In this month’s alert

No alcohol for under fifteens

An alcohol-free childhood is the healthiest option, and if children do drink alcohol, it should not be before they reach the age of 15 years, according to new governmental advice to parents issued by the Chief Medical Officer.

The advice forms a main part of the Youth Alcohol Action Plan, published in June 2008 by the Department for Children, Schools and Families. It is in the form of a consultation document, with parents, health professionals, young people themselves and all other interested parties being invited to comment on the Chief Medical Officer’s assessment of the issue of drinking by children and adolescents and his proposals for reducing the harm associated with it. A particular feature of the new advice is guidance in regard to what counts as low risk drinking for children and adolescents, the generally known guidelines on low risk or `sensible’ drinking being based on evidence pertaining to adult populations. In relation to this, Sir Liam states that alcohol consumption during any stage of childhood can have a detrimental effect on development and, particularly during teenage years, is related to a wide range of health and social problems. Vulnerability to alcohol-related problems, Sir Liam says, is greatest among young people who begin drinking before the age of 15. The safest option, therefore, is for children not to drink at all until they are at least 15 and, preferably, 18. Sir Liam Donaldson formulated the advice on the basis of extensive research and work with a panel of experts who reviewed the latest available medical evidence and data from across the UK on the impact of alcohol and young people. Dr Rachel Seabrook, Research Manager of the IAS, was a member of the expert panel.

Launching the advice, Sir Liam Donaldson said: “This guidance aims to support parents, give them the confidence to set boundaries and to help them engage with young people about drinking and risks associated with it.

“More than 10,000 children end up in hospital every year due to drinking and research tells us that 15 per cent of young people think it is normal to get drunk at least once a week. They are putting themselves at risk of harm to the liver, depression and damage to the developing brain. Resulting social issues can lead to children and young people doing less well at school and struggling to interact with friends and family.”

Ed Balls, Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families, said: “Parents have told us that they lack the health information and advice they need to make decisions about whether or how their children should be introduced to alcohol. So I hope the Chief Medical Officer’s advice will help them with the tricky task of deciding the best way of doing that.

“We want this advice and information to be a success and really help families. That’s why we’re asking young people, parents and all those interested for their views. I think all of us as parents need to look at this advice, see whether it’s right for us and ask whether we are doing the best thing for our children.

“Alcohol is a part of our national culture and if managed responsibly can have a positive influence in social circumstances. However when it is not managed responsibly it can cause real problems.”

Speaking for IAS, Rachel Seabrook said: “The Institute of Alcohol Studies welcomes these new guidelines recommending that children should not start to drink alcohol before the age of 15 and emphasising the importance of parental influence on young people’s drinking. We know of no evidence supporting the idea that introducing alcohol to children or young teenagers can protect them against dangerous drinking habits, whereas there is a considerable body of research showing a link between starting to drink at a young age and problems with alcohol in later life.

Additionally, young people need to be aware of the risks of drunkenness. Some of the dangers are far worse than vomiting and waking up on a friend’s sofa.”

The Guidance

The new advice specifically addresses the key points requested by Government in the Youth Alcohol Action Plan, and it is given in terms of 5 key points:

- Children and their parents and carers are advised that an alcohol-free childhood is a healthy option. However, if children drink alcohol, it should not be before they reach the age of 15 years.

- For those aged 15 to 17 years all alcohol consumption should be with the guidance of a parent or carer or in a supervised environment.

- Children aged 15 to 17 years should never exceed adult recommended daily maximums. As a general guide, children aged 15 and 16 years should not usually drink on more than one day a week. Children aged 17 should drink on no more than two days a week.

- Parental influences on children’s alcohol use should be communicated to parents, carers and professionals. Parents and carers require advice on how to respond to alcohol use and misuse by children.

- Support services must be available for children and young people who have alcohol-related problems and their parents.

The CMO’s advice and the consultation document are accompanied by new reviews of the evidence in regard to alcohol consumption by children and adolescents which provide the scientific basis of the new advice. In regard to the advice that young people should delay the age they start drinking alcohol, this is because the evidence suggests that:

- children who begin drinking at a young age drink more frequently and in greater quantities than those who delay drinking. They are also more likely to drink to get drunk

- the earlier they start drinking alcohol, the more they are at risk of alcoholrelated injuries, involvement in violent behaviour and suicide attempts, having more sexual partners and a greater risk of pregnancy, using illegal drugs and experiencing employment problems and driving accidents

- heavy drinking during adolescence may affect normal brain functioning during adulthood. Furthermore, young people who drink heavily may also develop problems with liver, bone, growth and endocrine development; and

- the earlier they start drinking alcohol the more likely they are to develop alcohol abuse problems or dependence in adolescence and adulthood.

In regard to levels of consumption, the Chief Medical Officer recommends that :

“Children aged 15 to 17 years should never exceed adult recommended daily maximums (of 2-3 units for women and 3-4 units for men on any single day). As a general guide children aged 15 and 16 years should not usually drink on more than one day a week. Children aged 17 should drink on no more than two days a week.”

The CMO explains that children and young people who drink frequently and binge drink are more likely to suffer alcohol-related consequences. While individuals vary in the way that they react to the consumption of alcohol, young people may have a greater vulnerability to certain harmful effects of alcohol use than adults. Young people also lack drinking experience and decision-making skills about amount, strength and speed of drinking. Brain development continues throughout adolescence and into young adulthood, and drunkenness, binge drinking or exceeding recommended maximum alcohol limits for adults should always be avoided.

The CMO advice is that frequent or excessive drinking by children and young people is particularly dangerous because:

- it presents particular risks in terms of health, unplanned and unprotected sexual activity and violent behaviour

- it is more likely to lead to binge drinking and alcohol dependence in young adulthood

- it leads to a higher likelihood of involvement in illegal drug use, crime, and lower educational attainment

The importance of parents

In regard to the role of parents, the CMO recognises that they face a difficult task, and that many may feel ill-equipped to deal with their children’s current or future drinking. His advice to them is to:

- set limits and determine the consequences for drinking behaviour

- negotiate boundaries and rules for appropriate behaviour in relation to alcohol; and

- show disapproval of alcohol misuse, such as getting drunk, drinking when they have been told not to or getting into trouble after drinking

This advice is based on the evidence that:

- a permissive approach by parents to the use of alcohol by their children often leads to heavy and binge drinking in adolescence

- family standards and rules, as well as parental monitoring, delay the age at which young people first drink

- frequent or excessive drinking by parents increases the likelihood that children will also consume more alcohol and be at greater risk of harm; and

- warm and supportive parent–adolescent relationships lead to lower levels of adolescent alcohol use and misuse.

Further details can befound at: www.dcsf.gov.uk/consultations

The closing date for the consultation is 23 April 2009.

Do the new licensing laws make things worse for young adults?

In a new “for debate” piece published in the scientific journal Addiction, researchers question whether current licensing policies have contributed to a rise in the phenomenon of “pre-drinking” amongst young people.

“Pre-drinking” or “pre-gaming” involves planned heavy drinking, usually at someone’s home, before going to a social event, typically a bar or nightclub. As defined by young people themselves, pre-drinking is “[the] act of drinking alcohol before you go out to the club to maximise your fun at the club while spending the least amount on extremely overpriced alcoholic beverages”.

Culture of Intoxication

Drawing on scientific evidence from various countries as well as information from media and popular internet vehicles, the authors suggest that pre-drinking is symptomatic of a “new culture of intoxication” whereby young people are drinking with the primary motive of getting drunk. Recent research suggests that a large proportion of young people pre-drink and that pre-drinkers are more likely to drink heavily and to experience negative consequences as compared to non-pre-drinkers. Pre-drinking often involves the rapid consumption of large quantities of alcohol which may increase the risk of blackouts, hangovers and even alcohol poisoning. It may also encourage the use of other recreational drugs such as cannabis and cocaine as drinkers are socialising in unsupervised environments.

The authors argue that the policy of banning drink promotions or specials such as “happy hour” in bars and clubs may have the unintended consequence of encouraging young people to drink cheaper alcohol in private settings before going out, especially when alcohol is offered at much lower prices in off-premise outlets. The authors also point out that while later closing times have been justified as a way of reducing problems associated with large numbers of young people being on the street after bars and clubs close, they may encourage private drinking to precede rather than follow public drinking, producing different social dynamics and possibly increasing the potential for violence and other alcohol-related problems.

To discourage or reduce pre-drinking, the authors suggest a comprehensive strategy including:

- Developing policies that reduce large imbalances between on and off premise alcohol pricing

- Attracting young people of legal drinking age back to the bar for early drinking, where alcohol consumption is monitored by serving staff and drinks are served in standard sizes

- Addressing young people’s motivations for pre-drinking, including being able to socialize with friends and saving money – for example, bars might expand their social function and create an attractive atmosphere for more intimate socializing

- Forming effective strategies to reduce planned intoxication – for example, policy and programming could be aimed at changing drinking norms and promoting moderation.

Lead author, Dr. Samantha Wells, a researcher at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) in Canada says, “Many young bar-goers have found a way to avoid paying high alcohol prices in bars: they pre-drink. And we have begun to see that this intense and ritualized activity among young adults may result in harmful consequences. Therefore, we need to look closely at the combined impact of various policies affecting bars and young people’s drinking and come up with a more comprehensive strategy that will reduce these harmful styles of drinking among young people.”

Wells S., Graham K., Purcell J. Policy implications of the widespread practice of “pre-drinking” or “pre-gaming” before going to public drinking establishments – are current prevention strategies backfiring? Addiction 2009; 104: 4-9

No reason to be sanguine about teenage drug use

Kathy Gyngell – Research Fellow at the Centre for Policy Studies – comments on the National Treatment Agency’s report ‘Getting to grips with substance misuse among young people: the data for 2007/08’

Last week the NTA published the staggering figure of nearly 25,000 young people under 18 getting treatment for their drugs and alcohol problems.(1) Up some 8,000 on just a year and a half ago, this, they insist, is not a reflection of a growing problem but just one of expanding services.

This does not, however, leave me feeling much happier. Ten years ago the thought of so many young teenagers using drugs to this degree was unimaginable. Yet the evidence of the continuing catastrophic levels of school age drug use suggests that should ‘services’ go on to double or treble, demand will take that up too.

The sad fact is that, despite ten years of a drug strategy purportedly designed to reduce use by young people, there are thousands of children beginning their lives so damaged by drugs that they need treatment.

Whatever the spin put on these figures, this is a major social problem that can neither be denied nor brushed under the carpet. What teenagers do today determines the scale of the drugs problem tomorrow.

But, as ever in the rose tinted world of British drugs policy, we are told by the great and the good that there is nothing much for us to worry about.

Drugscope’s sanguine response to the figures was that, “Public and media perceptions of the numbers of young people misusing drugs and alcohol can be distorted. Yet the picture painted by prevalence data ……. all suggest that the numbers of young people using drugs and alcohol are falling”.(2)

However, the national school age statistics on drugs use, which Drugscope portrays as revealing this good news, still show that a staggering 25% of the UK’s school age children (11 – 15) have tried drugs – fi gures that are way higher than the European average – and that 10% of them are using drugs regularly.(3) The last comparable survey fi gures for European school children under 15 also showed UK to have 13% of our under 13s having tried cannabis against a European average of 4%.(4) It is also the case that, while the trend for schoolchildren’s drug use remained stable across Europe between 1999 and 2005, in the UK it doubled. Although UK school childrens’ drug of choice, cannabis, appears to have now stabilised, their cocaine consumption has been rising – unheard of elsewhere in Europe.

But it is also likely that levels of teenage cannabis use are higher than the published statistics state, as the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs recently acknowledged. In their view the British Crime Survey is likely for a range of reasons to underestimate it. Even so, these estimates show that some 12% of 16 -19 year olds are regular users and that 20% of them have used it in the last year.(5)

A percentage point decline in cannabis use in official statistics is small comfort for parents or for schools. Hospital admissions show that this small gain has been wiped out by the rising strength of cannabis and by the fact that children are moving earlier to Class A drugs. In fact with the UK cannabis market dominated by high THC skunk, which, according to a former head of the Dutch Police Narcotics Division, should now count as a ‘hard drug’, what we are witnessing is an ever earlier and disturbing shift to hard drug use. To dismiss such concerns as distorted perceptions is really not on. As any ‘in touch’ parent of a teenager in central London knows, regular cannabis using kids are moving to cocaine, ketamine and ecstasy by the time they are 16 or 17. Many teenagers appear to be immune to drug dangers despite the endless compulsory personal health and social education classes that they are subjected to at school. Nor has the government’s mixed message about drugs helped – namely their explicit policy statements about the non harmful nature of ‘recreational’ and casual drug use; no more helpful is their confused ‘informed choice’ approach to drugs education.

The appalling truth, as far as adults are concerned, is that we seem to have surrendered to a sense of ‘inevitability’ about children’s drug use.

While drugs services and drugs advisors have no more urgent need than to highlight “the problems faced by young people when they reach 18 and are no longer eligible for specialist services” and “to ease their transition to adult services”, the outlook is dire indeed.

The NTA’s tables reveal that 1600 teenagers are receiving treatment for heroin, cocaine and crack addiction and that 29% – some 6000 in all of those in treatment – are now receiving ‘harm reduction’ interventions – usually understood to be a euphemism for prescribing an opiate substitute like subutex or methadone. As Professor Neil McKeganey, a leading expert in drugs misuse has said: ‘The idea of starting someone under 18 on a methadone prescription with an implicit expectation that they may be on that drug for the next ten or more years is appalling. We need services to think beyond the chemical inducement into therapy.’(6)

The desperate fact though, is that there is still only one small dedicated residential rehabilitation centre with statutory funding for no more than 12 children/ teenagers at a time in the country. Last year Mike Trace, Chief Executive of RAPT – the Rehabilitation of Addicted Prisoners Trust – spoke of the urgent need for residential treatment for young, under 18, addicts.(7) Young addicts, he said, were unlikely to get better within the environment in which they had grown up and that had fed their problems. Any parent of a young addict knows just how truly he spoke.

But how much of the National Treatment Agency’s dedicated funding of £25 million is being spent on this? How many teenagers are emerging drug free from their encounters with services? How effective are the disparate psychosocial interventions, pharmacological prescribing interventions, specialist harm reduction, and family interventions on offer? It is simply not enough for the NTA to tell us that the proportion of young intervention according to the goals set out in their care plans’ is 57%. Unless we know what the goals of their care plans are in the first place and what the aspirations are for the young people in question, it is a pretty meaningless statement. As we already know from adult services ‘completing treatment’ may be a measure of virtually nothing.

References

(1) Getting to Grips with substance misuse amongst young people: data for 2007/8. NTA January 22nd 2008

(2) Drugscope Press Release 22nd January 2008

(3) Drug Use, Smoking and drinking among young people in England 2007, NHS, The Information Centre

(4) EMCDDA Drug use and related problems among very young people (under 15 years old), 2007

(5) Cannabis classification and public health, ACMD 2008

(6) Addictions, Vol 4, Breakthrough Britain

(7) BBC News 20.09.08

NHS needs new approach to tackle nation’s unhealthy lifestyles – The King’s Fund

The NHS will fail to tackle the rising tide of obesity and tobacco related illnesses unless it adopts more sophisticated techniques including those employed by commercial advertisers to help people to live healthier lifestyles.

That is one of the conclusions of a yearlong investigation into the effectiveness of different types of public health programmes to tackle smoking, alcohol misuse, poor diet and lack of exercise published by The King’s Fund, the independent think tank specializing in health issues.

The report finds that these behaviours are deep rooted social habits that are not easily changed by one-off, short-lived measures. The report also adds that many NHS staff lack the necessary skills and incentives to help people effectively to choose and maintain healthier lifestyles.

The King’s Fund Director of Policy and report co-author, Dr Anna Dixon, said:

‘The health service needs to be more innovative in how it tackles unhealthy behaviour. Obesity and the health problems associated with smoking and excessive alcohol are the biggest challenges facing the 21st-century NHS.

‘The methods used topromote public health need to be more modern, using the most advanced techniques and technologies.

‘The reasons people persist with unhealthy habits are complex. It’s often about changing deep-rooted social habits that can become addictive, rather than just helping people make better choices as individuals.

‘Financial incentives and information campaigns can be useful but are far more likely to lead to real and long-term changes in people’s behaviour when paired with other interventions like tailored information and personalised support.

‘But at the moment there simply isn’t enough reliable data on what works and what doesn’t, to help health service managers plan appropriate behaviour change programmes to meet their local needs. This lack of evidence has to be urgently addressed so more money isn’t wasted on ineffective interventions.’

- Commissioning and behaviour change: Kicking Bad Habits final report makes a series of recommendations:The NHS needs to make better use of social marketing techniques and data analysis tools like geodemographics to identify, target and effectively communicate messages and motivate people to change how they live.

- Public health programmes should not rely on just one approach – such as information campaigns or financial incentives – as the evidence shows the most effective behaviour change interventions employ a variety of tactics.

- A robust evaluation – of short- and long-term changes in behaviour and health outcomes – should be made a requirement of all public health programmes in order to build an evidence base for the future. Frontline staff should be more proactive in promoting healthy habits to the patients they see every day and for contracts and incentives to be used to encourage such behaviour.

- Government departments and local agencies involved in tackling unhealthy behaviours must better co-ordinate their efforts and ensure that targets are agreed to support their shared objectives.

Dr Dixon added:

‘Encouraging healthier lifestyles is the job of all staff working within the health service, not just those working specifically in public health. GPs, pharmacists and hospital staff, the people that interact with patients every day, need to be trained in behaviour change techniques to give them the confidence to start conversations about people’s unhealthy habits and to be effective in influencing their lifestyles.

‘For the NHS to truly change from a service treating illness to one promoting good health, all government bodies and local health agencies need to work together. The responsibility to promote good health, as well as treat sickness, needs to be fully embedded in national policies, Primary Care Trusts’ priorities, care providers’ standards and performance indicators, and staff and service contracts.”

New Alcohol Profiles show alcohol related disease is still increasing – North west a blackspot

The latest Local Alcohol Profiles for England (LAPE) show there were around 800,000 alcohol-related admissions to hospital in England in 2006/07, a 9% increase from the previous year or an additional 174 alcohol-related admissions every day. The 800,000 admissions were accounted for by 530,000 individuals, as some people had more than one stay in hospital during the year.

The figures were compiled by the North West Public Health Observatory at the Centre for Public Health. The profiles contain 23 measures of the burden that alcohol has on local communities. They include the Government’s national indicator – hospital admissions for alcohol related harm (NI 39) – as well as other measures such as alcohol-related deaths, crime and incapacity benefit claimants.

Dr Karen Tocque, Director of Science and Strategy for the North West Public Health Observatory and lead for the development of the alcohol profiles, said “For the first time, local communities can see the effect that alcohol has been having over a four or five year period and these trends may come as a bit of a surprise. No area of England can escape the fact that alcohol is having some negative influence on their residents. Each year, people living in each community become a victim of a crime, are unable to work, are admitted to hospital or may even die – all because of alcohol.”

Professor Mark Bellis, Director of the North West Public Health Observatory added:

“Rises in alcohol-related health problems reflect not only weekend binge drinking but also how use of alcohol on a nightly basis continues to erode our health. Further increases in alcohol problems are in store if we continue to focus on the symptoms of alcohol misuse, like night life violence and ill health, but ignore the causes such as cheap alcohol and a lack of recognition that alcohol is a dangerous drug.”

The alcohol profiles can be accessed on the web at www.nwph.net/alcohol/lape

Key findings from the profiles:

-

- New figures for the National Alcohol Indicator (NI 39) – hospital admissions for alcohol related harm

- Numbers of people being admitted to hospital each year continue to climb – up 7% or 34,000 more people admitted since 2005/06

- On a national basis, deaths from chronic liver disease increased in the last year by 7% for women and 5% for men

- Claims for Incapacity Benefit and Severe Disablement Allowance due to alcoholism remain static at around 41,000 (for November 2007) whilst transport accident deaths attributable to alcohol have decreased by 10% since 2003 to 2,900 in 2007

- While there are variations in trends between Local Authority areas, 63% showed an increase in hospital admissions in the last year, 31% had less than 5% change and only 6% showed a decrease

- In general, those areas of the country high for one measure of alcohol problem are high for others and therefore, a single measure of harm was created to compare areas. This measure includes alcohol-related ill health, death, crime and poor drinking behaviours. With the exception of Middlesbrough, Hammersmith and Fulham, and Kingston upon Hull, seven of the ten areas in England with the greatest level of alcohol related harms are in the North West region: Manchester, Salford, Liverpool, Rochdale, Halton, Tameside and Oldham

- The local areas least affected by alcohol are mostly in the South East or Eastern regions of the country: Wokingham, Mid Bedfordshire, Three Rivers, Castle Point, North Kesteven, South Northamptonshire, Sevenoaks, East Dorset, Broadland and South Norfolk

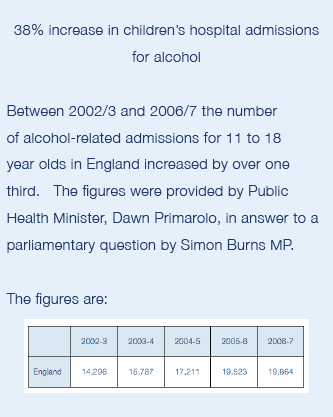

- Children and young people (under 18 years of age) being admitted to hospital because of alcohol have risen nationally by around 5% a year since 2003/04 to nearly 8,000 in 2006/07. However, the areas with the highest rates are not the same places where adult admissions are highest but, instead, are often more rural and isolated areas and include: Copeland, Isle of Wight, Darlington, Redditch, Rossendale, Wirral, Halton, Sunderland, Kingston upon Hull and Wear Valley.

Reducing alcohol harm – Health services in England for alcohol misuse

Alcohol related ill-health is an increasing burden for the National Health Service, and alcohol harm costs the health service in the order of £2.7 billion a year, but efforts to address it locally are not in general well planned, according to the National Audit Office (NAO).

In a report published in October 2008, the NAO examined the NHS response to the rising levels of alcohol-related disease. Hospital admissions for the three main alcohol specific conditions (alcohol-related liver disease, mental health disorders linked to alcohol, and acute intoxication) have doubled in the last 11 years. There were also twice as many deaths from alcohol related causes in the UK in 2006 as there were 15 years before, increasing from 4,100 to 8,800.

The Department of Health is raising the profile of alcohol misuse by providing information and guidance to underpin local action, centred on encouraging Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) to gauge their performance against the rate of alcohol related hospital admissions. However, the NAO found their response to be patchy.

Primary Care Trusts are responsible for setting local health priorities. But around a quarter of PCTs surveyed by the NAO had not fully assessed alcohol problems in their areas. Many PCTs do not have a clear picture of their spending on services to address alcohol misuse and its effects on health. PCTs have often looked to their local Drug and Alcohol Action Teams to take the lead, but these bodies focus primarily on specialist services for dependent users of illegal drugs and alcohol. The NOA concluded that there is scope for the Department of Health to provide greater leadership to PCTs on alcohol misuse, and the NAO report recommends a number of specific measures to that end, such as guidance to help PCTs assess causes and to forecast trends in the level of alcohol harm in their localities.

There is evidence that ‘brief advice’ by GPs and health workers, can reduce alcohol consumption and help to prevent longer term damage to health and there are some good local examples of this. From September 2008 the Department has provided an additional £8 million in support for such services. For people who have developed severe alcohol problems, there are considerable variations between different localities in access to specialist treatment services, and scope for better integration of hospital treatment with follow on services such as psychiatry.

The Department has recently undertaken a series of new publicity campaigns to encourage `sensible drinking’. Research has shown that consumers tend to underestimate the amount of alcohol their drinks contain and are not clear about what is meant by a ‘unit’ of alcohol. Department of Health funding for such work was tripled to £6 million in 2008/09.

Tim Burr, head of the National Audit Office, said:

“Alcohol misuse constitutes a heavy and increasing burden on the NHS. If services to tackle alcohol misuse are going to make a bigger difference, Primary Care Trusts need to understand better the scale of the problem in their local communities. With its increased focus on the prevention of lifestyle-related illness, the Department of Health could, for example, do more to convince Trusts about the value of timely advice to help people develop safer drinking patterns.”

The National Audit Office report ‘Reducing alcohol harm: health services in England for alcohol misuse can be downloaded at: http://www.nao.org.uk/publications/0708/reducing_alcohol_ harm.aspx

Government calls time on irresponsible drink deals

A ban on ‘all you can drink’ promotions in pubs and bars was among a range of new measures announced by Home Secretary Jacqui Smith and Health Secretary Alan Johnson, supported by a new £4.5 million crackdown on alcohol fuelled crime and disorder. The measures will form part of the legislative programme announced in the Queen’s Speech in November 2007.

Following an independent review, which found that many retailers were not abiding by their own voluntary standards for responsible selling and marketing of alcohol, the Government now intends to introduce a new mandatory code of practice to target “the most irresponsible” retail practices. The code will set out compulsory licensing conditions for all alcohol retailers, and will give licensing authorities new powers to clamp down on specific problems in their areas. Licensing authorities will also be able to impose these new powers on several premises at once. The mandatory code will be enforced through the current licensing regime and will apply to all premises licensed to sell alcohol – including private members clubs. Any breaches of these conditions will lead to a review of the licence (and possible loss of licence) or, on summary conviction, a maximum £20,000 fine and/ or six months imprisonment.

The Government announced that it would consult interested parties on a range of compulsory conditions including:

- banning offers like ‘all you can drink for £10’

- outlawing pubs and bars offering promotions to certain groups, such as women only

- ensuring that customers in supermarkets are not required to buy very large amounts of a product to take advantage of price discounts

- ensuring staff selling alcohol are properly trained

- requiring that consumers are able to see unit content of all alcohol when they buy it; and

- requiring bars and pubs to have the minimum sized glasses available for customers who want them.

The Government also announced that Crime and Disorder Reduction Partnerships are being awarded a £3 million cash injection to target enforcement activities on specific alcohol-related problems in 190 areas across all police forces. In addition, £1.5 million will be given to a number of priority areas to strengthen their ability to tackle underage sales, confiscate alcohol from under 18s and run communications campaigns to tell people what action is being taken to reduce alcohol-related crime and disorder successfully in their local area.

Home Secretary Jacqui Smith said:

“I don’t want to stop the vast majority of people who enjoy alcohol and drink responsibly from doing so but we all face a cost from alcohol related disorder and I have a duty to crack down on irresponsible promotions that can fuel excessive drinking and lead people into crime and disorder. That’s why I will impose new standards on the alcohol industry that everyone will have to meet with tough penalties if they break the rules.

“There is no simple solution to tackling this problem – we all have a responsibility to tackle the binge drinking culture. I look forward to seeing the results of our £4.5 million crackdown on alcohol fuelled crime and disorder.”

The Government undertook a public consultation on a mandatory code in July this year. Over 90 per cent of approximately 2,000 respondents supported a mandatory code.

Mike Craik, Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) lead for Alcohol Licensing, welcomed the measures. He said:

“For too long, some retailers have been putting profits before responsibility and cutting the price of alcohol until it is cheaper than water.

“There is no doubt that irresponsible drinking leads to alcohol-fuelled violence and suggestions that enforcement alone can provide an answer ignore the obvious. Last year, nearly one fifth of all violent incidents took place in or around pubs and clubs at a cost of £7.3 billion to the UK. While there are many who trade responsibly, there are also, as the KPMG study released earlier this year showed, a great many who do not. So the industry has an important part to play in helping to reduce the excessive drinking that leads to alcohol-fuelled disorder on our streets. “ACPO has consistently called for end-to-end solutions bringing together the police, local authorities, industry, parents and all those in each neighbourhood who share an interest in tackling alcohol-related crime and disorder. We look forward to working with Government and partners on proposals to meet this aim.”

David Poley, chief executive of the Portman Group, the social responsibility organisation for drinks producers, also welcomed the proposed mandatory code as a method of strengthening the existing licensing laws while allowing effective producer selfregulation to flourish. The code would “stamp out irresponsible promotions without making everyone pay more for a drink”.

Alcohol pricing and promotion

To assist policy making, and as foreshadowed in the National Alcohol Harm Reduction Strategy, the Government tendered for a research report on the effects of alcohol pricing and promotion. In the event, the contract was awarded to a research team at Sheffield University, and the report was published in two parts.

The first part provided a systematic review of the international evidence on the link between the price and promotion of alcohol on the one hand and patterns of consumption and alcohol related harm on the other, as well as the effectiveness of related policy interventions. In particular, the review indicated how the promotion and pricing of alcohol affects total alcohol intake, and patterns of consumption in groups identified as priorities by government, namely underage drinkers, young adult binge drinkers, heavy drinkers, and those on low incomes. The second part modeled the potential implications of changes to current policies on alcohol taxation and promotion, especially the impact on health, crime, and employment.

The researchers found that the exact size of the impact of price measures varied between countries and a major limitation of the evidence base is that most studies examining the impact of such policies have been conducted in the United States. Nevertheless, they say there is very strong evidence for the effectiveness of alcohol taxes in targeting young people, heavy drinkers and the harmful effects of alcohol.

Dr Petra Meier “This is the first study to integrate data on alcohol pricing and purchasing patterns, consumption and harm, to answer the question of what would happen if government were to introduce different alcohol pricing policies. The results suggest that policies which increase the price of alcohol can bring significant health and social benefits and lead to considerable financial savings in the NHS, criminal justice system and in the workplace. “

The second part of the University of Sheffield report amplifies the finding that alcohol pricing policies are effective in reducing alcohol related health, crime and social costs, and it analyses over 40 separate policy scenarios, including setting minimum prices per unit of alcohol at different levels and bans on price-based promotions in off licenses and supermarkets.

The results of the research show that targeting price increases at cheaper types of alcohol would affect harmful and hazardous drinkers far more than moderate drinkers. Heavier drinkers, by defnition, buy more alcohol, but detailed analysis of data on purchasing patterns also shows that they tend to buy more of the cheaper beers, wines and spirits. The effects of price increases may incidentally be advantageous for alcohol retailers (both in off-trade and on-trade) because the estimated decrease in sales volume is more than offset by the unit price increase, leading to overall increases in revenue.

The detailed findings of the research are:

Across the board price increases can have a substantial impact on reducing consumption, and consequently, harm. Such price increases mean that there is less incentive for switching between different types of alcohol or drinking venues (for example by going to the pub if supermarket alcohol is getting more expensive) than in policies targeting price increases at certain products or market sectors. Pubs and supermarkets are equally affected by a general price increase, although it has been argued that supermarkets may be less likely than pubs to pass on such price rises to consumers.

Across-the-board price increases (covering all products in the on-trade and off-trade) tend to lead to relatively larger reductions in mean consumption for the population, compared to other pricing options.

Policies targeting price changes specifically on low-priced products or certain product categories lead to smaller changes in consumption, as they only cover a part of the market.

Minimum pricing is a policy which sets a minimum price at which a unit of alcohol can be sold. Price increases are targeted at alcohol that is sold cheaply. Cheaper alcohol tends to be bought more by harmful drinkers than moderate drinkers and studies show that it is also attractive to young people. So a minimum price policy might be seen as beneficial in that it targets the drinkers causing the most harm to both themselves and society whilst having little effect on the spending of adult moderate drinkers.

Approximately 27% of off-trade alcohol consumption is purchased for less than 30p per unit, compared to 9% in the on-trade. 59% of off-trade consumption and 14% of on-trade consumption is purchased for less than 40p per unit.

Increasing levels of minimum pricing show very steep increases in effectiveness. Overall reductions in consumption for 20p, 30p, 40p, 50p, 60p, 70p are: 0.1%, 0.6%, 2.6%, 6.9%, 12.8% and 18.6%. Minimum prices targeted at particular beverages are less effective than all-product minimum prices. Differential minimum pricing for on-trade and off-trade leads to more substantial reductions in consumption and harm (for example, pairing a 30p minimum price in the off-trade with an 80p on-trade minimum price gives a reduction in consumption of 2.1% compared to 0.6% for off-trade alone.

In relation to off-trade promotions and discounts (such as buy one get one free offers), just over 50% of all alcohol purchased from supermarkets is sold on promotion, although many of the discounts are quite small. Only quite tight restrictions on the level of discount offered would have noticeable policy impacts. For example, banning only buy-one get-one free offers has very little effect on consumption and harm. Bans on discounts only for lower-priced alcohol (less than 30p per unit) are also not effective in reducing consumption. A ban on discounts of greater than 20% (which would prohibit buy-one-get-one-free, buy two- get-one-free and buy three- get-one-free) leads to overall harm reductions similar to a 30p minimum price.

A total ban on off-trade discounting is estimated to reduce consumption by 2.8%, although this may only prove effective if retailers were also prevented from responding by simply lowering their non-promotional prices.

In regard to alcohol advertising, it is unclear whether advertising restrictions can be expected to have an immediate effect on consumption. The international evidence suggests that effects of advertising may be cumulative over time, and may work through influencing attitudes and drinking intentions rather than consumption directly. In regard to the savings for each policy the review has looked at relating to health harm, the general pattern is that the more restrictive the policy, the greater the harm reduction.

Higher minimum prices lead to greater harm reductions, and this goes up steeply – for example, there is relatively little effect for a 20p minimum price, but 30p, 40p, 50p and 60p have increasing effects. Similarly, a ban on just BOGOFs (buy-one-get-one-free) does not affect health harm very much, but banning discounts larger than 10%, or even a total ban on sales promotions in the off-trade lead to substantial estimated harm reductions.

For example: A 40p minimum price gives an estimated reduction of around 41,000 hospital admissions per annum.

A minimum price of 30p is estimated to reduce total crimes by around 3,800 per annum whereas a 40p minimum price is estimated to reduce crimes by 16,000 per annum and a 30p offtrade paired with an 80p on-trade minimum price by 68,000 per annum. An off-trade discount ban would lead to an estimated prevention of 14,000 crimes per annum, of which 4,000 are violent offences.

Crime harms are estimated to reduce particularly for 11-18 year-olds as they are disproportionately involved in alcohol-related crime and are affected significantly by targeting price rises at low-priced products. Crime costs are also estimated to reduce as prices increase. A 30p, 40p and 30p(off-trade)/80p (on-trade) minimum price is estimated to lead to direct cost savings of around £4m, £17m and £65m per annum respectively, whereas the value of gains in quality of life associated with decreased crime is estimated at £4m, £21m and £88m per annum respectively.

A ban on price promotions in the off-trade decreases direct crime costs by £18m per annum and the cost of quality of life lost by £25m per annum. It is important to note that different policies emerge as effective when compared to health harms: discount bans, targeting cheap off-trade alcohol and low minimum pricing options, which influence only the off-trade sector, are all less effective in reducing crime when compared to policies that also affect the on-trade sector. This is because many of the offenders are young males who purchase just over 75% of their alcohol in the on-trade.

The main conclusion of the study, overall, was that pricing policies can be effective in reducing health, crime and employment harm. Pricing policies can be targeted, so that those who drink within recommended limits are hardly affected and so that very heavy drinkers, who cause by far the most alcohol-related harm, pay the most. Minimum unit pricing and bans on alcohol discounting could save hundreds of millions of pounds every year in NHS, crime and employment costs. If policy makers wish to see the greatest impact in terms of crime and accident prevention, through reducing the consumption of 18-24 year old binge drinkers, they need to consider policies that increase the prices of cheaper drinks available in pubs and clubs as well as supermarkets.

The Independent Review report can be downloaded at: http://www.dh.gov. uk/en/Publichealth/ Healthimprovement/ Alcoholmisuse/DH_4001740

Community pharmacies promote alcohol awareness

Community pharmacies are being mobilized to promote alcohol awareness as part of the `Know Your Limits’ campaign. Dr Keith Ridge, the Chief Pharmaceutical Officer, has written to pharmacists urging them to participate and a special campaign pack has been distributed to help them.

Community pharmacies and staff are regarded as key to ensuring that the national campaign messages are communicated to the general public. In England, most people’s first – and sometimes only – contact with a pharmacist is through their local community pharmacy. Approximately 1.6m people walk into pharmacies everyday and 1.2m walk in for health-related reasons. In the past six months three-quarters of people have visited a community pharmacy.

Community pharmacists are, therefore, particularly well placed to deliver health messages to the public. The activity pack is designed to support pharmacists and their staff in promoting awareness of the alcohol units messages. The pack gives ideas and guidance on how the awkward subject of alcohol can be approached with customers and on how pharmacies can work with the local media and health professionals to promote the message.

Alcohol pledge Wales campaign

The most senior churchmen and police officers in Wales have joined forces in a campaign to tackle the culture of binge drinking by spreading the message that “Enough is Enough”. The centerpiece of the campaign is a pledge that drinkers are invited to sign in which they commit themselves not to `binge’ drink.

The Archbishop of Wales with the six other Welsh Bishops and the four Chief Constables of Wales lead the campaign which is supported by a wide range of other organizations. It is aimed to tackle the range of problems associated with excessive drinking, from out-of-control revellers in city centres on a Saturday night to people regularly consuming too many bottles of wine at home on weekday evenings.

As part of the campaign, people concerned about how much they drink are invited to take a “Pledge” to cut down the amount they drink and to stop before they have had too much. Drinkers can sign up to the Pledge online and carry a card to remind them of their commitment and give them support against peer pressure.

Posters and leaflets are being circulated to remind people of the damaging effects of binge drinking and the huge cost it has on themselves, their families and friends and society as a whole.

The campaign supports the Welsh Assembly Government’s Substance Misuse Strategy.

Launching the campaign, the Archbishop of Wales Wales, Dr Barry Morgan emphasised that the challenge of today’s Pledge was not to give up alcohol altogether but to give up binge drinking:

“Alcohol isn’t the problem – it is our attitude to it that counts. Drinking can be an enjoyable part of our social life but not when we abuse it – harming ourselves and others. The challenge is to change our own thinking and the prevailing culture and attitude in Wales which equates a good night out, or even a good night in, with drinking to excess.

“This is what needs challenging and this is why we are saying Enough is Enough.”

Those interested can signup for the pledge at: www.alcoholpledge.co.uk

New publication – Raising the bar – preventing aggression in and around bars, pubs and clubs

By Kathryn Graham & Ross Homel

Reviewed by Audrey Lewis, Chair of Licensing Committee, Westminster City Council

How many readers of this publication are responsible for managing large pubs, bars or nightclubs, I wonder? Not many perhaps, which would be a pity so far as their getting to hear about “Raising the Bar” is concerned. This is a detailed, thorough, academic study of the attempts that have been made to reduce alcohol-related violence in or just outside bars and nightclubs. Just that. No wonder as to how the people found themselves to be in those bars, the worst for drink.

The world explored is almost entirely English speaking. Australia predominates, reflecting the nationality of one of the authors; the other author being Canadian, there is much examination of attempts there to examine the causes of the violence there and in the US.

There are reports carried out of the work reported by British authors, particularly Philip Hadfield. A few references to Iceland and Sweden. My reaction is not that the authors have done a sloppy job in being so restrictive in their coverage but that it accurately represents the parts of the world where you might expect to see alcohol-related violence around bars. I am not suggesting that there isn’t excessive drinking in Russia and North Germany and perhaps Holland but I can’t recall hearing it being associated much with violence.

The Metropolitan Police kindly asked me to meet one of the authors two years ago and I mentioned to him, over dinner at Scotland Yard, the study done by Hall and Winlow, ‘Violent Nights’ 2006, which tried to understand why alcohol is so associated with violence in this country. No reference is made to it in this but I kept thinking back to ‘Violent Nights’ as I read ‘Raising the Bar’.

Why is it that there is so strong an association with violence and alcohol in some countries? Hall and Winlow’s thesis was that a section of English people choose to establish their role in society by the way in which they handle themselves in these licensed premises – these were sought out arenas, selected with the expectation of an opportunity to pick a fight with a stranger. It seems generally accepted that the first result of drinking alcohol is a lessening of inhibition. Why does that lead to animated conversation and laughter in so many countries and to mindless violence among certain English speaking (on the whole) men?

Raising the Bar can be thoroughly recommended to anyone responsible for stopping violence in a particular place. e.g.: Don’t give the opportunity for people to bump into people or furniture, train not only the door staff but all the other staff – servers, security, shot dispensing girls and DJs to create an ordered environment in which people do not get excessively drunk and in which good-order obviously reigns. Know how to get rid of the people who are not prepared to accept this.

But what happens when they get outside? What, indeed, would happen if every alcohol-led establishment was closed? (There is an interesting question posed here about the closing of skid row types of bars and pubs where getting drunk was generally accepted. Did their patrons stop drinking when the premises got shut down or did they, as both I and the authors believe, become the street-drinkers who now dominate so much of the expressed concern of people living in crowded cities. I am inclined to agree that they were safer and less trouble in their original environment.)

In my work as Licensing Chairman in an inner city, ‘Raising the Bar’ gives me the confidence to insist that bars and clubs must find ways to deter violence as there are detailed accounts of what has proved successful. Of course, I know I’m really just saying ‘don’t come to Westminster if you want to behave like that’. However, I am also currently involved in helping the City develop its second edition of its Alcohol Strategy, working across partnership with a wide set of agencies, particularly the social services and the Primary Care Trust. Does ‘Raising the Bar’ help me to do that? Well, I’m grateful for its confirmation that relying on spotting who is getting drunk in large premises is so incredibly difficult, particularly in areas like my own where residents are outnumbered four to one, that it’s hardly worth attempting. So much of popular expectation is built round models based on the Bull and the Vic. The reality is dark, very noisy places where you can’t speak to your friends and you have to keep drinking because there’s nowhere to put your glass down.

The book didn’t mention smoking. The smoking ban, together with job losses and the cheap price of supermarket alcohol fuel reports of diminishing attendance in clubs and pubs and may contribute to a lessening of nuisance for city residents. I can only hope that they won’t lead to a transfer of alcohol related violence and the establishment of macho values being even more common in people’s homes. Just think of the extra extent by which children would be exposed…..

Raising the Bar Preventing aggression in and around bars, pubs and clubs

Kathryn Graham (Centre for addiction and Mental Health, Ontario

Ross Homel (Griffith University)

Willan Publishing – Crime Science Series ISBN-10: 1-843923-18-1 ISBN-13: 978-1-84392-318-3 Published September 2008

Substance misuse in psychiatry – a guide for lawyers

By Bala Mahendra Reviewed by Jonathan Goodliffe, Solicitor

The author of this book is a consultant psychiatrist who is also qualified as a barrister. He regularly contributes to legal as well as medical journals and acts as an expert witness. This excellent book covers wide ranging medical and substance misuse issues. In legal terms the emphasis is on family and criminal law, although other subject areas such as contract and employment law are also considered.

This is not, however, just a book for lawyers. It is as good an introduction and overview as I have ever seen to the subject of substance misuse, with more emphasis than usual on the relationship between misuse and psychiatric disorders.

There is a detailed general introduction and a glossary for difficult expressions. There are then separate chapters on the leading drugs (other than nicotine) covering clinical, behavioural, assessment, management and prognosis issues, as well as medico-legal considerations.

The longest chapter (40 pages) is on alcohol. It contains, among other things, a balanced consideration of conflicting theories.

The style of this book makes for interesting and stimulating reading. This is partly because it challenges the lay reader to understand the clinical issues and how they relate to the behavioural side of substance misuse. It also considers, in layman’s language, some of the finer points which arise in the law. One of the reasons I find it valuable is because my own interest in the subject has tended to be focused on alcohol. I am conscious that the study of problems relating to alcohol should recognise the wider drug context and that people are increasingly misusing more than one substance.

There are many insights and throw away lines in this book that have a wider interest. For instance the author refers to a Court of Appeal judgment (R v Mental Health Act Commission ex parte X (1988) 9 BMLR 77) on the Mental Health Act 1983. It may also be relevant to the interpretation of substance misuse exclusion clauses in insurance policies.

On the subject of cocaine, the author remarks:

‘It has been suggested – with little by way of any hard evidence emerging – that upheavals which are a periodic feature in financial markets are occasionally due to a single trader or a group of these who have been emboldened in undue risk-taking by the intake of illicit substances, in particular cocaine, rumoured to be the substance of choice in the City of London and other financial centres.’

Could the lack of hard evidence relate to the difficulty of investigating the subject and the fact that it has not been a sufficiently popular focus of evidence based research? Or should the lack of evidence be taken to suggest that the proposition is unfounded? If one were to expand the area of enquiry from financial markets strictly speaking into banking and insurance, would cocaine rather than alcohol really emerge as the primary substance of choice? The financial downfall of Robert Maxwell, for instance, as well as his ultimate death, may have had at least something to do with his very heavy drinking.

‘Substance misuse in psychiatry – A guide for lawyers’ ISBN13: 9781846611476 Published by Jordan Publishing Ltd, £50 (discounted to £47.50 on Amazon). By Bala Mahendra

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

Gambling industry harms and parallels with the alcohol world

Will Prochaska –

Coalition to End Gambling Ads