It is sometimes suggested that alcohol control advocates, like the Institute of Alcohol Studies (IAS), are ‘neo-temperance’ campaigners. Because of the general perception of the temperance movement as glum, finger-wagging and judgemental, accusations of this type are not meant as a compliment.

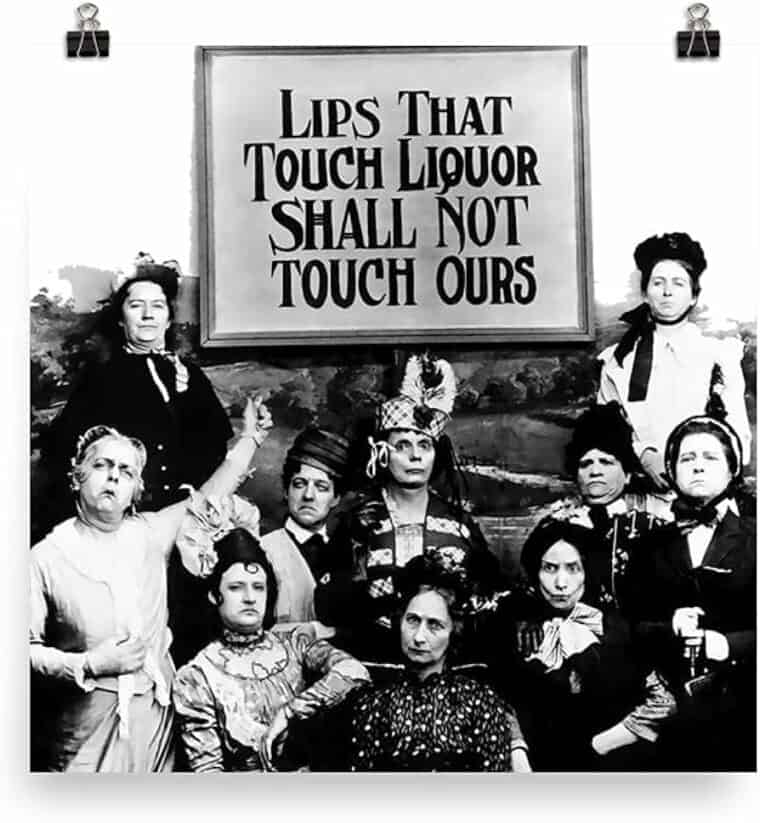

An example of anti-temperance satire from c. 1895

But are such accusations fair – either to alcohol control campaigners or their Victorian predecessors?

Historical connections

It is certainly true that the IAS has direct historical links with temperance. It was founded in 1983 by the United Kingdom Temperance Alliance (UKTA), which in 2003 changed its name to the Alliance House Foundation (AHF). The AHF remains the primary funder of IAS – something that is openly disclosed on the IAS website. The UKTA was itself was set up by the United Kingdom Alliance in 1942. Founded in Manchester in 1853, the United Kingdom Alliance was one of the most radical, and politically effective, temperance organisations operating in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was committed to promoting total abstinence through the total prohibition of alcohol, and came close to achieving its goal in 1892 when a Liberal Government, strongly influenced by Alliance activists, was elected promising (unsuccessfully in the end) to introduce prohibition legislation.

Other prominent alcohol control organisations also have direct links to temperance. Movendi International, previously known as IOGT, grew out of the Independent Order of Good Templars: an international temperance organisation that supported campaigns against alcohol in countries across the world. The AHF also played a key role in the establishment of the Global Alcohol Policy Alliance in 2000, about which its then Chairman commented ‘Only with the passage of time will we be able to assess the success of this venture, but I am delighted to say that so far it looks extremely promising.’

Not all alcohol control organisations have direct historical links to temperance. Some have very different historical roots. Alcohol Change UK, for example, was founded in 1982 (then as the Alcohol and Education Research Council) using unspent funds from a levy on brewers that had been created in 1904. Others have their background in treatment service delivery (e.g. Alcohol Concern – who later merged with Alcohol Research UK), or in medical bodies (such as Scottish Action on Alcohol Problems, which was created by the Medical Royal Colleges in Scotland in 2006).

Temperance beliefs

So, the claim that some alcohol control organisations have their roots in the temperance movement is true. But does this make them ‘neo-temperance’? Well, that depends on what you understand ‘temperance’ to mean…

The Victorian temperance movement is often stereotyped as joyless and puritanical – and there is no doubt some truth in this. A Times editorial from 1833 described early temperance campaigners as ‘pharisaical prigs’; Charles Dickens, writing in 1849 called total abstinence advocates ‘a public evil’. In 1859, the great Victorian liberal philosopher, John Stuart Mill, described prohibitionism as being based on a ‘monstrous theory’ of social rights which demanded everyone behave as temperance activists prefer.

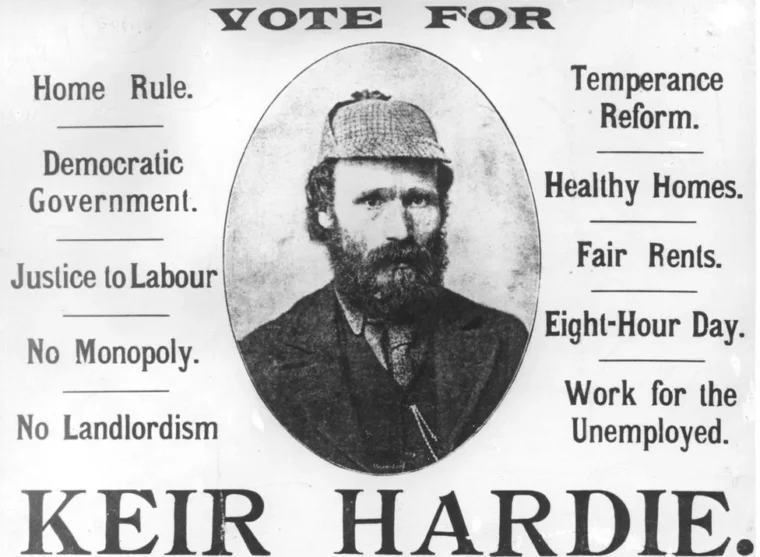

However, Victorian temperance was far more than this. Its view that alcohol was damaging to individuals and society was not only held by conservative moralists and utopian idealists (though there were plenty of those). It was also held by early anti-colonialists who, in Ireland for example, felt alcohol weakened the ability of colonised people to stand up for their freedom. Socialist temperance campaigners (including the founder of the Labour Party, Keir Hardie) believed the alcohol industry exploited workers by encouraging them to spend hard-earned money on the short-term escapism of drinking (money which, conveniently, funnelled back into the pockets of capitalist brewers…). The previously enslaved abolitionist Frederick Douglass noted that many plantation owners encouraged slaves to get drunk on occasion, as it created an illusion of freedom that did nothing to forward emancipation. Women rights campaigners (such as the tireless activist Frances Willard) called for temperance reform in order to reduce domestic violence.

Labour campaign poster from c. 1895

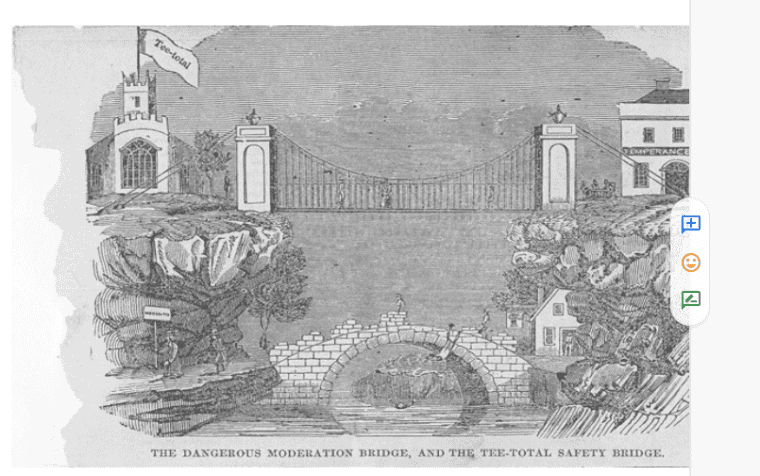

Temperance was, like the environmentalist movement today, a coalition of diverse and divergent groups. It was also, like many social movements, riven with internal disputes – especially between ‘moderationists’ (who supported action to reduce consumption) and total abstainers who, opposed as they were to any drinking, viewed moderates as mere servants of the alcohol industry. Abstainers themselves were split between those who supported reform through free, personal choice, and those (like the UKA) who believed the state should ban alcohol to protect people from themselves.

An anti-moderationist image (c. 1836)

The fall and rise of temperance

With the repeal of prohibition in America in 1933, and a long period of low alcohol consumption that ran from the outbreak of World War 1 until the early 1960s, temperance lost its social urgency and political edge. Many organisations closed down, others went into decline. However, increasing consumption and the emergence in the 1970s of a new ‘public health perspective’ on alcohol problems saw alcohol control re-emerge as a serious policy concern – and helped revive the population-level focus of political temperance. The temperance spirit, altered by time and focused more explicitly on health than moral virtue, began to re-emerge.

Recently, some alcohol control organisations have embraced their temperance roots. Others, by contrast, would doubtless balk at the comparison. The reality, though, is that many of the basic principles of temperance (that alcohol, because it can be harmful, should be subject to strict controls; that less drinking is better; and that no drinking might be best) are shared with contemporary alcohol control advocacy. Like temperance, contemporary alcohol control advocacy also encompasses a spectrum of views: ranging from the belief that all alcohol consumption is harmful and should be avoided, to a more liberal view that policy should constrain the exploitative tendencies of commercial actors while leaving individuals free to drink as they choose. And, as with temperance, these views can sometimes be in tension with one another.

If the term ‘neo-temperance’ is simply a way of calling campaigners nannies, then it is a crude oversimplification. However, if it points to the set of shared principles and policy positions, or asks questions about the underlying values motivating alcohol control advocacy, then it is not a complete misnomer. The question for contemporary alcohol control advocates, perhaps, is not whether they are inheritors of the temperance movement, but which version of temperance they most closely resemble.

Written by Dr James Nicholls, Senior Lecturer in Public Health, University of Stirling. He was previously Director of Research at Alcohol Change UK and Chief Executive Officer of Transform Drug Policy Foundation. He is author of The Politics of Alcohol: A History of the Drink Question in England.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.