In this month’s alert

Editorial – April 2018

Welcome to the April 2018 edition of Alcohol Alert, the Institute of Alcohol Studies newsletter, covering the latest updates on UK alcohol policy matters.

This month, a new report has found that raising alcohol taxes by 10% could boost GDP by £850 million and create an additional 17,000 jobs in the UK. Other articles include: Drinking more than two units a day increases mortality risk; a Scottish study finds an association between higher crime rates and the number of alcohol outlets in a region; and a report reveals the lack of ‘joined-up action’ between alcohol and mental health treatment services.

Please click on the article titles to read them. We hope you enjoy this edition.

TOP STORY – Raising alcohol taxes could boost the economy

10% increase could boost UK GDP £850 million and jobs by 17,000

Dr Katerina Lisenkova |

11 April – A new report from the University of Strathclyde’s Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI), in conjunction with the Institute of Alcohol Studies, has found that raising alcohol taxes by 10% could boost GDP by £850 million and create an additional 17,000 jobs in the UK.

The economic impact of changes in alcohol consumption in the UK examines the net effect on the economy of a reduction in alcohol spending. Whereas previous analyses have looked only at the negative impact of lower spending on the alcohol industry, FAI’s study accounts for the likelihood that if people do not spend money on drinks, they will likely increase their spending on other products and services, and so other sectors will benefit.

Using a sector-by-sector model of the economy, incorporating the links between different industries and the wages and employment they generate, FAI model a range of scenarios associated with a 10% reduction in spending on alcohol in the UK – for example as a result of a successful government information campaign.

They find that the overall economic impact of reducing alcohol spending depends on what happens to the money that people would otherwise spend on alcohol. In one scenario, FAI assume that people chose to buy 10% less alcohol and to reallocate the saved money in proportion to the rest of their spending (so, for example, if on average people spend 20% of their income on housing, 20% of the money saved from alcohol would be redirected towards housing). In this scenario, GDP would slightly increase by £23 million, but employment would fall by 22,000 full-time equivalent jobs.

However, in practice, some goods and services are more likely to be substitutes for alcohol than others. To account for this, FAI model scenarios where all the money saved from alcohol is spent on grocery products (such as food, soft drinks, clothing), where it is spent on leisure (such as eating out, hotels, going to the cinema) and one in which it is spent on grocery and leisure.

In all three scenarios, GDP increases (by between £50 million and £350 million), while employment falls (by between 1,800 and 3,400 full-time equivalent jobs). This implies that a shift in preferences from alcohol to other products would result in fewer jobs overall, but that overall workers would be better paid.

However, one important exception is public services. FAI also look at the impact of a 10% increase in alcohol taxes, assuming that the proceeds are reinvested in public services. In this scenario, they find that both GDP and employment would rise. GDP would increase by £850 million, while 17,000 full-time equivalent jobs would be created. This authors therefore suggest that raising alcohol taxes could have a ‘double dividend’, stimulating the economy while reducing consumption and alcohol-related health harms.

Katerina Lisenkova, one of the authors of the report, said:

‘What our report shows is that policies to reduce alcohol consumption may not necessarily have a detrimental impact on the economy, even before considering any health or social gains. This is because when looking at changes in consumption patterns, people tend to shift spending from one area to another rather than not spend the money at all.’

Aveek Bhattacharya, Policy Analyst at the Institute of Alcohol Studies, added: ‘This important study challenges the argument that the government cannot afford to tackle cheap alcohol. While the weight of evidence that reducing the affordability of alcohol would save lives and reduce crime and violence should be reason enough to take action, this research strengthens the economic case for raising its price through taxation and minimum unit pricing.’

You can hear Katerina discuss the report in further detail on our Alcohol Alert podcast.

Drinking more than two units a day increases risk of death

Data support limits for alcohol consumption lower than current guidelines

14 April – Drinkers consuming more than the current UK guidelines of 14 units a week (two units a day) increase their risk of death, according to new research published in The Lancet.

In what is the most comprehensive study of its kind, a team of researchers led by Cambridge University’s Angela Wood reviewed data in 83 prospective studies from 19 countries involving a total of nearly 600,000 drinkers, all which contained a baseline measure of their drinking and a follow-up of their health outcomes at least a year later.

44% of participants were women, and 21% were current smokers. Unlike previous studies, the drinkers selected were relatively healthy, that is, without a history of cardiovascular disease at baseline. About half of the total study sample reported drinking more than 100 g of alcohol per week (12.5 UK units), and 8.4% drank more than 350 g (44 UK units) per week. Non-drinkers were also excluded from the study to minimise the possiblities of reverse causality (eg if ex-drinkers had abstained because of poor health) or unmeasured effect modification (ie if lifetime abstainers fundamentally differ from drinkers).

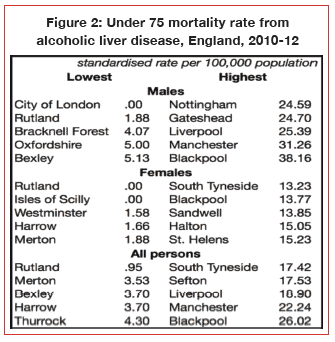

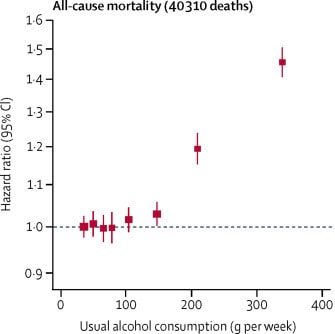

Researchers calculated a total of 40,317 deaths from all causes, (including 11,762 vascular and 15,150 neoplastic deaths), and 39,018 first incident cardiovascular disease outcomes, including 12,090 stroke events, 14,539 myocardial infarction events, 7,990 coronary disease events excluding myocardial infarction, 2,711 heart failure events, and 1,121 deaths from other cardiovascular diseases.

What did the research team find?

|

The chart above plots the risk of death associated with different levels of drinking, adjusted for a range of factors, including age, smoking status, occupational status, physical activity and general health. It shows little variation at lower levels of consumption, with lowest risk of dying around or below 100g (12.5 units) per week. However, above this level, the risk of death increases substantially, as a positive curvilinear association between alcohol and premature mortality.

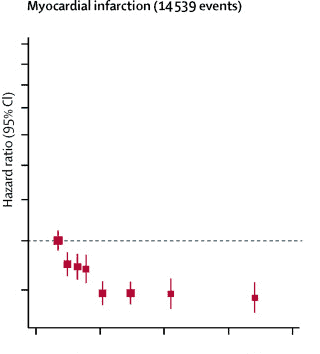

Comparing alcohol consumption with each cause of death yielded a more complex set of outcomes. Strokes, heart failure, and other types of cardiovascular disease saw similarly positive associations with alcohol, but coronary disease showed a less pronounced relationship, and the risk of myocardial infarction (heart attack) was inversely related to drinking up to 12.5 units of alcohol before flattening out (see below), a finding that supports UK Chief Medical Officers (CMOs) drinking guidelines suggesting that drinkers ought not to consume regularly more than 14 units per week, in order to keep health risks from drinking alcohol to a low level.

|

Wood and her colleagues estimated that overall, reductions in alcohol consumption could increase life expectancy by up to two years in a 40-year-old drinker, provided the reduction takes drinking down to the low-risk levels advised by the CMOs.

What about non-drinkers?

Speculating on the groups left out of the sample, the researchers wrote:

‘Former drinkers (n=29,726) and – to a lesser extent – never drinkers (n=53,851) had a higher risk of cardiovascular disease (and all-cause mortality) than even the heaviest drinkers in the sample.

‘However, the ex-drinkers and never drinkers probably represent quite different groups of people with distinct measured and unmeasured health characteristics. For example, compared with current drinkers, in never drinkers there was a higher proportion of women, non-white participants, people with poorer educational outcomes, and a higher prevalence of diabetes.’

Lessons to learn (and to avoid) from the study

Alcohol Policy UK editor James Morris remarked that the main concern for many in the alcohol field ‘remains how best to communicate drinking guidelines and associated risks‘, noting that ‘the real world complexity of alcohol harms and how drinkers take note of – or indeed dismiss – alcohol-related messages leaves many ongoing questions over how to make use of such evidence.’

This was anticipated by the authors of the study, who feared that their recommendations would be ‘described as implausible and impracticable by the alcohol industry and other opponents of public health warnings on alcohol.’

This prediction was proven right in the coverage of the story given by trade publication Drinks Business: ‘New study says drinking every day can take years off your life, and the drinks industry is furious‘.

In this article, representatives from cider and beer associations lamented the omission of the “well documented” mental health and social benefits of light-to-moderate drinking. James Calder, head of communications at the Society of Independent Brewers (SIBA) claimed that ‘the well known J-shaped relationship between alcohol consumption and mortality shows that with light to moderate consumption, your relative risk of total mortality drops significantly when compared to teetotallers.’

However, the lead authors of the study did stress that ‘the chief implication for scientific understanding is the strengthening of evidence that the association between alcohol consumption and total cardiovascular disease risk is actually comprised of several distinct and opposite dose–response curves rather than a single J-shaped association.’

Looking to the wider global implications of their work, they acknowledged that their meta-analysis was of studies that derived data from high-income nations, so further research would be necessary to investigate the stability of the findings in elsewhere in the world.

In his analysis of the reaction to the study, James Morris suggested that health groups may hope its findings would ‘help to move debate on from recurring questions over the exact recommended guideline towards what they hope may be a more suitable communication of the health risks given the still low level of awareness.’

Scotland: Higher crime rate linked to more drink outlets

Evidence strengthens association found from previous report

|

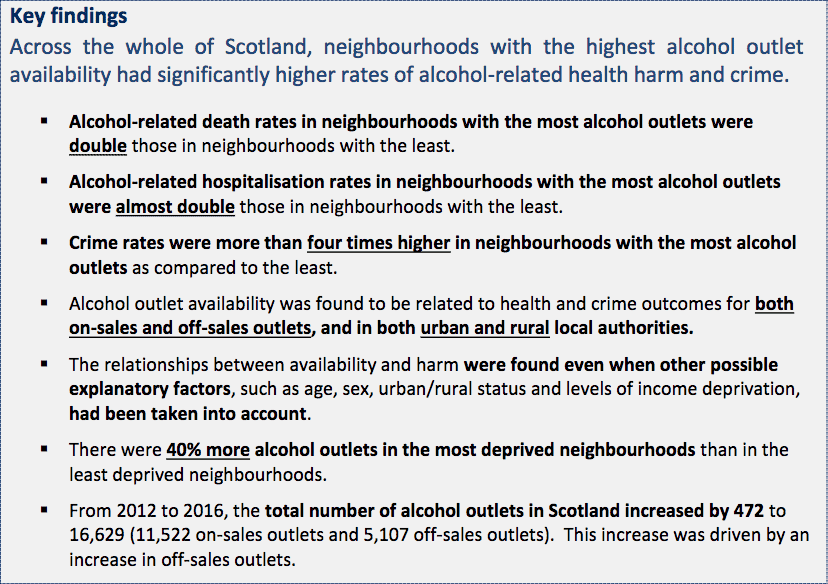

19 April – Crime rates are almost eight times higher in areas with the most alcohol outlets compared with the least, a new study has revealed.

Researchers also found that death rates were up to five times higher in parts of Scotland where drink was most easily accessible.

The study – carried out by Alcohol Focus Scotland (AFS) with academics from the Centre for Research on Environment, Society and Health (CRESH) – also discovered that there were 40% more pubs and off licences in the most deprived neighbourhoods than in the wealthiest areas of the country.

Alcohol Outlet Availability and Harm in Scotland bolsters previous research carried out by CRESH in 2014, which found a positive relationship between alcohol availability and harm across Scotland. It also comes as Holyrood’s Health Committee this week unanimously backed a 50p minimum unit price for alcohol, ahead of its introduction on 1 May 2018.

Information was gathered on the number of places selling alcohol, health harms and crime rates within neighbourhoods across the whole of Scotland and for each local authority area. Researchers then compared data zones (small areas representing neighbourhoods that have between 500 and 1,000 residents) to see if there was a relationship between the number of alcohol outlets in a neighbourhood and the rates of alcohol-related deaths and hospitalisations, as well as between alcohol outlet availability and crime and deprivation rates.

On the crime factor, the study revealed on average that crime rates were more than four times higher in neighbourhoods with the most alcohol outlets compared to those with the least. But the rate peaked at almost eight times higher in Aberdeen, South Ayrshire and Moray.

Other key findings were:

Speaking on the research, AFS Chief Executive Alison Douglas welcomed the “extremely useful evidence”, adding: ‘These are significant crimes and the association is striking.

‘It shows that there is a very strong link between a range of harms and levels of availability across communities in Scotland.

‘These crimes have considerable impact on communities and the association is all the more striking given the data does not include things like drink driving, breach of the peace and anti-social behaviour, which may be more commonly thought to be associated with alcohol consumption.’

She said the new study should be used to help inform the Scottish government’s next steps on alcohol prevention which are due to be published this summer.

Ms Douglas added: ‘The implementation of minimum unit pricing will save the lives of hundreds of Scots, but if we are to truly turn the tide of our alcohol problem tackling availability must also be part of the mix.’

Support for kids of alcohol-dependent parents confirmed

Help arrives in the form of a £6m package of measures

23 April – The UK Government has pledged to increase support for children with alcohol-dependent parents. Plans include a faster identification of at-risk children and the appointment of a dedicated minister with specific responsibility for the estimated 200,000 children with alcohol-dependent parents living in England.

This package of measures is backed by £6 million in joint funding from the Department of Health and Social Care and the Department for Work and Pensions, which comprises a £4.5m ‘innovation fund’ for local authorities to improve outcomes for the children affected, plus £1m for ‘national capacity building’ by non-governmental organisations. Local authorities will be invited to bid for funding by coming up with innovative solutions based on local need, with priority given to areas where more children are affected.

Public Health Minister Steve Brine, who was chosen as the dedicated minister for children with alcohol-dependent parents, made the statement:

‘All children deserve to feel safe – and it is cruel reality that those growing up with alcoholic parents are robbed of this basic need.

‘Exposure to their parent’s harmful drinking leaves children vulnerable to a host of problems both in childhood and later in life – and it is right that we put a stop to it once and for all.

‘I look forward to working with local authorities and charities to strengthen the services that make a real difference to young people and their families.’

Health and Social Care Secretary Jeremy Hunt said:

‘The consequences of alcohol abuse are devastating for those in the grip of an addiction – but for too long, the children of alcoholic parents have been the silent victims. This is not right, nor fair.

‘The measures will ensure thousands of children affected by their parent’s alcohol dependency have access to the support they need and deserve.

Hunt also paid tribute to his Labour Party counterpart, Jon Ashworth MP, who campaigned for the changes on behalf of charity The National Association for Children of Alcoholics (NACOA), adding:

‘Some things matter much more than politics, and I have been moved by my Labour counterpart Jon Ashworth’s bravery in speaking out so honestly about life as the child of an alcoholic. I pay tribute to him and MPs with similar experiences across the House [of Commons] who have campaigned so tenaciously to turn their personal heartache into a lifeline for children in similar circumstances today.’

Brexit must ‘Do No Harm’ to public health

Amendment raised during Withdrawal Bill debate in Lords

23 April – The UK Government has promised that it will continue to protect the public health of its citizens as the country leaves the European Union (EU).

The issue was raised by Lord Warner as peers debated the EU Withdrawal Bill in the House of Lords main chamber. The issue came as an open letter from Faculty of Public Health president John Middleton and 39 other organisations called on the government to preserve a clear legal safeguard on the nation’s public health.

Warner tabled the following amendment:

17A: After Clause 5, insert the following new Clause—“Public health protection

Article 168 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, so far as it requires a Minister of the Crown or a public authority to have regard to the principle that a high level of human health protection must be ensured in the definition and implementation of all policies and activities, forms part of retained EU law.”

The clause sought assurances that the EU Withdrawal Bill would retain Article 168 in British law, as the legal advice Lord Warner had been given by three professors of European law at the Universities of Sheffield, Essex and Cambridge was that it is ‘not clear’ whether it did. He raised concerns that the government had so far been ‘unwilling’ to confirm or deny their position, simply asserting that ‘the amendment is unnecessary because our public health policies are excellent and often better than many in the EU.’

Moreover, the crossbench peer referenced the fact that more than 50 organisations – including the Royal College of Physicians, the Faculty of Public Health and many major charities such as Cancer UK, Diabetes UK and the Alzheimer’s Society – backed the amendment because they were worried ‘hard-won legal protections for public health will be sacrificed in a rush to do trade deals’.

Responding on behalf of the government, Lord Duncan of Springbank accepted that ministers had ‘not thus far provided sufficient assurance… on the issue of public health’. However, he then went on to explain that ‘the elements of this and other cases which refer to the key role of public health are, to the extent that they are relevant to EU law, preserved by Clause 6(3)’ and that ‘the effect of Article 168 in the domestic law of this country before exit will continue after exit by virtue of Clause 4’, Lord Duncan said that he hoped that this analysis would allay fears among members of the upper house that the adequate legal safeguards were already in place.

The debate ended harmoniously; Lord Duncan promised that the issue would revisited during the bill’s Third Reading, and Lord Warner closed proceedings remarking that he was satisfied enough by Lord Duncan’s interventions to withdraw the amendment.

One-in-ten PMS cases linked to drink

Association found, causality unknown

24 April – The first meta-analysis of studies examining the link between premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and alcohol consumption has found a positive correlation.

Published in BMJ Open, researchers trawled data from 19 studies in eight countries featuring nearly 50,000 participants, uncovering a ‘moderate association’ between drinking and premenstrual syndrome (PMS) symptoms such as cramps, breast tenderness, fatigue, moodiness, and depression – intake was associated with a 45% increase in risk.

The link was more pronounced with heavy drinkers, at 79%, equivalent to one average-sized drink per day or more, suggesting that drinking may be the cause rather than the consequence of some PMS cases.

But the data ‘cannot strictly rule out that PMS causes women to drink in order to mitigate their symptoms,’ study co-author Bahi Takkouche of the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain told the news agency AFP.

Still, the study authors believe that the high number and the consistency of the links revealed by studies looking at the relationship between both factors suggest that alcohol is the likely probable cause.

The team wrote:

‘Worldwide, the proportion of current female drinkers is 28.9%, while that of heavy female drinkers is 5.7%. In Europe and America these figures are much higher and reach 59.9% for current drinking and 12.6% for heavy drinking in Europe.

‘Based on the figures above and on our results we estimate that 11% of the PMS cases may be associated to alcohol intake worldwide and 21% in Europe.’

Either way, the findings ‘are important given that the worldwide prevalence of alcohol drinking among women is not negligible’.

Bill should cover drunken sexual assault of emergency workers

Open letter as seen in The Guardian

25 April – As leading health bodies and members of the Alcohol Health Alliance UK, we write in support of Chris Bryant’s private member’s bill on assaults on emergency workers, and specifically his amendment to extend this bill to cover sexual assault. The bill will already make offences, including malicious wounding and grievous or actual bodily harm, aggravated when perpetrated against emergency workers. But it does not offer any additional protection against sexual assault. This is a discrepancy that cannot stand.

Research from the Institute of Alcohol Studies shows that between a third and a half of service people have experienced sexual harassment or abuse at the hands of intoxicated members of the public: over half (52%) of ambulance service workers reported that they had been the victim of intoxicated sexual harassment or assault, as did 41% of police staff, 35% of emergency department consultants and 34% of fire and rescue staff.

The evidence and shocking case studies from emergency workers across different professions make the case for including sexual assault in this bill. We cannot be in a situation where physically assaulting an emergency worker is recognised in law as being serious, but sexually assaulting them is not. We understand the government is resisting this amendment on the grounds of not wanting to create “two tiers of victims” of sexual assault. However, the bill does not give new or enhanced rights to emergency workers who are assaulted; instead, it offers protection to those people who – through their jobs serving our communities – are put at significantly greater risk of being sexually or physically assaulted. It recognises that these workers would not be in the position of being assaulted were it not for their jobs – so it is right that we make assaulting these workers an aggravating factor when cases are prosecuted. It will send a strong message to emergency workers that we stand by them, and to would-be perpetrators that these attacks will not be tolerated.

The bill, which will improve working conditions for frontline workers in emergency services, has been subject to a high degree of cross-party support, and we appreciate the support the government has shown. We now ask the government to reconsider its opposition to including sexual assault, and to support Mr Bryant’s amendment on Friday.

Please click through to The Guardian website to view the full list of signatories.

Alcohol and mental health services ‘lack joined-up action’

Report exposes ‘poor’ levels of service support for sufferers of both conditions

26 April – The UK Government’s next alcohol and mental health strategies must address the needs of users with co-occurring conditions. This is the central message of service providers from both sectors following a seminar which discussed the findings of a new survey looking into current provision standards and the barriers to effective help.

Produced by the Institute of Alcohol Studies and Centre for Mental Health, the report Alcohol and Mental Health: Policy and practice in England found that the treatment systems of both the alcohol and mental health sectors fail to regard each other’s existence, even when identified by patients and service providers. More than two-thirds of respondents felt that support for people with co-occurring conditions was ‘poor’.

It also found that trust and understanding between alcohol and mental health services were weak, largely due to barriers to greater integration including funding and workforce shortages (especially in alcohol services through lack of training), and the stigma facing people with co-occurring conditions – more than 90% of survey respondents viewed funding shortages as a problem.

A particular area of concern among respondents was the accessibility and quality of care offered to homeless people, with three-fifths (61%) of respondents suggesting they receive worse than average access to services and almost half of them (46%) suggesting they receive a worse than average standard of service.

Service workers from both fields attending the seminar supported the finding, believing that such an issue would require a particular effort from central government to identify and implement the necessary solutions on a national scale.

|

Homeless people are most likely to have worse than average access to or standard of treatment in mental health services |

Treatment service staff in either sector were likely to be critical of their own services’ levels of support for users with co-occurring conditions. Alcohol service staff were, however, overall more critical of mental health services than vice versa – only 7% of alcohol workers thought alcohol was adequately considered in mental health services compared with 45% of mental health staff.

The report calls for concerted national leadership to improve the support offered to people with alcohol and mental health problems.

It recommends the UK Government should develop a comprehensive alcohol strategy for England that will include action to ensure more people get effective, joined-up help, while prioritising help for people with co-occurring alcohol problems in the next Five Year Forward View for Mental Health.

Commenting on the findings, Lord Brooke of Alverthorpe, who chaired the seminar, notes: ‘It is clear from this report that not only is it common for those suffering from alcohol use disorders to also experience mental health difficulties, but that these people are being left behind. Government should act on this now – this situation cannot continue. A new Alcohol Strategy and a second Five Year Forward View for Mental Health that consider this co-morbidity are urgently needed.’

Centre for Mental Health Chief Executive Sarah Hughes said: ‘The links between poor mental health and alcohol misuse are clear and well known. Yet people facing difficulties with both still get little effective help in many parts of the country. Severe financial constraints on local authorities in particular are clearly part of the picture. But our survey also shows that poor communication and a lack of trust between alcohol and mental health services are longstanding barriers to better support. And for many very vulnerable people the result is poor access to effective help when they most need it.

‘We hope that the government will provide much-needed national leadership by setting a clear direction of travel for both alcohol and mental health support and by addressing gaps in funding for local authorities.’

Institute of Alcohol Studies Chief Executive Katherine Brown said: ‘Our report shines a light on what professionals in both alcohol and mental health service sectors have known for some time – but the problems of joint service provision have rarely been acknowledged outside both fields until now.

‘We hope that bringing such issues out into the public domain will spark a debate in which the views of workers and service users will contribute to the forging and implementation of more holistic public health strategies. Government acknowledging this through a new Alcohol Strategy and a second Five Year Forward View for Mental Health will be central to achieving this.’

Could lower strength drinks raise consumption levels?

Study questions policymakers’ legislative wisdom

27 April – Wines and beers labelled as lower in alcohol strength may increase the total amount of alcoholic drink consumed, according to a study published in the journal Health Psychology, funded by the Department of Health and carried out by the Behaviour and Health Research Unit at the University of Cambridge in collaboration with the Centre for Addictive Behaviours Research at London South Bank University.

Their randomised controlled trial of 264 weekly wine and beer drinkers into three taste-testing groups showed that the total amount of drink consumed increased as the label on the drink denoted successively lower alcohol strength.

In one group participants taste-tested drinks labelled ‘Super Low’ and ‘4%ABV’ for wine or ‘1%ABV’ for beer. In another group the drinks were labelled ‘Low’ and ‘8%ABV’ for wine or ‘3%ABV’ for beer. In the final group participants taste-tested drinks labelled with no verbal descriptors of strength, but displaying the average strength on the market – wine (‘12.9%ABV’) or beer (‘4.2%ABV’).

The mean consumption of drinks labelled ‘Super Low’ was 214ml, compared with 177ml for regular (unlabelled) drinks. Neither individual differences in drinking patterns nor socio-demographic indicators affected the results.

Dr Milica Vasiljevic |

The central issue of the study’s findings was expressed by the researchers – that the increased presence of lower strength alcohol drinks may result in more people drinking, but that it is not yet known if this effect is sufficient to result in the consumption of more units of alcohol overall.

This problem was framed by University of Cambridge academic Dr Milica Vasiljevic (pictured), who asked:

‘For lower strength alcohol products to reduce consumption, consumers will need to select them in place of equal volumes of higher strength products. But what if the lower strength products enable people to feel they can consume more?’

Yet in the UK, policymakers are currently holding a consultation over the possibility of adopting industry friendly legislative changes as part of a range of steps to reduce overall alcohol consumption, including the extension of the variety of terms that could be used to denote lower alcohol content and of the strength limit to include products lower than the current average on the market (12.9%ABV for wine and 4.2%ABV for beer).

The team of researchers also noted that the participants of their study were tested in carefully curated settings (a bar-laboratory), and that research in real-world settings is needed in order to learn more about the impact of lower strength alcohol labelling.

ALCOHOL SNAPSHOT: Rich face the brunt of alcohol policies in most countries

|

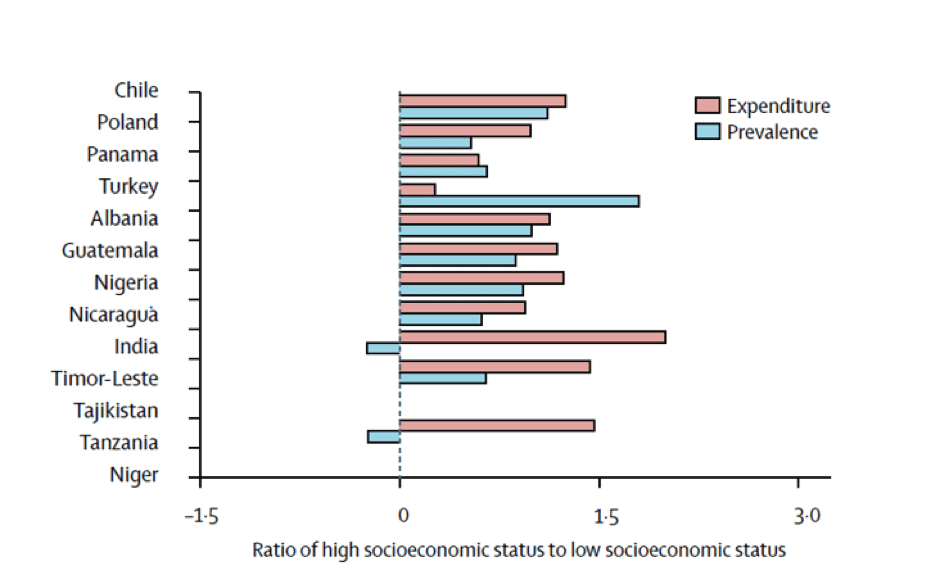

One of the most common objections to tax and pricing policies to reduce harmful alcohol consumption is the fear that they will disproportionately hurt the poor, who will be unable to bear price increases. That’s the argument addressed by a team of economists led by Franco Sassi of Imperial College in an article published in The Lancet last month, entitled Equity impacts of price policies to promote health behaviours.

In the paper, Sassi et al collate survey data from several countries to produce the chart above comparing the rich and poor in terms of their consumption of alcohol, and the amount they spend on it. Despite looking at a diverse set of countries from different continents, and of different income levels, the results are remarkably consistent. The blue bars show the ratio of prevalence of alcohol consumption in the top 20% richest households to the bottom 20% poorest households. In almost every country, richer households are more likely to drink, with India and Tanzania the only exceptions. For example, in Turkey, the top quintile is twice as likely to drink as the bottom. The red bars show the ratio of expenditure on alcohol between the richest and poorest quintiles. Here, the picture is even clearer: in every country, the rich spend more. Notably, India and Tanzania have the largest disparity, indicating that in these countries, even though the rich are less likely to drink, those that do drink spend far more on alcohol.

Sassi et al conclude that evaluating the impact of pricing policies is highly complicated, depending on a number of factors, including which products the measure targets, whether we consider only drinkers or include non-drinkers in our analysis and whether health benefits are factored in. However, this analysis, at least, suggests that richer households bear more of the burden.

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

Gambling industry harms and parallels with the alcohol world

Will Prochaska –

Coalition to End Gambling Ads