‘The shocking number of pubs that closed for good last year’ – The Independent

‘Pub closures to keep rising as ‘it’s impossible to make a profit’ – The Times

‘Last orders: Pubs in Britain will close at rate of one a day in 2025’ – The Guardian

We’re all very used to these headlines – and these were in 2025 alone. For decades now, there has been increasing concern at the decline in the number of pubs across the UK.

Yet most of these fatalistic articles hide a great deal of nuance about what has actually happened to the pub trade. To understand what’s really happening, we need to look at long-term trends, how ‘pubs’ are defined, who benefits from closures, and which policies actually matter.

Are pubs really all closing down?

Pubs have steadily been closing for well over 100 years. In 1904, there were almost 100,000 pubs in England and Wales. By 1950 there were 73,500, and now across the UK there are around 45,000.

Yet until the past few decades, there was far less of a public outcry, which has ramped up in the 21st century. How much we should care about this depends on the impact, from employment figures and economic growth to social cohesion and public health.

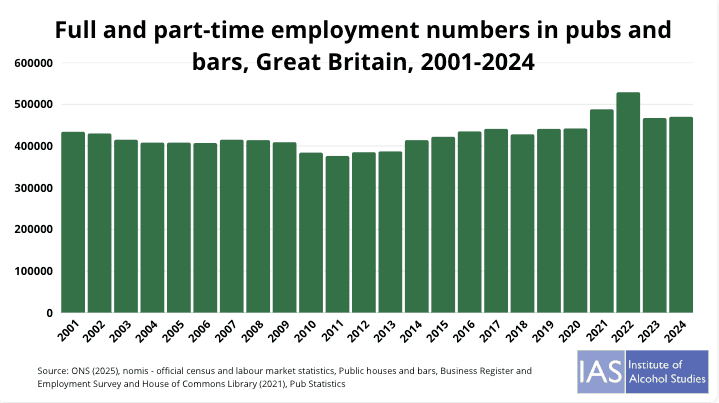

A frequent argument from trade groups, who typically argue for lower taxes and less regulation, is that declining pub numbers means job losses. Recent figures simply do not support that. While pub numbers have been falling, the number of people employed in pubs and bars has stayed very stable since 2001, and actually increased over the past decade.

What has changed is the size of pubs, with smaller premises closing and bigger premises opening, which employ more people. This explains why there has been a fall in the number of pubs but an increase in employment.

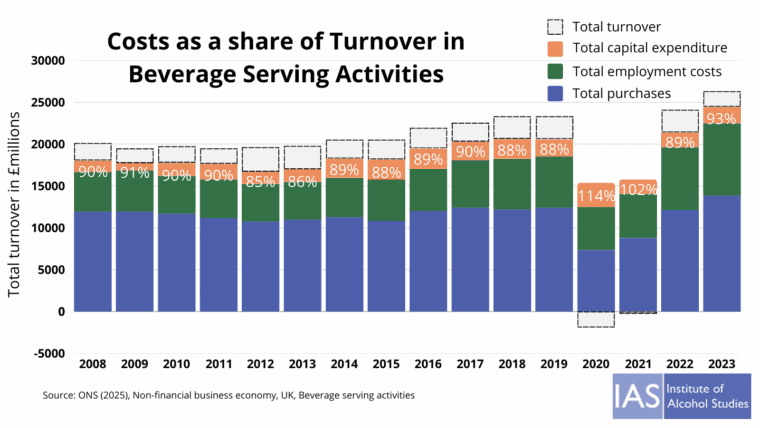

Despite reports of a struggling trade, data also show that turnover per establishment has increased since 2008. Of course, pubs may be less able to hold onto that turnover, if costs have risen substantially. It’s clear that the pandemic had a significant impact on turnover, severely costing the pub industry in 2020 and 2021. However, the decade before that was very stable, with costs accounting for 85-91% of total turnover. And it looks like there has been a post-pandemic recovery.

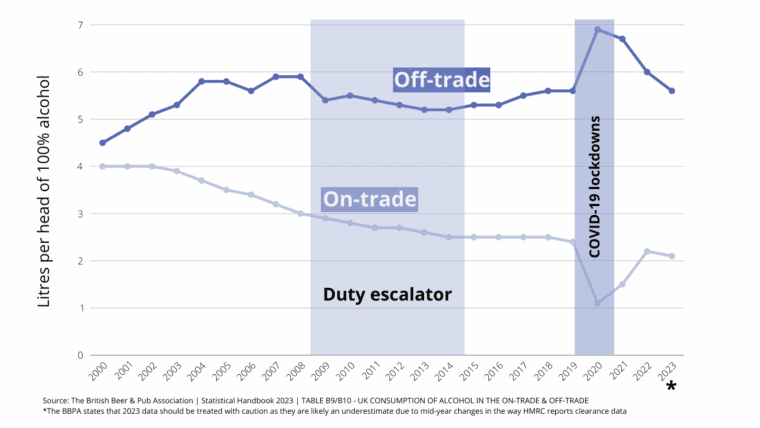

This growth in employment has been achieved while the UK has become a predominately home drinking nation. There has been a huge move away from pub drinking to drinking at home, partly driven by very cheap, supermarket alcohol. In the year 2000, people across the UK drank roughly the same amount in the on-trade as they did at home, which was already a huge shift from most drinking being in pubs in previous decades. And since 2000, the gap has widened dramatically, with three-quarters of drinking now being at home.

There are serious public health consequences to this. We know that higher risk drinkers account for 32% of alcohol-related revenue in the off-trade, compared with only 17% of revenue in the on-trade. This in turn has driven big increases in alcohol-related chronic diseases. Moving people back to drinking in a regulated environment, where measures cannot be overpoured, could have significant public health impacts. A 2012 study also found that, compared to high street bars and clubs, traditional pubs “engender more moderate drinking; diluting drinking with conversation, playing games, watching sports and so on”.

The ‘Great British Pub’: why definitions matter

The data suggests that there have been winners and losers in the pub sector over a very long period of time. But there are different kinds of pubs and, indeed, the definition of a pub matters for policy, regulation, and taxation, despite there being no clear definition of what a pub actually is.

This ambiguity is now colliding with live tax policy. The government’s apparent U-turn on planned business rates changes for pubs – but not other hospitality venues – has reopened a familiar question: what, exactly, qualifies as a pub for preferential treatment? Business rates apply to premises rather than drinking patterns or social function, leaving many venues stranded in the grey area between pubs, bars, restaurants, and hotels. Without a clear and principled basis for distinction, targeted relief risks either missing the pubs ministers claim to value, or extending support to a far wider range of licensed premises – regardless of the harms associated with them. For years, governments have claimed to be doing everything in their power to protect the ‘Great British Pub’, while simultaneously grappling with rising alcohol harm and introducing measures to address it. To do so the government needs to “distinguish pubs that might be identified with a ‘public good’ from other types of licensed premises more associated with ‘social ills’”.

George Orwell’s 1946 essay “The Moon Under Water” is often cited in characterisations of the ideal British pub, with its Victorian fittings, roaring fire, no noisy distractions that limit conversation, and simple, hearty food. This sounds close to the formula that has brought such success to the JD Wetherspoon chain – which actually has four pubs called the Moon Under Water in London alone – but Wetherspoon and similar chains are rarely mentioned in these discussions, perhaps because they don’t quite hit the right nostalgic chord.

We all have in our minds a picture of the pub that the government is trying to protect, but there’s little formal categorisation. CGA Strategy – an industry market research company that tracks pub figures – has previously said that it’s all very complicated… If a pub starts to sell food, it becomes a gastropub. If it sells even more food, it could turn into a restaurant. It hasn’t gone anywhere, it’s just no longer classed as ‘a pub’.

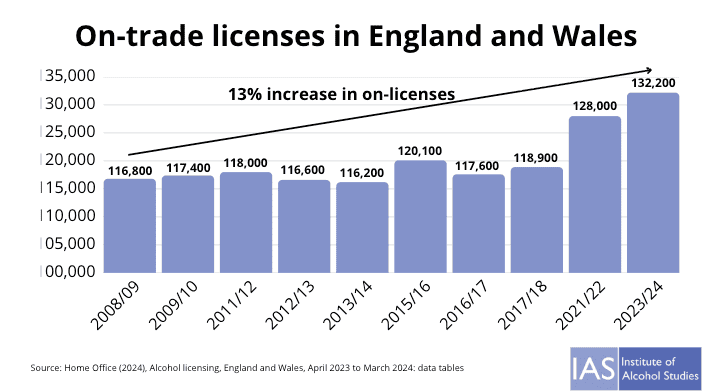

Incidentally this helps explain broader figures about the number of places licensed to sell alcohol on-premise, which have increased by 13% since 2008, driven by big increases in the number of restaurants.

If we define a traditional or community pub as a place “linking them to the culture surrounding them” and providing “a social hub for urban and rural communities…with opportunities to socialise, play games and even take part in transactions”, and often owned and run by members of the local community, there are many reasons to protect these establishments over high street bars, big chains owned by pubcos, and premises that sell off-trade alcohol.

Not only are there public health reasons to want to shift drinking from home back to pubs, there are also clear social and community benefits to good traditional pubs. They promote interaction between people from different backgrounds, host community-oriented events, often have in-house public services, and have clear cultural value, states an IPPR report. And the loss of them can “have a serious impact on the quality of local community life”. IPPR goes on to argue that these types of pubs are also responsible for very little social harm compared to other licensed premises, yet carry the same tax burden. A particularly detail-oriented economist would want to tax different premises different amounts, depending on the amount of alcohol harm – or ‘negative externalities’ – they cause.

In addition, alcohol sold in pubs is more valuable to the public purse that supermarket alcohol, as they employ more people than the off-trade. A pint sold in a pub raises twice as much tax as that sold through the off-trade (IPPR).

Is it just bad pubs that have disappeared?

The pubs that are closing, overwhelmingly, are those that existed to serve customers who came to drink and to smoke. Without the beguiling fug of tobacco smoke and the draw of cheap beer, such places find it much harder to survive.

So said the BBC’s Mark Easton in a 2009 article, and there’s a lot of truth to that.

One of the biggest shifts has been from ‘wet-led’ pubs to gastro (or food-led) pubs. This was happening throughout the second half of the 20th century, alongside a shift to attract more affluent crowds, young people, families, and women. A 1996 study spoke of how “pubs are now serving meals to an ever-increasing extent… Eighty-six percent of pubs now serve food”. At the same time, men were spending more time with their children, necessitating fewer old school boozers. The same study explains that there were “too many pubs”, with many being unprofitable or poorly managed.

There are far more positives that have come out of this shift away from the 1950s style of pub, which a 1988 Times article described as “indescribably filthy…with carpets greasy with chewing gum…[and] had a very smoky atmosphere”.

An older group of pub-goers were interviewed in 2023, capturing the simultaneous mix of relief that such pubs are evolving, and nostalgia for such places, their simple décor, basic facilities, smoky rooms, sticky floors, and old games like skittles, darts, and dominoes. They bemoaned the loss of “convivial drinking spaces” and food-led pubs not being ‘real’ pubs, partly attributing this change to gentrification. At the same time, they praised this change as being more welcoming, especially for older women. One interviewee said of male-dominated areas in old school pubs: “you was afraid of going into that bit”.

In another study, a young woman spoke of avoiding certain pubs because they were “rough”, saying she would “rather go and play on the motorway” than go into a particular pub near her.

So clearly it’s the case that many pubs that were just unwelcoming, unpleasant, or unprofitable have died or been replaced with something people actually want. A 2017 IAS survey of publicans backs this up, finding that a common perception was that pub closures were the result of poor management and a failure to respond to market trends.

Diversify or die

Not only has there been a clear shift to food-led pubs, but there have been other ways drinking establishments have diversified. With a rise in wine consumption and decline in beer, there has been a shift away from pubs towards bars. As Mark Easton noted 17 years ago, people may mourn the loss of “old-fashioned tobacco-stained drinking dens” but clearly the night-time economy was diversifying, with a more mixed option of cafes, bars, pubs, and restaurants. There are now far more varying options for people to choose from.

A director of a music production company told the BBC in 2025 that, since the pandemic, they’ve seen an increase in attendance at live music venues, but a decline in spending on alcohol. And a nightclub owner noted that young people are choosing to spend their money differently, saving for big events like festivals over nights out.

Much of this change is beyond the control of pub owners, but there are many that are taking change in their stride.

In rural areas, various strategies have been successful such as forming co-operatives, which requires community cohesion and investment, and more appealing environments attract families that otherwise wouldn’t visit.

Craft beer taprooms, more cafes serving alcohol, and beer festivals have also emerged.

And gentrification in many areas of the country has boosted and sustained pubs by attracting people with more disposable income. This has led to increases in microbreweries and gastropubs.

Existing regulars may “sob into their pewter pint mugs to see their local pub offering kids’ pumpkin carving come late October”, says the FT, but pubs have always evolved and have to continue to do so if they want to survive.

Recent research suggests that this diversification has coincided with growth in some parts of the pub trade. While overall pub numbers have fallen, pubs and bars in city centres, high streets, and student areas have expanded, driven mainly by larger, multi-site operators rather than independent locals.

Chains such as JD Wetherspoon illustrate how scale matters in a difficult trading environment. With hundreds of outlets, Wetherspoon is able to use its purchasing power to negotiate lower prices from suppliers, spread costs across its estate, invest in property, and keep prices low in a way that smaller, independent pubs simply cannot.

This mirrors the transformation seen in off-sales, where supermarkets used economies of scale to undercut independent retailers. Even where the number of licensed premises is stable or growing, ownership is becoming more concentrated.

Threats remain

Pubs have had to contend with very challenging circumstances over the years, from deindustrialisation to the pandemic.

The decline of heavy industry hit many pubs from the 1980s onwards. Pubs were the place where men would gather to recuperate after a day of physical work. The UK’s transition to a service-based economy changed how people drank. Old industrial towns and villages that surrounded pubs have totally changed, becoming commuter towns or second-home settlements, so understandably many of those pubs were forced to close.

The 2008 financial crash also had far-reaching implications, by reducing disposable incomes. This was unequally spread, areas with more people with university degrees and younger adult populations were more resilient.

And the pandemic had a varied impact on pubs too. There was a greater risk of closure in more deprived areas, peripheral towns, and for smaller businesses.

Alongside all of this, the growth in home-centred leisure has been an ongoing threat to the on-trade.

These big external shocks have made diversification and evolution all the more important.

What do publicans say?

There are a few common themes regarding what publicans say are the biggest threat to their pubs. Business rates and energy prices are commonly cited, as is competition from cheap supermarket alcohol. IAS’s 2017 survey found that cheap supermarket alcohol was also the biggest threat to their survival.

But it’s difficult assessing true threats because often the groups with the loudest voices that are quoted in newspapers aren’t quite the right people to listen to. Instead of hearing from real pub owners, articles often quote the BBPA or UKHospitality, both of which represent multinational brewers like Heineken and Molson Coors, or pubcos like Wetherspoon, Stonegate, Punch, and Greene King.

As Paul Crossman, Chair of the Campaign for Pubs, has stated:

Westminster politicians take entirely on face value the version of the industry presented to them by the best-resourced and best-placed lobbyists, which are of course those permanently on hand in the corridors of Westminster courtesy of funding provided by the largest players in the industry.

What you won’t hear from these corporate lobbyists is one of the biggest threats to pubs: pubcos.

Pubcos – or pub companies – are businesses that own multiple pubs. Ironically, considering the damage they’ve done to pubs, they arose in the 1990s after the government tried to reduce breweries’ hold on pubs. The aim was to break up an oligopoly, but while breweries were forced to sell pubs, no limit was set on how many any one buyer could own. Investment companies stepped in and bought thousands, simply shifting control from brewers to a new set of corporate landlords.

As with the previous predominantly brewery-owned system, pubcos often have highly restrictive contracts, including ‘beer ties’, which means the pubs are obliged to buy particular products. These are usually more expensive, meaning less profit for pubs or higher customer prices, and it means there’s no free market where pub owners can shop around for a broader range of different products and prices. It’s why so many pubs stock exactly the same draught beers.

As Crossman states:

In this case it is a failure by our policy-makers to perceive the fact we do not have a free and fair market in the UK beer and pub sector but instead have a complex cartel of powerful mostly offshore-owned brewing and pub-owning corporations that has gained an unhealthy dominance, and whose members collectively collude to defend their market turf from all outsiders.

Essentially pubcos turned pubs into financial assets from the 1990s. And a bit like the highly-leveraged, bundled mortgages that caused the 2008 financial crash, they grouped pubs into large, debt-backed financial products. This approach artificially supported thousands of pubs that weren’t commercially viable, so when the crash came, the system partly collapsed.

Without securitization, there would have been a ‘much steadier, consistent drip, drip of closures as pubs became unviable’, but yields attached to securitization artificially propped up thousands of pub businesses as part of interconnected financial chains. – Keenan, L. (2020). Journal of Economic Geography.

Pubcos also focused on pubs that were most profitable, which were typically larger, urban pubs, meaning smaller and more rural pubs were hit hardest.

Roger Protz, former editor of the Good Beer Guide, writing in 2014 highlighted the problem with this debt-backed approach:

Enterprise and Punch went on a wild buying spree in the early years of this century and then caught a terrible cold when the banking crisis caused a major economic crisis. In order to pay off some of their massive debts – and at one stage in 2014 the burden of debt almost sent Punch into administration – the big two have sold off swathes of perfectly viable and successful pubs. The pubs have become mini supermarkets, betting shops, fast food outlets and private housing. In some cases, the loss of a pub has ripped the heart out of a local community.

In 2016, the Pubs Code was introduced to try and address the imbalance between pubcos and tenants, and it helped a little, but many say it is still unfair.

As Crossman has explained, pubs are often going to be less profitable than other ways that real estate can be used, and with pubcos wanting to make money for shareholders, the community value of a pub is less important to them. As he states:

This fact, accompanied by the weak protection afforded to pubs in UK planning law, make them an easy target for unsuitable freeholders, whether corporate bodies or individuals, who see in them only the chance to turn a quick short-term profit.

This is why the Campaign for Pubs and Camra have repeatedly called for planning laws to specifically protect pubs. And the Localism Act 2011 did create the Assets of Community Value (ACV) scheme, which allowed communities to bid for pubs. However, this only really gave additional time for communities to do so, it didn’t prevent private sale, conversion, or demolition if planning rules allowed. Sometimes pubs are purposefully left to decay, so that they can be redeveloped with little pushback. Crossman argues that the only way to stop this is “far stricter planning protection where pubs are recognised as a special class of building with an inherent value that far exceeds their monetary price tag as a property”.

Solutions

Accepting that pubs are a safer drinking environment than the home, and that government policy should aim to shift home drinking back to pubs, there are a number of solutions that publicans, researchers, and the IPPR have laid out:

- Categorise traditional pubs differently from other drinking establishments (e.g. bars and clubs), in order to make licensing decisions and avoid over proliferation of riskier drinking premises (Roberts & Townshend, 2012).

- Treat pubs as a special community asset (Campaign for Pubs).

- Introduce much stricter planning laws to protect pubs from redevelopment (Campaign for Pubs).

- Support tenants to buy their pub (IPPR).

- End the beer tie to create a free market (Campaign for Pubs).

- Reduce the massive gap in on- and off-trade alcohol prices (Campaign for Pubs).

- Introduce minimum unit pricing to help close that gap and improve public health (IPPR).

- Introduce 50% business rate relief for “centres of community” (IPPR).

IPPR and others have also recommended that pub owners innovate in the sector and diversify more. For instance, setting up workspaces and using pubs as cultural venues and community hubs.

However, companies like Wetherspoon would likely be smart enough to work with these ideas to their advantage, again highlighting the importance of defining what it is that we want to protect in our communities.

From headline panic to policy reality

The decline in pubs has been somewhat overstated. The rise of gastropubs has meant that although pubs have fallen in number, employment has increased in recent years. Pubs have also become much more welcoming places over the past few decades.

However, there are clearly different risks to different establishments, and the ‘traditional pub’ is under threat in certain ways. If the government wants to support particular types of establishments, it needs to do a much better job at identifying the types it wants to protect and support, the specific problems facing those, and the specific solutions to those problems. This requires a nuanced understanding of the sector and well-crafted regulation that will achieve its aims and can adapt to changing circumstances.

A good first step would be to ignore corporate lobbyists whose aim is to increase the profitability of multinational brewers and pubcos, and instead listen to the people who actually run pubs: publicans.

Written by Jem Roberts, Head of External Affairs, and Dr Peter Rice, Chair, Institute of Alcohol Studies.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.