Context: Changing drinking patterns during COVID

At the beginning of 2020, an unprecedented shock occurred: the COVID-19 pandemic. With pubs closed, daily life disrupted, and many people under severe stress, initial studies showed an increase in risky alcohol consumption in England.

This alarming rise in consumption was also reflected in the number of alcohol-specific deaths. In 2020 alone, this figure increased by 19% – the sharpest increase since records began in 2001 – and marked the start of a pattern that continued over the following years, raising concerns among health experts about lasting changes in drinking patterns. But where has the situation settled almost five years later? Has alcohol consumption returned to previous levels?

A new study, analysing monthly data from more than 200,000 adults across England, aimed to answer this question.

What this research examined

The Alcohol Toolkit Study has been surveying representative samples of adults monthly since 2014. This extensive data source has allowed us to track three key indicators: risky drinking, possible alcohol dependence, and mean weekly alcohol consumption.

To assess risky drinking and possible dependence, we used a tool called the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Consumption (AUDIT-C, from 0 for abstinence to 12 for dependence), where scores of 5 or higher indicate risky drinking and scores of 11 or above possible dependence.

To determine mean weekly alcohol consumption, we calculated the amount of alcohol, measured in UK units, that a person drinks in a typical week. One unit is equivalent to 10ml or 8g of pure alcohol, and one pint of higher-strength beer or a large glass of wine contains approximately three units.

The project analysed data from 2014 to 2024, thus enabling a direct comparison between the years before the pandemic and the years after.

It is also important to note that at the beginning of the pandemic a major change had to be made to the data collection method: the surveys were switched from face-to-face to telephone interviews. This change affected how people reported their alcohol use and required careful adjustment. It also complicates the interpretation of the study results.

What the study found

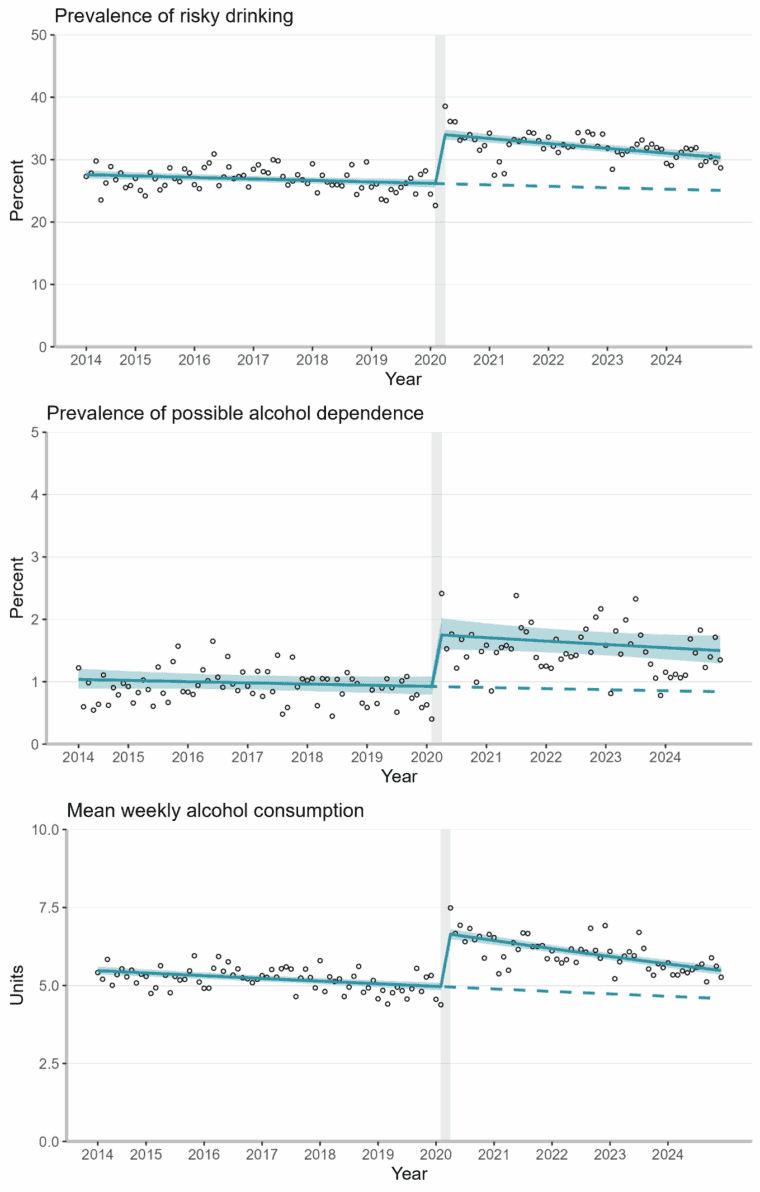

Immediately at the start of the pandemic, between February and April 2020, there was an abrupt rise across all three measures:

- Risky drinking increased by 30%.

- Signs of possible dependence nearly doubled, from 0.9% to 1.7%.

- Mean weekly alcohol consumption rose by 34%.

Even after trying to adjust for the changed data collection method, these increases persisted, though at a lower level, suggesting that the pandemic genuinely shifted drinking patterns.

Have we returned to pre-pandemic levels?

The short answer is: partly yes, but not uniformly.

Risky drinking and mean weekly consumption have begun trending back down. If current trends continue, projections suggest that England could return to pre-pandemic levels in the early 2030s. Adjusted models, which take into account the change in data collection method, suggest these levels may already be close to “normal” by 2025.

Possible dependence, however, shows no clear signs of returning to its pre-pandemic trajectory. This is particularly worrying because even slight increases in the percentage of people who are alcohol-dependent can have large impacts on the health system and premature deaths.

Not everyone is affected equally

The study revealed important differences between demographic and socioeconomic groups.

Women experienced greater increases in risky drinking and consumption than men at the start of the pandemic, although the levels have since declined more rapidly among women.

Risky drinking and consumption rose more sharply among people aged 30 and older than among younger adults (18-29 years) but also declined faster among them afterwards.

People from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds experienced a much greater increase in risky drinking and consumption, and crucially, their drinking patterns have not returned to pre-pandemic levels. In contrast, more affluent groups appear to be reverting to their previous consumption patterns.

This suggests that the pandemic may have deepened existing inequalities in alcohol consumption and its associated harms.

Looking beyond England: A quick snapshot across Great Britain

For the more recent period (2020–2024), the study also compared England, Scotland, and Wales. Scotland had the highest prevalence of risky drinking at the beginning of the period but has since seen a modest decline. Wales experienced a slight increase over time. England initially saw a rise followed by a decline, so that by the end of 2024 it had the lowest level of the three nations.

Patterns of possible dependence were relatively stable across all three, but weekly consumption decreased in England and Scotland but not in Wales.

What has happened in the meantime?

The years following the first phase of the pandemic have been turbulent. Rising living costs put households under pressure, accompanied by housing shortages and financial uncertainty. Evidence shows that economic stress can increase harmful alcohol use particularly among the most vulnerable populations.

This also appears to be happening now: Although national sales data suggest a recent drop in total alcohol purchases, the decline has not been uniform. The study results confirm this by showing that people in less advantaged groups have not reduced their drinking to the same extent as others.

Meanwhile, alcohol-specific deaths in England reached record highs in 2023 and remained elevated in 2024. This aligns with the study’s finding that dependent drinking has not returned to pre-pandemic levels.

Initial policy responses have followed, particularly in Scotland where the minimum price per unit of alcohol was raised from 50 to 65 pence at the end of 2024. England has not implemented a minimum unit pricing policy, but the government has increased funding for alcohol treatment services. Whether these current measures will be enough to reverse the trend triggered by the pandemic remains to be seen.

Why this research matters

Understanding changes in drinking over time is crucial for public health planning. Even modest increases in average consumption among population subgroups can lead to significant rises in alcohol-related harm, including cancers, liver disease, and premature death.

Two conclusions are particularly notable:

First, more people are drinking to levels indicative of alcohol dependence than before the pandemic.

Second, the increase in alcohol consumption among socioeconomically disadvantaged groups has not fallen back, threatening to worsen existing health inequalities.

The findings underscore the need for population-based interventions to address alcohol consumption. These include measures that target the affordability, availability, and marketing of alcohol. At the same time, access to treatment for people with alcohol dependence should be improved.

In summary

Ten years of data paint a nuanced picture of how drinking patterns in England have changed since the pandemic. A sharp spike in 2020 has gradually eased for many, with risky drinking and weekly consumption returning to previous trends. But not everyone is reverting to their pre-pandemic behaviour. Those with the highest alcohol consumption and socioeconomically disadvantaged people appear to be struggling most with the long-term effects of the pandemic on alcohol consumption.

As the country continues to recover from the pandemic and faces new economic challenges, understanding these patterns is crucial for public health, and studies like this help illuminate the path ahead.

You can read the full open-access paper in Addiction here.

Written by Dr Vera Buss, Senior Research Fellow, Department of Behavioural Science and Health, UCL, and Behavioural Research UK.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.