Many people recognise the feeling. A night of drinking followed by regret. A sense you drank more than you meant to or that alcohol and a hangover has got in the way of work, relationships, or health goals. As we enter a new year, many of us may be thinking we consumed too much alcohol over the festive season, and new goals of lowering consumption may be motivated, at least in part, by reducing the negative feelings that alcohol causes.

We have a wealth of data that shows that people in treatment for alcohol use have experienced guilt and remorse over their drinking, particularly in qualitative studies highlighting certain subgroups, not least women and mothers. Probably because of the endless societal fascination with female ‘transgressions’.

But clinical subgroups aside, given alcohol is the UK’s most permissive drug, how common are feelings of guilt or remorse after drinking? And who experiences them most? We wanted to know this because it is plausible that if you experience these feelings, and experience them often, this may impact one’s sense of wellbeing, mental health and could even be a barrier to (or step towards) change.

Our new study, using data from the Alcohol Toolkit Study, focuses on adults who drink at increasing or higher-risk levels. It explores how prevalent feelings of guilt and remorse are, how frequently they occur, and which groups are most affected, raising important questions about stigma, help-seeking, and alcohol harm.

Why guilt matters

Guilt and remorse after drinking are often framed as personal emotions.

Guilt is about judging your own behaviour as wrong or unacceptable — for example, thinking “I shouldn’t have drunk” or “I’m bad for drinking”. Remorse adds regret about what has already happened, such as wishing you had drunk less or behaved differently.

People may feel guilt or remorse because they drink more than they intend to, because alcohol harms their health, or because they worry about the impact on others, work, or family life.

These feelings can shape behaviour in ways which are significant for public health. Research suggests guilt and remorse can stop people from seeking help, especially if they fear judgment from others or blame themselves for their drinking.

What we did

We analysed data from over 40,000 adults in England who drank at increasing or higher-risk levels. The data came from the Alcohol Toolkit Study, a large, nationally representative monthly survey.

Participants were asked whether, in the past six months, they had felt guilt or remorse after drinking — a standard question from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT).

We looked at how common these feelings were, how often they occurred, and how they differed by age, gender, social grade, and level of alcohol consumption.

One in eight people reported guilt or remorse

Overall, around one in eight people who drank at increasing or higher-risk levels said they had felt guilt or remorse after drinking in the past six months.

For most, these feelings were infrequent. Over 90% said they occurred less than once a month. Very few reported feeling guilty weekly or daily. This challenges the idea that guilt is constant or overwhelming for most people who drink at risky levels. But it also shows that these feelings are far from rare.

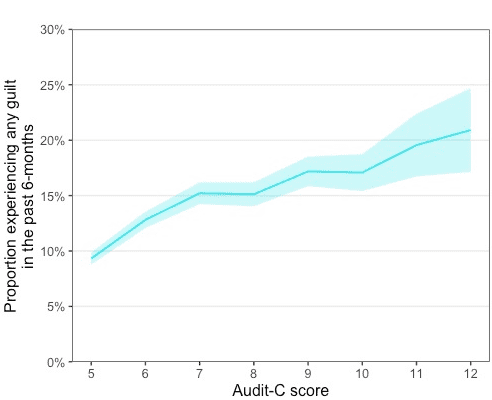

Guilt increases as drinking increases

Unsurprisingly, guilt and remorse became more common as alcohol consumption increased.

People drinking at the highest levels were more than twice as likely to report guilt compared with those at the lower end of the increasing-risk range. This is particularly concerning as people who drink more are the most likely to benefit from treatment and may not seek it if they feel guilty and remorseful. How we tackle this, especially among a backdrop of financial cuts to services, is a point for more discussion.

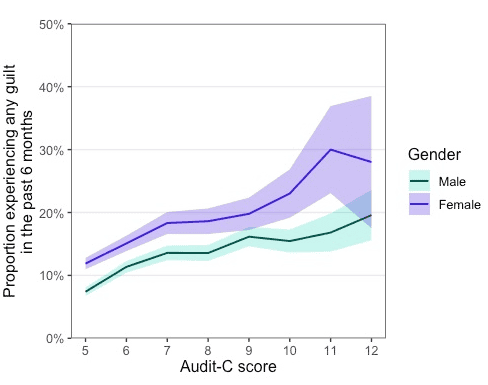

Women reported more guilt than men

One of the clearest findings was that women were more likely than men to report guilt or remorse after drinking — even after accounting for how much they drank and whether they had experienced alcohol-related harm.

This echoes previous qualitative research showing that women’s drinking is more heavily stigmatised, and that this stigma can be internalised, contributing to real-world evidence of stronger feelings of guilt and remorse.

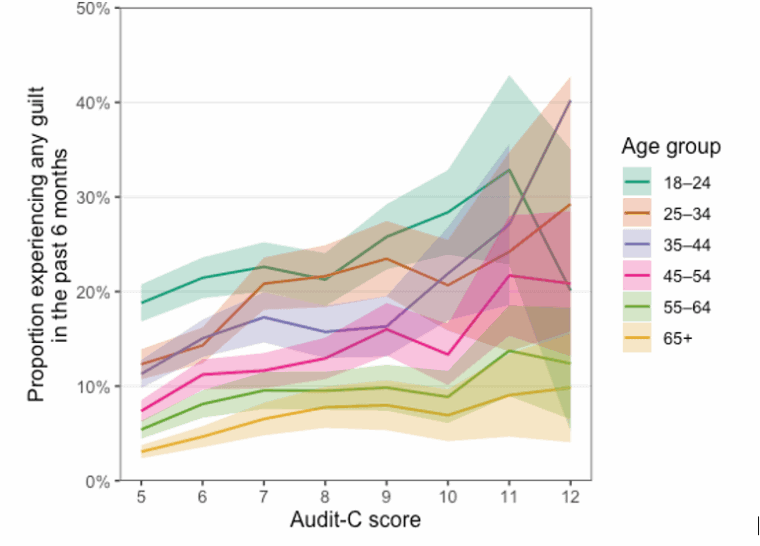

Younger adults felt guilt most often

Younger adults — especially those aged 18–24 — were the most likely to report guilt or remorse after drinking. Older adults were much less likely to do so.

Cohort effects may explain this. For example, changing attitudes with younger generations growing up with stronger messages about health, mental wellbeing, and “responsible” drinking. Older adults may generally be better at dealing with guilt and remorse based on longer-life experience and critical self-reflection may be less severe. More specifically, older adults may be accustomed to their drinking patterns, better able to manage negative feelings, or more likely to minimise harms if they have not experienced serious consequences of guilt.

More advantaged groups reported more guilt

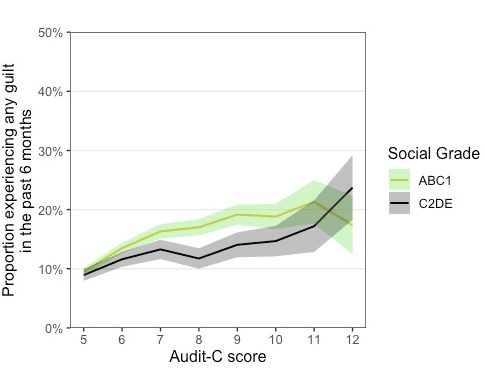

People from more advantaged social grades (this is defined in those in occupational grades ABC1 versus C2DE as per the National Readership Survey) were also more likely to report guilt and remorse than those from less advantaged groups.

This finding is complex. It may reflect differences in social expectations, awareness of health risks, or norms around “acceptable” drinking. It also reminds us that guilt is not a simple marker of harm — and that stigma can operate in uneven ways.

Epidemiological data like ours can tell us what people are feeling, but not why, so assigning meaning to these results is speculative.

Why this matters for policy and practice

Guilt can cut both ways. In some cases, it may motivate people to reflect on their drinking and make changes. But guilt can also tip into shame, a feeling linked to secrecy, avoidance, and disengagement, which may narrow social circles and preclude help-seeking.

A call for more compassionate support

Public health approaches to alcohol need to recognise these emotional dynamics. While there are ongoing debates about the role of stigma as a potential motivator or barrier to help-seeking, we show that certain subgroups require special attention. As alcohol-related harm continues to rise in England, understanding how people feel about their drinking and how this effects change is important.

You can read the full open-access paper in Drug and Alcohol Review here.

Written by Dr Sharon Cox, Principal Research Fellow, Department of Behavioural Science and Health, UCL.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.