Affairs Manager, Institute of Alcohol Studies.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.

[i] BBPA Statistical Handbook 2023, Table B8.