In mid-August, news emerged that the UK government is considering reducing the drink drive limit in England and Wales from 80mg of alcohol in 100ml of blood to 50mg*. This would bring them in line with Scotland, which reduced its limit in 2014, and with every other European country, all of which have limits of 50mg or less.

Drink drive collisions kill around 200-300 people in Great Britain every year, with thousands more left with life-changing injuries – a quick search of local papers finds stories of paralysis, brain damage, and amputations. Focusing only on deaths risks obscuring this wider devastation.

It points to the normalisation of alcohol use in the UK that so many of us tacitly accept people drinking a mind-altering substance before getting behind the wheel of the heaviest piece of machinery they likely operate. Most people wouldn’t use a circular saw after drinking two pints, or be happy with a surgeon operating on them after drinking, so why do we allow it with driving?

And progress has stalled. Drink drive deaths fell sharply in the 1980s and 90s, plateaued at about 230 a year from 2010, and have started creeping back up over the past three years.

The gap between confidence and reality

Although it may seem intuitively obvious that people shouldn’t drink and drive, there is a worrying gap between people’s confidence and reality. Research shows that at a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 70mg – within the legal limit in England and Wales – people rate their driving ability as the same as when sober, yet they have slower, less accurate reactions and weave in their lane. Even at 50mg, people are found to be significantly impaired.

The risks are well established. NICE’s 2010 evidence review found that drivers with a BAC of 20-50mg are at least three times more likely to die in a crash. Risk rises to six times at 50-80mg, and 11 times at 80-100mg.

Does lowering the limit work?

Yes – evidence from around the world shows reducing the limit saves lives. To list a few:

- A review of 15 European countries found reducing the limit from 80mg to 50mg reduced drink drive deaths by 11.5% among young people aged 18-25.

- In Australia, when the limit was reduced from 80mg to 50mg fatal accidents fell by 18% in Queensland and 8% in New South Wales. An increase in random breath testing was a major cause of this reduction, showing the importance of enforcement.

- And when Sweden adopted a 20mg limit in 1990, it reduced fatal crashes by 9.7%, with a 7.5% reduction in all crashes. Crucially, crashes also fell among the most serious drink-driving offenders.

But in the coming months, you’re much more likely to hear that it didn’t work in Scotland. The two main studies that found the limit didn’t reduce deaths or collisions highlighted some crucial issues with the policy – mainly that it wasn’t introduced alongside recommended policies that would ensure it works: increased enforcement, improved and cheaper access to public transport, and consistent public awareness campaigns. A recent poll found four in five people don’t know the current limit. To be effective, a lower limit must be backed by annual, engaging campaigns – free from alcohol industry influence – and visible enforcement.

Enforcement: the missing piece

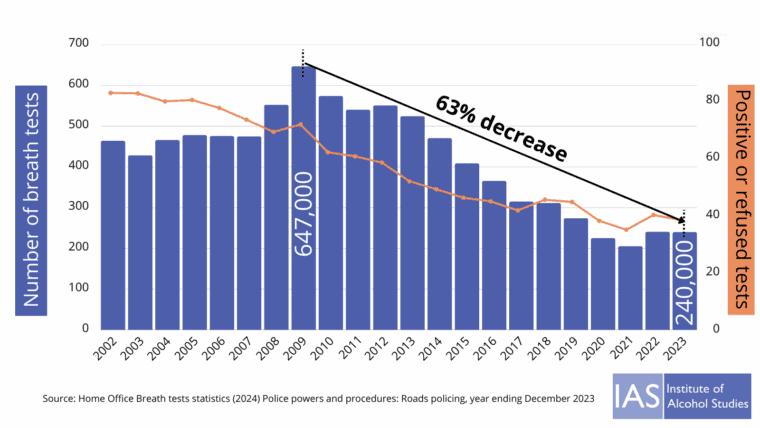

The main drink driving deterrent is people believing they may be stopped by the police and face serious penalties. Random roadside breath testing would provide the ideal complement to a lower drink drive limit. However, in recent years drink driving enforcement has collapsed, with the number of breath tests in England and Wales falling by 63% since 2009.

When the UK government previously rejected a lower limit in 2016, ministers argued resources should focus on “the most serious offenders”. Yet the drop in testing undermined deterrence across the board. If we are serious about tackling drink driving, lowering the limit must go hand in hand with visible enforcement.

Number of breath tests carried out by police in England and Wales, 2002 to 2023

Counterarguments – and why they don’t hold up

Lowering the drink drive limit has strong, broad support: public health groups, police, medical charities, many hospitality bosses, and 77% of the public all back it. Still, familiar objections will resurface. Here we offer counterarguments:

“Alcohol causes only 12–18% of road deaths – poor eyesight, speeding, and inexperience matter more.”

This is a classic distraction tactic. Yes, other factors like speeding and inexperience are major risks, but that doesn’t mean alcohol should be ignored. In fact, alcohol can exacerbate these risks, slowing reaction times, worsening vision, and making people more prone to speeding. The sensible response is obvious: “Let’s try and reduce ALL preventable dangers, alcohol included.”

“The UK already has some of the safest roads in the world.”

This statement is true and something to be proud of, however our roads are safer precisely because of sensible and thought-out policymaking: seatbelts, speed limits, breathalysers etc. The lesson isn’t to stop but to keep improving. Other countries with lower drink drive limits have seen greater reductions in deaths, and there’s no reason we shouldn’t aim higher too.

“It’s unfair on rural pubs.”

Some rural pubs may see a small decline in alcohol sales, as happened in Scotland from 2014 – but the impact was small and soon settled. Furthermore, as the Scottish Licensed Trade Association has stated, there are many bigger issues with the pub trade, and that if England and Wales reduce the limit: “There will be some impact, but going forward that should recover pretty quickly.”

Rural roads are among the most dangerous in the country, accounting for well over half of fatal collisions, far more per mile travelled than other roads. Protecting rural communities means reducing risk not turning a blind eye. Maintaining the status quo risks ALL rural pub visitors and staff – risks that many rural publicans would want to reduce.

We are also in quite a different environment to Scotland in 2014, another point highlighted by publicans. There are more alcohol-free options, young people are drinking less, taxis and ride-sharing options are far more available. As one argued: “Pubs need to be flexible and responsive to changing customer habits.”

“People who die from drink drive collisions are way in excess of the limits, so reducing the limit wouldn’t stop these people.”

Whilst this sounds convincing, it’s not backed up by evidence. Reducing the limit has been shown to significantly reduce drink drivers in fatal crashes at all BAC levels.

It also shows how important it is to have multiple drink drive counter measures – for instance the High Risk Offender Scheme, much better enforcement, and referrals to treatment for people who require help for their alcohol dependence. As part of a package of measures, lowering the limit is a proven policy to save lives.

Towards zero tolerance

As a publican recently stated: “In fact, a total ban would be easier to implement and understand.” And conversations around reducing the limit will beg the question: “Should the limit just be zero?” There would be no confusion then, no one incorrectly estimating how much they can drink before driving, and far lower alcohol-related risk. It would be a much easier message for the government to convey to people too.

Studies find that once people have started drinking, they are more likely to keep going, valuing another round over safety. This means that the assumption underpinning the current drink-drive limit – that people can sensibly weigh up risk after a couple of drinks – is flawed. A zero limit would better reflect how alcohol actually affects decision-making and reduce the likelihood of people convincing themselves they are “still okay to drive”.

The BMA has recommended a phased approach: first reduce the limit to 50mg, then to 20mg (effectively zero). Combined with tougher enforcement, improved awareness, and better treatment for high-risk offenders, this would bring England and Wales in line with best practice worldwide.

On its own, lowering the limit is not a silver bullet. But alongside stronger enforcement, public awareness, and identifying and supporting high-risk offenders better, it can finally restart progress after a decade of stagnation.

Written by Jem Roberts, Head of External Affairs, and Dr Katherine Severi, Chief Executive, Institute of Alcohol Studies.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.

*(or 35 micrograms of alcohol in 100 millilitres of breath down to 22 micrograms)