In this month’s alert

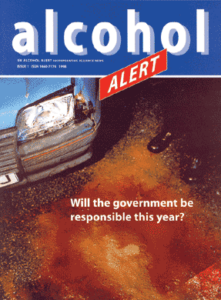

New lower legal limit on the way?

There is a question mark over the government’s intention to lower the drink drive limit. Despite all indications being that this would have overwhelming public support, reports state that there are divisions in the Cabinet, with the Prime Minister himself remaining unconvinced. Ministers questioning the lower limit cite the “nanny state” image and damage to country pubs as their main concerns.

This takes place against the backdrop of the consultation document, Combating Drink-Driving – Next Steps, recently issued by the Department of the Environment, Transport, and the Regions. The intention is to establish a long-term strategy to reduce road casualties and, notwithstanding the reported rifts among ministers, the Department sees tackling the problem of drink-drive accidents as central to this.

At the same time, the all-party House of Lords committee which considers proposals from the European Union has recommended that the drink-driving limit should be cut from 80 to 50 milligrams of alcohol per 100 millilitres of blood. The committee says that it has reached this decision “on balance”. It feels that simply lowering the limit will have only marginal effect on the number of accidents and that the measure will only be effective if combined with severer penalties and determined enforcement which the committee describe as “by a long way” the best means of dealing with the drink-drive problem.

The government has identified three main problem areas:

- hardened drink-drivers, in particular repeat offenders (around 12 per cent of offenders are convicted of a second offence within 10 years);

- drivers who are not above the current limit, but nevertheless impaired (studies dating back to the 1960s show convincingly that impairment and the risk of a driver’s involvement in a road accident begin, for most drivers, well below the current limit);

- young men, particularly in their twenties, who are disproportionately involved in drink-drive accidents.

The government sees three main fronts on which these problems have to be met: improving enforcement; improving the system of offences and penalties; and education publicity and information.

Enforcement

One alternative being considered is the increasing of police breath-testing powers. At the moment the police need to establish reasonable grounds of suspicion when a driver has not been involved in an accident and does not appear to have committed a moving traffic offence, but drivers “who are skilful at concealing their impairment are therefore difficult to bring to book.” The government is not minded to allow the police unfettered powers but considers that there may be a case “for allowing the police to require a breath test without prior suspicion if that power is used only for a specified period at a particular location.”

As part of the drive to speed up criminal proceedings, it is hoped that the time taken in bringing drink-drive cases to court will be greatly reduced. Too often, there are long periods when an offender remains free to drive whilst awaiting trial.

50mg Limit

The document makes the point that “about 80 road users per year are killed in accidents where at least one driver had blood alcohol over 50mg but where no driver had blood alcohol over 80mg.” The government thinks that at least 50 of these lives could be saved if the legal limit were reduced to 50mg “and enforced as efficiently as the current limit.” The estimate is that, in addition, approximately 250 serious and 1200 slight injuries could be prevented.

Although the courts have a wide degree of discretion in imposing fines and custodial sentences, the law sets a minimum 12 month disqualification period for a drink-driving or drug-driving conviction. The government considers it a matter for debate “whether a virtually automatic 12 months disqualification can still be justified in the context of a 50mg limit, or whether there should be a shorter minimum period, or possibly penalty points only, for offences between 50mg and 80mg.” Clarity, simplicity, and comprehensibility are the virtues of a single limit and a single penalty. Disqualification for a year is also a powerful deterrent. “On the other hand,” the consultation document continues, “as the degree of risk is less in the 50-80mg range and the risks rise particularly sharply at around 80mg, there is some logic in a lesser penalty for offenders between 50 and 80mg.” This latter course would be in line with practice in most European countries. “The Government would welcome views on whether, in the event of lowering the legal limit to 50mg: a) the current 12 months period of disqualification should be retained, or b) for offences in the 50-80mg range there should be a reduced period of disqualification, or even a lesser penalty such as a number of penalty points.”

High-risk offenders are defined as those convicted with a level of 200mg or more, those in court on a second or subsequent charge, and those who refuse unreasonably to give a sample. Although the penalties are effectively tailored to these offenders at the moment (a maximum fine of £5,000 or 6 months imprisonment; an unlimited fine and 10 years, if a death is involved), the government intends to give more publicity to these sanctions in order to increase their deterrent value.

A lower legal limit for young or newly qualified drivers for a specific period after their test is being considered but, although this has been used in other countries, enforcement problems are foreseen.

Education

The government is anxious to improve the provision and dissemination of suitable educational material so that school children are made thoroughly aware of the dangers of drink-driving. At the same time, there is a commitment to find ways of making sure that drivers are better aware of the relative strength of drinks. Thanks to Health Education initiatives, and a hitherto voluntary scheme among producers, information on units of alcohol is becoming more widely available.

The government also wants to know what the public thinks about the self-testing breathalyser which is now marketed in the United Kingdom and is widely used in France. One problem with this is that drivers might be tempted to drink up to the limit rather than the point where they began to feel uneasy about using their cars.

Your views sought

The consultation paper is aimed not just at representative or special interest bodies but at members of the public. Combating Drink-Driving may be obtained from the Department at the address below:

Your views and suggestions should be sent by 8th May to:

P.H. Openshaw Road Safety Division Department of the Environment, Transport, and the Regions Zone 2/13, Great Minster House, 76 Marsham Street, London SW1P 4DR.

Letter to the Editor

As a police officer I saw the misery caused by drinking and driving. That experience was no protection when my 21 year old daughter was killed by a drunken driver.

In our devastating grief, we began to discover that alcohol related deaths and injuries were seriously underestimated in official statistics and drinking drivers were getting away with disproportionate penalties, even after killing someone.

In 1985 the Campaign Against Drink Driving (CADD) was founded by victim’s families, since when we have seen many more lives saved through increased breath testing, more appropriate penalties, and growing public support for zero tolerance towards drinking and driving.

Despite this, the victims’ families still ask, “Why does the UK limit of 80mgs of alcohol per 100mls of blood condone a situation where drivers are 9.5 times more likely to crash their cars than those who have not drunk anything?”

A heartfelt cheer went up in victims’ families’ homes when the new Labour Government announced that it was considering a lower limit, but this has turned to apprehension over reports of indecision and ‘cold feet’. Members of CADD have fought for a reduction in the drink drive limit so that other families should not have to suffer as we did. It would appear that the same vested interests which Barbara Castle so bravely fought thirty years ago are still with us today.

The claim by the Brewers and Licensed Retailers Association that a 50mg limit will be the death knell for country pubs is no more valid today than it was with similar claims over 80mgs thirty years ago.

I appeal to all readers of Alert to write to the Prime Minister and Deputy Prime Minister urging them to end the indecision and introduce a 50mg limit without delay.

Surely a life saved is worth more than a pint of beer?

Graham Buxton MBE

Alcohol policy in question

The “sensible drinking” approach to reducing alcohol-related problems is being re-examined by the government in the context of its health strategies for England, Scotland, and Wales.

The government has made it clear that it intends to tackle drinking and driving and alcohol-related violence. Ministers are anxious to distance themselves from the image of their’s as the nanny state party, and, in the green papers recently issued, they appear to be undecided as to whether they wish to continue the “sensible limits” approach to alcohol education and to keep in place the health targets based on those limits promulgated by their Conservative predecessors.

However, whilst soliciting views on this issue, Health Ministers have given their backing to the Portman Group’s new campaign, “It All Adds Up!”, which seems to indicate that the revised “sensible drinking” limits introduced by the previous government will be endorsed. Tessa Jowell, Win Griffiths, and Sam Galbraith, the English, Welsh, and Scottish public health ministers have welcomed “It All Adds Up!” which has been launched with the slogan, “2f3m4”, a reference to the two or three unit limit for women and three to four limit for men. Tessa Jowell goes so far as to say, “This campaign is an excellent example of co-operation between the government and the private sector. Everyone needs to know where sensible drinking ends and serious health risks start. Everyone needs to know about when not to drink at all and about how very modest drinking can offer health benefits to certain age groups. The campaign is about spreading sensible information about sensible drinking. That is why I welcome and applaud it.”

The danger of the “sensible drinking” approach lies in the way the message is likely to be received. Indeed, when in December 1995 the then Secretary of State for Health, Stephen Dorrell, announced the new limits, which the Portman Group is now advocating, he was condemned in the press for issuing a “boozers’ charter”. To many the “sensible drinking” message is barely distinguishable from the promotion of drinking and so may have the perverse effect of encouraging the majority of moderate drinkers to consume more rather than persuading the minority of heavy drinkers to consume less. When the “sensible limits” were introduced by the last government, there was a tendency in the media to present them as a medically-approved target rather than as a maximum level and as safe limits rather than the risk thresholds they are intended to be. This problem will be exacerbated by the public health ministers’ approbation of what, in terms of the population average, are high levels of alcohol consumption and by the promotion of alcohol as a kind of health food which prolongs life, albeit within severely prescribed limits.

The green paper for England, Our Healthier Nation, presented to the House of Commons by the Secretary of State for Health, Frank Dobson, has only one paragraph on alcohol:

“Many people who drink alcohol enjoy it and cause no harm to themselves or others. Whether people drink sensibly can dramatically affect their physical and mental health and that of others. Drinking too much is an important factor in accidents and domestic violence and can impair people’s ability to cope with everyday life. It has been estimated that up to 40,000 deaths could be related to alcohol and in 1996 15 per cent of fatal road accidents involved alcohol. The government is preparing a new strategy on alcohol to set out a practical framework for a responsible approach.”

A consultation paper specifically on alcohol is expected in due course. Its possible contents may be guessed at from the more detailed section in the Scottish green paper, Working Together for a Healthier Scotland.

Labour ministers, and Dobson in particular, have been positioning themselves to steal a march on the Tories by portraying the Opposition as the advocates of the nanny state. Concern has been expressed that the tone of the paragraph on alcohol implies a watering-down of the Government’s attitude to the problem and the abandonment of the commitments set out in the Conservatives’ Health of the Nation, which included:

- health will be one of the factors taken into account by the Chancellor of the Exchequer in deciding alcohol duties.

- the commitment within the framework of the family health services to the promotion of the sensible drinking message will be strengthened.

- an agreed format for the display of customer information on alcohol units at point of sale will be considered jointly with the alcohol trade associations.

- there will be a new initiative to monitor the penetration of the sensible drinking message.

- continued encouragement will be given to employers to introduce workplace alcohol policies and to monitor their impact.

- the expansion and improvement of voluntary sector service provision.

The Health of the Nation also urged continued development of monitoring, screening, and treatment services at local level. The health professions were to be consulted in relation to the possibility of routine hospital admissions procedures including taking detailed drinking histories, and the government stated that it intended to pursue an initiative to heighten the awareness of nurses, midwives, and health visitors on the incidence of alcohol misuse.

The Health of the Nation set twenty seven health targets in the five areas of coronary heart disease and strokes, cancer, mental health, HIV/AIDS and sexual health, and accidents. However the trends ran counter to the targets related to drinking, smoking, and obesity. There has been no downward trend in the proportion of men drinking above “sensible limits” and the proportion of women drinking over the levels is increasing. ( See table above)

The Conservative Government’s alcohol targets were thrown into question in 1995 when it appeared to raise the “sensible” drinking limits. Although issued by the Department of Health, and although Stephen Dorrell, the Secretary of State at the time, had the opprobrium of the medical profession heaped on him, the work on the changes to the levels was co-ordinated by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food, which has a responsibility to promote the British drink industry. The limits were raised in defiance of the consensus of scientific opinion and under pressure from the industry’s poodle, the Portman Group.

Workers in the field of alcohol policy and treatment will have these, presumably redundant, targets in mind when the Labour Government produces its new strategy. The Department of Health is about to begin the process of consultation, aimed at producing this. It will be interesting to see whether the previous government’s inter-departmental ministerial group on alcohol misuse will be revived in some form.

In Our Healthier Nation, Frank Dobson says, “Far too many people are still falling ill and #dying sooner than they should…The Green Paper sets out our proposals for concerted action by the Government as a whole in partnership with local organisations, to improve people’s living conditions and health…We put forward specific targets for tackling some of the major killer diseases and proposals for local action.”

The green paper lays great stress on the health disadvantages of poverty and the social causes of ill heath. In his statement to the Commons, Mr Dobson said: “There are huge inequalities in our society, and the worst are in health. Poor people are ill more often and die sooner… Successive surveys have shown that over the past 20 years the gap between rich and poor has been growing. As a result, as recent official figures show, the health gap between rich and poor has also been growing.” This gap to which the Secretary of State referred is a result of a more rapid growth in good health among the better off. Mr Dobson went on to say, “The previous Government concentrated their attention exclusively on trying to get people to change their personal life styles, which sometimes needs to be done, but they ignored the factors that made people ill but were beyond the control of individuals.”

In his reply, John Maples, the Shadow Health Secretary, said that the World Health Organisation had “commended the (Conservative) Government’s strategy as ‘a model for others to follow.'” He acknowledged the connection between poor housing and bad health. “However, I believe that far more ill health is caused by smoking, the overuse of alcohol, bad diet, and lack of exercise…We must recognise that although some people are ill because they are poor, I suspect that there are many more who are poor because they are ill…getting people to improve their own life style is the key.”

Our Healthier Nation proposes targets for four priority areas:

- heart disease and stroke…

“reduce the death rate from heart disease and stroke and related illnesses amongst people under 65 years by at least a further third (33%).” - accidents…

“to reduce the rate of accidents…by at least a fifth (20%).” - cancer…

“to reduce the death rate from cancer amongst people aged under 65 years by at least a further fifth (20%).” - mental health…

“to reduce the death rate from suicide and undetermined injury by at least a further sixth (17%).”

It is suggested that the targets should be reached by 2010, from a baseline at 1996.

The Scottish Office Green Paper, Working Together for a Healthier Scotland, provides greater detail on alcohol policy. It may be an indicator of the direction of government thinking as far as the rest of the United Kingdom is concerned and, as such, the section is worth quoting in full:

“Over 90% of the adult population drink alcohol. It can be a part of a healthy lifestyle if taken in moderation and at the right time and place, and, indeed, there is evidence of physical health benefits of regular moderate alcohol consumption for men over 40 and women after the menopause. Both excessive consumption over long periods and heavy spasmodic drinking cause damage to health, accidents, and anti-social behaviour. The costs of alcohol misuse in personal, social and economic terms are great, and are all too often hidden or unheeded.

“Some 8% of men and 1% of women in Scotland – about 200,000 people – are drinking at levels which are definitely harmful. The 1994 General Household Survey showed alcohol consumption levels in Scotland to be broadly similar to those in other parts of the UK. There has been a greater tendency, however, towards binge drinking in Scotland and this may be the most significant variation in the patterns of alcohol consumption in the UK. Misuse of alcohol is a major risk factor associated with disease, homelessness, unemployment, criminality, mental breakdown, domestic violence and child abuse. Many working days are lost each year due to alcohol misuse. Heavy drinking contributes to high blood pressure, increases the chances of stroke, and is linked to cancer of the throat and mouth. A quarter of the men and a tenth of the women admitted to general hospitals will be problem drinkers. There has been a steady increase in deaths attributable to alcohol.

“According to the Office for National Statistics, there has been a small increase in the 1990s in the proportion of children in Scotland aged 12-15 who drink alcohol at all (from 59% in 1990 to 64% in 1996). However, there has been a more marked increase in the amount consumed by those who drink. The average number of units a week drunk by children of this age has more than doubled – from 0.8 units in 1990 to 1.9 units in 1996. Alcopops, which were first introduced into the market in 1995, accounted for about 18% of all alcohol consumed by this age group in 1996. Consumption by women has increased in the last two decades. Their smaller average physical size means that a given amount of alcohol may cause more damage to women than men.

“The target set for alcohol consumption was to reduce the 1986 figures for men drinking more than 21 units per week and for women drinking more than 14 units per week by 20% by the year 2000. The heavier the drinking above this level, the greater the hazard to physical and mental health. Findings from the Scottish Health Survey are that 33% of men and 13% of women drank more than these recommended levels. This indicates an increase compared with the 1986 levels of 24% and 7% respectively. To be effective, preventative policies have to focus on the moderately heavy drinkers as well as those at the extreme end of the range.

“The Government are fully committed to tackling alcohol misuse on a broad front. Alcohol development officers have been appointed throughout Scotland, co-ordinating action at local level. The licensing framework in Scotland works well and can react to particular problems, for example, licensing boards are required to refuse late night extensions unless satisfied of their community benefit. Regulation has recently been strengthened. Local authorities can now have recourse to byelaws prohibiting the consumption of alcohol in designated public areas. Under Scots law, it is already an offence for adults to buy alcohol for supply to children and recent legislation allows the police to confiscate alcohol from under 18s who are drinking in public.

“The Government have made clear that, if their current measures to bolster the action taken by the drinks industry towards better self-regulation do not bear fruit, they will take further action which could include legislation in areas which have traditionally been left to self-regulation. The Government have also made very clear their determination to tackle alcohol misuse by young people – which can lead not only to crime but also to under-achievement, poor health and poor employment prospects.

“A high proportion of adult fatalities from fire in dwellings (where the cause of fire was carelessness with smokers’ materials, pans left on cookers, or misuse of electrical apparatus, for example) has been linked with excessive intake of alcohol.

“In 1991, Health Education in Scotland: A National Policy Statement, set a national target of achieving a reduction of 20% by the year 2000 in the number of Scots drinking above the recommended sensible levels of 21 units a week for men and 14 for women.

“This target of 19% for men and 6% for women has not been reached and is unlikely to be by the year 2000. The Scottish Health Survey shows that a substantial proportion of the population -33% of men and 13% of women – is drinking in excess of the target limits, and the proportion doing so has increased sharply among both men and women since 1986. Given the large increase in excessive drinking in recent years and the widespread pattern of excessive drinking across social classes and across different regions within Scotland, the potential for reducing excessive alcohol consumption may be limited. This conclusion is supported by HEBS health survey findings, published in 1996, which show a motivation indicator (those drinkers aged 16-74 who want to or intend to cut down on their drinking) of only 6% for men and 4% for women. The main motivational barrier cited to moderating drinking was finding it difficult to cut down or stop when friends were drinking. The same survey showed that only 22% of heavy drinkers were taking action to change their behaviour: 49% were not even considering taking such action.

“The Government would welcome views on whether the current target for alcohol should be maintained and, if not, specific suggestions for alternative population indicators for alcohol misuse.

“The most recent guidance on alcohol consumption emphasised daily rather than weekly drinking levels. The recommendations are that regular drinking of 4 or more units a day for men, and 3 or more units a day for women is likely to result in increasing health risk.

“The Government would welcome views on this latest guidance, against the background of the previous weekly levels.

“Underage drinking is being viewed as a significant problem in its own right. The inclusion in future of young people’s alcohol consumption in the Scottish Health Survey will be of considerable benefit in this regard.

“Views would be welcome on setting a new target or indicator for underage drinking.”

The purpose of a Green Paper is to invite consultation. Our Healthier Nation and Working Together for a Healthier Scotland are obtainable from The Stationery Office Bookshops and priced £10.30p and £7.50p respectively. Responses should reach the Department of Health or the Scottish Office by 30th April.

Government crackdown on drunken yobs

A drive to reclaim town and city centres from drunken yobs who harass and intimidate families and law-abiding citizens was announced by Home Office Minister George Howarth.

Speaking in London to the Crime Concern Conference, Saturday Night Fever, Mr Howarth called on police, publicans, local authorities and magistrates to work in partnership with the Government to make towns and cities safer.

For some police forces alcohol-related violence and disorder is reported to be one of the most serious problems they face.

Research from the 1996 British Crime Survey suggests that about one in six violent incidents takes place in and around pubs – about 13,000 incidents a week.

Mr Howarth said:

“I want our towns and cities to be safe for everyone to enjoy. Partnership is the key to reclaiming the social and commercial hearts of our communities from the drunken yobs who have made them no-go areas. There are many excellent local initiatives where the police, publicans, magistrates and local authorities have taken effective action. I want to ensure that we build on those successes to win back our pubs and clubs.”

Two measures included in the Crime and Disorder Bill would help local authorities and police deal with alcohol-related crime and disorder.

They are:

- a new statutory requirement for local authorities and police to develop crime prevention partnerships, involving voluntary groups, business and local residents, to find local solutions to local problems like alcohol-related disorder;

- anti-social behaviour orders would allow local authorities and the police to seek a civil order from the courts to protect the community from individuals whose anti-social behaviour causes harassment, alarm or distress.

Mr Howarth welcomed action by the brewing industry to improve safety in pubs and clubs:

“Glassings cause thousands of injuries a year and the Government had made its concerns to the industry very clear. The industry initiative to make wider use of toughened glass will, I hope, make their use in pubs and clubs routine.”

Police and local authorities will also be encouraged to make full use of a whole range of legislation already on the statute books to deal with drunken anti-social behaviour. These include:

- the Confiscation of Alcohol (Young Persons) Act, brought into force last summer and designed to allow police to confiscate alcohol from underage drinkers who are creating disorder;

- pub exclusion orders, introduced in 1980 but little used, to ban offenders who have been found guilty of drunken violence in licensed premises;

- the Inebriates Act 1898 and the Licensing Act 1902 have been used by police in York to ban the sale of alcohol to habitual drunks;

- a model alcohol byelaw which local authorities can use to ban drinking in designated public places.

Local authorities and magistrates are able to attach conditions to new licences.

Mr Howarth told the conference that a ban on the sale of beer in bottles, which can be broken and used as weapons, could be made a condition of a licence in areas where there was a problem.

Scarred for life

The increase in the number of alcohol-related assaults in this country looks like continuing unless a serious effort is made to educate young people in the dangers of excessive drinking. This is the message of four oral and maxillofacial surgeons in The British Medical Journal.

Between 1977 and 1987 the number of patients requiring attention for maxillofacial fracture resulting from car accidents fell by 34 per cent. During the same time there was a 10 per cent increase in the proportion of injuries resulting from assaults. Since that time, there has been an increase of 77 per cent in violent crime of all types, whereas there has been a 38 per cent fall in deaths and injuries from road accidents.

From the data gathered in a survey carried out last September by the British Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, it is possible to estimate that half a million people suffer facial injuries every year, 125,000 of them in violent circumstances.

A great many of these assaults involve young people and in the majority of cases (61 per cent according to the survey) either the victim or the assailant had been drinking alcohol. Half the facial injuries sustained by people aged 15 to 25 were the result of assaults, nearly always in bars or in their immediate vicinity, and 40 per cent of these necessitated specialist maxillofacial surgery.

Writing in the BMJ, the four surgeons* state that “other countries with similar alcohol consumption figures have not experienced such an epidemic of assaults in young people. Brief interventions to tackle alcohol misuse in the aftermath of injury are both effective and valued by patients.” In an attempt to alert young people to the risks of facial injury as a consequence of drinking and fighting, 200 oral and maxillofacial surgeons recently visited secondary schools throughout the country. It will be important to study the effects of this intervention.

The survey by the British Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons indicated that, whereas “four times more men than women sustained facial injuries in assaults, in the home the reverse was true.” The survey demonstrated the alarming fact that nearly “half of all facial injuries sustained in assaults on women occurred in the home, presumably by members of the immediate family, and almost half these were associated with alcohol consumption by the victim or assailant.”

It is an inescapable conclusion that alcohol drinking and assault are the “major factors responsible for serious facial injuries in young adults.” It is interesting to note that “the effect of alcohol in increasing vulnerability to injury may be more important than its effect on aggression.” The surgeons conclude that “the most beneficial strategy may be to target 13-14 year olds and educate them about the dangers of excessive alcohol consumption and its association with assaults and road accidents.”

Intoxicated with words

As a young man with literary pretensions loose in London in the early seventies, I frequently came across a curious sub-group of saloon-bar bore. In almost every pub in Soho, Bloomsbury, and Fitzrovia there was The Man Who Lent Dylan Thomas a Fiver. Just as Elizabeth I must have changed beds every night of her life and Mary, Queen of Scots, dragged a library onto the scaffold, Thomas must have died a very rich man. Such is the power of myth.

Literary giants – and even poets and novelists slightly above average height – attract myth, especially, it seems, when they do things to excess. As they tend to be obsessive characters, this is often the case. Prodigious feats of drinking and fornication – activities mutually exclusive only if attempted simultaneously – are attributed to them. Many have a basis in reality. Tales grow in the telling. If you got drunk with Hemingway and lived to tell the story, then some of the heroics you report rubs off, especially if you carried him home. ‘Heroics’ seems to be the right word for the way the abusive drinking of famous writers is recorded. Not that total unknowns are marked out by their sobriety: for every Nobel prizewinner sustaining his self-image with the whisky bottle, there is the drunk who would have written the novel of the century had he just got round to it or if the philistine conspiracy of publishers had not thwarted him (thank God!).

Let us get one thing straight right away: nobody ever wrote better stuff because they were drunk. There are, of course, thousands who will tell you differently, just as there are still those sad characters who insist that a few drinks improve their driving or performance in bed or family life. This is called denial. It may well be that, in the brief period when inhibitions are relaxed by alcohol, inspiration seems to come, in the same way that a youth, emboldened by a couple of beers, gains the courage to talk to an attractive girl. More alcohol is consumed and drivel pours onto the page like vomit onto the girl’s lap. But so many great writers, and not just the chronic alcoholics amongst them, say that booze helps them compose. Why? Because it seems to. There is interesting research being done which suggests that, to some degree, drunken behaviour is learned or conditioned by circumstance. Stone-cold sober, the writer looks at the empty page; he takes a drink and something happens which triggers an idea. There was a chess grand master who claimed that, if stuck, he would leave the table, drink a glass of brandy, and return with a solution to the problem. Was it the brandy itself that stimulated him or was it because he believed it would do so? I offer no easy answer, merely the unhelpful observation that alcohol is cunning, powerful, and baffling. Like the weird sisters in Macbeth, it appears to be a useful tool in making you believe what you want to believe.

Simone de Beauvoir, says John Booth in the Introduction toCreative Spirits: A Toast to Literary Drinkers, “claimed that intoxication breaks down the controls and defences that normally protect people against unpalatable truths, forcing them to face reality.” De Beauvoir began the day with vodka and moved on to scotch, Johnny Walker Red Label, Mr Booth tells us. This might be a sensible move for someone in love with Jean-Paul Sartre, but it is bizarre to see it as a gateway to reality. Existentialist to the end, she refused to moderate her intake when experiencing death from cirrhosis of the liver. Anyone at Mlle de Beauvoir’s level of dependency has no freedom of choice. She was a wonderful writer but, like all drunks, said some very silly things. And it was an act of barbarism on her part to keep whisky in the fridge.

John Booth had a good idea when he sat down to write. The book contains a lot of amusing anecdotes, but it falls between a number of stools and is curiously mealy-mouthed. Stools first. There are writers who drink a lot, there are writers who write about drink, and there are alcoholic writers. It is as well to differentiate but Mr Booth blurs the distinctions, much as booze blurred the talent of, say, Ernest Hemingway. There is room in a volume about literary drinkers for both Brendan Behan and Ronald Tolkien but the reader should not be left with the impression that we are talking about different ends of the scale. The same thing was not happening. A convivial evening in an Oxford pub, chuckling at dirty jokes in Old Norse, is one thing, drinking to oblivion, by way of a few punch-ups in McDaid’s bar, a stopover on the road to an early grave, is quite another.

This would be a better book if the nature of different writers’ drinking, and the consequences for his work, were discussed. It is easy to condemn a book for not being the one you would have written yourself, but the point is important. Mr Booth himself stresses how central alcohol has been in the creation of literature: “It is surely unarguable that drink has been as powerful an influence on creative writing as love, philosophy, desire for fame or any other form of inspiration.” Having made this deeply depressing statement, he proceeds to be mealy-mouthed. It is interesting to look at instances of fine writing about alcohol. Just like cricket, sexual intercourse, and politics it has inspired some good prose, but, again like them, it had produced a lot of embarrassing tosh. Nowhere in the book does Mr Booth look at the detrimental effects of lcohol on literature. He seems to think that even when Thomas is vomiting, Behan fighting, or Hemingway making life a misery for those around him, literature is being served. Nowhere does he consider the possibility that avoidance of alcohol might have greatly improved some writers’ output. The worst excesses of drunken writers are treated as a kind of naughtiness, excusable because of their artistic nature and because many of them contrived to be amusing at some stage of intoxication. The author is as reticent about the grosser effects of alcohol as he is about the fact that de Maupassant “suffered from his enthusiasm for women.” Good God! the man was confined to an asylum with syphilitic dementia.

Mr Booth’s choice of quotation is odd. He includes the scene from Brideshead Revisited where Charles and Sebastian make themselves free of Lord Marchmain’s cellar. Waugh is a great writer whose work abounds in passages about drink and its effects, both happy and baleful. It seems a pity that the only example we get is the one of tiresome undergraduate affectation, however tongue in cheek the young men are being. The principal interest in Waugh’s portrait of Sebastian Flyte is his descent into alcoholism. Carefree drunkenness, largely indistinguishable from that of his fellows, changes into solitary and morose drinking. His emotional turmoil and dysfunctional family are delineated with consummate skill and subtlety by Waugh and is probably one of the bleakest descriptions of dependency in literature. Only his faith, frail though it is, saves Sebastian from ultimate despair, the deadliest sin. Mr Booth does Evelyn Waugh a disservice in selecting this particular passage, but it is in line with his view that the inevitable horror of abusive drinking be excluded from the book. But Mr Booth does not know much about Waugh (nor, for that matter, the meanings of the words ‘boor’ and ‘snob’). He says: “A lifetime of heavy drinking does not seem to have ruined his palate or affected his appreciation of wine.” In the last decade of his life, Waugh sold his large cellar of clarets because he was no longer able to enjoy their taste.

It is difficult to avoid the suspicion, perhaps harsh, that not a lot of research went into Creative Spirits. Some of the extracts chosen for inclusion read like they were selected from memory during a good lunch. “Isn’t there a bit in Brideshead where the narrator and whatsisname learn about wines?” “Omar Khayyam’s got plenty of bits about booze.” “How about Gibbon on German beer drinking?” I am all for Horace but not sure why he is quoted so extensively or to what end. It is a kindness, however, not to identify his translator.

If the quotations tend to be idiosyncratic, the choice of anecdote occasionally defies understanding. Behan said a lot of funny things, so why embarrass his memory with the feeble joke he allegedly made when asked the purpose of his visit by a Canadian immigration official? “To drink Canada Dry”, a witticism which must have been coined moments after the advertising slogan was first suggested. Speaking of jokes, to remark that “(Housman) was a classic don” is to commit a pun best left to schoolmasters in the privacy of their own classrooms.

When, as Prince of Wales, Edward VII appeared in the witness box over the Tranby Croft Affair, he roundly condemned gambling as a curse of the lower orders. He did concede that a gentleman might have the occasional wager. The same attitude is often applied to alcohol (Dr Stuttaford of The Times , in his recent book on the joys of booze, says that the effects of abusive drinking are felt in the pokey homes of the poor whereas they might be avoided with ancestral halls to roll about in – see Alert, December, 1997). The implication is here in Mr Booth’s book. In L’Assommoir, Zola paints a vivid picture of the horrible results of drunkenness in the sordid bars of the slums. Degas’ L’ Absinthe (opposite) captures the scene. Contrasted to this, but with no particular irony, are the lavish dinners given by Zola to his literary circle when there were seven glasses to a guest. De Goncourt may have gently mocked these occasions in his diary, but no doubt he relished each wine whilst joining his host in deprecating the effects of rot-gut among the proletariat.

This is really the problem with the book. It fails to get to grips with the subject. I do not mean that it should have been a mean-spirited polemic against the evils of drink, I simply mean that it should have given a more accurate account of the effects of alcohol on literature. Behan, Thomas, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, countless lesser figures, died sordid deaths after destroying their talent. “Living out a legend”, as Mr Booth describes Dylan Thomas, sounds attractive, alcoholic incontinence does not, and the purpose of the book seems to be to romanticise the drunken author, in effect, to enshrine the myth.

This book has some amusement value, but the feeling is always there that it should have been much funnier. There are no insights which will help the reader better understand the work of the writers mentioned . It would have been useful if the book had got the message across that a writer with a skinful is no more admirable than a football fan in his cups and about as creative, but the sad thing is that an impressionable young person with the ambition to earn a living by his pen will put down Creative Spirits with the suspicion that it would help to be a drunk. One or two might make it, the rest will be found in The Coach and Horses, thinking up ideas for potboilers and telling the story of how they borrowed a tenner from Martin Amis.

Andrew Varley

The drinking doctors problem

Two thirds of cases referred to the General Medical Council are related to doctors’ misuse of alcohol and other drugs, according to the British Medical Association’s recent report on The Misuse of Alcohol and Other Drugs by Doctors. The fact that so many doctors’ problems lead them into GMC disciplinary procedures seems to indicate that, more often than not, matters reach crisis point before action is taken. This is partly because doctors “are reluctant to seek help due to the stigma attached to psychological illness, in particular substance misuse, and the professional risks associated with acknowledgement of this.”

The report’s aims are:

- to support the paramount need to prevent any risk to the welfare of patients from impaired professional competence;

- to raise awareness of the nature, extent, complexity, and consequences of misuse of alcohol and other drugs occurring among doctors;

- to highlight the need for education on the manifestation and presentation of drug and alcohol misuse including the frequent occurrence of denial and avoidance of treatment;

- to ensure access to appropriate services for examination, diagnosis, and referral for treatment and to guide affected doctors towards treatment facilities;

- to highlight the need for long term rehabilitation, which may include retraining for reentry into the medical work force.

Another problem is that a large proportion of doctors is unaware of the range of services available. This is confirmed by those working in the field of rehabilitation, either in clinics or counselling practices. It is also the case that many doctors have observed “the lack of support provided for colleagues with similar problems.” At the same time misplaced loyalty often prevents doctors intervening when they see others with a drug abuse problem.

As with the wider population, there is a perception that the problem largely affects males. In the medical world it is also seen as being more common amongst those past the mid-point of their careers and amongst general practitioners. On the other hand, those units which specialise in the treatment of doctors state that doctors of both sexes are affected, from those just out of medical school to those in retirement, and covering the whole range of the profession, GPs, those in hospital medicine, and those in the private sector.

The report makes the point that no strict division can be made between alcohol and other drugs where doctors are concerned. “Doctors who misuse alcohol are often at the same time involved in misuse of other drugs, most commonly benzodiapezines, and they may switch between one type of substance and another over time.”

Among the main recommendations of the report are that the “recognition and management of drug and alcohol addiction must be highlighted in undergraduate, postgraduate, and continuing education programmes for doctors and all health care professionals”; active measures for the rehabilitation of addicted doctors and their retention in the profession once in recovery need to be taken; that there should be support available for those “who express concern about a colleague”, especially those doctors who are still in training grades; that every medical school should have a drug and alcohol policy covering a wide range of issues, including permissible drinking times, services available to those with problems, and sensible drinking advice; and that doctors should avoid self-prescribing. The recommendations are directed, as appropriate, to the GMC, NHS Trusts and Health Authorities, the NHS Executive, the Department of Health, and the Association of Chief Police Officers.

In an editorial which discusses the report, the British Medical Journal says: “The phenomenon of the addicted doctor may shock and offend. Nevertheless, it must be addressed by both the profession and employers as an important cause of impaired performance through ill health. In America, state level ‘impaired physician’ schemes ensure that addicted doctors are confronted, receive adequate treatment, and return to work under supervision…The BMA report illustrates [that] greater professional awareness at all levels and visible dedicated services will enable many doctors to avoid the tragic consequences of drug and alcohol dependence that can so effect their patients, their family, and their careers. The current lack of a dedicated service leaves many addicted doctors unchallenged, untreated, and abandoned: the BMA report’s failure to deal with comment on this point is an important shortcoming of an otherwise excellent document.”

If the estimate of 9,000 doctors (one in fifteen) with an alcohol or other drug problem is correct, then the issues highlighted by the report need to be addressed as a matter of urgency. It is clear that too few doctors are aware of what is available, or indeed possible, in drug and alcohol treatment either for their patients or themselves.

The old joke that a problem is indicated when a patient drinks as much as his doctor is no longer funny, if it ever was.

The case of the well-oiled skipper…

A 57 year old man was referred to an outpatient department. He was late for his appointment because he had crashed his car in the hospital car park. He was anaemic and showed signs of chronic liver disease. The following morning he was admitted, smelling strongly of alcohol, for a blood transfusion. He expressed his desire for an early discharge so that he could return to his duties as captain of an oil tanker.

This case, and others like it, generated a lively debate as to what action doctors should take when faced with patients who are obviously abusing alcohol and prompted Dr Roger Barton, of the Academic Department, North Tyneside Hospital, to carry out a survey on the subject which is reported in the British Medical Journal of 15th November.

Dr Barton and his assistant, Ruth Dale, sent a questionnaire to 400 GPs and hospital physicians in the former Northern region. Out of 240 replies, 32 doctors (14 per cent) said they would not ask their patients to inform the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) and 33 (16 per cent) would not ask them to inform their employer. 68 (31 per cent) and 95 (46 per cent) would not check compliance. Dr Barton and Miss Dale point out that in up to 45 per cent and 62 per cent of cases the licensing agency and employer might remain ignorant of the potential danger.

The survey found that “general practitioners were more likely than hospital doctors to ask the patient to inform the licensing agency and employer, to check compliance, to ask a defence society’s advice, and to discuss the problem with a colleague.

The actions taken by doctors would vary considerably, despite there being clear guidelines from the DVLC: “Medical practitioners may be failing in their duty of care if they do not alert their patients to the need to notify the Licensing Centre… Since many problem drinkers will not themselves notify the licensing agency, the doctor sometimes should do if he feels the public are at risk.”

The code issued by the General Medical Council says doctors should “explain to patients that they have a legal duty to inform the DVLA. If the patient refuses to accept the diagnosis or the effect of the condition you can suggest that the patients seek a second opinion. You should advise the patients not to drive until the second opinion has been obtained. If patients continue to drive…you should make every reasonable effort to persuade them to stop. This may involve telling their next of kin. If you do not manage to persuade patients to stop driving, or you are given or find evidence that a patient is continuing to drive contrary to advice, you should disclose relevant medical information immediately, in confidence, to the medical advisor at the DVLA. Before giving information to the DVLA you should inform the patient of your decision to do so. Once the DVLA has been informed, you should also write to the patient, to confirm that a disclosure has been made.”

As regards patients whose work is hazardous or could cause harm to others, such as the tanker skipper, the GMC guidelines state that “disclosures [of information about patients] may be necessary in the public interest where failure to disclose information may expose the patient, or others, to risk of death or serious harm. In such circumstances you should disclose information promptly to an appropriate authority.”

Professor Jonathan Shepherd, of the University of Wales College of Medicine, in the same issue of the British Medical Journal, says, “The implications of the General Medical Council’s guidance may not yet have been understood fully by many doctors. It emphasises doctors’ wider responsibilities.”

The legal situation is not straightforward. Doctors have a legal duty to maintain confidentiality but this duty is not absolute. Obviously, a doctor may disclose information to a third party if the patient consents. In addition, it is a defence in law that disclosure to a third party is in the public interest. What exactly this defence covers is at the moment decided in the courts case by case. There is no doubt, however, that the defence includes the disclosure to the DVLA or an employer of a patient’s alcohol abuse in order to prevent injury to others. Public safety, in this case, outweighs the patient’s right to confidentiality.

Another legal question is whether a doctor is susceptible to a charge of negligence if he fails to disclose information about a patient to the relevant authority and that patient subsequently injures someone. It is usual in English and American law to assume that there is no “duty of care” to take action to prevent someone injuring another. At present, this looks like remaining the case.

Deborah Brooke, a consultant in forensic psychiatry at Bexley Hospital, makes the point, when discussing the results of Dr Barton’s survey, that “almost a third of medical and surgical admissions to hospital are for problems related to alcohol, and the profession has been poor at detecting and addressing these problems. A main cause is insufficient training and in recognising and treating substance misuse at undergraduate and postgraduate levels.

Dr Brooke says that the results of so many doctors being ill-equipped to deal with the problem – “uncertainty about management, accompanied by gloomy prognostications” – has led to the neglect of alcohol problems amongst colleagues in the medical profession. The GMC has made it clear that it is unethical for a doctor to fail to disclose information about a colleague whose abuse of alcohol is putting patients at risk.

Brown looks both ways and stays where he is

Despite the automatic cries of “Foul!” from the industry, the Chancellor has in effect left the alcohol question on hold. He could have gone either of two ways. In order to combat the considerable problem of cross-channel smuggling, he might have taken the bold step of slashing duty as demanded by the industry. On the other hand, he had the opportunity of listening to the public health lobby and imposing increases which would have had a real effect on consumption. He has chosen to temporise.

The argument that tax increases have a direct impact on public health and the environment is accepted in the cases of tobacco and petrol, but not when it comes to alcohol, is the clear implication of Gordon Brown’s budget. Whilst a swingeing 20p was added to the price of a packet of cigarettes, beer escaped with 1p a pint, wine with 4p a bottle, and for spirits there was no increase at all. In other words, the Chancellor has done no more than keep any alcohol price rises in line with inflation and these will not come into effect until 1st January, 1999.

The increases which will occur are:

- Pint of beer +1p

- 75cl bottle of table wine +4p

- litre bottle of cider +1p

- 33cl bottle of alcopop +1p

- 70cl bottle of fortified wine +5p

At the same time, 36p has been knocked off the price of a bottle of low-strength sparkling wine as a result of a 20 per cent reduction in duty. There was, however, a 20 per cent increase in the duty paid on sparkling cider or perry – 9p on a litre bottle. These measures follow complaints from Brussels that the mainly domestically produced sparkling cider enjoyed an advantage over the largely imported wine.

The decision to leave the duty on spirits unchanged was taken in order to help UK producers and exporters. The Scotch Whisky Association, a powerful force north of the border where the Labour Party feels threatened by the growth in SNP popularity in the run up to the establishment of a Scottish Assembly, was understandably pleased at having escaped any increase.

Others in the drinks industry were not so happy. The Chairman of the Wines and Spirits Association, Dr Barry Sutton, claimed that Gordon Brown had produced a “crime-boosting budget.” Dr Sutton added, “Increasing taxes on wine will further encourage organised crime without any real benefit for UK taxpayers.” (sic) The chief executive of Diageo, the newly-formed largest drinks group in the world, said, “We are pleased that the Chancellor has at last recognised the need to reduce the level of tax discrimination against spirits… However, the budget increase on beer is a detrimental one for the beer and pub sector and will serve to increase cross-border smuggling.” This last point was echoed by The Brewers and Licensed Retailers’ Association: “This is bad news for thousands of pubs and good news for the beer smuggler.” The Campaign for Real Ale (Camra) stated that the duty increase on beer will mean 2p on a pint over the bar when brewers’ profit margins are taken into consideration.

Alcohol Concern was pleased with the increased duty on beer. A spokesman said that “any cut in duty would be damaging. And before brewers and pubs expect the Chancellor to bail them out, we think they should take a lead and trim their own margins. The bulk of disparity in prices between the UK and France does not come from excise duties.”

However, others concerned with alcohol policy may note that despite the government’s tough talk about alcopops and the setting up of a ministerial group, Gordon Brown, in his two budgets, has raised the excise duty on these products by a mere two pence. In 1996 Ken Clark, the then Tory Chancellor, froze the duties on beer and wine and took 26p a bottle off spirits, but imposed a 40 per cent increase on the duty on alcopops, the equivalent of 7/8p. This increase was clearly a response to the pressure “to do something” about under-age drinking in general and alcopops in particular.

The rise of 20p on a packet of cigarettes was not welcomed unequivocally by anti-smoking organisations. Clive Bates, the Director of ASH, whilst estimating that the measure would save 2,000 lives a year, was “very unhappy with the fact that the increase would not come in until December 1st.” Much happier were French supermarket managers near the Channel ports. They estimate that their trade in cigarettes has increased by 600-700 per cent since the last increases and see no reason to doubt that this budget will encourage the trend.

According to official figures, the Treasury is losing £690 million every year because of tobacco smuggling. The Tobacco Manufacturers Association believes that the true figure is nearer £2 billion. The Wine and Spirits Association says that alcohol smuggling is costing another £500 million.

The industry believes that one in five pints of beer is being imported from France. Camra has stated that 13 per cent of the beer produced in France goes to UK customers and that 1.4 million pints are imported every day which amounts to the weekly sales of 2,000 pubs.

Taxing time for brewers

The legal arguments put forward by Shepherd Neame, the Kent brewers, against the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s imposition of a penny a pint increase in the price of beer failed to impress at the first stage of the process. Lord Justice May and Mr Justice Moses, sitting in the High Court, refused the company’s application to have the matter referred to the European Court of Justice. Lawyers for the brewery claimed that the duty increase announced in the July budget was incompatible with European community law.

The Financial Secretary to the Treasury, Dawn Primarolo, said, “This decision upholds the important principle that parliament can legitimately set excise duties in the UK, subject to minimum rates agreed with our EU partners. Customs and Excise will continue to collect beer duty at the new rate.”

However, the next stage of the legal procedure is a full hearing at the Court of Appeal. This was allowed by the Vice-Chancellor, Sir Richard Scott, at a very brief hearing on 20th March, without Shepherd Neame’s counsel having to say anything. The brewer’s legal team is led by Cherie Blair, QC. Stuart Neame, the vice-chairman of the company, said, “The fact that she is the Prime Minister’s wife has nothing to do with her as the choice to fight the government over their rate of tax on beer. But the irony is not lost on me.”

The brewery hoped that the raising of the tax on beer would be ruled a breach of European law which requires member countries to harmonise duties across the Union. The possibility now exists that the Court of Appeal will allow the case to proceed to the European Court.

Shepherd Neame declared that the government’s decision to put a penny on a pint was “a threat to British beer.” Reacting to the original High Court judgement, Stuart Neame warned that “hundreds, if not thousands, of pubs could be closed.” As Shepherd Neame control 374 pubs themselves, this could be bad news. The brewery claims that 1.4 million pints of beer enter this country through Dover every day. Shepherd Neame also believe that one third of the pints drunk in Kent come from the continent. They have already closed 45 pubs since the introduction of the single European market, but do not say what other factors were involved. Top stockbroker, Merrill Lynch, point out that the capital expenditure of the ten leading pub companies runs at 78 per cent of their operating profit. This reflects the huge amounts being spent on refurbishing and restyling of pubs to meet what is perceived as market demand. This is part of the restructuring of these companies which sees larger profits in bigger new pubs, a move which inevitably results in the closure of smaller outlets.

The alcohol industry has been energetic in its drive to secure concessions and assistance from successive governments. However, its blandishments have cut less ice at the Treasury since it lowered excise duties on scotch whisky and saw the distillers not only fail to pass on the benefits to consumers but actually raise their prices.

Gales of derisive laughter

Researchers at the University of Hull have been working on “Effects of Alcohol on Responsive Laughter and Amusement” and their findings “provide empirical support for the commonly held notion that drinking increases frequency of laughter and humour.” Notions are often commonly held because they are self-evident to any reasonably sentient being, but it is good that the academics of Hull have found time to confirm the obvious.

Anyone observing a party in progress will see that the volume and frequency of laughter grows with the intake of alcohol. It is doubtful, however, that there has been any parallel increase in humour. An abstemious observer is much more likely to note that, in these circumstances, the laughter is in inverse proportion to the humour. Wit and allusion require some clarity of thought to achieve a response. It is an occasional topic of debate amongst actors as to how drunk an audience needs to be to give an adequate response to a funny play. Obviously, the level varies. Very little would suffice for a Wilde, a Coward, or an Aykbourn; less subtle authors might require a larger intake. It is surprising what dire material a comic can get away with when faced with a drunken audience but the down side, of course, is the grave risk of over enthusiastic participation.

As alcohol removes the ability to discriminate, bad jokes arouse totally disproportionate mirth (the Researchers of Hull must forgive the lack of empirical back-up for this truism). Responses to sentimentality and irritation may well be the same: what is merely embarrassing when stone-cold sober, provokes tears after a few drinks; what is shrugged off as boorishness, becomes the cause of a violent dispute. There is more fruitful research to be done, University of Hull.

The researchers point out that “the use of humour and laughter has been found to correlate with good physical health”. So the Lewis Carol syllogism runs, “Laughter makes me live longer. Alcohol makes me laugh. Therefore, alcohol makes me live longer.” Quod erat demonstrandum.

They must have an impressive longevity at the University of Hull.

lifetime abstinence, long term health

The view that higher rates of morbidity among non-drinkers is largely accounted for by pre-existing ill health and the age distribution of the group is given support by the recently published General Household Survey Report.

The prevalence of long standing illness was higher among non-drinkers and those who drank one unit of alcohol or less per week. However, among the non-drinkers, 52% of men and 58% of women were lifetime abstainers, while 48% of men and 42% of women had stopped drinking. Age-standardised figures show that the prevalence of longstanding illness among men who were lifetime abstainers was no different from what would be expected given the age distribution of the group. There was, however, an exception with women lifelong abstainers.

Men and women who stop drinking for health reasons were the most likely to have a longstanding illness. Differences were less marked for the prevalence of acute illness or those who experienced restricted activity within 14 days prior to the interview. Although those who had stopped drinking for any reason were significantly more likely to report an acute illness.

Reasons for non-drinking among lifetime abstainers (men and women) were religious – 40% and 22% and don’t like it – 39% and 57%.

The report also shows that men and women in the highest household income group (more than £500 gross per week, were more likely to exceed 21 or 14 units – 34% of men and 20% of women compared with 14% to 27% of men and 9% to 14% of women in other income groups. The proportion of non-drinkers was higher in lower income groups – 13% of men and 20% of women where the gross weekly income was between £100 to £150 compared with 3% of men and 7% of women in the higher income group.

Thousands call Drinkline

6,000 people a month have called Drinkline since it was founded in 1993. Following the established practice of Alcoholics Anonymous and Al-Anon, the organisation has sought to help problem drinkers, or those concerned about a problem drinker, by means of its telephone network. The helpline is staffed by trained counsellors.

A profile of callers shows that 59 per cent were seeking help for themselves and 37 per cent were concerned about others. Just over half of the callers who were worried about their own drinking were women which is in contrast to the proportions of men and women presenting at rehabilitation clinics or specialist counselling practices. This may well reflect the greater embarrassment generally felt by women in admitting to a drink problem and the attraction of anonymity. 76 per cent of those who called on behalf of another person were women.

The slight majority of callers were seeking help with a drink problem for the first time. Most of the rest had previously been to AA, a local alcohol agency, or a GP. This pattern of contacting a variety of sources of help is not unusual among problem drinkers and tends to indicate a hesitancy about accepting the necessity of change. It may also be part of a search for the answer the drinker wants to hear, quite often that it is all right to continue drinking in a controlled way. The uncompromisingly abstinent message of AA does not appeal to such drinkers.

When someone calls Drinkline, he is given “factual information about safe drinking levels, advice, and guidance about ways to control, or avoid alcohol and practical suggestions about overcoming any related problems.” The survey of users shows overwhelming appreciation of the service Drinkline offers. 81 per cent said that they “were given all the information and advice they needed at the time.”

Of course, there are limitations to what telephone counselling can achieve. A leading alcohol therapist said, “Telephone counselling can be effective in short, emergency interventions but, of course, difficulties of engagement and honesty are bound to arise.”

91 per cent of the sample intended to carry out some kind of plan of action as a result of calling Drinkline. It is significant that the highest level of resolve to do something was found among those admitting to the largest alcohol consumption. “Just over two thirds of concerned others reported that their concerns had lessened or reduced in the two months after calling Drinkline.” This occurred either because, among those with a minor problem, the contact with Drinkline had alleviated matters or because referrals had led to treatment, detoxification, or participation in a 12-step programme.

Given the nature of its activities, Drinkline makes no claim to a direct connexion between itself and any subsequent changes in the lives of its clients. It is undoubtedly the case, however, that Drinkline has played a very important part in the process of seeking change. It has acted as a catalyst to further action on the part of the callers. At the very least, the opportunity of talking on the telephone can provide comfort, at best it can lead to the road to recovery and an end to the suffering of the problem drinkers and those close to them.

Code of practice for courts

The Magistrates’ Association and the Justices’ Clerks Society, want to see much stiffer penalties for selling alcohol to under-age drinkers. In response to widespread concern about the problem of under-age drinking and unlawful sales to minors, have published a Code of Practice for use in the courts. Ironically, this occurs just as the David Knowles case reveals a disturbing loophole in the law.

The main points are:

- There is concern that the current maximum penalty for offences involving breach of licensing laws is inadequate. Courts accept that they must apply the law as it stands not as they would like it to be. However people who deliberately or recklessly flout the law in relation to illegal sales of alcohol must believe that, if caught, the sanctions will be substantial.

- It is recommended that courts consider a substantial penalty for any person convicted of an offence involving sales of alcohol to persons underage. A similar penalty should apply to anyone convicted of buying alcohol in on-licenced premises on behalf of an underage person.

- It is recommended that all courts make arrangements to ensure that convictions of licensees are brought to the attention of the licensing committee to enable the committee to examine the circumstances of the offence and decide whether it is so serious that revocation of the licence is justified.

- Section 169(8) of the Licensing Act 1964 allows a bench to order the forfeiture of a justices’ licence if the licensee has been convicted for the second time of an offence involving the sale of intoxicating liquor to, or for consumption, by a person under 18. There is no requirement for a referral to the licensing justices for such an order of forfeiture to be made. Courts need to examine the circumstances in which young offenders obtained access to alcohol and decide whether this could have been prevented by proper parental care.

Where offenders before the youth court have committed offences under the influence of drink, their parents should be bound over to take proper care of them, if it is clear from the circumstances that the parents ought to have been concerned about their child’s whereabouts.

Those responsible for framing this code and administering the law should be aware of the case of the tragic death of fourteen year old David Knowles and the shocking legal loophole which allowed the people who sold him alcohol to escape prosecution…

The David Knowles Case

David Knowles was 14 when he was killed running over a major road near his home in Pudsey. Immediately before his reckless and final act, he had consumed three cans of lager. On his way home with some friends from football practice, David passed a Threshers off-licence called the Drink Cabin. The other boys in the group asked David, who was the only one not in football strip, to go in an buy the bottles of the alcopop, Hooch. Having done this, he decided that he too would like an alcoholic drink, returned to the same off-licence, and bought four cans of lager. His friends subsequently reported that as they walked along David drank three of the cans.

Their path took them next to the Leeds ring road, a heavily used dual carriageway. David’s friends say that at this point, without any warning or explanation, he shouted out, “Let’s run!”, jumped over the fence, and dashed down the embankment. He ran straight across one carriageway, crossed the central reservation, and, in negotiating the second carriageway, was struck by an oncoming vehicle. He received major injuries from which he subsequently died.

The police were quickly on the scene and took statements from witnesses. They then went to the Threshers off-licence and seized the security video which showed fourteen year old David being served alcohol on the two separate occasions by different members of staff. On the basis of this evidence and the statements which had been taken, the Crown Prosecution Service decided to press charges against the two Threshers employees.

The prosecution could not go ahead because counsel’s opinion, sought by the Director of Public Prosecutions, was that it would fail because of precedents set by the appeal Russell versus the Director of Public Prosecutions (1997) and other cases dating from 1968 and 1996. Russell v. DPP confirmed that people selling alcohol to persons under 18 can be found guilty under Section 169 (1) of the relevant Act if they are the licensee or the directly employed servant of the licensee. However, in Russell v. DDP, it was stated that “a trainee branch manager employed by a limited company was not a ‘servant’ of the licensee… but a ‘servant’ of the employing company for the purposes of Section 169.”

In the case of David Knowles, the persons who sold him the lager were employed by a national off-licence chain and not by the licensee whose name appeared above the door of their temporary place of work. This technicality served as immunity from prosecution.

John Knowles, David’s father, looked for help to Paul Truswell, the Member for Pudsey who put down an Early Day Motion drawing the attention of parliament to this alarming loophole in the law. Only 36 members of the House of Commons have so far seen fit to sign it. Mr Truswell continues his commendable efforts to persuade his fellow parliamentarians to support him. He said, “The Licensing Act of 1964 was framed when national off-licence chains and supermarket sales of alcohol lay in the future. This situation was not foreseen and must now be remedied.”

Mr Truswell has presented a petition to the House of Commons, signed by 1200 of his constituents, requesting Parliament “amend the Licensing Act of 1964 to correct this major defect in the law which no longer provides the protection to people under 18 originally intended.” He has also had meetings with George Howarth, the Home Office minister responsible for licensing, who has instructed his legal advisers to scrutinize the case. They will decide whether there is indeed a loophole or whether there has been a misinterpretation of the law. Paul Truswell believes it is 99.9 per cent certain that the loophole exists. When this is confirmed it will be necessary to find a way to remedy the situation by an amendment or new legislation.

Given the fact that the law was recently altered to allow under 18 year olds under the apprenticeship scheme to serve in bars and off-licences, it looks as though a youth of 16, employed as a trainee by a central organisation, may sell alcohol to a child without fear of prosecution. It is a loophole which will hang more young people if it is not closed swiftly.

Drug Tsar lays his plans

£50 million has been allocated by the government to take the anti-drug message to children and to deal with addicted prisoners. These measures are part of the strategy which Keith Hellawell will announce this spring. Mr Hellawell, the former Chief Constable of West Yorkshire, was appointed ‘Drugs Tsar’ by the Prime Minister in October, 1997.

A nationwide education programme for primary schools has already been shown to government ministers. Children as young as six will be targeted in an effort to establish resistance to the temptation to use drugs. In gaols, the intention is to isolate persistent drugs offenders from those who wish to tackle their addiction. Mr Hellawell’s deputy (Tsarevitch?), Mike Trace, came to his post from RAPT, the Rehabilitation of Addicted Prisoners Trust, where he was Director. He has wide experience of working with prisoners to help them kick the drug habit and, it is hoped, avoid the crimes which, in many cases, were necessary to finance addiction. Compulsory drug testing and treatment are proposed for anyone who falls into this category.

One of the main priorities of Mr Hellawell and his team will be to influence children before they have been exposed to the blandishments of the so-called drug culture. The Drug Prevention Unit of the Home Office has found that children given weekly classes in the danger of drugs are markedly less likely to become users when they reach their teens. This is a message which drug education agencies have been preaching for years.

The threat of drug use amongst young people in the countryside, evident to those working in the area for some time, is emphasised in a new report produced by the school health education unit of Exeter University, headed by John Balding. This shows that 27 per cent of 14-15 year olds living in rural areas have experimented with at least one drug, whereas the figures are 21 per cent for young people from the suburbs, and 18 per cent for those in an urban environment. The research was carried out among 23, 317 children in 122 schools. There is some good news in this same report. It indicates that young teenage drug use is falling for the first time in five years. 25 per cent of 14-15 year olds tried drugs last year as compared to 33 per cent in 1996. However, despite this drop, the long-term trend is upwards. “The percentage of youngsters of 12 to 13 in 1996 that recorded experience of illegal drugs was greater than that of 15 to 16-year-olds in 1987.”

Hardened drug users are also on Keith Hellawell’s agenda. These are believed to be responsible for £1 billion of property crime every year in the United Kingdom. At an expected cost of £7 million, the plan is to provide every gaol in England and Wales with a drug free wing. These already exist in a number of prisons where organisations like RAPT have units for the rehabilitation of addicted prisoners. Inmates will have to undergo regular testing in return for concessions. At the moment, according to unpublished Prison Service figures, 20 per cent of tested prisoners show traces of drugs despite the effort being put into preventing the smuggling of illicit substances. George Howarth, the Home Office minister responsible for prisons, said, ” We plan to have a voluntary testing unit in every prison. That is the key to a drug-free environment.”

The new strategy shortly to be unveiled by Mr Hellawell’s team will call for £40 million funding for drug treatment and testing schemes. These will force those convicted of crimes related to the financing of a drug habit to undergo rehabilitation treatment and tests. Those who fail would face imprisonment. Pilot schemes in South London, Merseyside, and Gloucestershire begin this summer.