In this month’s alert

Alcohol and the Heart: Explained

Which cardiovascular diseases does alcohol cause? How many hospital admissions does it lead to? Why do observational studies suggest moderate drinking is good for the heart? And how has the alcohol industry tried to influence research on the topic?

Watch our latest Explained film – Alcohol and the Heart: Explained – to find out. Professor Annie Britton was our expert speaker in the film.

Professor Tim Stockwell, the former Director of the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, presented on the same topic at a public lecture in Edinburgh on 17 April. At the talk, which was co-hosted by IAS, SHAAP, and the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, Professor Stockwell explained the many confounders that skew the results of observational studies and lead to the infamous ‘J-shaped curve’. You can catch up on his lecture here.

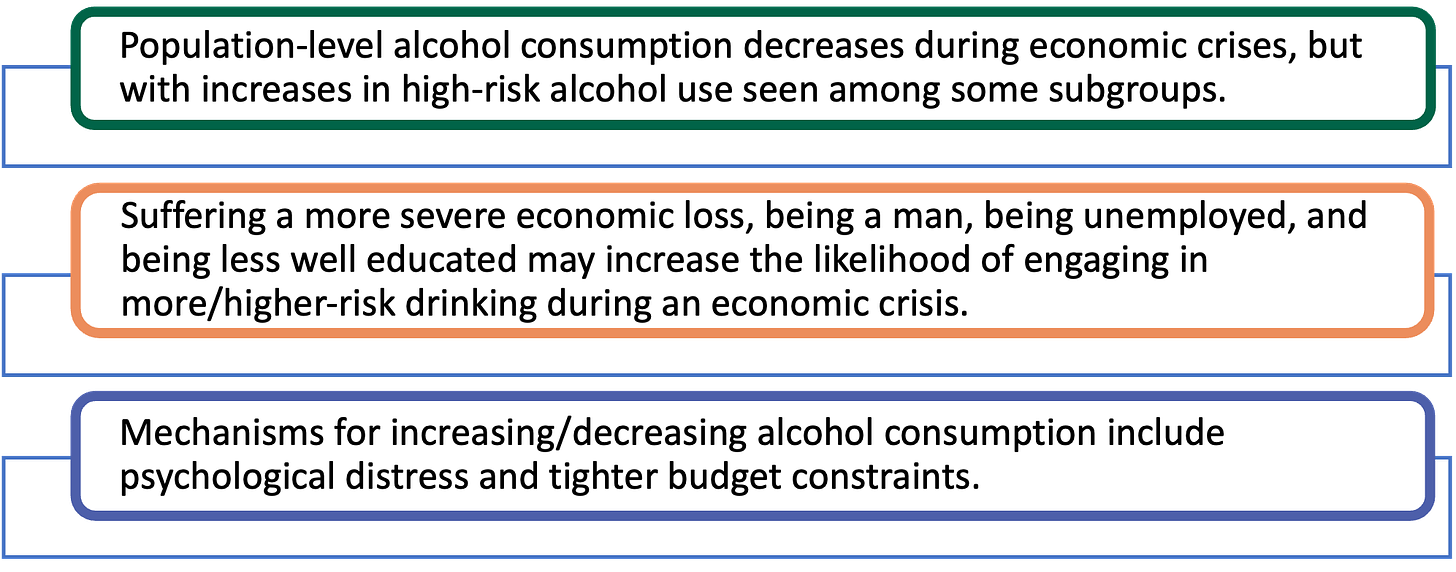

What happens to alcohol consumption and harm during economic crises?

Our latest briefing looks at times of economic turmoil – such as the 2008 Recession and the Covid cost of living crisis – to understand how such crises affect population-level alcohol consumption.

Our findings suggest that:

We suggest a number of strategies to reduce or prevent increases in alcohol harm during cost-of-living crises, including targeted support for people experiencing unemployment, and population-wide measures to improve access to treatment and reduce consumption.

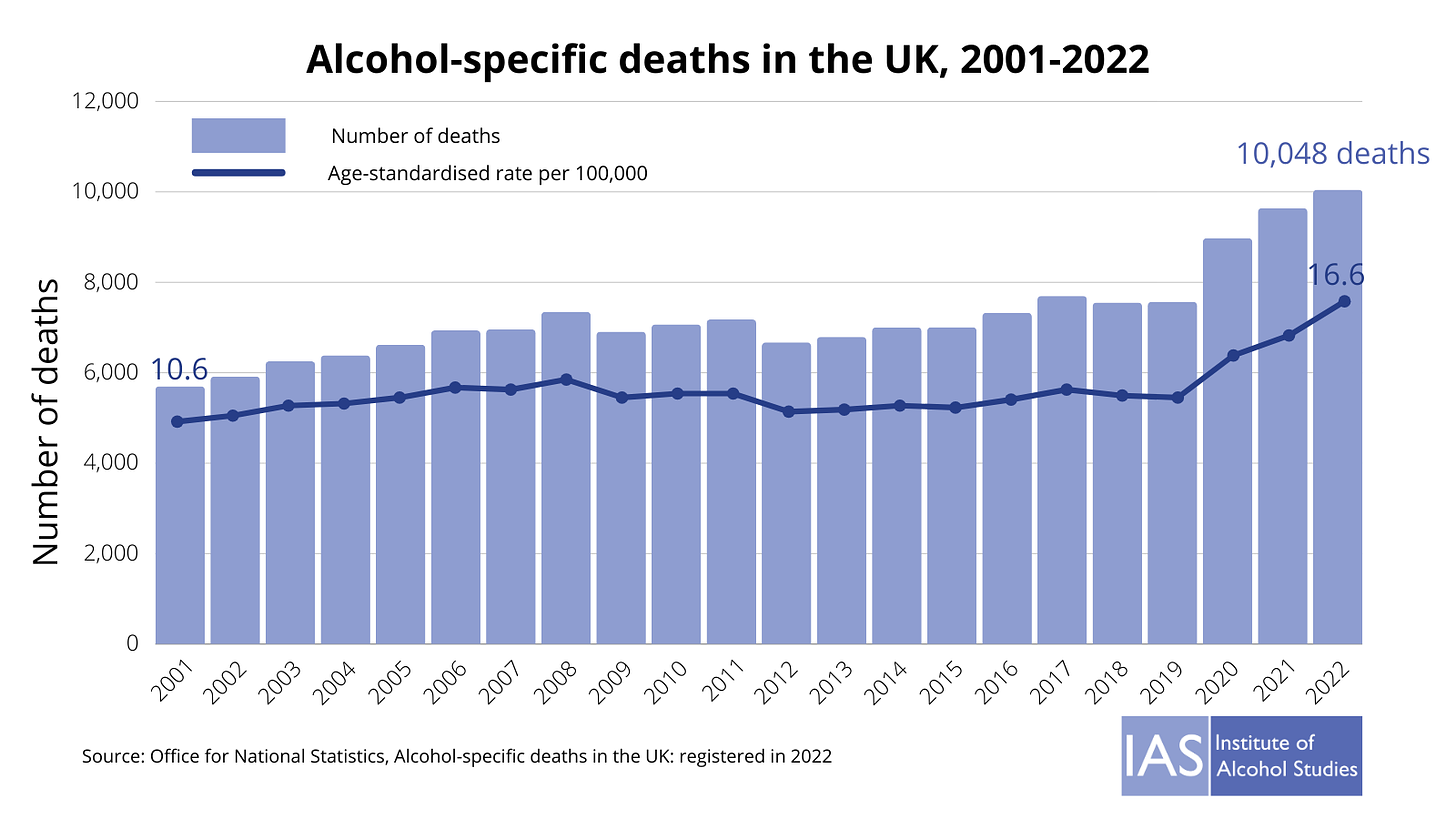

Alcohol-specific deaths reach another record high – podcast feature

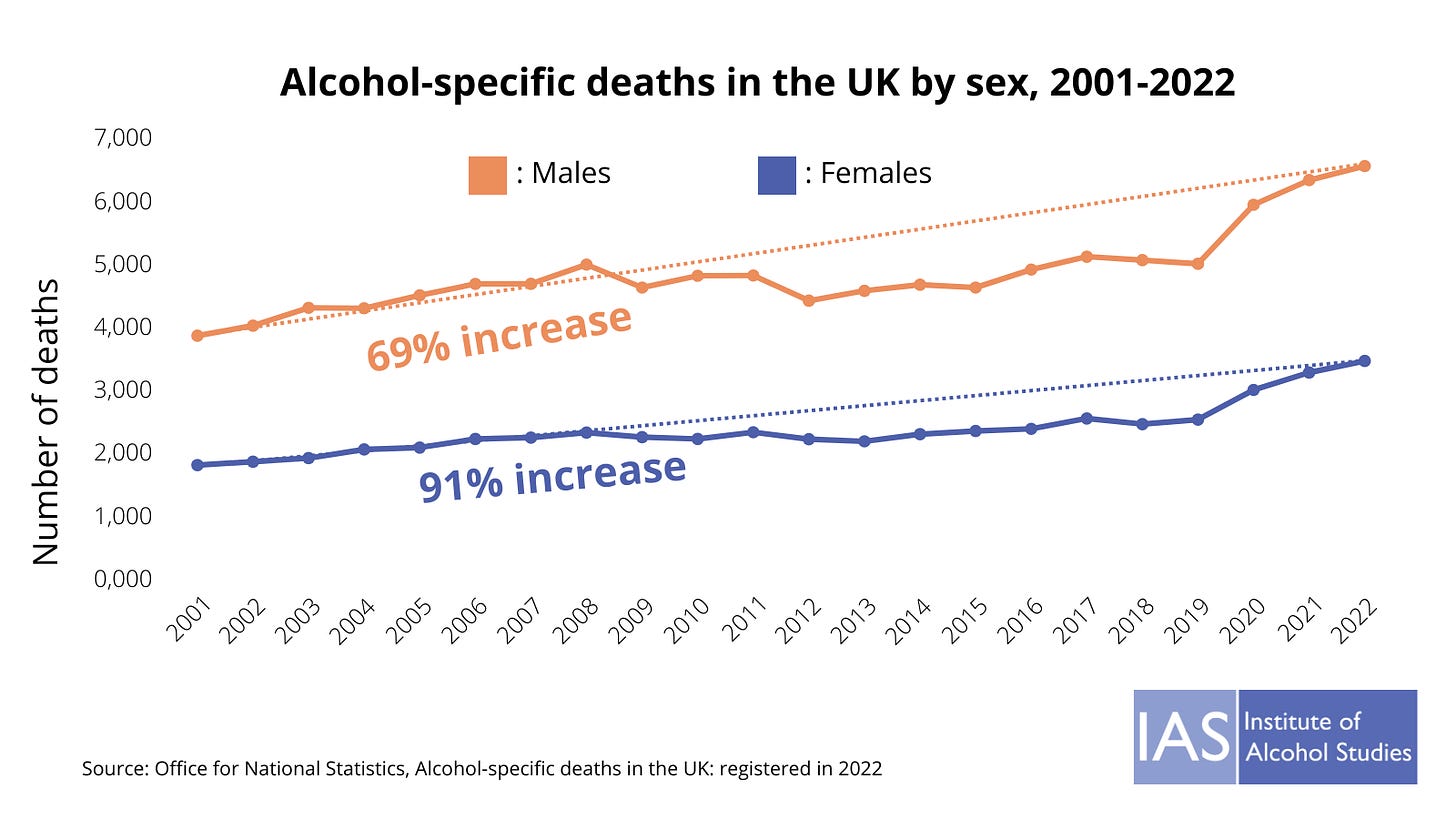

Deaths wholly attributable to alcohol reached a record high in 2022, with 10,048 people dying. This is the highest number of deaths since 2001 when recording began, and continues an upward trend since the pandemic. Before 2020, death rates had plateaued over the previous decade.

This is an increase of 4.2% compared to deaths in 2021 and a shocking 32.8% higher than in 2019. Since 2019, the rise in deaths was 37% among women and 31% among men. The death rate among men is still far higher, with twice as many dying.

IAS’s Chief Executive, Dr Katherine Severi, said:

“Year after year now we have seen tragic increases in deaths from alcohol, which disproportionately affect the most deprived communities in our country. The rise has also been especially high among women, with 37% more than in 2019. How many more deaths are needed before the UK government wakes up?

“Alcohol is the biggest killer of working age people. So even if the government doesn’t feel the moral imperative to act, there is a clear economic benefit of supporting people to live healthier lives.

“We know the public wants more action to reduce alcohol harm and we know how to do it: restrict irresponsible promotions, tackle ultra-cheap products with minimum unit pricing, and empower local leaders to control the availability of alcohol in areas with high rates of harm. It’s time to put public health before private profit. We simply can’t allow these deaths to continue to spiral.”

In the Financial Times, the Health Foundation’s Dr Adam Briggs, said:

“Supporting councils to consider public health as part of licensing decisions and restricting advertising in public places will help create healthier communities. At the national level, Scotland raised minimum unit alcohol pricing from 50p to 65p after a successful evaluation. Wales and the Republic of Ireland have followed suit and we can learn from their example.”

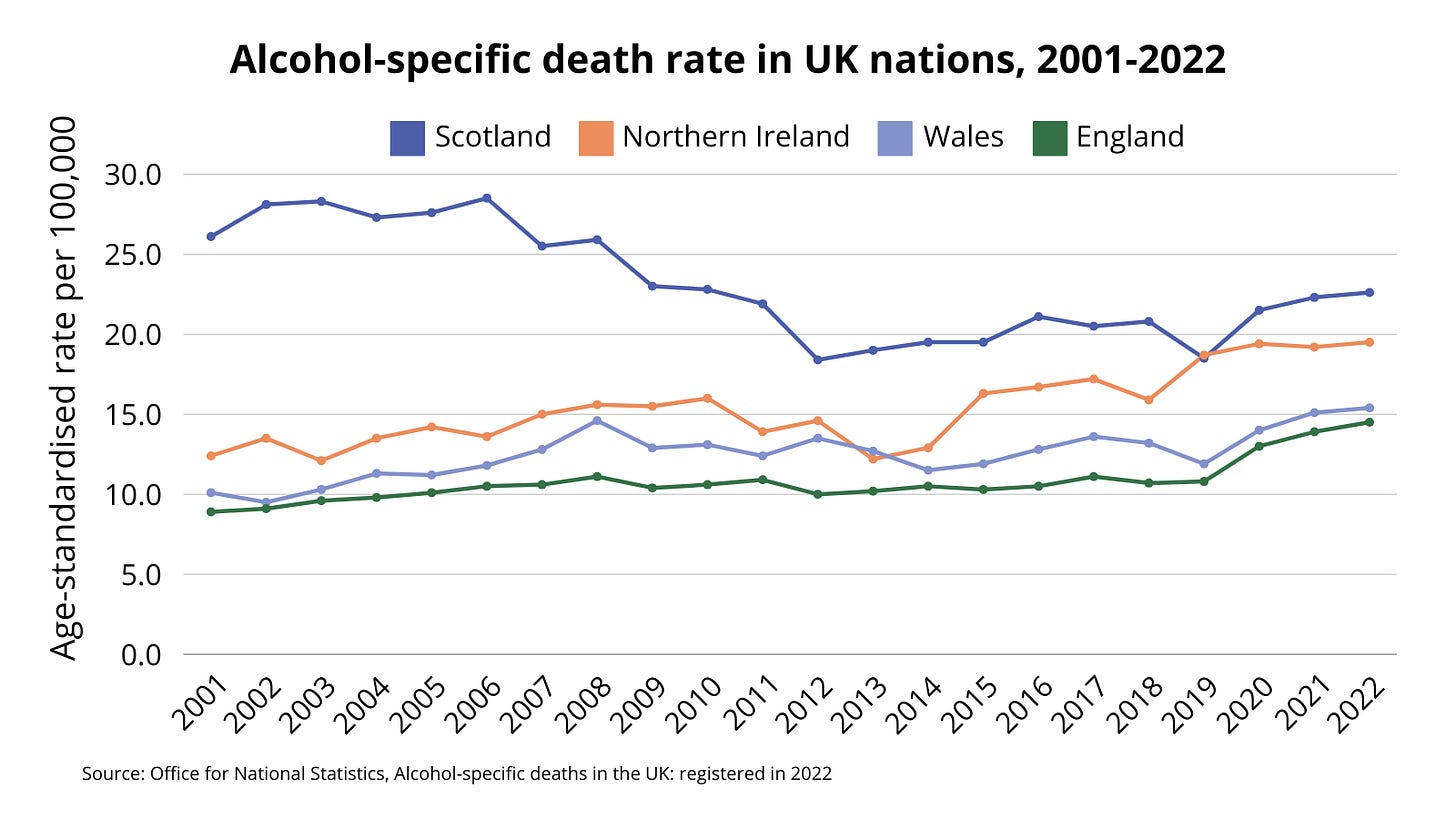

Scotland and Northern Ireland had the highest rates of alcohol-specific deaths, and the North East was the highest of any English region, with 22.6, 19.5, and 21.8 deaths per 100,000 people respectively.

Alcohol Focus Scotland’s Alison Douglas discussed the Scottish death rate:

“Despite the Scottish government’s acknowledgement that this is a public health emergency, we are still not seeing an adequate emergency response. Changes to drinking patterns during the Covid-19 pandemic have sadly become embedded and represent a ticking timebomb of alcohol-related illness and deaths for our already overstretched NHS.”

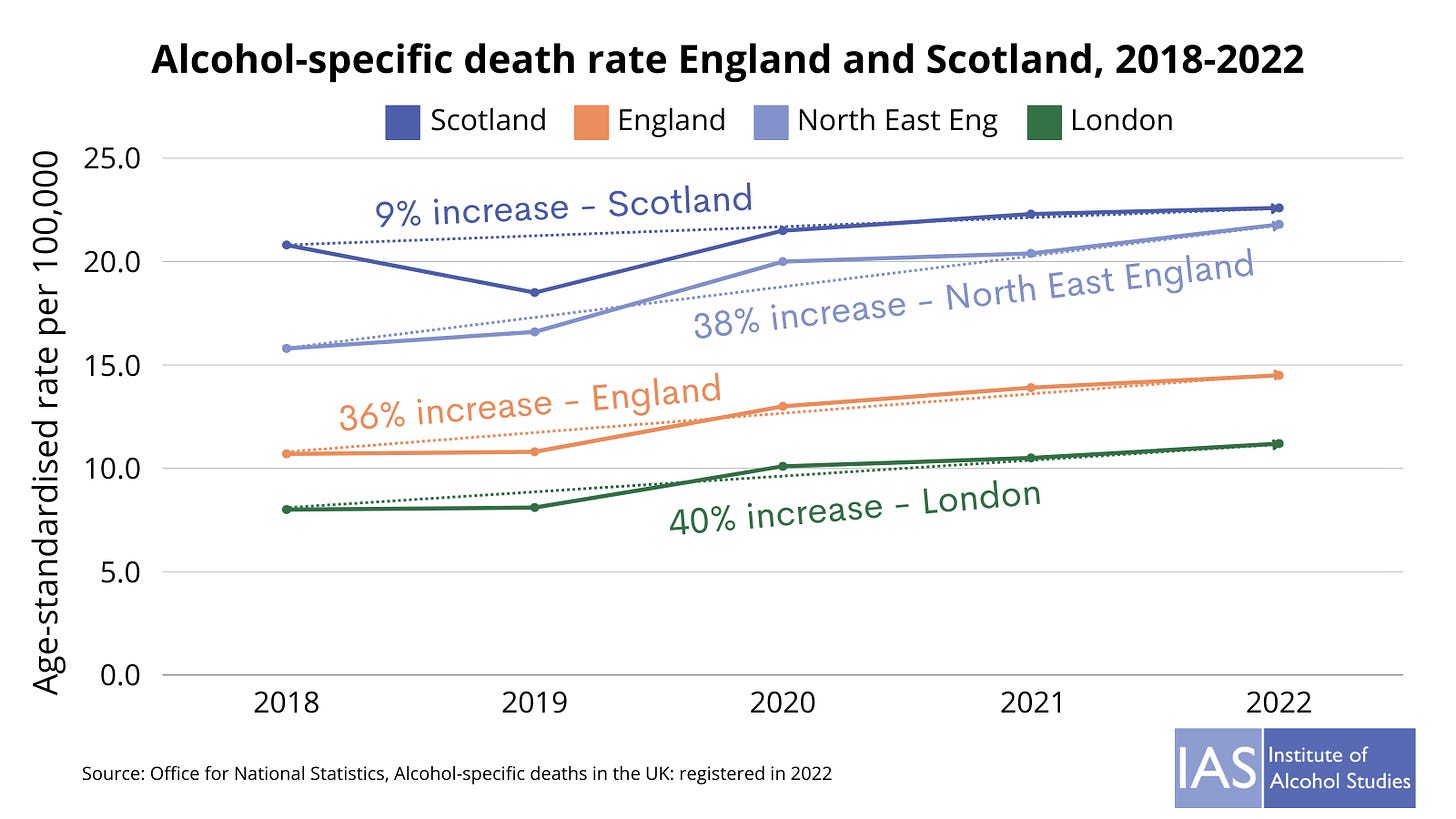

Although Scotland’s death rate is unacceptably high, it has come down significantly over the past 15 years. And the mitigating effect of Minimum Unit Pricing (MUP) is clear. Since it was introduced in 2018, all UK nations have seen increases in alcohol death rates, however in Scotland this has been far lower. As the following charts shows, Scotland’s death rate was 28.5 per 100,000 in 2006 and was 22.6 in 2022. In England those rates were 10.5 and 14.5 respectively. And from 2018 to 2022, the death rate in Scotland increased by 9%, whereas in England the increase was 36%. In fact, every single English region saw a bigger increase in its death rate than Scotland during these years.

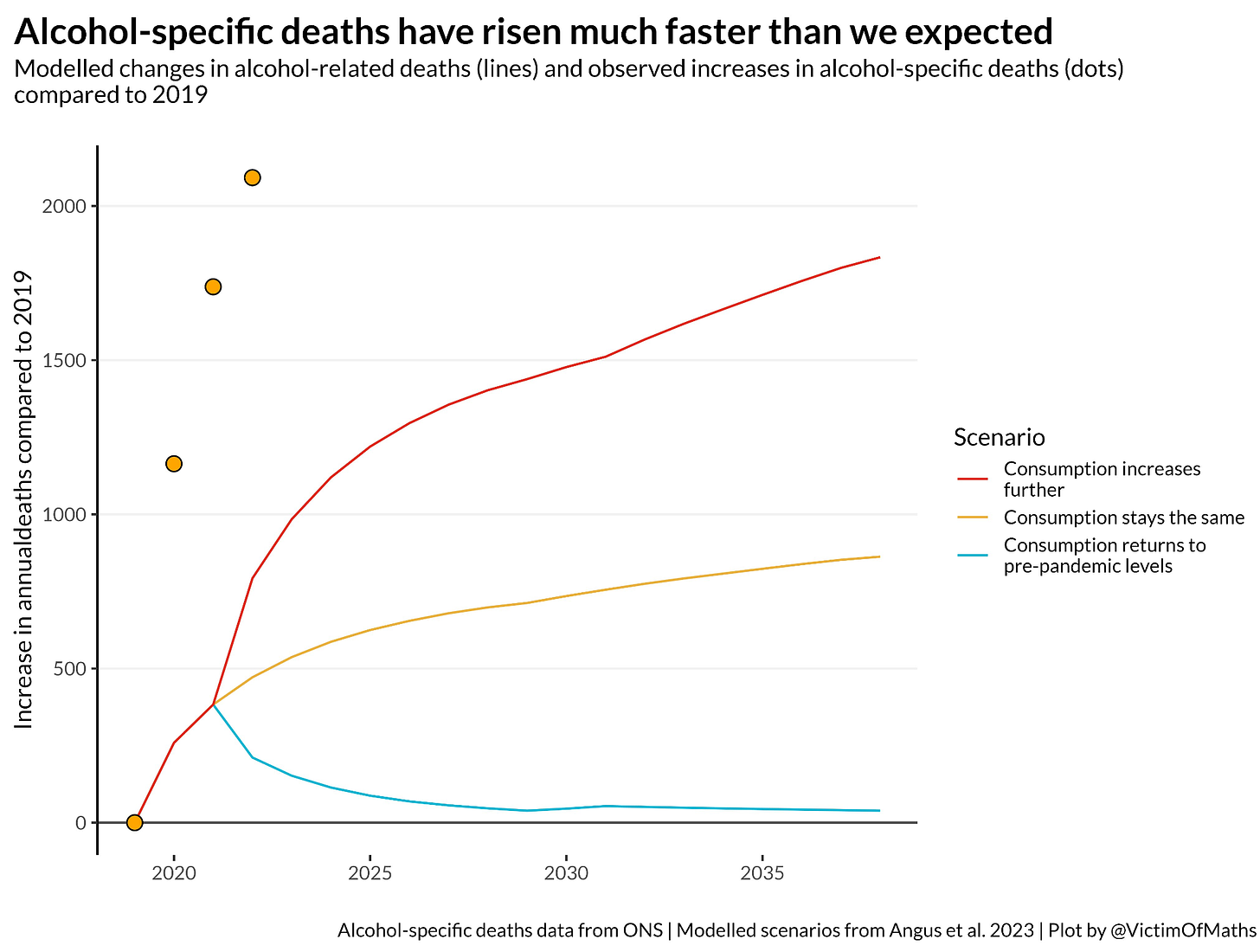

In 2022, the Sheffield Addictions Research Group published a paper which modelled how changes in alcohol consumption during the pandemic could lead to increased harm in the future, if drinking did not return to pre-pandemic patterns.

Health economist Colin Angus has developed a chart that compares these predictions against the actual ONS death data from 2022, and has shown that the modelling significantly underestimated the harm. He questions why this is the case, suggesting that access to treatment and perhaps other changes in heavy drinking habits may have contributed to this higher than expected harm.

Conservative MP Maggie Throup has joined public health voices in calling for a standalone alcohol strategy. Public health minister Andrea Leadsom said she would meet with Throup, but drew attention to the drug strategy funding as evidence of government action. You can watch the exchange here.

Minimum Unit Pricing will continue in Scotland and increase to 65p

On 17 April, the Scottish Parliament voted to continue Minimum Unit Pricing and to increase the rate to 65p per unit of alcohol, up from 50p. The increase will take effect on 30 September this year. The policy was subject to a sunset clause, meaning that it would automatically expire if parliament did not vote to continue it.

Drugs and Alcohol Policy Minister Christina McKelvie that she was “pleased that Parliament has agreed to continue MUP legislation and to raise the level it is set at”. She continued:

“Despite this progress, deaths caused specifically by alcohol rose last year – and my sympathy goes out to all those who have lost a loved one. However, as a letter to The Lancet by public health experts makes clear, it is likely that without MUP there would have been an even greater number of alcohol-specific deaths.”

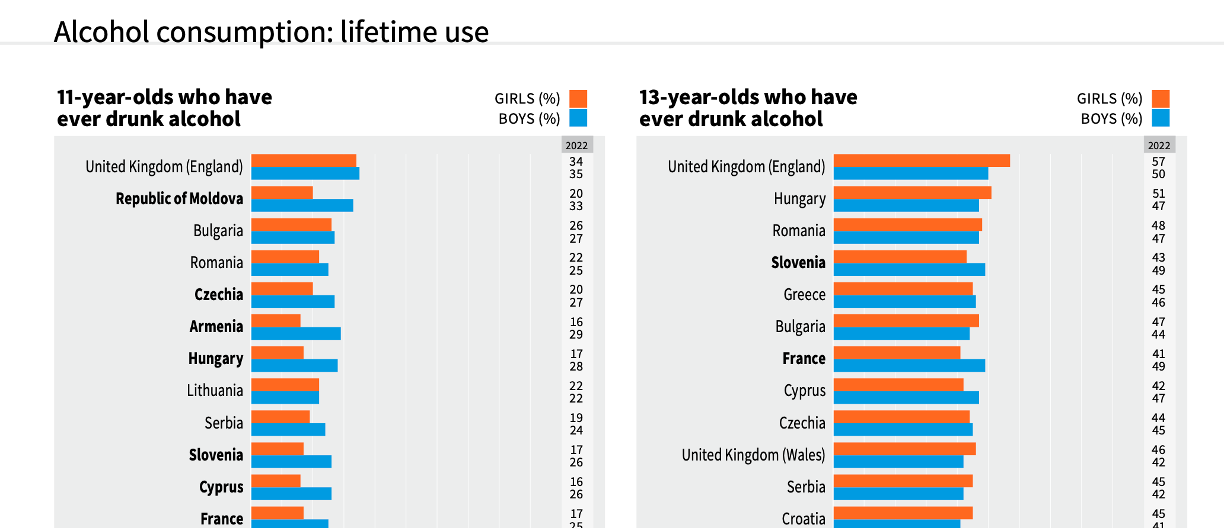

England has some of the highest rates of children drinking in Europe

A report by the World Health Organization suggests that England has some of the highest rates of children drinking in Europe.

England topped the list for 11 and 13 year olds who had ‘ever drunk alcohol’, although it was only 12th for 15 year olds who had.

For 11, 13, and 15 year olds who had ‘drunk alcohol in the last 30 days’ – which is deemed ‘current use’ – England was 5th, 3rd, and 14th.

In terms of 15 year old children who had been ‘drunk at least twice’, England came 9th. 34% of girls of this age had been and 22% of boys.

Dr Katherine Severi said that although youth drinking was in decline:

“The UK is one of the heaviest drinking nations in the world, and it’s clearly concerning that England has some of the highest rates of children drinking in Europe. People tend to have this perception that introducing children to moderate drinking is a good way of teaching them safer drinking habits. This is untrue. The earlier a child drinks, the more likely they are to develop problems with alcohol in later life.”

The data also show that children from more affluent households are more likely to drink. As Dr Severi told The Times:

“Evidence shows that parental drinking practices and how parents talk about alcohol are reflected in children’s attitudes towards alcohol and drinking. A pro-alcohol environment leads to the normalisation of drinking and ‘cultural blindness’ to alcohol harm among children. That’s true even with moderate parental drinking.

“And as more affluent people tend to drink more, this normalisation will be especially true, which is likely why we see higher rates of drinking in children from affluent families. We know that children mirror the behaviour of the adults around them, so it’s important that parents who drink any amount are aware of how it could affect their child in later life.”

Dr Hans Kluge, the WHO regional director for Europe, said:

“The widespread use of harmful substances among children in many countries across the European Region – and beyond – is a serious public health threat.

“Considering that the brain continues to develop well into a person’s mid-20s, adolescents need to be protected from the effects of toxic and dangerous products. Unfortunately, children today are constantly exposed to targeted online marketing of harmful products, while popular culture, like video games, normalises them.”

The Telegraph also highlighted alcohol industry education in schools, stating that:

“Meanwhile, public health experts have called for a ban on the alcohol industry educating Britain’s youngsters on “drinking responsibly”. Education programmes targeted at schoolchildren as young as nine are being funded by major alcohol producers such as Diageo, according to a BMJ investigation.

“Drinkaware, a charity funded by the industry, has a “freshers’ week survival guide” which tells students to load up on carbs before they go out and to drink water, but experts say they are downplaying the harms of drinking alcohol and being “selective” about the advice. The charity told the BMJ it followed guidance of the Chief Medical Officer and did not tell people to stop drinking “as it is considered a normal activity”.”

The Perils of Partnership – podcast feature

A research paper this month looked at correspondence between Public Health England (PHE), The Portman Group, and Drinkaware, in the run up to and launching of the Drink Free Days campaign, which ran in 2018-2019. The paper was featured in Private Eye above.

Researchers Dr Nason Maani, Dr May van Schalkwyck, and Professor Mark Petticrew used a Freedom of Information request to obtain communications between these groups, to better understand how PHE – a former government department – interacted with the alcohol industry and industry-funded charity.

The Drink Free Days campaign was controversial among the public health community at the time, due to the involvement of the alcohol industry. Professor Sir Ian Gilmore resigned from his role as an advisor to PHE due to the campaign, after stating that such campaigns were “more likely to improve the reputation of global alcohol corporations than improve the health of the nation”.

The correspondence highlights the collegial relationship between senior figures at PHE, The Portman Group, and Drinkaware, and also show how The Portman Group attempted to paint members of PHE’s alcohol advisory group as having a conflict of interest. For instance, they requested:

“…assurances that your conflict of interest assessments prevent those with links to the Alliance House Foundation, the Institute of Alcohol Studies, the Global Alcohol Policy Alliance…or any part of the temperance movement; from membership with the group.”

PHE was developing an evidence review at the time, which would ultimately lay out the overwhelming evidence that policies to reduce the affordability, availability, and marketing of alcohol reduce alcohol harm. These measures have been advocated for by public health charities for decades, yet The Portman Group sought reassurance that:

“…members of the group do not have track records in publicly campaigning for or against any of the alcohol policy evaluations your evidence review will be evaluating, as this would make it impossible for them to be objective or independent in their advice….”

This would essentially preclude any non-industry civil society body or researcher from involvement in the advisory group.

On our podcast, Dr Maani explained that these interactions are important as they show how alcohol industry involvement in health-related campaigns leads to civil society being pushed out.

In related news, the authors of the study recently published a piece in the BMJ, which highlighted the recent Health and Social Care Select Committee evidence session on alcohol prevention, which heard from the alcohol industry about how to reduce harm. They write that there was an absence of discussion on evidence-based policies and that witnesses from The Portman Group and the British Beer and Pub Association downplayed alcohol harm while claiming the industry has reduced youth drinking.

In a similar way to the Drink Free Days correspondence and attempts to cast aspersions on civil society, the Chief Executive of The Portman Group claimed without evidence that a labelling survey by the Alcohol Health Alliance was “…wrong. It is completely wrong”, while suggesting that their own survey was correct.

The BMJ piece explains that:

“This session shows how the choice of including industry and industry funded organisations in evidence gathering can shape the narrative, in ways that are consistent with maintaining industry interests, over population health.”

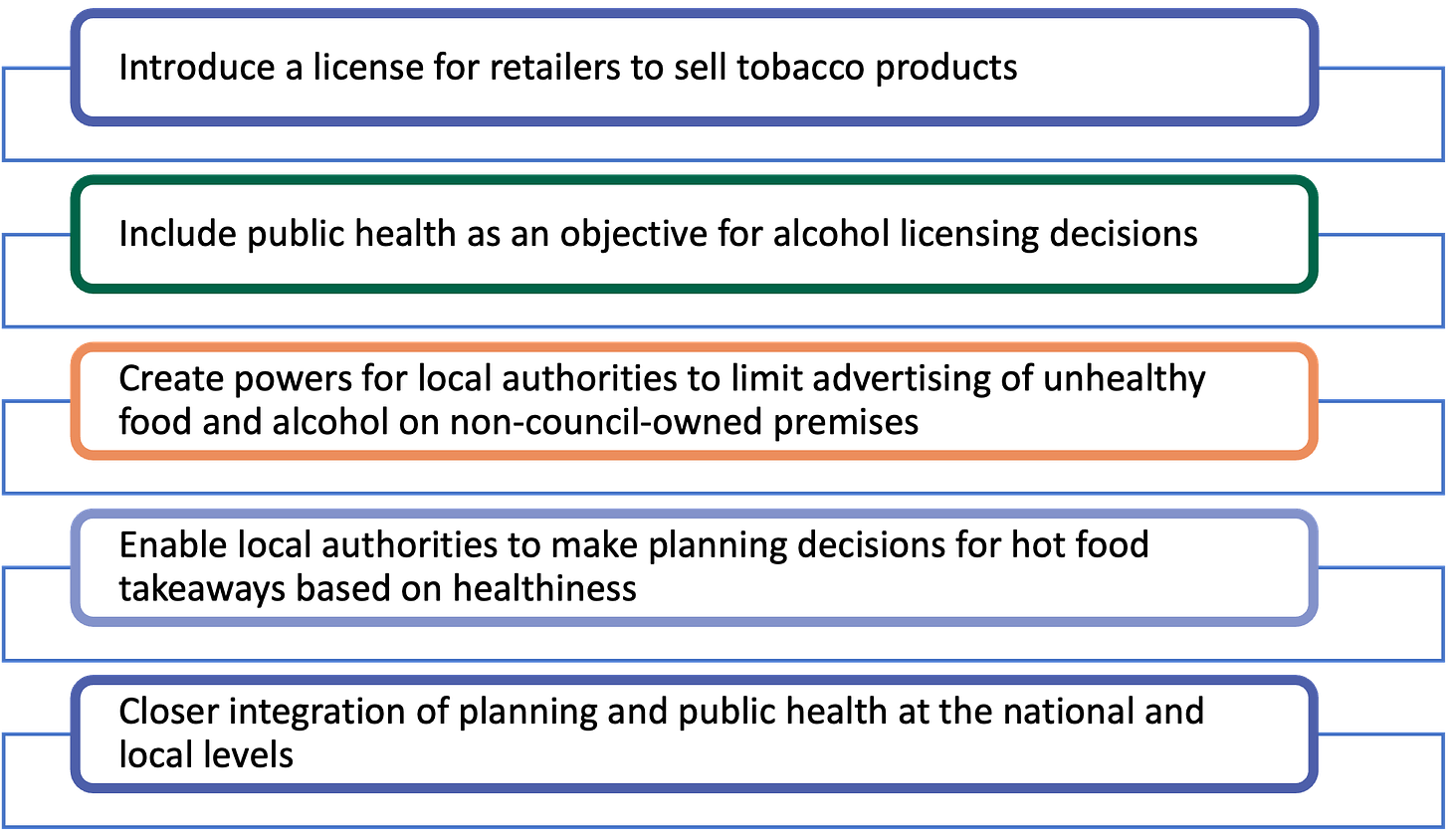

Changes to national policy to allow local government to address risk factors

The Health Foundation has published a briefing outlining five key proposals for national policy that would allow local government in England to do more to reduce harm from tobacco, alcohol, and unhealthy food:

The briefing states that:

“For the proposals to be most effective, national government must address shortfalls in local government funding and staffing. Without this, local authorities will not be able to maintain existing service levels, let alone take forward new opportunities.”

Back to Black Review: Avoids being stigmatising, but lacks much depth – Dr Sadie Boniface

IAS’s Head of Research, Dr Sadie Boniface, reviewed the recent Amy Winehouse biopic to see how Winehouse’s addiction to alcohol and other substances was portrayed in the film.

Dr Boniface explains that although alcohol is present in the film from the beginning, Winehouse’s concurrent mental health problems are less clearly signposted, despite the strong link and frequent coexistence between substance use and mental health problems. She writes that:

“The filmmakers’ choice not to show Winehouse’s other mental health problems too heavily is arguably a fair one, as the director, Sam Taylor-Johnson, has said she wanted the film to “joyfully honour” Winehouse. But the result is that Winehouse’s relationship with alcohol and other substances lacks nuance on the screen.”

The film appears to validate the notion of ‘drinking to cope’. Dr Boniface says we should be mindful of overly simplistic of depictions of self-medication:

“Research into post-traumatic stress disorder and alcohol use disorder found there was a lack of good evidence for the self-medication model. Alcohol use and mental health also have relationships that go in both directions, with evidence that mental health drives alcohol use and vice versa.”

Overall, Dr Boniface writes that while Back to Black avoids harmful and stigmatising representations of addiction and mental health, viewers don’t get a deep insight into the realities and complexities of addiction.

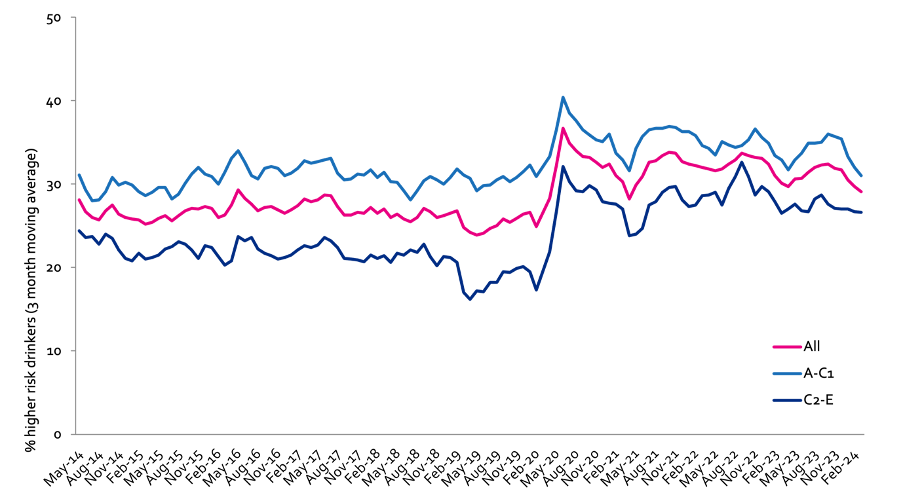

Alcohol Toolkit Study: update

The monthly data collected is from English households and began in March 2014. Each month involves a new representative sample of approximately 1,700 adults aged 16 and over.

See more data on the project website here.

Prevalence of increasing and higher risk drinking (AUDIT-C)

Increasing and higher risk drinking defined as those scoring >4 AUDIT-C. A-C1: Professional to clerical occupation C2-E: Manual occupation

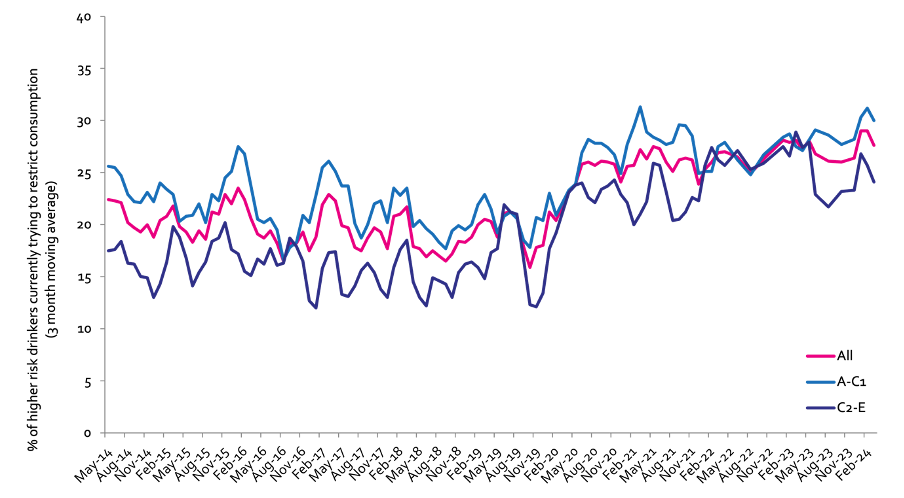

Currently trying to restrict consumption

A-C1: Professional to clerical occupation C2-E: Manual occupation; Question: Are you currently trying to restrict your alcohol consumption e.g. by drinking less, choosing lower strength alcohol or using smaller glasses? Are you currently trying to restrict your alcohol consumption e.g. by drinking less, choosing lower strength alcohol or using smaller glasses?

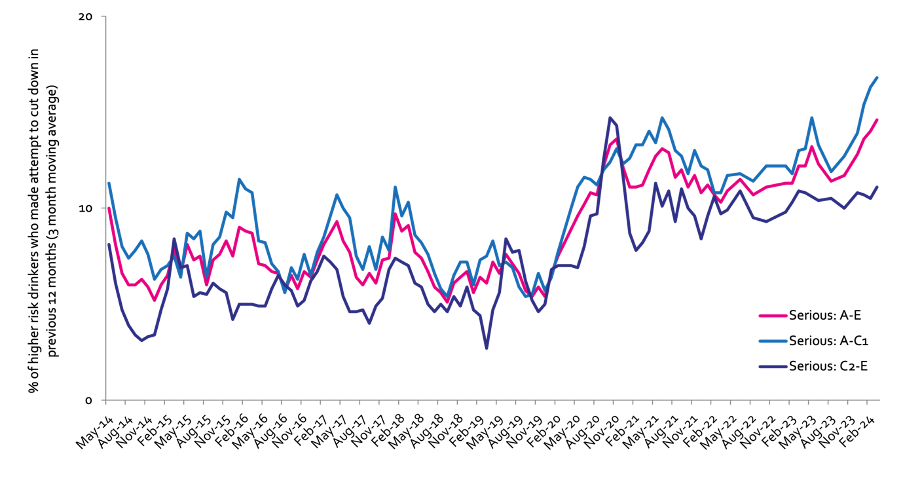

Serious past-year attempts to cut down or stop

Question 1: How many attempts to restrict your alcohol consumption have you made in the last 12 months (e.g. by drinking less, choosing lower strength alcohol or using smaller glasses)? Please include all attempts you have made in the last 12 months, whether or not they were successful, AND any attempt that you are currently making. Q2: During your most recent attempt to restrict your alcohol consumption, was it a serious attempt to cut down on your drinking permanently? A-C1: Professional to clerical occupation C2-E: Manual occupation

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

Gambling industry harms and parallels with the alcohol world

Will Prochaska –

Coalition to End Gambling Ads