In this month’s alert

Editorial – August 2018

Welcome to the August 2018 edition of Alcohol Alert, the Institute of Alcohol Studies newsletter, covering the latest updates on UK alcohol policy matters.

This month, a news report finds that three out of every five Brits have experienced drunken behaviour on flights. Other articles include: the alcohol industry relies on heavy drinkers; The Lancet’s Global Burden of Disease Study declares no level of alcohol improves health; and a study exploring the links between alcohol and dementia leads to some confusion in press reports.

Please click on the article titles to read them. We hope you enjoy this edition.

COVER STORY – Drunk, disruptive air passenger numbers on the rise

Report shows that 60% of fliers have encountered drunk passengers in transit

Fit to Fly report |

16 August – Three out of five British adults who travel by air (60%) have encountered drunk passengers whilst on a flight, according to a new report.

Fit to Fly, by the Institute of Alcohol Studies and the European Alcohol Policy Alliance, found that the majority (51%) of Brits believe there is a serious problem with excessive alcohol consumption in air travel. Drunk passengers who become aggressive on planes threaten the safety of other passengers, including children. Cabin crew have reported being sexually assaulted, kicked, punched and headbutted by drunk passengers.

Though it is an offence to be drunk on a plane, incidents of drunk and disruptive passengers have increased significantly in recent years, according to the Civil Aviation Authority, the body which regulates air travel in the UK. Fit to Fly finds that nearly a quarter of GB adults (24%) drink alcohol at the airport, and only 2% of adults reported drinking four drinks or more, indicating that a minority of passengers drinking excessively may be putting other passengers’ safety at risk.

The YouGov survey behind the report also found that:*

- 86% respondents support the same licensing laws applying to shops and bars selling alcohol in the airport as shops and bars on the high street

- 74% respondents support the restriction of alcohol consumption at airports to bars and restaurants only, meaning that alcohol bought at duty free cannot be consumed in the airport

- 67% respondents support a limit on the quantity of alcohol that people are allowed to consume in the airport

- 64% respondents support breathalysing at departure gates

- 59% respondents support drinking alcohol brought from home or bought at the airport on-board a plane to be an offence (excluding alcohol bought whilst on the plane)

- 55% respondents support time restrictions on when alcohol can be sold at airports

There have already been several reports in the media this summer about drunk passengers on planes, including cases where they have assaulted other passengers, or where flights have had to be diverted so that passengers could be removed from the plane.

Jennifer Keen, Head of Policy at the Institute of Alcohol Studies, said:

‘The start of a holiday should be a happy and relaxing time for families. Instead people can be put in scary and, sometimes, frankly dangerous situations by a minority of people who drink too much and become disruptive on planes.

‘The government needs to do more to protect ordinary passengers from those who get drunk and aggressive. There is no clear reason why shops and bars in airports should be exempted from normal licensing rules when drunk people in the air are a much bigger safety risk to others than drunk people in the high street.’

Fit to Fly follows a 2017 House of Lords Committee recommendation that the UK Government extend the Licensing Act 2003 to airside premises. Normal licensing laws don’t apply to premises in airports after security, which means there aren’t the same rules preventing sale of alcohol to people who are already drunk. The report calls on government to take action to tackle the problem by:

- Extending licensing laws so that bars and shops in airports are covered by the same laws as bars and shops in the high street

- Signing up to an international treaty to empower police forces on the ground to prosecute disruptive passengers

- Bringing in rules about duty-free alcohol so that anything bought in a shop is sent directly to the departure gate in a sealed container, or placed directly in the hold, to stop people drinking alcohol from a duty-free shop in the airport lounge.

Diarmuid Ó Conghaile, Ryanair’s Director of Public Affairs, commented: ‘Ryanair welcomes this report by the Institute of Alcohol Studies, highlighting the problems associated with the misuse of alcohol by a small number of passengers, which creates disturbance and disruption to others. Regulatory measures are available to address this problem, including amending licensing laws for airports and statutory prohibition of consumption on an aircraft of alcohol which a passenger has brought with him/her.

‘Problems do not arise from the sale of alcohol on board, as the measures are small, the flights short, and sales controlled by trained staff. Ryanair thanks the Institute of Alcohol Studies for its important contribution, and calls on the UK government to make the necessary changes.’

The government is expected to launch a call for evidence on the issue in due course.

* All figures, unless otherwise stated, are from YouGov Plc. Total sample size was 2016 adults, of which 1,792 have travelled by air. Fieldwork was undertaken between 13th – 16th July 2018. The survey was carried out online. The figures have been weighted and are representative of all GB adults (aged 18+).

You can hear actor Ally Murphy recounting the alcohol fuelled incidents on long-haul flights that she dealt with during her career as cabin service supervisor for Virgin Atlantic on our Alcohol Alert podcast.

Alcohol industry relies on heavy drinkers

Report finds that two-thirds of alcohol sales are those drinking above the UK guidelines

|

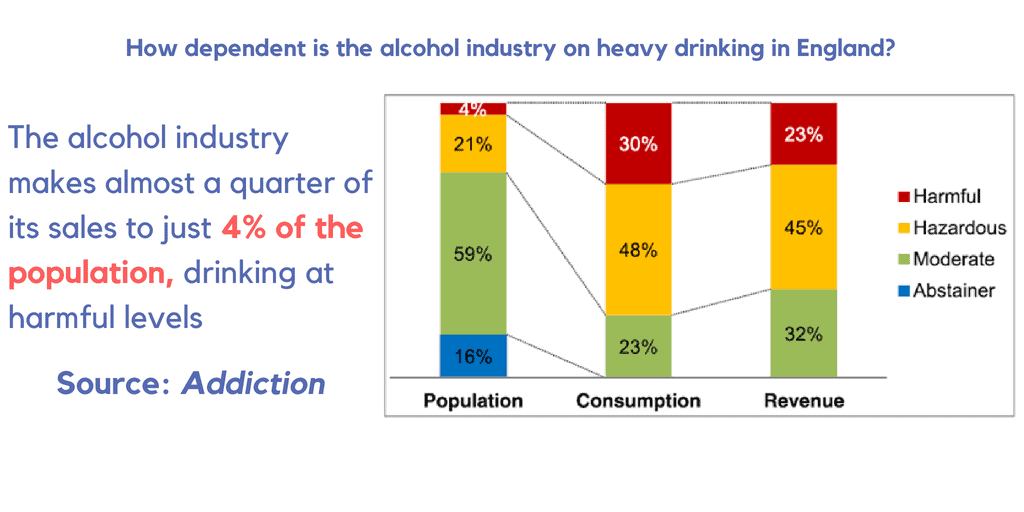

23 August – If all drinkers followed the recommended drinking guidelines, the alcohol industry would lose almost 40% of its revenue, an estimated £13 billion. This is one of the main findings of a new paper published in the journal Addiction.

The analysis, carried out by researchers at the Institute of Alcohol Studies and the University of Sheffield’s Alcohol Research Group, also shows that:

- Drinkers consuming more than the government’s low-risk guideline of 14 units (around one and a half bottles of wine or six pints of beer) per week make up 25% of the population, but provide 68% of industry revenue

- The 4% of the population drinking at levels identified as ‘harmful’ (over 35 units a week for women, over 50 units a week for men) account for almost a quarter (23%) of alcohol sales revenue (illustrated)

The results of the study appear to contradict industry rhetoric that moderate drinking is not a threat to their business model because they can encourage drinkers to ‘drink less, but drink better’, and trade up to more expensive beverages.

Instead, many producers and retailers may in fact have a strong financial incentive to ensure heavy drinking continues in order to stay profitable – not only do a higher proportion of sales in supermarkets and off-licences (81%) than pubs, bars, clubs and restaurants (60%) come from those drinking above guideline levels, but heavy drinkers also generate a greater share of revenue for producers of beer (77%), cider (70%) and wine (66%) than spirits (50%).

The research team estimates that the average price of a pint of beer in the pub would have to rise by £2.64, and the average price of a bottle of spirits in supermarkets by £12.25, to maintain current levels of revenue if everybody were to drink within the guideline levels.

The report’s findings raise questions about the appropriateness of the industry’s continued influence on government alcohol policy.

Aveek Bhattacharya, policy analyst at the Institute of Alcohol Studies, and the lead author of the paper, said:

‘Alcohol causes 24,000 deaths and over 1.1 million hospital admissions each year in England, at a cost of £3.5 billion to the NHS. Yet policies to address this harm, like minimum unit pricing and raising alcohol duty, have been resisted at every turn by the alcohol industry. Our analysis suggests this may be because many drinks companies realise that a significant reduction in harmful drinking would be financially ruinous.

‘The government should recognise just how much the industry has to lose from effective alcohol policies, and be more wary of its attempts to derail meaningful action through lobbying and offers of voluntary partnership. Protecting alcohol industry profits should not be the objective of public policy – previous research has shown that reducing alcohol consumption would not only save lives and benefit the exchequer, but could also boost the economy and create jobs.’

Colin Angus, research fellow in the Sheffield Alcohol Research Group at the University of Sheffield, and a co-author on the paper said:

‘These figures highlight an important conflict of interest in the UK Government’s approach to reducing alcohol problems. Its decision to work in partnership with the alcohol industry is unlikely to lead to effective policies when heavy drinkers provide a large share of the industry’s revenue.

‘The scale of price rises required to maintain current levels of revenue cast serious doubt on the alcohol industry’s claims that it supports moderate drinking.’

No level of alcohol improves health, says The Lancet

In fact, it is the seventh leading risk factor globally for mortality and disease

24 August – Alcohol control policies should focus on lowering overall population-level consumption in order to decrease death rates, according to The Lancet.

Their new Global Burden of Disease Study finds that alcohol was linked to 2.8 million deaths worldwide in 2016, 2.2% of all deaths in women and 6.8% in men, making it the seventh leading risk factor for mortality and disease.

Among the population aged 15–49 years, alcohol use was the leading risk factor globally in 2016, with approximately 4% of female deaths and 12% of male deaths attributable to alcohol use. For populations aged 50 years and older, cancers accounted for a large proportion of total alcohol-attributable deaths in 2016, constituting over a quarter (27%) of total alcohol-attributable female deaths and 19% of male deaths. The level of alcohol consumption that minimised harm across health outcomes was zero standard drinks per week.

Using 694 studies to estimate alcohol consumption and 592 studies including 28 million people to estimate associated risks, the study generated improved estimates of alcohol use and alcohol-attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 195 locations from 1990 to 2016, for both sexes and for five-year age groups between the ages of 15 years and 95 years and older. The health effects of alcohol were examined across 23 health categories, including cardiovascular disease, cancers, infectious disease, and injuries.

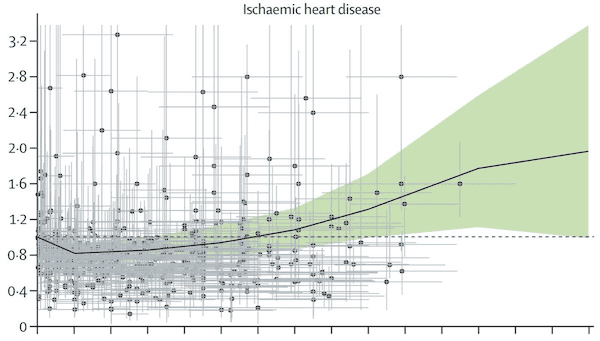

The study found that there was a small protective effect for heart disease in women who drink low amounts of alcohol, which was offset when the risks associated with all 23 diseases were combined (illustrated below):

|

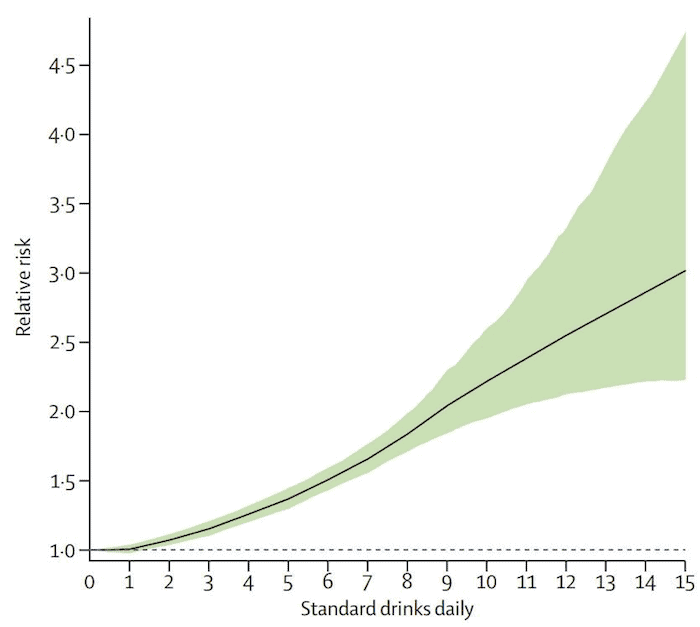

With all related health issues taken into account, the risks of all-cause mortality associated with alcohol increase with the amount consumed each day (illustrated below):

|

What’s the (relative risk of) harm?

Dr David Spiegelhalter, statistician and chair of the Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication, took issue with the notion of how The Lancet portrayed risk at the lowest consumption levels. As The Lancet press release stated, in comparing no drinks with one drink a day, ‘the risk of developing one of the 23 alcohol-related health problems was 0.5% higher – meaning 914 in 100,000 15–95 year-olds would develop a condition in one year if they did not drink, but 918 people in 100,000 who drank one alcoholic drink a day would develop an alcohol-related health problem in a year.’

‘That means, to experience one extra problem, 25,000 people need to drink 10g alcohol a day for a year’, or ‘400,000 bottles of gin’, wrote Spiegelhalter, ‘which indicates a rather low level of harm in these occasional drinkers.’

However, Dr Robyn Burton, of the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience at King’s College London commented on the study in an article titled ‘No level of alcohol consumption improves health’:

|

Alcohol Policy UK editor James Morris notes that Dr Spiegelhalter is one of several in his field who have argued for alcohol health advice to be refined such that the actual level of risk can be better determined by individuals, rather than a single one size fits all threshold of 14 units, and that ‘with a new alcohol strategy expected next year, efforts to capture the ears of policy makers on all such issues will no doubt be under way.’

Moderate drinking does not prevent dementia

Some newspapers misinterpret study as victory for alcohol consumption over abstinence

01 August –There is a link between heavy drinking and an increased dementia risk compared with drinkers who stick within the UK’s consumption guidelines, according to research published in the British Medical Journal.

However, the study gained much of its press coverage for the discovery that in certain instances, abstainers in middle age also had an elevated risk of dementia compared with those who drank within the guidelines.

An Anglo-French team of researchers evaluated the effects of midlife alcohol consumption on risk of dementia in 9,087 participants of the Whitehall II study over a mean follow-up of 23 years. Participants were stratified as abstainers; moderate alcohol drinkers, consuming 1–14 units/week (this group also served as the reference group); or excessive drinkers consuming 14 units/week or more – definitions based on the current UK Chief Medical Officers’ low risk drinking guidelines. Over the period, 97 people developed dementia, and this was more likely if they were smokers, were obese, had cardiovascular disease or had diabetes.

Long term consumption of >14 units/week was associated with an increased risk of dementia. In some cases, the authors were able to show that with every seven unit/week increase, there was a 17% increase in dementia risk.

Risk was also significantly increased among participants with at least one alcohol-related hospital admission, and presence of alcohol dependence. These findings are consistent with previous research, also from the Whitehall II cohort, reporting >14 units/week alcohol consumption is associated with atrophy (or deterioration) of the hippocampal area of the brain and faster cognitive decline.

Mortality was also found to be statistically significantly higher (31%) among excessive alcohol users and significantly increased (12%) with every seven unit/week increase.

Most intriguingly for the researchers, they noted that abstinence from alcohol in midlife, long term abstinence, and decrease in consumption were also associated with a significantly higher risk of dementia of 45%, 67%, and 50%, respectively, compared with moderate alcohol consumption, but ‘only among participants who reported abstinence from wine.’ Abstinence was also associated with a significantly increased incidence of cardiometabolic disease (14%). Dementia risk among abstinent participants with cardiometabolic disease was non-significantly increased, whereas dementia risk in participants free of cardiometabolic disease was not altered, suggesting a possible mediating role of cardiometabolic disease in dementia risk among abstainers.

The research team observed that abstainers were most likely to: be women; have attained lower education; be less physically active; be obese; and to have had a higher prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors, all associated with an increased risk of dementia, which could explain the differences. However, adjustment for confounding factors did not alter the findings.

The suggested that the properties of wine may have also made a difference to the outcomes of moderate drinkers as opposed to abstainers. They wrote: ‘Wine, in addition to alcohol, contains polyphenolic compounds, which have been associated with neuroprotective effects on both neurodegenerative and vascular pathways, and with cardioprotective effects through inflammation reduction, inhibition of platelet aggregation, and alteration of lipid profile.’ However, some researchers were quick to point out the likely socioeconomic status of those who drank wine as having some influence too.

Misleading headlines

Press coverage of the study, as NHS Choices notes, was largely accurate, except for the Telegraph (‘Middle aged drinking may reduce dementia risk, new study finds’) and the Sun (‘Drinking six pints of beer or glasses of wine a week could save you from deadly dementia’) newspapers, both of which falsely pitted moderate drinkers against abstainers.

Their critique of the coverage commented that ’while it’s true that people who did not drink, or who had the occasional glass, were also found to be more likely to develop dementia, we cannot say that alcohol protects against dementia. We do not know how much they drank when they were younger. These higher-risk people may have stopped drinking because of health worries, or possibly because some had concerns about their alcohol use when they were younger.

’Also, it’s worth noting that those who did not drink alcohol and did not have cardiovascular disease or diabetes were not at increased risk of dementia.’

Although a strong piece of research producing reliable results, one notable limitation was the source material – London-based office-based workers – whose lifestyle outcomes may not be reflective of the general population. It was also important to note that as a cohort study, it could only show an association between 2 factors, not that drinking (or non-drinking) was a cause of was caused by dementia.

Ultimately, more studies – preferably government funded – need to be conducted on the possible protective effects of light to moderate alcohol use on risk of dementia and the mediating role of cardiovascular disease, said researchers, who also warned that it could take some time to produce any meaningful results.

Alcohol addiction medications improve patient lives

Prevalence of suicidal behaviour, accidental overdose and arrest was reduced in patients by the majority of prescribed remedies

03 August – A study of 21,000 patients receiving treatment for alcohol and opioid use disorders with one or more of four commonly-used addiction medications (acamprosate, buprenorphine, methadone and naltrexone) measured the effect of treatment by comparing four key indicators in patients before and after beginning treatment: suicidal behaviour; accidental overdose; arrest for any crime; and arrest for violent crime.

All of the drugs – of which acamprosate and naltrexone are used to treat alcohol addiction – reduced suicidal behaviour by up to 40%, arrest for any crime by up to 23%, and arrest for violent crime by up to 35%. Acamprosate, naltrexone and buprenorphine also reduced accidental overdose.

Previous research has found these medications to effectively treat addiction, however this study, carried out by researchers at the University of Oxford, the Karolinska Institutet, the University of Colorado and Örebro University, Sweden, is the first study to show other beneficial social and health outcomes from a large-scale cohort of patients.

Suicide, overdose, violent and non-violent crime have negative consequences at the individual, community and societal levels. These findings indicate that prescribing alcohol and addiction medications could have diffuse positive effects both for the individual and wider society.

Distilled spirits strongest predictor of European male mortality

Excessive consumption best predicts deaths ahead of other predictors such as tobacco use

03 August – Findings from a new study suggest that patterns of excessive male mortality in European countries are strongly related to the average level consumption of distilled spirits – such as vodka, brandy, whiskey and rum.

Average male life expectancy has been steadily increasing in Europe since the 1940s, however many countries – especially in Eastern Europe – have much higher levels of male mortality than expected, in relation to their Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Whilst a number of factors – health expenditure, smoking, hard drug use, and low fruit and vegetable consumption – also predicted levels of mortality, the relationship between distilled spirits and mortality explained the greatest level of between-country variation in mortality. This relationship was particularly pronounced for distilled spirits, whereas per-capita wine consumption only a moderately significant predictor, and beer consumption did not significantly explain any of this variation.

These findings lend support to the use of targeted policies focused on reducing the consumption and harms related to distilled spirits, concluding that ‘reduction in distilled spirits consumption… should be a major target in health policy’. This study notes the global relevance of these highlighting that consumption of distilled spirits is not only an Eastern European issue, ‘but is also becoming a significant issue in some other regions of the world’.

UK drink drive casualties highest since 2012

Calls for cut in legal alcohol limit after over 9,000 casualties in 2016

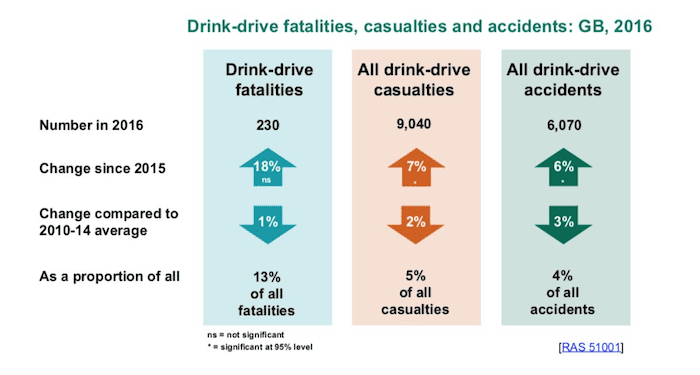

09 August – The number of drink drive casualties recorded in 2016 reached its highest since 2012, according to new figures published by Department for Transport.

An estimated 9,040 people were injured or killed on Britain’s roads in incidents where a driver was over the alcohol limit, a statistically significant increase of 7% on the previous year, representing about one in 20 of all casualties in reported road accidents in 2016. The total number of accidents where at least one driver or rider was over the alcohol limit rose by 6% to 6,070.

There were also an estimated 220 fatal drink drive accidents in 2016, another statistically significant increase from 170 in 2015 that indicates a return to levels seen between 2010 and 2014. The final central estimate of the number of deaths in accidents with at least one driver or rider over the alcohol limit for 2016 is 230, higher than the final figure for 2015 but not statistically significant.

Leading road safety charities expressed their concerns at the increases occurring across the board, with some pinpointing the UK drink drive limit of 80 milligrammes of alcohol per 100 millilitres of blood) as the primary cause of the issue. Scotland is the exception to the rule, having reduced its legal alcohol limit from 80mg per 100ml to 50mg almost four years ago.

Joshua Harris, the director of campaigns at the road safety charity Brake, said the law gave a ‘false impression’ that it was safe to drink and drive, adding that ‘even very small amounts of alcohol dramatically affect safe driving.’ He added: ‘How many more lives must be needlessly lost before the government acts on drink-driving? Today’s figures show that drink-driving is an increasing blight on British roads and yet the government sits on its hands and refuses to address the issue.’

Brake calls on the government to implement an effective zero-tolerance drink drive limit of 20mg per 100ml of blood, which would send a clear signal to drivers that ‘not a drop of alcohol is safe.’

Source: The Department for Transport |

Alcohol so cheap, says Alcohol Action Ireland

Off-trade ‘bonanza’ market worth €3.74bn, according to charity’s latest survey

09 August – An investigation into the pricing and affordability of alcohol in Ireland has highlighted the ‘remarkable affordability of alcohol to every day shoppers’. Conducted over seven days, Alcohol Action Ireland’s annual Alcohol Market Review and Price Survey 2018 recorded alcohol prices across all categories of alcoholic beverages in off-licence retailers in four locations. Using this data to calculate the cost per standard drink, or a unit containing 10ml of pure alcohol, the study found women could reach the Irish low risk guideline of 11 standard drinks for €5.49, and men, 17 standard drinks for €8.49.

Concerningly, this means that fatal quantitates of alcohol are affordable for less than €10, approximately equal to the hourly minimum wage of €9.55 per hour, or less than half that of the average hourly wage in Ireland, and described in The Irish Times as ‘pocket money prices’.

Cider was the most affordable of all drinks, followed by beer and spirits. Notably, cider was ‘universally cheap’ across all types of retailers, from large supermarkets to small off-licences, in both rural and urban locations, where gin, whiskey and beer were often equally affordable in these different contexts.

The report cites a ‘sophisticated retailing model’ as responsible for low prices across the off-licence retail sector, estimated to be worth €3.74 billion in 2017, where ‘at home-drinking’ is 50% more affordable than in 1998, according to The Irish Times.

These findings support the ‘urgent need’ for minimum unit pricing, as the Irish Government seeks to pass this legislation, which would also introduce health warning on labels.

Higher alcohol taxes still the ‘best buys’

Updated WHO research confirms that increased alcohol taxation is still most cost-effective policy to decrease consumption

15 August – A recent study undertaken by the World Health Organisation (WHO) has reaffirmed that increasing excise taxes on alcohol is the most cost-effective policy option to reduce alcohol consumption.

The study compared the costs of implementation, relative to the size of the health benefits gained in a population for five different policy options using over a decade of data collected from 16 different countries. These were: excise taxes; marketing restrictions; reduced hours of sale; drink-driving laws; and, providing brief psychological interventions to those consuming alcohol harmfully.

Of all the options, an increase to excise duty by 50% was the most efficient policy, costing less than $0.10 (USD) per capita to implement, with a high level of benefit for a given cost – less than $100 per year of healthy life gained by the policy in high- and low-income settings. Meanwhile, restricting hours of sale and marketing were also relatively cost effective, less than $100 per year of life gained in low-income settings and $500 in high-income settings.

Recognising that alcohol directly accounts for over 5% of deaths and 4% of disease, worldwide, such an assessment was first undertaken in 2004, coming to a similar conclusion. However, in many countries, excise duties on alcohol remain low.

According to WHO’s Dr Daniel Chisholm, co-author of the study, ‘low levels of awareness of health risks related to alcohol consumption and strong lobbying from the industry often lead to low excise taxes’.

Dr Carina Ferreira-Borges, also of the WHO, stated that the new evidence will ‘help to guide decision-makers to implement and enforce stronger measures that address the harms associated with alcohol use’.

North East landlords blame cheap supermarket alcohol for pub closures

Publicans cite cheap alcohol in off-licences and supermarkets as number one reason for closing pubs, survey finds

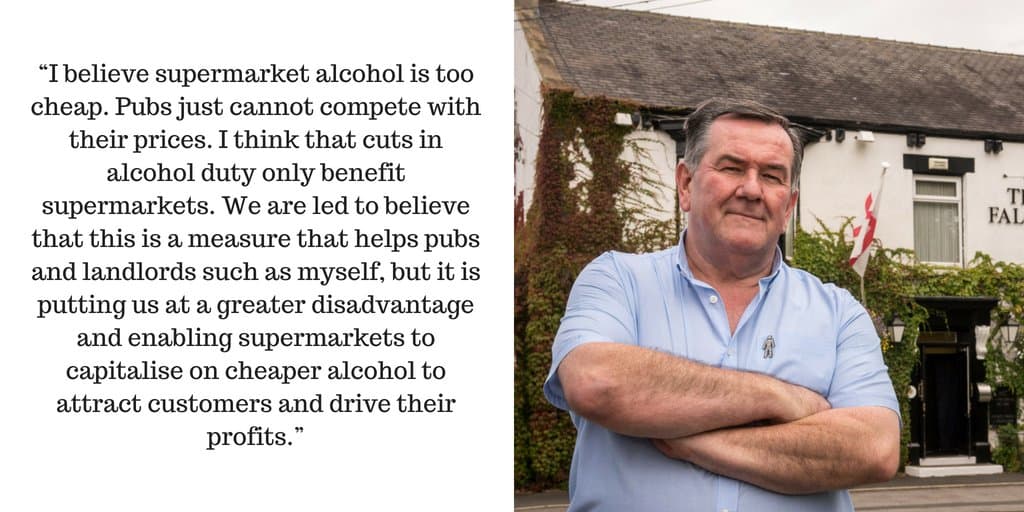

17 August – A survey of 200 publicans across the North East of England on the factors putting pressure on British pubs has found that landlords see cheap supermarket prices as the number one factor resulting in closures.

In contrast, cuts to alcohol duty, which are often proposed as a means to help struggling pubs, were only seen as a benefit to business by 7% of publicans. Indeed, previous research indicates that such measures, which reduce supermarket prices, actually disadvantage pubs further, by increasing a shift to buying from supermarkets.

Despite this, cuts have been made for five out of the past six years, and are estimated to cost HM Treasury £8.1 billion by 2023, equating to 34 million emergency ambulance call-outs.

The study, conducted by Balance North East, also showed that roughly half of publicans supported minimum unit pricing, with 78% wanting stricter drink-driving legislation.

Pub manager and Newcastle City Pubwatch Vice Chair Kevin Hindmarsh said: ‘We need to bring in minimum unit price to help combat the sale of cheap alcohol and the impact it has on our communities… [publicans] haven’t felt any benefits of alcohol duty cuts. They are only making alcohol cheaper in supermarkets, rather than helping to support pubs’.

Others agreed with this sentiment, with publican, David Simpson, adding that ‘cheaper alcohol is partly to blame for a lot of crime and disorder’, as cheap supermarket prices encourage ‘pre-loading’ and street drinking, and landlord Ian McNaughton, of The Falcon Inn near Yarm (see below).

Landlord Ian McNaughton, of The Falcon Inn near Yarm |

Areas with more alcohol vendors have higher hospital admission rates

Alcohol Research UK study finds positive correlation between density and rates of attendance to hospitals

20 August – A novel study by researchers at the University of Sheffield has found a correlation between density of alcohol vendors and rate of hospital admissions for conditions which are ‘wholly-related to alcohol’, for both acute and chronic conditions.

Using hospital admissions data for acute conditions, such as vomiting or drunken behaviour, and chronic health problems, like alcoholic liver disease, the researchers were able to correlate higher densities of alcohol-selling venues with higher levels of such admissions across England. The rate of hospital admissions in areas with a high density of alcohol vendors such as bars, pubs and clubs is 13% higher for acute, and 22% higher for chronic, conditions attributable to alcohol.

The study, funded by Alcohol Research UK, is among the first to show this relationship separately for both categories of illness – acute and chronic.

Higher rates of acute and chronic conditions wholly-related to alcohol were also correlated with higher densities of restaurants selling alcohol and convenience stores. Meanwhile, increasing density of supermarkets also saw modest increases in acute and chronic conditions. Results for diseases ‘partially-related to alcohol’ were less conclusive.

This study supports that for a range of vendors, the resulting increase in availability translates directly into acute and chronic ill-health.

Professor Ravi Maheswaran, author of the study, told Science Daily there is emerging evidence ‘that local licencing enforcement could reduce alcohol related harms’.

Dr James Nicholls, of Alcohol Research UK, added that this study adds weight to the argument that licensing needs to ‘think about the overall level of availability [of alcohol] in a given area’.

What is responsible drinking? Half of us don’t know

And only a third of us tell doctors how much we do drink

Dr Niall Campbell |

22 August – New research conducted by the Priory Group has found that most UK adults have poor awareness of weekly limits relating to units of alcohol, with 47% of adults being unaware of the recommended limit of 14 units for both men and women.

Consultant psychiatrist for the Priory, Dr Niall Campbell (pictured), suggests this may relate to low knowledge of what a ‘unit’ – which contains 10ml of pure alcohol – constitutes, telling the Metro that ‘to talk about “units” of alcohol frequently confuses people, because many think a unit is a glass of wine almost regardless of its size, and some pubs and restaurants only serve large glasses’. Indeed, over 50% surveyed felt that the government should improve communication about what a ‘unit’ is.

As reported in the Metro, nearly 70% also agreed that drink manufacturers had a responsibility to warn individuals about the links between alcohol and diseases such as cancer and liver diseases, where alcohol is linked to over 200 types of disease and injury.

Finally, over 60% were unaware about what could be classified as ‘binge drinking’, as defined by the NHS as drinking more than six units in a single drinking episode.

Overall these findings suggest a low public awareness of the health risks of alcohol, highlighting a need for new methods to convey these risks to the public, such as alcohol bottle labelling.

This information comes as another poll from Direct Line Life Insurance found that only a third of patients tell doctors how much they really drink.

According to the Daily Express, when asked why they gave a different figure, a fifth said they never kept track, a sixth said everyone misrepresents how much they drink, one in seven said it was irrelevant, and the same number feared their doctor would judge them. As a result, ‘nearly half of all GPs, believe they are hoodwinked and apply an “alcohol multiplier” for a more accurate picture.’

Professor Helen Stokes-Lampard of the Royal College of GPs said: ‘Overconsumption of alcohol can have a huge negative effect on our health and wellbeing so being honest with your GP or another healthcare professional, as well as yourself, is an important first step in understanding how it could be impacting your life.’

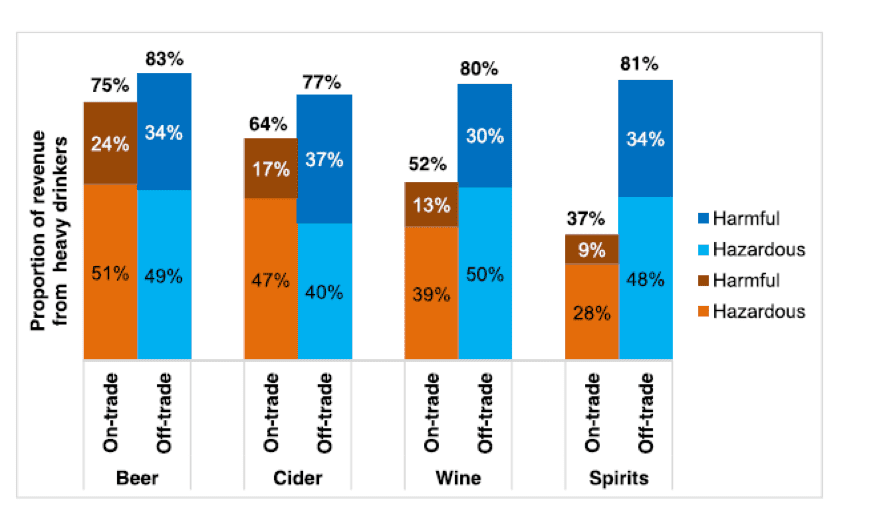

ALCOHOL SNAPSHOT – Beer and cider industries most reliant on heavy drinking

As described in ‘Alcohol industry relies on heavy drinkers’, researchers from the Institute of Alcohol Studies and the Sheffield Alcohol Research Group looked at the alcohol industry’s reliance on heavy drinking in a paper that appeared in the journal Addiction this month. Overall, they found that 68% of alcohol sales revenue in England comes from drinkers who consume more than the Chief Medical Officers’ low risk guideline levels of 14 units per week.

However, the paper also broke this figure down to establish how this varies between different sections of the alcohol industry. The chart below shows the proportion of beer, cider, wine and spirits sales in both the off-trade (supermarkets and off-licences) and the on-trade (pubs, clubs, bars and restaurants) to drinkers above guideline levels. It further splits this between hazardous drinkers (men consuming 15-50 units a week, women consuming 15-35 units a week) and harmful drinkers (men consuming over 50 units a week, and women consuming over 35).

|

It shows that sales to drinkers above guideline levels account for a higher share of sales in the off-trade, and that the proportion of sales to this group are around 80% for all beverage types. In other words, supermarket alcohol of all types is equally likely to be sold to heavy drinkers. On the other hand, consumers of different drink types vary far more in the on-trade. Nearly 75% of beer sales in the off-trade are to drinkers above the guidelines, whereas only 37% of spirit sales are. This may be because prices for spirits in the on-trade are relatively high. Overall, while much of the alcohol industry is exposed to heavy drinking, this does vary by beverage type and retailer.

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

Gambling industry harms and parallels with the alcohol world

Will Prochaska –

Coalition to End Gambling Ads