In this month’s alert

Further support for minimum alcohol pricing

Research from the University of Sheffield, published in the medical journal The Lancet, provides further evidence that increasing alcohol prices could reduce illnesses, premature deaths and healthcare costs.

Dr Robin Purshouse and colleagues from Sheffield University’s School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR) and Department of Economics modeled the effects of alcohol pricing and promotion policy options for England, including:

- across-the-board price increases

- policies setting a minimum price per unit between 20p and 70p

- policies restricting price based promotions in the off-licensed trade sector, ranging from prohibiting large discounts only, through to a complete ban

Population subgroups such as hazardous drinkers aged 18–24 years, harmful drinkers, and moderate drinkers were analysed and the researchers found that, if a minimum cost of 50p per unit were introduced, this could result in:

- 2,900 less premature deaths per year within 10 years 41,000 fewer cases of chronic illness

- 8,000 fewer injuries each year

- 92,000 fewer hospital admissions per year

- a saving to the healthcare system in England of £270 million each year

For a minimum unit cost of £0.40, the estimated effects are projected as:

- 1,200 less premature deaths per year within 10 years

- 17,000 less chronic and 3,000 less acute cases of illness

- 38,000 fewer hospital admissions

- a healthcare system saving in England of £110 million

The authors found that harmful drinkers are affected considerably more than moderate drinkers by minimum price policies. For a 50p minimum price, a harmful drinker will spend on average an extra £163 per year whilst the equivalent spending increase for a moderate drinker is £12. This targeted effect arises because harmful drinkers purchase more of the cheap alcohol that is affected by a minimum price policy.

A 50p minimum price would prevent 49,000 cases of illness within 10 years, about 30,000 of which would be in men. Most of the harm reductions arise in chronic disorders in people aged 45 years and older, including diseases of the circulatory system, alcoholic disorders and alcohol-related acute outcomes, including road traffic accidents and falls.

The research also identified patterns of purchasing. Purchasing preferences vary across the population, with women purchasing a higher proportion of their alcohol from off-trade outlets (supermarkets and off-licenses) than men, and people aged 18–24 years purchasing alcohol mainly in the on-trade sector (pubs, bars and clubs). Beverage preferences vary; beer and wine comprise about three-fifths of the alcohol consumed by men and women respectively, and adult consumption of ready-to drink beverages (alcopops) is low relative to other types of drink, peaking at 20% of total consumption for women aged 18–24 years.

Consumption patterns also vary. Moderate male drinkers (excluding abstainers) consume on average about 8 units per week and only a small proportion engage in heavy episodic drinking, whereas harmful male drinkers consume on average 80 units and 7 in 10 are heavy episodic drinkers. Male harmful drinkers incur the largest proportion of alcohol-attributable mortality, ill health, alcohol attributable admissions, and healthcare costs.

Of the other pricing policies considered, the authors say:

“Prohibition of large discounts (for example buy-one-get one- free offers) alone has little effect, but tight restrictions or total bans on off-trade discounting could have effects similar in scale to minimum price thresholds of 30p–40p. For young adults, and especially for those aged 18–24 years, who are hazardous drinkers, policies that raise the price of cheaper alcohol in the on-trade sector (pubs and clubs) are most effective for achievement of harm reductions.”

The authors concluded: “General price increases are effective for reduction of consumption, healthcare costs, and health-related quality of life losses in all population subgroups. Minimum pricing policies can maintain this level of effectiveness for harmful drinkers while reducing effects on consumer spending for moderate drinkers. Total bans of supermarket and off-license discounting are effective but banning only large discounts has little effect. Young adult drinkers aged 18–24 years are especially affected by policies that raise prices in pubs and bars. Minimum pricing policies and discounting restrictions might warrant further consideration because both strategies are estimated to reduce alcohol consumption, and related health harms and costs, with drinker spending increases targeting those who incur most harm.”

Failure to in introduce minimum alcohol price the government’s “biggest health failing”

The Government’s rejection of the idea of setting a minimum price for a unit of alcohol was described as the biggest disappointment of his term of office by Sir Liam Donaldson, who is soon to retire as the Government’s Chief Medical Officer.

Sir Liam made the comment in an interview reported in the Daily Telegraph ahead of the publication of his final annual report on the state of the public health. In his previous annual report he had said that supermarkets and shops should not be allowed to sell alcohol for less than 50 pence per unit.

However, Prime Minister Gordon Brown rejected the proposal immediately, saying the “sensible majority” of moderate drinkers should not be punished for the excesses of binge drinkers.

Sir Liam’s proposal has the backing of most of the public health field and alcohol misuse agencies. The House of Commons Health Select Committee also supported the Chief Medical Officer against the Government, and the Scottish Government has been trying to introduce minimum pricing north of the border.

Sir Liam said the rejection of his proposal had been his greatest disappointment during his 12 years in post. The majority of his most important recommendations – including a ban on smoking in workplaces, allowing embryonic stem cell research, and changes to the way doctors are regulated – have been introduced.

Asked about recommendations where action had not been taken, and which of those he was most concerned about, Sir Liam said that on the public health front it would have to be minimum alcohol pricing. He added that, while he still hoped it would come in at some point, he had little hope of either of the main political parties changing their views on the matter in the short-term, saying: “I think we have to wait until after the election – there’s a lot of momentum building in the public health community.”

Government “too close to drinks industry”

MPs’ report calls for radical overhaul of alcohol policy – but Government rejects main recommendations

The drinks industry and supermarkets hold more power over government alcohol policies than do expert health professionals, according to the All Party House of Commons Health Select Committee.

In an eagerly awaited report published in January 2010 after a year’s investigation, the Committee concluded that the drinks industry is dependent on hazardous and harmful drinkers for three quarters of its sales and that if people drank ‘responsibly’, alcohol sales would plummet by 40%.

The Committee went on to make a series of recommendations including the introduction of minimum pricing, a rise in the duty on spirits and industrial white cider, tighter and totally independent regulation of alcohol promotion, vastly improved alcohol treatment services, better early detection and intervention, a mandatory labeling scheme for alcoholic drinks, and much better use of expert advice.

The report flatly rejected as a myth the suggestion that minimum pricing would unfairly affect moderate drinkers. It stated that at 40p per unit it would cost a moderate drinker (6 units per week) only 11p per week more than at present, and a woman drinking the maximum 15 units per week could buy her weekly total of alcohol for six pounds.

However, in its response to the Select Committee report, the Department of Health rejected some of its main recommendations, while insisting that other measures called for by the Committee were in fact already in place.

Don Shenker, Director of Alcohol Concern, condemned the Department’s response as complacent. He said:

“Whilst change cannot happen overnight – it certainly won’t happen if the government does nothing. Action on pricing, advertising and irresponsible promotions are the first step to reversing a drinking culture which has brought us to a point where average levels of teenage drinking is the equivalent of twelve and a half shots of vodka a week. The drinks industry will be delighted that Government are not planning any further action to independently monitor or regulate their practice.

“Health professionals, police officers and youth workers up and down the country will be very disappointed that another chance to take further action on reducing alcohol harms has gone missing, leaving them to clean up a mess the government is unwilling to tackle.”

Select Committee Report

Launching the Select Committee report, Kevin Barron MP, the Chairman of the Committee, said:

“I agree with the Chief Medical Officer that introducing unit pricing will reduce binge drinking. As the report points out, it will also help traditional pubs in their battle against cut price supermarket offers.

“The facts about alcohol misuse are shocking. Successive governments have failed to tackle the problem and it is now time for bold government.

“Even small reductions in the number of people misusing alcohol could save the NHS millions. What is required is fundamental cultural change brought about by evidence-based policies; only this way are we likely to reduce the dangerous numbers of young people drinking their lives away.”

The report urged the duty on spirits to be returned in stages to the same percentage of average earnings as in the 1980s (11%) and a lower duty on weak beer.

Early detection and intervention, the Committee concluded, are important in both health and financial terms and the report recommended these could easily be built into existing initiatives, but first of all the current dire state of alcohol treatment services had to be addressed.

Health information, the Committee agreed, was important but did not change actual behaviour, and the government spend of £17.6m on alcohol awareness for 2009/10 was far outweighed by the £600-800m spent by the drinks industry promoting alcohol.

The report also calls for the ‘feeble’ licensing and enforcement regime to be strengthened.

Not surprisingly, spokesmen for the alcohol control and public health organizations expressed strong support for the Select Committee’s recommendations.

For the British Medical Association, Dr Vivienne Nathanson said:

“We are pleased that the Committee agrees that the drinks industry and supermarkets exert too much power over government alcohol policies. This cosy relationship needs to end and we need radical action to tackle alcohol misuse including minimum pricing, higher taxation, reduced availability, improved regulation and better treatment for patients who have alcohol addiction problems.

“At a time when the NHS is facing cuts, it is shocking that every year millions of pounds are spent treating patients for the illness and violence that goes hand in hand with alcohol misuse. A reduction in alcohol misuse would free these valuable resources for other life-prolonging treatments.

“The government needs to wake up and realise that society has an unhealthy relationship with alcohol and that this will not change while politicians refrain from bringing in tough new legislation but prefer to keep the drinks industry happy.

” Equally predictably, spokesmen for the alcohol industry disagreed. Seymour Fortescue, Chairman of the industry’s Portman Group said:

“We agree that alcohol-related harm is increasing, despite the fact that there has been a drop in total consumption over the past five years. This suggests that measures must be targeted at the minority of drinkers who abuse alcohol rather than the responsible drinking majority.

“We acknowledge the views of the medical profession and some politicians that there should be a minimum price for alcohol. However, there are real concerns as to whether this will work. The responsible majority of drinkers will pay more and hard core drinkers may not be deterred. It would also take money from poorer people and transfer it to the supermarkets – a curious piece of social justice.

“A fairer and more effective approach focuses on dependent and binge drinkers. We can influence the irresponsible minority through better education and effective law enforcement.

” Simon Litherland, managing director of Diageo GB, was more combative. He described the Select Committee’s recommendations as “draconian”, and said that they lacked a credible evidence base and were likely to have serious repercussions for the media and advertising industries.

Litherland claimed the MPs’ report represented “yet another attempt by aggressive sections of the health lobby to hijack alcohol policy-making”, adding “It seeks to marginalise the role of industry in helping to tackle the problem of alcohol misuse.

” In its statement, the Advertising Standards Authority commented: “The UK’s advertising regulatory regime for alcohol is one of the strictest in the world. The ASA regularly upholds complaints against major companies, demonstrating that the mandatory Codes are strictly applied.”

The Government’s Response

The Department of Health rejected the call for a further crackdown on alcohol advertising and promotion, saying that the policy of self– and co-regulation and education was working well. It also said that, contrary to the Committee’s recommendations, sponsorship and the majority of new digital media are already covered by the existing codes. However, the Department added that the Government will continue to monitor the effectiveness of the UK’s regulatory regime, especially in relation to new media, and it promised to commission, jointly with other Departments, a review of current evidence on harm to children and young people from alcohol advertising, promotion and sponsorship.

On a minimum price for alcohol, the Department left the decision open until more research on the strategy’s effect on crime and disorder has been collected.

In regard to alcohol licensing, the Department rejected the Committee’s recommendation – one supported by most of the public health and alcohol misuse lobbies – that the Licensing Act governing England and Wales should be amended to include a public health objective, as is included in the equivalent Scottish legislation. While the Department agreed that the Government should monitor the impact of the Scottish legislation, it pointed out that the English and Welsh Licensing Act covers all licensable activities, not just the provision of alcohol, and it was not clear that it was reasonable to impose an overriding objective on late night takeaways, restaurants, live music events, cinemas and such like to promote the health of their patrons, nor clear how they would be able to give effect to such an objective.

Obituary – Professor Brian Prichard CBE

We regret to report the death of Professor Brian Prichard, the Chairman of the Institute of Alcohol Studies from its foundation in 1981.

We regret to report the death of Professor Brian Prichard, the Chairman of the Institute of Alcohol Studies from its foundation in 1981.

Professor Prichard qualified in medicine at St George’s Hospital and became a consultant physician. Later he became Emeritus Professor of Clinical Pharmacology.

Born in Wandsworth, he was first elected to Wandsworth Council in 1964, and in 2009 became the fourth member of his family to take up the post of Mayor in south west London. Professor Prichard was a founder member of the Conservative Medical Association.

He was awarded the CBE in 1996.

Industry documents ‘reveal the truth about alcohol advertising’

Although the content of alcohol advertisements in the UK is restricted, an analysis of previously unseen industry documents published by the British Medical Journal finds that advertisers are still managing to appeal to young people and promote drinking.

Professor Gerard Hastings and colleagues show that companies are “pushing the boundaries” of the advertising code of practice and warn that the UK system of self regulatory controls for alcohol advertising is failing.

Hastings and his team analysed a sample of internal marketing documents from four alcohol producers and their communications agencies. The documents were made available as part of the House of Commons Health Committee alcohol inquiry and included client briefs, media schedules, advertising budgets, and market research reports.

The alcohol industry spends around £800m (€900m; $1.3bn) a year promoting alcohol in the UK.

The authors looked at four themes that are banned by the advertising code of practice, such as appealing to people under 18 and encouraging irresponsible drinking, as well as sponsorship and new media.

They found that market research data on 15 and 16 year olds is used to guide campaign development and deployment, while many references are made to the need to recruit new drinkers and establish their loyalty to a particular brand. WKD, for instance, wants to attract “new 18 year olds” and Carling takes a particular interest in the fact that the Carling Weekend is “the first choice for the festival virgin.”

Despite a ban on encouraging drunkenness and excess, the authors also found many references to unwise and immoderate drinking, suggesting that increasing consumption is a key promotional aim.

Other documents suggest that brands can promote social success, masculinity or femininity, despite this also being banned under advertising codes. For example, Carling is described as a “social glue” by its promotion team, while the need to “communicate maleness and personality” is noted as a key communications objective for WKD.

Although the codes prohibit any link between alcohol and youth culture or sporting achievement in advertising, the documents discuss in detail sponsorship deals with football, lads’ magazines, and music festivals. The use of new media, including social networking sites, is also a fast growing channel for alcohol advertising, say the authors.

Hastings and his team argue that the UK needs to tighten both the procedures and scope of the regulation of alcohol advertising.

They suggest that regulation should be independent of the alcohol and advertising industries and that all alcohol advertisements should be pre-vetted. And they call for sponsorship to be covered by the regulations, and much greater scrutiny for digital media. Particular efforts should also be made to protect children from alcohol advertising, they say, such as banning billboards and posters near schools and restricting TV, radio and cinema advertisements.

They believe that the current problems with UK alcohol promotion are reminiscent of those seen before tobacco advertising was banned, “when attempts to control content and adjust targeting simply resulted in more cryptic and imaginative campaigns.

“History suggests that alcohol advertisers are, appropriately enough, drinking in the last chance saloon” they conclude.

In reply, David Poley of the alcohol industry’s Portman Group said:

“We are proud of the regulatory system for alcohol in the UK which is admired across the world. Gerard Hastings trawled through thousands of pages of internal company marketing documents on behalf of the Health Committee. He failed to find any evidence of actual malpractice. He therefore resorts to slurs and innuendos. We wish Gerard Hastings would publish his criticisms in an advertisement. The ASA could then rightly ban it for being misleading.”

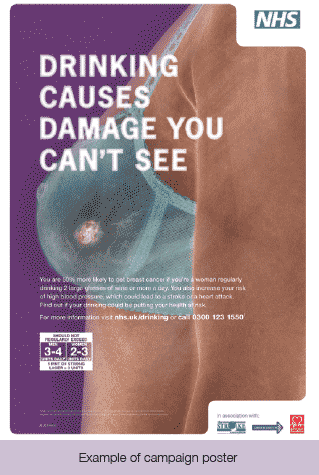

New NHS campaign reveals unseen alcohol damage

A new health education campaign to warn drinkers of the unseen health damage caused by regularly drinking more than the NHS advises has been launched by the Government. The £6 million campaign shows the damage being done to drinkers’ organs while they are drinking in a pub or at home. The campaign was launched by Public Health Minister, Gillian Merron as part of the cross-Government strategy to tackle the harms that alcohol causes.

The Department of Health developed the campaign in association with Cancer Research UK, the British Heart Foundation and the Stroke Association to create the series of ‘stark’ TV, press and outdoor adverts showing the harm that regularly drinking more than two drinks a day can cause.

A new YouGov poll, launched to coincide with the campaign, showed that more than half (55%) of English drinkers misguidedly believed that alcohol only damaged their health if they regularly got drunk or binge drank. The survey, of over 2,000 adults, also found that 83% of those who regularly drank more than the NHS recommended limits of 2-3 units a day for women (about two small glasses of wine) and 3-4 units a day for men (about two pints of lager) did not think their drinking was putting their long-term health at risk.

With 10 million adults in England estimated to be drinking above the recommended limits, this is equivalent to around 8.3 million people potentially unaware of the damage their drinking could be causing.

Although 86% of drinkers surveyed knew that drinking alcohol is related to liver disease, far fewer realised it is also linked with breast cancer (7%), throat cancer (25%), mouth cancer (28%), stroke (37%) and heart disease (56%), along with other serious conditions

Public Health Minister, Gillian Merron said:

“Many of us enjoy a drink – drinking sensibly isn’t a problem. But, if you’re regularly drinking more than the NHS recommended limits, you’re more likely to get cancer, have a stroke or have a heart attack.

Gillian Merron MP Public Health Minister www.ias.org.uk 6 Alcohol Alert Spring 2010

“With alcohol misuse damaging so many people’s health and lives, the Government has teamed up with Cancer Research UK, the British Heart Foundation and the Stroke Association to produce this straight talking campaign. It’s important to show drinkers the unseen damage alcohol can do to their body.”

Further information on the campaign can be found at: www.drinking.nhs.uk

Alcohol hospital admissions continue to climb

Alcohol-related admissions to NHS hospitals in England are continuing to rise, according to figures provided by The NHS Information Centre in reply to a Parliamentary Question by Mr James Brokenshire MP.

It is estimated that around 6% of all NHS admissions are alcohol related, and that alcohol related admissions have been increasing by approximately 80,000 every year.

The new figures show that there were 945,223 people admitted to hospital with an alcohol-related illness between 2008-09, compared to 644,185 in 2004/05, an increase of 38% (using rates of admission statistics per 100,000 population). The highest rates of admissions occurred throughout the period in the North East and the North West Strategic Health Authorities.

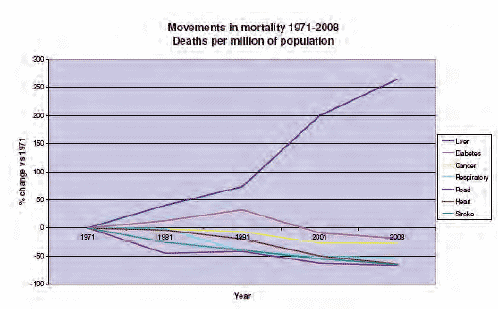

Liver disease deaths increase by 12% in just three years

Government mortality statistics for the UK show that deaths from liver disease continue to rise, increasing by 12% in the last three years, totalling 46,244 lives lost. In 2008, liver disease killed 16,087 people – a 4.5% increase from 2007. If these rates continue, deaths from liver disease are predicted to double in 20 years.

The graph below was produced by the British Liver Trust to illustrate the true extent of liver disease in the UK. It shows that liver disease, when compared to the other five big causes of death, is the only one showing a steady increase year-on-year.

Alison Rogers, Chief Executive of the British Liver Trust, said:

“Once again we are seeing the tide of liver disease rising further and putting a huge strain on the NHS. The sad fact is that 95% of all liver disease is entirely preventable.

” A comparison to figures published four years ago shows that there has been a 26% increase in people under the age of 25 dying from alcoholic liver disease in England and Wales. In 2006, 161 young people died compared to 2004 when 122 died.

“This is an alarming trend, particularly when you consider that alcoholic liver disease typically takes up to ten years to develop. This means that young people are putting their liver health at increased risk from a very young age.

Over nine million people in England could benefit from brief advice

Over 9 million people in England drink more than is good for them, but many don’t even realise that the way they drink could put their health at risk.

” So commented Dr Mike Knapton, GP and Associate Medical Director at the British Heart Foundation, in relation to research which concluded that consumption for higher risk drinkers can be reduced to lower risk levels with increased use of alcohol identification and brief advice (IBA) delivered by healthcare professionals.

The research involved focus groups and field work in London and the South West, with nurses, GPs and A & E staff, which was carried out as part of the Government’s ‘Alcohol Effects’ campaign. The campaign, launched in February 2010, aims to warn drinkers of the unseen health damage caused by regularly drinking more than the NHS advises. Increasing and higher risk drinking can cause unseen damage and are implicated in the development of more than 60 medical conditions, ranging from cancer to liver disease and stroke. Using IBA, health workers can help patients understand how their drinking affects their health in the long and short term.

Dr Knapton continued:

“As we have seen with smoking, brief interventions, as part of a wider strategy, can have a significant impact on helping to raise awareness of the health risks associated with alcohol and in bringing about a change in behaviour. A short GP consultation is more than adequate to carry out identification and brief advice to identify those that are drinking at increasing and higher-risk levels and provide them with some simple advice for cutting down. Health care professionals’ knowledge of the dangers that can be caused by regularly drinking too much alcohol is vital to this process, as is reinforcing the positive effects GPs and nurses can have on a patient’s health by talking to them about their drinking habits.’”

Professor Ian Gilmore, President of the Royal College of Physicians said: “IBAs really work, and are up there with some of the most effective interventions that are available to us in healthcare. Many healthcare workers don’t realise that IBAs for harmful drinkers are even more effective than current interventions for smoking. Let’s take every opportunity to reduce this preventable burden of health harm.”

The IBA tools are quick and simple to use and not only identify accurately patients’ levels of risk in relation to their drinking, but help those drinking at increasing and higher risk levels to recognise the potential risk and cut down. Drinkers are prompted to reconsider their behaviour and encouraged to reduce their consumption to lower risk levels. A range of materials have been developed to assist with the delivery of IBA, including factsheets, leaflets, questionnaires and an e-learning module endorsed by the Royal College of Nursing and the Royal College of Physicians, accredited by the RCN Accreditation Unit and required as preparation for the RCGP post-graduate certification course on alcohol management.

The module takes less than two hours to complete and provides the information and skills required to deliver IBA, including details on units and the risks associated with alcohol consumption.

The module and other materials are available at: www.alcohollearningcentre.org.uk

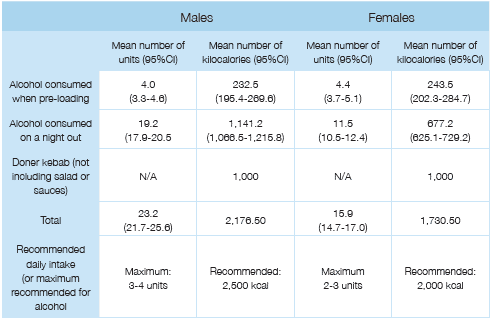

Alcohol and food – tackling ‘the kebab effect’

The need to link public health policies on alcohol with those on food has been highlighted by a new report from the Public Health Unit at John Moores University.

Despite obesity and alcohol being two of the biggest threats to public health, people are often unaware, the report says, of the health links between food and alcohol, with little or no public information on how alcohol consumption affects food cravings, whether eating reduces drunkenness, and how both eating and drinking in excess increase risks of developing major diseases. The new report explains how the two areas of concern are, in fact, intertwined in a range of ways, and not just in the obvious one that alcoholic drinks contain large numbers of calories.

Many people are likely to have multiple behavioural health risks linked to obesity, smoking and alcohol behaviours which, together, are likely to reinforce and accelerate each other’s contributions to illness and premature death related to cardiovascular disease, cancer and liver disease in the UK. Indeed, food and alcohol problems may have similar roots, in that poor education and negative childhood experiences have been linked to low levels of physical activity, obesity and alcohol problems in later life.

The authors identify nightlife as a particularly important context for combined food and alcohol issues. For example, while food in the stomach may delay absorption of alcohol, and hence reduce drunkenness, drinking alcohol can affect levels of hunger and food preferences, and consumption may increase preferences for fatty and high sugar foods, with such cravings contributing to risks of obesity, what the authors term ‘the kebab effect’.

In a recent survey of English drinkers aged 18-35 years, a substantial proportion reported eating crisps or nuts, which, being salty, are likely to increase thirst and hence alcohol consumption, whilst others reported consuming pizzas, burgers, chips or kebabs when drinking more than two alcoholic drinks. The authors point out that in what would be considered a typical night out in this age group, people not only exceeded by a wide margin the recommended maximum consumption of alcohol, they also consumed, with food and drink combined, little short of the entire daily recommended maximum intake of calories.

The authors conclude that UK policy should address the links between alcohol and food in order to maximize the effectiveness of public health responses and to enable people to make healthier choices. This should include proper labeling of alcohol products. The UK population, they say, needs urgently to move away from seeing alcohol as a means to get drunk, towards a Mediterranean culture of seeing alcohol as an accompaniment to food, with both being consumed in moderation.

The publication, ‘Alcohol and Food – Making the public health connections’; Morleo, M; Bellis, M A; Perkins, C; Hannon, K L; Clegg, K; Cook, P A – January 2010, can be downloaded at: http://www.cph.org.uk/ publications.aspx

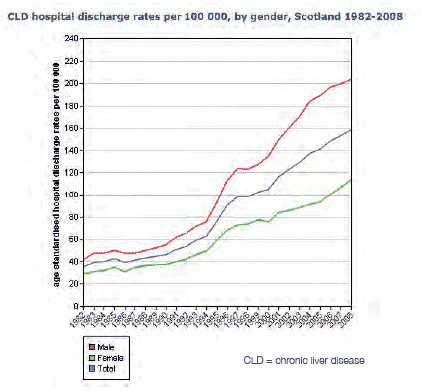

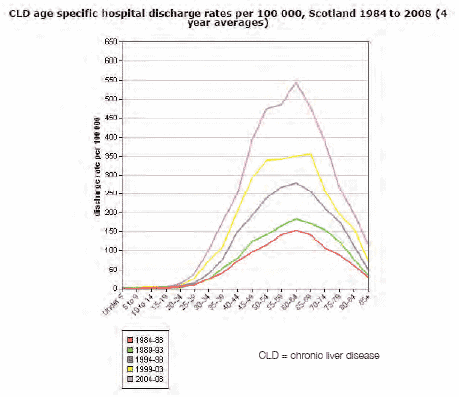

Scots under 40s risking serious health harm

Scotland’s culture of heavy and binge drinking is having an increasing impact on the health of younger people, according to the latest statistics. These also show that Scotland is bucking the international trend for chronic liver disease: while most European countries have seen levels fall, rates in Scotland have almost trebled over the last 15 years.

The latest Alcohol Hospital Statistics and Liver Disease Statistics show:

- Scotland sees, on average, 115 hospital discharges per day due to alcohol misuse

- Alcohol-related discharges have increased by nine per cent over the past five years

- Alcohol-related discharges have increased by 22 per cent for 30-34 year olds and by 19 per cent for 35-39 year olds

- Scotland’s rate of chronic liver disease almost trebled over the last 15 years – and continues to rise

- While death rates have been falling across most of Europe, they remain high in Scotland

- Chronic liver disease death rates amongst 30-39 year olds have risen almost five-fold since the mid 1980s

- Rates of hospital discharge for chronic liver disease among young Scottish women (25-29) has increased seven-fold over the last 20 years.

Health Secretary Nicola Sturgeon said:

“These shocking statistics make grim reading and provide yet more evidence that we must turn the tide of alcohol harm.

“Scotland’s love affair with drink is well documented and we’re taking radical and decisive action to tackle pocket-money prices which – as the World Health Organisation recognises – help to drive consumption and harm.

“Most worrying is the increase in alcohol-related problems among young people, who are putting themselves at risk of serious health problems. Alcohol is now around 70 per cent more affordable than it was in 1980 and, over the same period, consumption and alcohol-related harm have spiralled. These factors are not unrelated.

“Cheap alcohol is making a serious situation even worse. By linking price to product strength, minimum pricing will put an end to the sale of high-strength alcohol for less than the cost of bottled water.

“This will help to address the staggering cost to Scotland – both in economic terms and in terms of lost or blighted lives.”

Alcohol misuse is estimated to cost Scotland around £3.6 billion per year, or £900 for every adult.

Proposals to introduce a minimum price per unit of alcohol were included in the Alcohol Bill which is currently making its way through the Scottish Parliament.

Research clearly shows that the greatest effect of a minimum price would be on heavy and young drinkers, who tend to choose higher strength, lower-cost products.

Further information and data can be accessed at http://www.scotpho.org.uk/chronicliverdisease/

Scotland’s doctors call for end to supermarket ‘reward’ points for alcohol

Scottish GPs have backed a proposal that alcohol purchases should not be eligible for “customer loyalty points” as part of a series of measures to tackle the promotion of cheap alcohol in supermarkets. GPs attending the annual Scottish conference of Local Medical Committees in Clydebank also gave their unanimous backing to the Scottish Government’s plans for a minimum price for alcohol.

Speaking during the debate, Dr Catriona Morton, a GP in Edinburgh, said:

“Alcohol misuse doesn’t just affect the drinker, but also those around them. 65,000 Scottish children live in homes with problematic drinkers – the rate of calls to Childline Scotland from children distressed by alcohol use in their families is twice that of the rest of the UK. Most alcohol bought for consumption at home is from supermarkets. Supermarkets offer special cut price deals on alcohol and offer special promotions to encourage bulk buying of cheap alcohol. Stopping loyalty points – not available on cigarettes – would be a tiny reminder of unequivocal harm caused.”

Dr Jim O’Neil, a GP in Glasgow, added:

“I work in an area of deprivation in Glasgow where life expectancy for men is just 58. Alcohol is one of the biggest killers and cause of morbidity in my area. Local Government must also take responsibility when issuing licenses for corner shops who sell cheap alcohol.”

The Motion Debated was: That conference acknowledges the relationship between irresponsible alcohol promotions and problem drinking, and:

- commends the Scottish Government on its proposals to introduce legislation for minimum pricing per unit of alcohol

- insists that alcohol purchases should not be eligible for “customer loyalty points”

Young Scots’ youth commission on alcohol calls for a ban on alcohol ads in public places

Scotland’s first ever youth commission publishes recommendations to improve Scotland’s relationship with alcohol

Increased alcohol education within the school curriculum, a ban on alcohol advertising in public places, diversionary activities for adults and research into the impact of passive drinking are just some of the recommendations made by Scotland’s first Youth Commission on Alcohol. The findings from the year-long investigation looking into Scotland’s relationship with alcohol were formally handed over to Minister for Public Health, Shona Robison MSP.

Commissioned by the Scottish Government and supported by Young Scot, The Youth Commission on Alcohol, was launched in March 2009. It was fully led and carried out by 16 young people from all over Scotland who took a full sweep of society to make recommendations for policy and action to change Scotland’s culture of alcohol misuse.

The Youth Commissioners, all aged between 14 and 22, have, for the last year, been investigating the issues that contribute to Scotland’s alcohol consumption, shaping resolutions to the problem, and have now made recommendations for future change. There are 38 recommendations based around eight key work streams: accessibility and availability; changing culture through leisure and lifestyle choices; education; emotional support for young people; personal safety; regulating alcohol industry marketing and promotion; social marketing; and young people influencing treatment services.

Youth participation

After their experience in examining the issue of alcohol, the Commissioners have called for widespread participation of young people in policy and decision-making, at a local and national level, to be a fundamental factor in underpinning future cultural change in Scotland. Current levels of youth engagement in shaping and influencing elements of licensing decisions, designing leisure activities and social marketing campaign development, and planning education programmes require a stronger emphasis to meet the needs of not just young people but society as a whole.

Passive drinking

Many young people are negatively affected, not by their own drinking choices, but by those of others and the recommendations recognise the importance of raising awareness of passive drinking among young people and the support services available to them. The report identifies a gap in existing research into the impact of passive drinking on young people and adults.

Alcohol advertising

The recommendations tackle the impact of alcohol marketing and promotion, calling for a clear and realistic pathway to a complete ban of alcohol advertising in public places as a long-term goal. The aim is to reduce the amount of advertising people in Scotland are exposed to. Having studied the effects of alcohol promotion, the Commissioners stipulate that the public sector should clearly lead regulation of alcohol promotion and enforce stricter regulation of digital marketing campaigns.

Alternative leisure choices

One of the unique recommendations to address culture change is through action to encourage alternative alcohol-free leisure and lifestyle choices for adults. The alternative activities recommended in the report would create a positive leisure time culture among adults. Less emphasis on alcohol consumption will have a direct impact on the experience and understanding of alcohol young people take from their adult peers.

Education

The report also proposes that alcohol education should be given a greater focus in school education. By recognising ‘Health and Wellbeing’ as a school subject in its own right alcohol education will be embedded into existing strategies to give young people an improved knowledge and understanding.

During the course of the investigation the Youth Commissioners undertook an extensive research programme, participating in national conferences, consulting stakeholders, visiting experts, projects and key agencies to build up a significant body of evidence from which to make their recommendations. It is anticipated that following the formal handover, the recommendations – which have given a voice to Scotland’s young people – will be considered as part of the Scottish Government’s Framework for Action on Alcohol.

Youth Commissioner, Ryan Leitch said: “It was fantastic being involved with the Youth Commission on Alcohol. It’s great that young people have been given this opportunity to have their voice heard at the upper levels of government, hopefully there will be lots more commissions like this. We based our recommendations on the evidence we received from alcohol experts and the Scottish people. There isn’t one answer so we have come up with a number of key approaches to improve Scotland’s relationship with alcohol.”

Public Health Minister Shona Robison said: “Tackling alcohol misuse is a key priority for the Scottish Government and we recognise both the need to protect young people from this potential harm and the role they can play in tackling Scotland’s reputation as a nation of heavy drinkers. The Youth Commission on Alcohol has been a unique piece of work, and engaging with these young people will provide further input to our ongoing action.”

www.youngscot.org – The national youth information portal for Scotland www.youngscot.net – Young Scot’s corporate website

Alcohol and knives continue to kill Scots

Justice Secretary Kenny MacAskill complains that too many lives continue to be lost because of Scotland’s relationship with alcohol.

Newly released figures show that alcohol continues to be a conspicuous feature of a large proportion of homicides in Scotland.

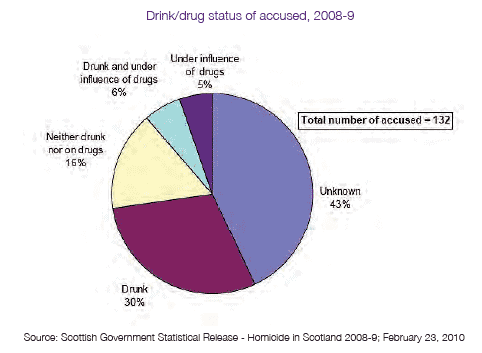

Despite there being a fall in the number of homicides in 2008-09, Mr MacAskill said that the fact that more than two out of five of those accused of homicide were drunk or on drugs – or a cocktail of both – showed that urgent action was required to deal with Scotland’s drinking culture. Drink/drug status of accused, 2008-9 Source: Scottish Government Statistical Release – Homicide in Scotland 2008-9; February 23, 2010

The figures, published by Scotland’s Chief Statistician, also show that knives or other sharp instruments were the cause of more than half of all killings in Scotland.

Mr MacAskill said:

“While fewer people were killed last year than in previous years, that is of no consolation to the families of the victims. And while we can’t turn back the clock, what we can do is work to make Scotland safer and stronger.

“These figures provide further depressing evidence of the toll that Scotland’s drinking culture is taking on this country. Indeed given that the perpetrator is not always apprehended immediately, the real figure for the number of killers who were drunk when they committed the crime is likely to be higher. The figures support the picture painted in last month’s prisoner survey, which showed that half of all prisoners were drunk at the time they committed the offence that saw them end up behind bars.

“So if we successfully tackle Scotland’s drinking culture we can significantly reduce the number of people who get caught up in violent crime. That is why we have outlined a package of measures to help reduce consumption and to encourage more responsible drinking, including minimum pricing to reduce consumption and harm.”

Alcohol harm ‘costs every Scot £900 per year’

Alcohol harm could be costing Scottish taxpayers around £3.56 billion per year, according to an independent study carried out by the University of York. The research, which looked at the impact across the NHS, police, social services, the economy and on families, estimated the total annual cost at between £2.48 billion and £4.64 billion – with a mid-point estimate of £3.56 billion. Averaged across the population, the £3.56 billion figure means alcohol harm could be costing every Scottish adult about £900 per year. Even the lowest figure is substantially higher than the previous estimate of £2.25 billion per year.

Alcohol harm could be costing Scottish taxpayers around £3.56 billion per year, according to an independent study carried out by the University of York. The research, which looked at the impact across the NHS, police, social services, the economy and on families, estimated the total annual cost at between £2.48 billion and £4.64 billion – with a mid-point estimate of £3.56 billion. Averaged across the population, the £3.56 billion figure means alcohol harm could be costing every Scottish adult about £900 per year. Even the lowest figure is substantially higher than the previous estimate of £2.25 billion per year.

- Using the mid-point estimate of £3.56 billion in 2007:

- Healthcare related costs were put at £268.8 million or 7.5 per cent of the total

- Social care costs were estimated to be £230.5 million or 6.5 percent of the total

- Crime costs were put at £727.1 million or 20.4 per cent of the total

- The cost to the productivity of the Scottish economy was £865.7 million or 24.3 per cent of the total

- The human cost in terms of suffering caused by premature deaths was £1.46 billion or 41.2 per cent of the total

Health Secretary Nicola Sturgeon said:

“This report, which takes a more comprehensive view than any previous study, indicates that the total cost of alcohol misuse to Scotland’s economy and society is even worse than we thought. Not only does alcohol misuse burden our health service and police it also has a terrifying knock-on effect on our economic potential and on the families devastated by death and illness caused by alcohol.

“The Scottish Government’s Alcohol Bill includes a package of evidence-based measures to get to grips with this issue, including minimum pricing to combat the dirt cheap ciders, lagers and low-grade spirits favoured by problem drinkers.

“It is supported by a broad coalition including the four Chief Medical Officers of the UK, the British Medical Association, the Royal Colleges, Church of Scotland, Association of Chief Police Officers of Scotland and the Scottish Licensed Trade Association. And on Friday, the House of Commons Health Committee also came out in favour of minimum pricing.

“The time for stalling is over and the need for action is clear. I call on all MSPs to do the right thing and support the measures in the Alcohol Bill.”

The Scottish Government introduced its Alcohol Bill to Parliament in November 2009. Its proposals include:

- A minimum price per unit of alcohol to raise the cost of the cheapest ciders, lagers and low-grade spirits favoured by problem drinkers

- A ban on irresponsible off-sales promotions which encourage excessive drinking

- A duty on licensing boards to consider raising the off-sales purchase age to 21 where appropriate to develop local solutions to local problems

- A power to introduce a ‘social responsibility fee’ on some retailers to offset the costs of dealing with drink problems

The Scottish Government has committed investment of almost £120 million over the period of the spending review (2008-11): the single largest increase ever for tackling alcohol misuse in Scotland, and almost a tripling in resources.

Irresponsible drinks promotions banned – or at least some of them

Drinks promotions defined as irresponsible, including “all you can drink for £10” and “dentist chairs” were banned from the beginning of April 2010 under the new Mandatory Code on the selling of alcoholic drinks. Other restrictions are scheduled to come into force on 1 October 2010 to give retailers time to prepare.

However, critics of the Code complain that there is confusion and uncertainty regarding what exactly is banned and what is still permissible, with licensing authorities having partial discretion to decide what counts as ‘irresponsible’, and, it is claimed, the guidance on the interpretation of the Code given by the Home Office partially contradicting that given by the Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS).

The power to introduce a Mandatory Code of conduct for alcohol retailers was granted through the Policing and Crime Act which received Royal Assent in November 2009. Launching the Code, Home Office Minister Alan Campbell said:

“Alcohol-related crime costs the UK billions of pounds every year and while the vast majority of retailers are responsible, a minority continue to run irresponsible promotions which fuel the excessive drinking that leads to alcohol-related crime and disorder.

“The code will see an end to these promotions and ensure premises check the ID of those who appear to be underage helping to make our towns and city centres safer places for those who just want to enjoy a good night out.”

Premises found to be in breach of the Code or any secondary conditions that have been imposed will face a range of possible sanctions including losing their licence, having additional conditions imposed on their licence or, on summary conviction, a maximum £20,000 fine and/or six months imprisonment.

The conditions that have already come into force are:

- banning irresponsible promotions such as “all you can drink for £10” offers, women drink free deals and speed drinking competitions

- banning “dentist’s chairs” where drink is poured directly into the mouths of customers making it impossible for them to control the amount they are drinking; and

- ensuring free tap water is available for customers – allowing, it is suggested, perhaps somewhat optimistically, people to space out their drinks and reduce the risks of becoming dangerously drunk

The remaining conditions scheduled to come into effect on 1 October are:

- ensuring all those who sell alcohol have an age verification policy in place requiring them to check the ID of anyone who looks under 18 to prevent underage drinking which can lead to antisocial behaviour and put young people at risk of harm;

- and ensuring that all on trade premises make available small measures of beers, wine and spirits to customers so customers have the choice between a single or double measure of spirits and a large or small glass of wine

Confusion and uncertainty

Critics of the Code were quick to point out that some of its provisions are ambiguous, and that there does appear to be some lack of consistency between the interpretations of the Code provided by different government departments.

For example, the Guidance issued by DCMS to the operation of the Licensing Act, amended to take account of the new Code, states that the Code prevents the sale of ‘unlimited or unspecified quantities of alcohol free or for a fixed or discounted price’, such as ‘drink as much as you like for £10’. The DCMS Guidance goes on to say that “this restriction does not mean that promotions cannot be designed with a particular group in mind but a common sense approach is encouraged, for example, by specifying the quantity of alcohol included in the promotion”.

In contrast, the Guidance issued by the Home Office states that among the promotions that are banned are those such as ‘10 pints for £10’, which clearly do specify the quantity of alcohol included. Presumably, the answer in this particular case is that 10 pints of beer are regarded as sufficient to cause drunkenness, and hence to be in potential breach of the objectives of the Licensing Act. However, problems of interpretation might arise in relation to promotions offering lesser quantities.

Drink drive limit to be issue for new Government

Whichever political party wins the general election will have to make a decision on whether to lower the legal alcohol limit for drivers.

At the end of 2009, transport minister Lord Adonis asked Sir Peter North to conduct a review of the evidence in regard to drink and drugged driving. For drink driving, the Review will advise on the case for changes to the prescribed alcohol limit for driving – such as reducing the current limit, or adding a new, lower limit, with an associated revised penalty regime.

The review was originally intended to be completed by the end of March 2010, and Lord Adonis was given Sir Peter’s provisional conclusions by the appointed date. However, a final report is still in process of being drawn up, and this will now be submitted to whoever is the Secretary of State for Transport following the general election and the formation of a new government.

Influence of parents on children’s alcohol decisions recognised

The Government has introduced new measures to increase parents’ confidence in talking to their children about alcohol. This follows the publication of ‘Children, Young People and Alcohol’, a research report for the Department for Children, Schools and Families, which demonstrates the influence of parents on their children’s relationship with alcohol.

The research results show “the huge importance of the parent’s role in educating their child about alcohol – parents were most likely to introduce alcohol to their children in their own homes, to set the rules and guidelines for drinking and the large majority of young people would go to their parents first for more information or advice about alcohol”. 97% of parents questioned said they would feel comfortable discussing the risks of alcohol with their children and “the majority of parents said that they would be proactive in dealing with the issue of alcohol and their child, and 90% agreed that it is up to them to set a good example through their drinking…89% of parents said that they were confident that the things they have done would help their child to have a safe and sensible relationship with alcohol.”

The research follows the Chief Medical Officer’s (CMO) Guidance, issued in January 2009, which gave parents a central role in helping to form their children’s relationship with alcohol – an importance which many parents may underestimate. The CMO advised that this importance should be communicated to parents, carers and professionals, together with advice on how to respond to alcohol use and misuse by children. In the research, parents were asked about their awareness of the Guidelines and their content. “One in three parents (34%) said that they had heard of the ‘official guidelines or limits for sensible drinking for young people aged under 18’. However, amongst those who had heard of the Guidelines, very few said that they know much about them. While one in eight (12%) of parents aware of the Guidelines said that they know a lot, a quarter said that they had just heard of them.”

The CMO’s advice also stated that:

whilst an alcohol-free childhood is desirable, if young people aged 15-17 years old do drink alcohol it should always be with the guidance of a parent or carer or in a supervised environment parents and young people should be aware that drinking can be hazardous to health and that not drinking is the healthiest option for young people

children aged 15-17 who are drinking, should do so infrequently and certainly on no more than one day a week and they should never drink more than the adult daily limits recommended by the NHS

support services must be available for children and young people who have alcohol-related problems and for their parents. (The research found that ‘Detailed information about young people and alcohol, including information on the facts around alcohol (e.g. number of units in drinks) and about the dangers of alcohol to young people, were most commonly mentioned by parents as useful to them, or to make them feel more confident about their strategies with their child.’)

The Government’s new measures, aimed at tackling underage drinking across the country, also include:

- A Kickz football tournament, run by the Football Foundation, involving over 2,000 young people, with another 35,000 engaging in wider Kickz activity. These groups will include workshops involving conversations about the dangers of underage drinking

- Cinema advertisements showing the risks associated with drinking alcohol – part of the Government’s ‘Why let drink decide?’ campaign

- Local authority good practice guides facilitating work with the Police, Trading Standards, children’s and youth services to prevent the problems associated with underage drinking

- Additional funding of £350,000 for 69 Youth Crime Action Plan (YCAP) areas, for implementation of new police alcohol powers, including confiscating alcohol from young people and targeting retailers engaging in underage sales.

Home Office Minister, Alan Campbell, said:

‘Alcohol is often at the root of youth crime, so by reducing underage drinking we can stop young people being drawn into anti-social behaviour and crime.’

New powers to tackle teenage drinking come into force

New powers, introduced through the Policing and Crime Act, which received Royal Assent in November 2009, came into force for police forces across England and Wales at the end of January 2010.

The powers are:

- confiscating alcohol from young people – by amending police powers to confiscate alcohol so that they no longer need to prove that the individual ‘intended’ to consume the alcohol

- making it easier to move on groups of young people – by extending the police’s ability to issue ‘Directions to Leave’ so that they can be issued to people aged 10-15 and

- greater power to tackle persistent underage drinkers – by introducing a new offence for under-18s of persistently possessing alcohol in a public place.

- tackling those selling alcohol to children – by changing the offence of persistently selling alcohol to under 18s from three strikes within three months to two strikes in the same period

Also coming into effect were new powers for local councillors to tackle ‘problem’ licensed premises. In addition to the police and members of the public, local councillors will now also be able to call for a review to restrict or remove an alcohol retailer’s licence.

Schools Minister Vernon Coaker said:

“The powers coming in to force today support our work to delay the age at which young people start drinking alcohol. It is right that we give the police tough powers to crack down on the very small minority of young people who are causing problems in their communities.”

The new powers are part of a wider government strategy to tackle underage drinking and associated crime and disorder which was set out in the Youth Alcohol Action Plan, published in 2008.

The workplace: a forgotten area for alcohol studies?

By Jonathan Goodliffe, Solicitor

The workplace is not a primary focus of the government’s alcohol strategy for England and Wales. In one of its policy statements, Vernon Coaker, now Minister of State for schools, said that:

“Promoting a sensible drinking culture that reduces violence and improves health is a job for us all … Business and industry should reinforce responsible drinking messages at every opportunity.”

He was, however, mainly targeting his remarks at the drinks industry rather than at business in general. In a sense this is not surprising since it is the responsibility of business to resolve its problems, including those arising from alcohol misuse. However where businesses are able to deal with these problems within their own resources there may be significant savings to the public purse as well as benefits to the families of those concerned and society as a whole.

I took a six month postgraduate course last year at the Institute of Psychiatry. It was focused on alcohol and drug use in the workplace. The course director was Dr Kim Wolff, senior lecturer in the addictions. The course featured seminars led by a range of leading figures in the field and required us to complete several essays involving reviews of the scientific literature.

The focus was firmly on working environments where alcohol or drug misuse creates critical safety implications. These include the medical profession, the National Health Service, the US armed forces and the transport sector. They tend to be the working environments where proactive policies are developed and research is carried out. Problems from alcohol and drug use which arise within these environments are most tangible and are most likely, from a research point of view, to be within the comfort zone of professionals with clinical qualifications.

Yet the UK is primarily a service economy. Take the London financial sector, which is the largest in the world. It employs many highly paid people. In the 1990s there was a London code of conduct for principals and broking firms in the wholesale markets which said:

“Management should take all reasonable steps to educate themselves and their staff about possible signs and effects of the use of drugs and other abused substances. The judgement of any member of staff using such substances is likely to be impaired; dependence upon drugs etc makes them more likely to be vulnerable to outside inducement to conduct business not necessarily in the best interests of the firm or the market generally and could seriously diminish their ability to function satisfactorily.”

This regulatory guidance was abandoned in 2001 when the Financial Services Authority became the sector’s integrated regulator, probably because of the lack of any cost/benefit analysis supporting it. The 2004 Rowntree report on drug testing argued, controversially, that “There is a lack of evidence to suggest that drug and alcohol use is in fact having a serious and widespread effect on the workplace in modern Britain.”

Lack of evidence to support a proposition may suggest that it is unsound, but so little research has been published related to alcohol problems in the financial sector that no firm conclusions can surely be drawn either way.

One subject which clearly merits more consideration, is the extent to which heavy alcohol and drug use leads to inappropriate risk taking. There is research evidence that this may be the outcome in sexual activity and in the driving of motor vehicles. The same may perhaps be the case where, for instance, traders operate on the money markets or underwriters place large insurance risks. A recent enforcement action by the FSA against a trader for short selling involving amounts in excess of US$10 million noted:

“He drank alcohol over lunch and it appears that this affected his behaviour on his return to the off ce, although he was not visibly drunk. Between 17.04 and 19.37 on 6 February 2008, Mr X sold 24,868 lots and bought 19,493 lots of WTI Futures on the ICE web-based trading platform, WebICE. His trading represented over 30% of the total lots of WTI Futures traded on ICE on 6 February 2008. His short position reached 8,900 lots at 18.36. By 19.37, Mr X had a substantial net short position of 5,395 lots.”

Another possible subject for research is the extent to which heavy drinking by senior staff, who may often be role models, influences subordinates. The evidence indicates that senior staff are at least as likely to have drinking problems as their juniors. Yet an occupational health nurse recently told me that when she was interviewed for a job with a leading firm of solicitors it was made clear to her that health initiatives were to be targeted at secretaries and admin staff and that lawyers were above such matters. Workplace alcohol policies assume that line managers will need to take action against subordinates who have problems. The reverse may also be the case. Businesses that do have serious drug or alcohol problems at a senior level (such as those run by the late Robert Maxwell) are perhaps least likely to allow those problems to be investigated.

My own work within the IOP course indicated that some of the largest groups in the financial sector are content to leave the initiative on addressing alcohol problems to employment assistance programmes without developing their own alcohol policy. An EAP will often provide appropriate help for people who seek it, including evidence based solutions for problem drinking such as brief interventions and counselling. It may not, however, address the needs of those who do not seek help and are not encouraged by their colleagues to seek help. Nor will it usually provide for the more intensive treatment that may be required when people become alcohol dependent, which is in principle more likely to happen when their problems are not addressed at an earlier stage. The cost of treatment in the working environment can be met by private medical insurance when NHS provision is inadequate. Yet most PMI policies taken out by employers exclude cover for alcohol problems. This is not because insurance companies are unwilling to provide it to corporate customers, but because those customers are mostly unwilling to pay an extra 3% or so on the premium to secure the wider cover.

In commercial and financial environments researching business risks arising from alcohol and drug misuse requires a combination of professional disciplines. These include the ability to evaluate the benefit of addressing those risks as compared with other risks such as those arising from lack of skills, market forces and fraud. All of these risks may overlap to some extent.

A number of interesting papers on workplace alcohol policies were produced in the 1990s by, for instance, economist Melanie Powell. But interest in the topic seems to have waned since then and such research as has been published more recently usually focuses on safety critical workplaces and is often criticised for poor methodology.

Within the public sector the Boorman review recommends that, with a view to optimising patient care, “the NHS Operating Framework should clearly establish the requirement for staff health and well-being to be included in national and local governance frameworks to ensure proper board accountability for its implementation”. It is unlikely that this will ever be as significant a business priority (for “patient care” read “customer care”) in the private sector but it perhaps deserves to move a little up the list of priorities.

Book Review – Substance misuse: the implications of research, policy and practice

Edited by Joy Barlow, Reviewed by Dr Adrian Bonne

This edited book contains approximately two hundred pages of useful insights into the problems of tackling alcohol and drug abuse and dependency. The majority of the contributors either work or have strong links with problematic substance use in Scotland, the editor having been instrumental in establishing STRADA (Scottish Training on Drugs and Alcohol). This Scottish perspective is quite pertinent to a comparative view of attitudes, policies and treatment approaches across the UK. Other cultural dimensions are provided by researchers and policy experts from New Zealand and Italy.

The first part of the book provides a helpful summary of the development of alcohol and drug trends which provoke different government policies and responses. The commodity alcohol, “… has the most impact on the way we live, over the longest period, and which has caused the most damage, public concern and legislative responses…..” in contrast to drugs, the market of which is largely uncontrolled and “… is hidden and rarely disturbed by government or criminal justice agency intervention..” This review highlights the problems of managing alcohol problems in the community which is subjected to highly sophisticated marketing and lobbying activities of the drinks industry, which confounds the issues of control of a visible market by, until recently, undue influence of the industry on government policy. A useful comparison is made between the Welsh Assembly’s inclusion of alcohol and drugs in the same strategy, suggesting the common underlying motivation mechanisms for both alcohol and other drugs and includes service users in the planning of services; the “reintegration” approach to the rehabilitation of drug users as promoted by the UK government, with incentives linked to the welfare support; and the “recovery” perspective of the Scottish Government which seeks to bring about a change in culture and its main aim being to bring about drug-free lives. The debate concerning a “harm reduction“ approach as opposed to abstinence goals leans towards the latter in Scottish policy.

This introduction to the cultural and political backdrop to alcohol and drug issues lead to a consideration of the global price–related alcohol harm and overwhelming evidence of alcohol and poor health. The role of partnerships in responding to this set of socioeconomic circumstances is leading to modern regulatory systems as that emerging in New Zealand. Support for this community-development approach is provided by the example of the apparent success of smoking cessation in various regions.

The second section of the book focuses on treatment and recovery. Data from the DORIS (Drug Outcome Research in Scotland) study indicates that despite a significant use of engagement approaches such as needle and exchange schemes, more than fifty percent of DORIS respondents are still using heroin and fewer are in employment compared to those at the outset of their treatment. Furthermore, high levels of unsafe drinking continue and acquisitive crime continues to be a significant problem. One explanation for this is the under capacity of the substance misuse services to provide adequate intensive support for service users. The long term support needed to change someone into a non-drug user appears to be a very distant aspiration when such a large number of people are in need of support. The authors suggest the importance of differentiating between those who are likely to achieve abstinence and those for whom harm reduction is the most pragmatic way forward.

The importance of employment opportunities is highlighted but combining aspiration with reality is needed. The large number of barriers to employment result in many people failing to meet the demands of the world of work. A staged (re-) introduction is suggested as a way forward to prevent failure and negative motivational factors associated with relapse into dependency. A number of case studies are presented which illuminate the opportunities for developing this approach.

The final sections of the book focus on children affected by parental drug and alcohol misuse, the role of the family, prevention, and the impact of social exclusion. These sections are followed by a brief review of integrated working and workforce development.

In summary, the book provides a wide ranging commentary of the issues leading to substance misuse and society’s varying responses, which appear to be culturally influenced. It is easy to read and should prove useful for practitioners and those studying on social work and related courses. In view of the Scottish orientation of the contributors, and nutritionally associated alcoholic brain (ABD) damage which is at a high frequency in Scotland, it is surprising that no mention was made of Wernicke- Korsakoff syndrome (WKS). WKS is found in chronic alcohol abusers, and ABD at less apparent pre-clinical stages of cognitive dysfunction. ABD, even at sub-clinical levels, mitigates against the development of individual potential and life chances and impacts on personal relationships in the family and in employment. A section on nutritional dimensions of alcohol and drug misuse would add another often ignored aspect of these biopsychosocial problems.

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

Gambling industry harms and parallels with the alcohol world

Will Prochaska –

Coalition to End Gambling Ads