In this month’s alert

Dying for a drink – Alcohol related death rates almost double since 1991

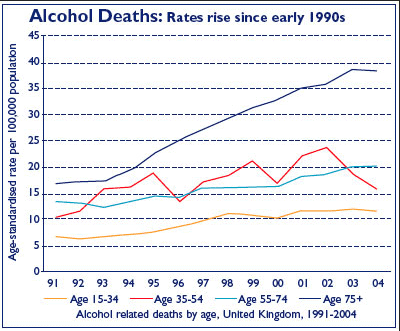

The alcohol-related death rate in the UK increased from 6.9 per 100,000 population in 1991 to 13.0 in 2004, according to data released by the Office for National Statistics. The number of alcohol-related deaths has more than doubled from 4,144 in 1991 to 8,380 in 2004.

The figures are an underestimate of the full amount of deaths as they only relate to deaths caused directly by alcohol. If indirect causes are taken into account the number of deaths could be 3 or 4 times higher. However, the new figures still show important and useful trends.

Speaking for the Royal College of Physicians, Professor Ian Gilmore, Chair of the College’s Alcohol Committee, said: “These new figures from the ONS are disturbing, but not surprising as they fit in closely with other recent figures such as hospital admissions for alcoholic liver disease and deaths from cirrhosis.

“The increase in deaths is likely to continue unless we can find some way to reverse the nation’s drinking habits. The College supports the Government’s Harm Reduction Strategy but if voluntary partnerships with industry and public education are not proving effective, the next step is direct intervention on issues such as availability of alcohol, price increases and restrictions on advertising.”

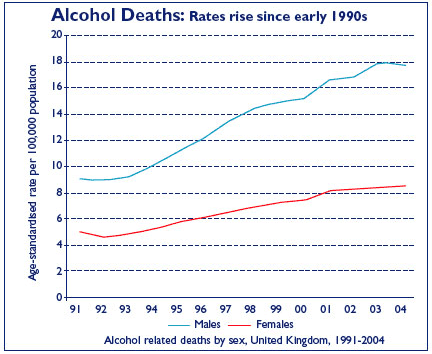

Death rates are much higher for males than females and the gap between the sexes has widened in recent years. In 2004 the male death rate, at 17.7 deaths per 100,000 population, was twice the rate for females (8.5 deaths per 100,000), and males accounted for over two thirds of the total number of deaths.

The figures

For men, the death rates in all age groups increased between 1991 and 2004. Men aged 35 to 54 had the highest death rate in each year. This rate more than doubled between 1991 and 2004, from 16.9 to 38.3 deaths per 100,000.

The death rates by age group for females were consistently lower than rates for males, however the trends showed a broadly similar pattern by age. The death rate for women aged 35 to 54 nearly doubled between 1991 and 2004, from 9.3 to 17.9 per 100,000 population, a larger increase than the rate for women in any other age group.

Rise in alcohol related hospital admissions to record levels

Drink-related hospital admissions in England have reached record levels according to a new compilation of statistics, published by The Information Centre for health and social care (The IC), which presents a broad national picture of alcohol use.1

Numbers admitted to hospital with a diagnosis of alcoholic liver disease have more than doubled over the past ten years with 35,400 admissions in 2004- 05, up from 14,400 in 1995-96. Twice as many men as women were admitted with this illness. Death rates linked to alcoholic liver disease have also risen steadily to just over 4,000 in 2004, a 37 per cent increase in the 5 years since 1999.

In-patient care for people who have mental health or behavioural disorders resulting from alcohol misuse, has also increased significantly, rising to126,300 admissions in 2004-05, from 72,500 in 1995-96 (75 per cent over the ten years).

Cases of hospital admissions of patients with alcoholic poisoning have also increased, 21,700 in 2004-05 compared with 13,600 a decade earlier. The report highlights that the nation’s thirst for drink begins at an early age. A national survey in 2005 found that nearly one in four secondary school children (22 per cent) aged between 11 and 15 said they had drunk alcohol in the week before they were interviewed. Cider, lager, beer and alcopops are the drinks of choice for this age group, with the average amount consumed doubling between 1990 and 2000 to 10.4 units per week. Consumption has remained at this level for the past five years.

A 2004 survey of adult drinking found that three quarters of the men interviewed (74 per cent) and over half of all women (59 per cent) had taken a drink in the previous week. Young adults were more likely to binge drink than any other age group; 33 per cent of men and 24 per cent of women aged from 16-24 drank more than double the recommended number of units (8 for men, 6 for women) on one day in the previous week. Older adults (45 to 64) are more likely to drink smaller amounts regularly, on five or more days of the week.

Although this research shows relatively high levels of alcohol consumption, the UK occupies a middle position when European Union countries are ranked according to average alcohol consumption. According to the World Health Organisation figures for 2001, Luxembourg heads the consumption table, with its residents drinking a per capita average of 17.54 litres of alcohol a year, compared with the UK’s 10.39 litres.

The survey also confirms that the weekend is the nation’s favourite time for drinking. Young people (16-25) and adults up to age44 drink most alcohol on Saturdays,33 per cent and 35 per cent respectively. Older people (64 plus) say they drink most on Sundays (30 per cent) and adults in middle age (45-64) consume the most alcohol on Saturday (24 per cent) and Sunday (26 per cent).

Professor Denise Lievesley, The Information Centre’s Chief Executive, commented: “This report presents a broad picture of drinking habits in England. It shows that we cannot underestimate the effect of alcohol on health. By presenting this data we hope that health professionals will be better equipped to put their work in context and to raise awareness of the dangers of alcohol misuse.”

1 Statistics on Alcohol 2006.

Alcohol and Health in Wales – A major public health issue

The rise in alcohol-related harm in Wales is documented in a new report “Alcohol and Health in Wales: a Major Public Health Issue”, published by the National Public Health Service for Wales. Based on published evidence, it details the health consequences of alcohol misuse in Wales.

Alcohol-related deaths have increased more than four-fold amongst Welsh men and more than three-fold among women in the last 20 years according to the report, which says that some 170 men and 90 women in Wales are likely to die of alcohol-related conditions this year.

As the real price of alcohol has fallen over the last 40 years, the amount consumed has doubled. Heavy drinking among teenagers in Wales is amongst the worst in Europe. Excessive drinking is causing a wide range of illness amongst people in Wales.

Cirrhosis of the liver is one of the major causes of death from alcohol misuse. Cancers,mental illness and accidents are others.

The report’s author, Dr Edward Coles, said, “‘Mediterranean-style’ drinking is no panacea. Comparison of different European countries shows that it is associated with high rates of cirrhosis. There is a tendency to think of crime and disorder as being the main cause of illness associated with excessive drinking. However, cirrhosis of the liver, cancer, mental illness, accidents, unwanted pregnancies and babies damaged by their mothers’ drinking are also important.

“Excessive alcohol use is a serious public health problem in Wales. Health would improve substantially if there was a reduction in the number of people who drink more than the guidelines.” Guidance indicates that men should drink less than 21 units a week and women should have less than 14 units.

Dr Coles said, “There are two mechanisms that have been shown to produce a substantial reduction in alcohol consumption – increased price and reduced availability. The National Public Health Service for Wales believe this is an important message for local licensing committees throughout Wales.” The report is available from the NPHS web site www.nphs.wales.nhs.uk

Police tell drinkers ‘wear nice pants’

Police have warned women intent on “getting ratted” to make sure they have waxed and are “wearing nice pants” in case they collapse.

The advice is contained in a free magazine launched by Suffolk Police which officers say is aimed at keeping women safe when they go out drinking and clubbing.

Safe! magazine also contains a picture of a girl in a mini skirt with the caption “if you’ve got it, don’t flaunt it” and it warns that alcohol can leave women looking like “wrinkly old prunes”. There are also mock horoscopes promising disasters of various kinds as a result of drinking binges.

Officers said they were adopting an editorial style which they hoped would appeal to women in their late teens.

A group which campaigns on women’s safety issues applauded the police’s efforts but said the style of the magazine was “bizarre”. Suffolk police explain that the publication forms part of their ‘Nightsafe” crime awareness and reduction campaign and it focuses on the three main ‘nightsafe’ messages:

- Don’t overdo it

- Friends stick together

- Get home safe

“There have been a number of attacks on women who have been drinking and there is a serious safety message to get across,” a police spokesman said.

“We’ve written this in a gossipy, tongue-in-cheek style in the hope that young women will pick it up and read it and take notice.”

“For those of you intent on getting ratted this weekend, think,” says the article. “If you fall over or pass out, remember your skirt or dress may ride up.

“You could show off more than you intended – for all our sakes, please make sure you’re wearing nice pants and that you’ve recently had a wax. “Better still, eat before you go out, think about how much you’re drinking, pace yourself and drink plenty of water in between bevvies or better still, don’t get in this sorry state – it’s not nice.”

A spokeswoman for the Suzy Lamplugh Trust said: “The language is bizarre. I’ve never seen anything like it before from the police. But they have a point. It’s no good simply telling young women not to drink. You have to get their attention. You have to applaud the police for trying.”

Readers’ survey

Alcohol Alert Magazine has been edited and published by the Institute of Alcohol Studies, in its present format, for over ten years.

The magazine aims to provide a broad range of information for all readers with a personal or professional interest in issues relating to alcohol. The magazine typically features discussions of alcohol research findings, analysis and evaluation of alcohol policy and legislation, insights and commentaries from experts in the alcohol field, and occasionally, book reviews.

We are currently carrying out a readers’ survey with a view to improving the magazine. We would like to know what the readers think of Alert’s current format and content. All information collected will be used to update the magazine and meet the needs of our readers.

We would be very grateful if you could take time to complete the questionnaire and email it to Emilie Rapley, Research and Public Affairs Officer.

We thank you in advance for taking part in our survey, and look forward to reading your comments and suggestions.

The Staff at the Institute of Alcohol Studies

Wouldn’t it be nice…

With the new Licensing Act 6 months into operation, John Tierney suggests that it is unlikely to achieve one of its main objectives.

The Department for Culture, Media and Sport has a dream: that the 2003 Licensing Act (which came into force in November 2005) will provide the basis for a transformation in the nature of the night-time economy in England and Wales. In the dream, town and city centres will no longer be dominated by concentrations of high-volume pubs, bars and clubs oriented primarily towards the business of encouraging young people to drink large amounts of alcohol. No longer will these ‘entertainment quarters’ be shunned by older (and some younger) people because of concerns about crime and disorderly behaviour, and a jaundiced view of the attractions on offer. In the dream, couples with children, the middle-aged and the elderly will cheerfully rub shoulders with young revellers as they too enjoy the delights of a night on the town.Some, as the fancy takes them,may drink alcohol, others may opt for a citron pressé or a milky latte, and the streets will bethronged with a mélange of well-behaved promenaders. Exactly how the 2003 Licensing Act will facilitate this transformation is, though, somewhat hazy.

None the less, it is a dream shared by many people, and the reference point is, of course, continental Europe. “We want to be more European”, said the then minister for Culture, Media and Sport, Richard Caborn, a couple of years ago, when arguing in favour of the new Licensing Act. At about the same time, a councillor from Greater Manchester – whose city centre night-time economy has been particularly successful (at least in economic terms) put it like this: “I spent time in Berlin over Christmas and was struck by the mixed age groups that used the city centre. Theirs is very much a café-and-cake culture, and we definitely see that as part of the Manchester vision.”

Also drawing on an image of continental café culture, the Department of Environment has, for over a decade, been arguing that the ‘animation’ and ‘crowding out’ resulting from a broader mix of participants will reduce problems of crime and disorder in town and city centres. What has not been considered is that an intermingling of different groups (including, for example, older people and children), within the context of an already established drinking culture, could lead to an increase in these problems.

Among central government and local authority policymakers striving to realise such a vision, ‘diversity’ has emerged as a key concept. It is acknowledged that making the night-time economy of England and Wales ‘more European’, will require achieving a diverse mix of participants enjoying a diverse range of leisure activities. Town and city centres during the evening, especially on Fridays and Saturdays, are often described as no-go areas for older people and couples with children. However, whilst it is not uncommon for local authorities to label these negative perceptions or concerns as exaggerated (a similar response occurs with respect to the ‘fear of crime’), the central issue is not the degree to which public perceptions correspond with ‘reality’; rather, it is the tolerance threshold associated with different publics. In other words, even if no criminal or serious disorderly behaviour was occurring, the fact that large numbers of inebriated young people are milling around engaging in (normal) boisterous behaviour is likely to act as a disincentive to participation. Community safety initiatives and effective policing (and the police have extra powers under the 2003 Act) can address such things as violent crime, criminal damage and urinating in the street, but they are more or less irrelevant when people are simply having a ‘good time’ and not harming anyone. For this reason alone, attracting current non-participants into town and city centres during the evening will continue to be a major challenge. If we look at the community safety initiatives that have been introduced around the country in recent years, it is clear that, where successful, they have generally made town and city centres safer for ‘typical’ participants in the night-time economy (welcome as that is), rather than acting as an incentive for current non-participants to join in.

Clearly, there also needs to be diversity in terms of what is on offer if these non-participants are to be enticed into the nighttime economy. Restaurants, theatres and cinemas, for instance, could make an important contribution, though as things stand, their impact will be linked to how near they are to heavy drinking areas within a town or city centre, particularly at the weekend. The fundamental stumbling block to the creation of diversity in terms of what is on offer, however, is the market and the way in which it is structured. High street businesses that are not based upon the consumption of alcohol have found it increasingly difficult to compete with those that are – witness the cinemas and retail outlets that have transmogrified into large capacity licensed premises over recent years.

As far as the future is concerned, unless they are remarkably philanthropic, entrepreneurs, in the shape of corporations or individuals, will only alter existing leisure attractions or develop new ones if it is judged to be commercially viable. There may, for example, be local people who would like to see a town centre club providing jazz, country music or late night cabaret, but how realistic is it to expect the development of these sorts of attractions, outside of major conurbations with large reservoirs of guaranteed customers? In terms of profitability, events of this nature cannot begin to compare with a one thousand capacity, themed vertical drinking bar.

Given the nature of the market, the power of the drinks industry, patterns of drinking in this country, and the powers available to Licensing Authorities, one would have to be immensely optimistic to believe that the 2003 Act constitutes the basis for the creation of diverse, multicultural, sophisticated and hassle-free leisure zones, at least in the foreseeable future. The reality is that the night-time economy, as it is presently constituted, is an economic sector dependent upon alcohol and, increasingly, one that caters for young customers who themselves are becoming dependent upon alcohol.

John Tierney is Lecturer in Criminology at the School of Applied Social Sciences, Durham University

Drinkaware Trust launched

Industry joins Government to promote ‘sensible drinking’ A new independent charitable Trust aimed at “positively changing the UK’s drinking culture and tackling alcohol-related harms” has been launched by Government Ministers Caroline Flint and Vernon Coaker, the alcohol industry and key stakeholders.

The ‘Drinkaware Trust’, voluntarily funded by the alcohol industry and to be up and running later this year, is described as a unique initiative born from the Government’s ‘Choosing Health’ White Paper and Alcohol Harm Reduction Strategy.

The new initiative is a further development of a Trust established in September 2002 as the charitable arm of the alcohol industry’s Portman Group, and originally known as The Portman Group Trust. In 2005 the Trust awarded a total of £100,000 to 55 projects around the UK.

The new Trust will bring together industry, charities, lobby groups, medical professionals and experts in the field to address ‘alcohol misuse’ and promote ‘sensible drinking’ across the UK.

Work by the Trust includes educational campaigns to promote ‘sensible drinking’ among the general public, project aid for local and national initiatives, and the running and evaluation of pilot programmes to tackle alcohol related harm.

Public Health Minister Caroline Flint said: “This is an international first. The new Drinkaware Trust is a model of how industry, stakeholders and Government can work together to achieve a shared goal. Alcohol misuse can blight the lives of communities across the country – not only harming the health of individuals but fuelling late night violence and causing a nuisance to society.

“The success of the Trust will depend on securing the support of a broad range of stakeholders across the UK – and that’s what we’ve done.

“There is nothing wrong with drinking in moderation. Alcohol is a normal part of society and we’re not trying to stop that. What we are saying is that people need to be sensible and not drink excess amounts that can lead to serious conditions such as liver cirrhosis or result in disorderly behaviour.

“Everyone has worked really hard to make this work and I am confident the new Drinkaware Trust will help in achieving this goal.”

The New Trust marks a significant milestone and underlines both the industry’s commitment to share responsibility for positively changing public behaviour, tackling and preventing alcohol misuse and the Government’s role to work in partnership with the industry and key stakeholders to achieve this.

It also forms part of the Prime Minister’s ‘small change, big difference’ initiative to draw together the power of businesses, the voluntary sector and local communities to tackle specific health problems by making it easier for people to change the way they live their lives.

Government has been working in partnership with the alcoholic drinks industry for some time to promote more sensible drinking. And the launch of the Drinkaware Trust marks another move in the right direction. Government is also working with the industry to implement their social responsibility standards, which will address irresponsible promotions, underage sales and includes putting sensible drinking messages on alcoholic drinks labels.

Vernon Coaker, Home Office Minister, said: “The Home Office has put in place tough measures to deal with alcohol related disorder. I have made it clear that we will not tolerate the minority of people who drink to excess and cause fear and intimidation in our towns and cities.in the UK. The Trust has set itself challenging goals. By working together, the drinks industry and organisations tackling alcohol harm will make these all the more achievable.”

Chris Searle, Chairman of The Portman Group, said: “We are delighted that we have been able to provide the practical means to take the implementation of the alcohol harm reduction strategy forward on the education and campaigning front. This approach demonstrates the benefits of the industry, government and other stakeholders working in partnership around a shared agenda.”

An interim chief executive will be appointed very shortly and the Drinkaware Trust will be seeking a chair, a permanent chief executive and 13 independent trustees to run it. Trustees will come from a broad base including alcohol experts from the health, education and voluntary sectors as well as the drinks industry. There will also be two lay trustees. Once they are appointed, it is the aim that the Trust will be fully operational by the end of the year.

The alcohol industry has pledged £12 million to the charity over the next three years to fund the Trust’s activities, including promoting the charity’s consumer information website www.drinkaware.co.uk in advertising, at point of sale and on product labels.

The new Trust also has the support of the Scottish Executive, the Welsh Assembly and the Northern Ireland Office who have all signed the Memorandum.

NHS ‘hypocrites’ invest in Diageo

The controversy about whether it is right or sensible for public health bodies to form partnerships with the alcohol industry took a particular turn in Scotland when NHS chiefs were branded “irresponsible hypocrites” for investing charitable donations totalling £250,000 in Diageo, the world’s leading premium drinks business, owning such brands as Smirnoff vodka, Guinness, Gordon’s , Bailey’s and Johnnie Walker whisky.

Brian Adam, the SNP MSP for Aberdeen North, said: “It’s inappropriate and irresponsible for the health service to be bolstering the drinks industry. Having shares in a company like Diageo is hypocritical. There are plenty of other areas which can guarantee a reasonable financial return without damaging society’s health.”

NHS Grampian has an endowment fund which consists of money donated to the trust and left in wills. Cash from it has allowed the trust to buy almost £30 million worth of shares in a host of firms, including Shell and Vodafone.

News of the investment in Diageo coincided with reports of a 65 per cent rise in alcoholrelated liver disease in Grampian during the past five years. The Scottish Executive is trying to curb the binge-drinking culture as hospitals struggle to cope.

Alayne Jones, of the Alcohol Advisory and Counselling Service in Aberdeen, also criticised the Diageo investment. “It is hypocritical. But the problem can only be sorted by the government and Scottish Executive,” she said. “When they stop raking in huge profits from alcohol firms then other organisations might follow suit.”

NHS Grampian said the companies invested in by the endowment fund were carefully selected. “We don’t see the investment as a conflict of interests,” a spokeswoman said. “We have financial advisers who tell us where to invest the money. But we will not invest in arms companies or tobacco firms. But no-one has said that drinking responsibly is bad for you. However, these investments are reviewed all the time so in the future we may think differently about having money in Diageo.”

Tom Wood, who chairs the Scottish Association of Alcohol and Drug Action teams, defended the investment decision. “We’re not anti-alcohol per se,” he said. “We have got no issue with Diageo or other drinks companies, although I might sometimes be critical of the way they promote their drinks.”

Evidence base for EU strategy released

‘Alcohol in Europe: a public health perspective’ sets out our habits, harms and hopes over 400 pages, but how much will be included in the strategy?

By Ben Baumberg, co-author of the report and Policy and Research Officer at the Institute of Alcohol Studies

Five years ago, the leaders of the countries that then made up the EU signed a resolution on alcohol and young people, setting in train a process that will ultimately give us the first EU strategy on alcohol. We are not there yet – the strategy itself is due out this autumn – but May 2006 saw at least one staging post along the way, with the release of the evidence base on which the strategy will be based. Entitled ‘Alcohol in Europe: a public health perspective’, the report spells out the effects of alcohol in the 25 countries of Europe, and what we can do to change these effects.

While the report has 10 (lengthy) chapters within its 400-plus pages, there are two main themes running through it which have crucial importance for the EU’s strategy – (1) what alcohol in Europe looks like now, and (2) how we can make it look better in the years to come.

Where we are now

While alcoholic drinks have been around for millennia, alcohol was only rarely seen as a social problem before medieval Europe. Aside from more recent medical developments showing the health consequences of drinking, the biggest change was a series of associated parts of ‘modernization’ – industrialization, improved communication links – combined with the spread of knowledge about how to distil alcohol into stronger spirits. The increase in drinking and drunkenness these allowed was met by large ‘temperance’ movements across much of Europe in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, campaigning against the ‘evils of spirits’ before sometimes moving on to an opposition to all alcoholic drinks.

While these temperance movements have today faded to insignificance in most (but not all) EU countries, the modern era of strong, available alcohol is still with us. The EU is the heaviest drinking region in the world, drinking 11 litres of pure alcohol per adult per year, although a minority of 55 million adults (15%) do abstain. An estimated 23 million Europeans are dependent on alcohol (5% men, 1% women), while 100 million (1 in 3) are estimated to ‘binge-drink’1 at least monthly in the 15 ‘old’ EU countries alone, and 1 in 6 adolescents aged 15-16 bingedrink1 at least three-times per month. Drinking levels and patterns differ between different groups within the EU population, with lower socioeconomic groups and particularly men more likely to be drunk or be dependent on alcohol.

While changes in recent years are not as dramatic as those of medieval times, the picture is still noticeably different in 2006 from what it was in 1966 – or even in 1996. The ‘spirits drinking’ countries of northern Europe now drink more beer than spirits, while the high consuming ‘wine-drinking’ countries of southern Europe drink much less wine and indeed, much less overall than they used to. While there is still a clear north-to-south gradient in some aspects of drinking behaviour (such as frequency of drinking), the differences are much less than many still believe; Greece, for example, drinks more of its alcohol in spirits than Norway, while recent data also suggests that Spaniards drink more beer than wine. Adolescents and young adults have moved even faster, with the cliché of French and British drinking belied by UK young adults drinking more often with meals than their French counterparts.

The down sides of this level of drinking are there for all of us to see. The crime caused by alcohol leads to 33 billion Euros worth of costs – partly in police time, but also in criminal damage and needless security guards – while 17bn Euros is spent on alcohol-caused health care across the EU, and 60bn Euros worth of potential economic contributions are lost. This is aside from the lowered quality of life for addicts, and the associated pain and suffering of family members (which itself can be valued at 68bn Euros), let alone the pain and suffering of the victims of alcohol attributable crime (valued at 9- 37bn Euros).

Most importantly of all, alcohol is responsible for 195,000 deaths each year. However, this also takes us into the tricky territory of the epidemiology of old age, given the 160,000 deaths delayed, which can be easily misinterpreted: It does not make sense to say that “the full toll of alcohol is 40,000 deaths,” by setting the deaths delayed against the deaths caused. Most of the deaths delayed occur in a different age group (the very old) from most of the deaths caused (youth and middle-age), and for different types of drinkers (frequent light drinkers rather than heavy and binge-drinkers).

The number of deaths delayed is very likely to be an over-estimate, given three substantial errors in the current estimates. Firstly, the epidemiological studies on alcohol often bundle former drinkers in with consistent abstainers, as Kaye Fillmore has recently shown. Secondly, the studies forget that people’s drinking changes over time – a recent British Regional Heart Study paper shows that this error was the difference between drinkers having a lower risk of death than abstainers with the error vs. a higher risk when it was taken out. Finally, heart disease deaths at older ages are highly over-estimated, with many coroners using ‘heart disease’ as a code for both uncertainty or general organ failures.

It is probably more sensible, then, to focus on the more accurate estimate of 115,000 deaths caused up to the age of 70, and the more robust estimate that alcohol is the third most important cause of premature death and disability in the EU – ahead of factors such as illegal drugs, obesity/overweight and lack of fresh fruit and vegetables.

The EU’s political engagement with alcohol has been focused on young people, and it is they that are the group that is most at risk. Alcohol isthe single biggest cause of premature death in young adults – responsible for 1 in 10 premature female deaths at this age, and an appaling 1 in 4 male deaths. What is more, the trend in slightly younger adolescents since the mid-1990s has been for increased binge-drinking,and while this has stabilised more recently, this suggests that the future toll is even greater than the current one.

Alcohol is not a simple substance, and we must get used to its nuances and complexities –causing deaths while saving lives, inflicting pain while producing pleasure. Yet the overwhelming image from a health perspective is the damage that alcohol causes in the EU, touching on nearly every aspect of human life. The complexities, and the need for action, raise challenges as to the best future action on alcohol in Europe, which takes us into the rest of the report.

Reducing harm in Europe

At its simplest, there are three things that we need to know before deciding on a European alcohol strategy. The first is what the law allows us to do. The second is which policies work in reducing harm. And for each policy that works, the third is considering the costs of that policy compared to its benefits.While the second area is the one most people think of when they hear the siren call of ‘evidence based policy’, the policy debate can benefit from the research contribution in all three areas.

An interest in international law is not what makes most people passionate about alcohol and addiction issues. It only becomes important when it stops health policy makers adopting effective policies – which it does, but not as often as is sometimes insinuated. The world trade law of the WTO sets certain conditions for health policies, for example, but the WTO have also demonstrated that they will prioritise health over trade when these conditions are met. Similarly, the European Court of Justice has upheld trade-distorting alcohol advertising restrictions, because “it is in fact undeniable that advertising acts as an encouragement to consumption” (in their words) and that Member States can decide on how much they want to protect human health.

More importantly, the treaties signed by nationally elected leaders – which make up ‘EU law’ – do not give the EU the powers to make policies for health unless they are a by product of creating an efficient EU market. While this means that an EU strategy can only ever encourage certain policies (such as sensible licensing restrictions), there are other areas where EU legislation can help the smooth runnings of the market, such as for drinks health warnings or advertising.

While not the only essential information, reviewing what works in reducing alcoholrelated harm is perhaps the most important basis for action –otherwise all our goodwill and efforts will be wasted. This is sensitive, however, as finding that a policy ‘does not work’ suggests that those of us working in that area have been wasting our time…which is why we must be clear that school-based education is neither an effective single policy nor a futile effort. Reviews of educational programmes show that the overall effect is either small or zero – but given that education on alcohol is both a human right and potentially lays the ground for other interventions, we have no excuse for not trying to make that small effect as large as possible (see page 257 of the report for a guide to improving alcohol education).

Other policies that generally work well include unrestricted breat testing, lowered blood alcohol concentration levels for drivers (and even lower ones for young drivers), regulating the market (e.g. licences, taxes) and brief advice to heavy drinkers (e.g. by GPs). Policies that generally don’t work well include designated driver campaigns and advertising self regulation. Some policies have research suggesting that they will have some effect, even if the evidence isn’t conclusive – such as for advertising restrictions. And finally, we must remember that policies are not ‘magic buttons’ to be pressed and forgotten about… their effectiveness depends on what happens around them – mass media campaigns work well if they support specific interventions, for example, while raising the minimum age for buying alcohol will not work if it is not properly enforced.

No researcher should fool themself that policy makers will simply adopt the most effective policies – and nor should they, given the number of considerations that matter for making and implementing any policy in a democracy. But each of these other considerations can be better understood from the research, including the economic costs of public health policies. Alcohol is clearly an important economic commodity, with the EU playing a central role in the global alcohol market, and several hundred thousand jobs linked to it at the very least. However, most discussions of this miss an obvious point – if people spend less money on alcohol, they have more money to spend on other goods. This means that for every job lost producing or selling alcohol – and the evidence suggests the link with consumption levels may not be as strong as might be thought – others will be generated elsewhere in the economy. More sophisticated modelling in the tobacco field suggests that public health policies could even lead to an increased number of jobs, depending on exactly how people spend the money they save from less alcohol. In otherwords, public health policies on alcohol are unlikely to have any significant impact on the European economy – and may even slightly help it, given the reduction in the considerable social costs of alcohol.

So what happens now?

Put in the starkest possible terms, the report shows that alcohol is a major public health problem, but that we know what to do to reduce this level of harm. This in itself is unlikely to be surprising to most readers of Alcohol Alert; but for the process of making policy in the EU it is a crucial basis from which to proceed. What is now left to do is the messy business of policy debate – which is less a matter of evidence than one of argument, persuasion and passion. We are now at a stage rich in potential; what remains to be seen is whether we look back at this moment with regret at how much difference we failed to make, or whether we look back with pride that the first EU strategy on alcohol genuinely changed Europe for the better.

Reference

1 Defined as 5+ ‘standard drinks’ on a single occasion. The problems of defining binge-drinking are discussed further in chapters 1 and 4 of the report.

‘Beer crazy’ World Cup

Before the start of the World Cup in June, there was widespread anxiety that the tournament could risk resulting in a ‘binge drinking own goal’. Previous football events such as Euro 1996, and the 1998 World Cup, saw many episodes of violence and rioting, as a result of mass confrontations of inebriated fans, and it was feared that a possible upsurge in alcohol related crime and disorder was likely to occur as a result of the 2006 World Cup, especially as the timing of the matches coincided with usual drinking hours – contrary to the previous World Cup held in Japan in 2002.

The timing of the tournament was thus seen as potentially problematic. On the six month anniversary of the implementation of the legislation, shadow secretary of state for Culture, Media and Sport, Hugo Swire said: “It is too early to judge the full impact of the of the extended opening hours, but the summer, and particularly the World Cup, will be the real test of what effect the changes will have”

How big a test of the new licensing regime and its longer trading hours the World Cup would provide was, however, unclear, as the matches were all scheduled to be played at times when the pubs would have been open in any case under the old regime.

Impact of Licensing Act 2003

Independently of the World Cup, the impact of the new Licensing Act is uncertain. For one thing, the effects of the nationwide police enforcement campaigns coinciding with the introduction of the Act have complicated the picture. This has not prevented the Government and the licensed trade from claiming that early crime figures show the new Act is succeeding as there does not appear to have been the upsurge in crime that some in the media predicted.

One body clearly unconvinced by the Government’s presentation of the crime figures was the Association of Chief Police Officers. Chris Allison, ACPO lead on Licensing and Commander in the Metropolitan Police Service, said: “ACPO has consistently welcomed much of the new Licensing Act and the Police Service is already making use of the new powers that are available to it. We fully agree with the Minister that is far too early to say whether the extension to the licensing hours has had a positive or negative impact on crime and disorder.”

The figures quoted are not comparing like with like and do not take account of the fact that the Home Office gave £2.5 million in additional funding for Police and Local Authority enforcement activity during the period 14th November 2005 through to the 24th December 2006. ACPO has consistently said that it will be at least a year before we can measure the true impact of the act and we remain firmly of that view.

ACPO is working closely with the Government and other key partners on the review of the Guidance in an attempt to deal with areas of concern that have become apparent since implementation of the Act.

Beer Bonanza

With an estimated 815 million pints of beer sold during the World Cup, which represents an increase in sales of 60 million pints compared with the same period last year, the licensed trade have unquestionably come out as the true winners of the tournament. The British Beer and Pub Association (BBPA) reported that “the feel good factor as well as convenient kick off times helped many pubs boost sales and attract a large clientele”. Before the start of the event, the British Retail Consortium predicted that for every week England remained in the tournament, an extra £124 million would be spent on food and drink, a figure mostly comprising beer, but also wines and spirits, snacks and confectionery. Evidently, opportunities to maximise profits during this time were welcomed by retailers beyond the licensed trade, and sales of football paraphernalia – ranging from inflatable hands to large screen televisions – soared.

Benefits for the alcohol beverage industry have spanned beyond the UK, however, as Anheuser-Busch, the brewer of Budweiser, and official sponsor of the 2006 FIFA World Cup, has just announced that it will retain its sponsor position until 2014. A spokesperson for the brand claimed: “In every corner of the World, football fans share a passion for their favourite teams and players, and they enjoy watching the games with a cold beer”.

This recent announcement has merely sparked up the heated debate surrounding the sponsorship of sports events by alcoholic brands, a marketing strategy believed to be particularly effective amongst young people. The US based Centre for Science in the Public Interest has circulated a “Global Resolution to End Alcohol Promotion in World Cup Events”, seeking the endorsement of concerned organisations and government officials.

It is hoped that this will represent a first step towards diminishing the influence of the alcohol beverage industry, whose interests, certainly in the UK, continue to be, to a large extent, protected by the Government. Indeed, this ambiguous ‘entente’ has been well documented by the Institute of Alcohol Studies and others and the implementation of the Licensing Act 2003 merely served to reinforce the drinks industry’s position as the key stakeholder.

Before the World Cup, the BBPA consented to an ‘action plan’ with Government Ministers, in an effort to encourage corporate social responsibility. The proposed aim of this was to “target sales to under 18s, continue to improve drinks retailing standards and deliver responsible trading practices over the World Cupand summer period” (BBPA Press Release 16 May 2006). However, this pledge appears to be at odds with a comment made by a BBPA spokesman, who claimed: “ If we make it to the final the whole country will go beer crazy in celebration” (The Publican 8 June 2006). He also suggested further measures would be implemented within licensed premises in order to create a safe environment for the fans, including ‘enhanced security on the doors where needed, entertainment after the matches so people don’t all leave at once, calming music played, and food promotions to make sure customers are eating as well as drinking’.

In the aftermath of the tournament, Mark Hastings from BBPA applauded licensees for the successful management of the event: “Pubs once again proved they are the home of responsible drinking and the ideal place to experience the roller coaster ride that is the inevitable part of following England in the World Cup”.

The national team’s opening match against Paraguay could perhaps be best described as such, given the violent fights that broke out during the match, resulting in outdoor television screens being banned in London and Liverpool. Although no exact figures of arrests for alcohol related offences during this period have been released in the UK, a recent poll conducted in five European countries suggests that England is widely considered as having the worst behaved and most troublesome fans,predominantly as a result of excessive alcohol consumption. However, it was also reported that of the 9000 fans arrested in Germany, 810 cases involved England fans, most of which were in fact ‘preventive arrests’; the cooperation between police forces in Germany has been highly praised, and the British Police successfully managed to keep at bay the 3500 known hooligans prevented from entering the country.

Nonetheless, the impact of the tournament in terms of alcohol related crime and disorder still remains unclear, as the results of the 4th Alcohol Misuse Enforcement Campaign (AMEC), which ran one month prior to the event are still unknown. Indeed, the £2.5 million nationwide campaign,launched by the Government and the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO), involved all 43 police forces in England and Wales, and was expected to set standards of ‘acceptable behaviour’ across British town and city centres. The campaign was the second to run since the implementation of the Licensing Act 2003, in November 2005; the legislation granted the police additional powers of enforcement to combat alcohol related crime and disorder, by enabling them to take firm action against shops, stores, pubs and clubs selling alcohol to under 18’s, as well as bars and clubs that actively promote excessive drinking. Despite these additional powers of enforcement, it is unlikely that the majority of licensed premises will have been suddenly transformed into safe havens of relaxed entertainment.

Information or data concerning local police enforcement initiatives remain dispersed and largely anecdotal. Recently published Home Office Statistics from the 2006 Crime Survey for England and Wales, allegedly show that there has been ‘no indication of a rise in the overall level of offence or a shift in the timing of offences as a result in the changes in opening hours of licensed premises’. These figures have already been embraced by the recently appointed Licensing Minister, Shaun Woodward, who echoed this view by claiming that the new regime had led to ‘no discernable increase in alcohol related crime and disorder since November’. It is yet too early to draw conclusions on the impact of the World Cup during this transitional period; as expressed before, the effects of the legislation are likely to be cumulative, and any objective evaluation should account for the exceptional circumstances that are the combination of major police enforcement campaigns alongside an international football tournament.

Emilie Rapley

Policy and Research Officer

at the Institute of Alcohol Studies

Discriminating against the former drinker

By Jonathan Goodliffe

Does this kind of discrimination exist?

People who have a history of problem drinking usually will not want to tell prospective employers about it. If they still have the problem they may want to cover it up. If they have a reasonable record of sobriety they may also want to cover it up in case they might be the victim of ignorant prejudice. There is no legal duty to make an unsolicited disclosure of these matters, although it is sometimes best to do so.

Some professions, such as the law and medicine, have had special difficulties facing up to problem drinking among their membership. On the one hand people may be reluctant to take effective action to help a colleague when his drinking is causing serious problems. On the other hand, after he has had appropriate treatment and got sober he may find it difficult to re-establish his career because of the profession’s reluctance to trust him with a responsible job. It may, of course, be justified. It takes time to rebuild professional confidence and competence after long term addiction.

Medical screening

Nowadays an employer may ask a prospective employee to complete a questionnaire to establish whether he is medically fit to carry out his job. If it discloses problematic conditions a medical report may be asked for. Sometimes the applicant will be referred straight to a doctor or organisation providing a screening service.

Any information provided by the candidate in answer to the questionnaire and the contents of the doctor’s report will usually qualify as “sensitive personal data” under the Data Protection Act 1998 and must be “fairly processed”. Practical guidance as to how employers should handle this data is given on the web site of the Information Commissioner.

Medical screening can, however, sometimes be unpleasant, intrusive and disproportionate. The questionnaire may require the applicant to give information concerning medical conditions for the whole of his life time, making compliance particularly onerous for people in the later stages of their careers. The applicant may also be asked questions about the health history of his family, whether living or dead. Sometimes a medical screening may last several hours and amount to a full medical examination. It is questionable whether practices such as these amount to the fair and lawful processing of sensitive personal data as required by the 1998 Act. They may also affect the usefulness of test results for specific functions such as blood pressure.

The medical approach

Bissell & Haberman commented (‘Alcoholism in the Professions’ (1984)) that “alcoholism is the most common, serious illness likely to affect a professional in the first fifteen years after completing graduate education”. Yet aspiring doctors receive very little training on the health effects of alcohol (in contrast to, for instance, more respectable common conditions such as hypertension and depression). They may acquire the necessary know-how as they go along in their careers, but often they do not.

The 1998 Act defines “processing of data” as including “retrieval, consultation or use of the information or data”. Arguably only someone with appropriate qualifications and training can “fairly process” medical data in order to express an informed view on whether the applicant’s past drinking is likely to cause problems in the future. A qualification as a general medical practitioner on its own may be insufficient. Some prospective employers will make an initial review of the answers to the questionnaire and then, if a problematical medical condition is revealed, refer to an appropriate specialist. This seems the most sensible practice.

A right not to be discriminated against?

Once the prospective employer has received the medical report and complied with its duties under the 1998 Act, there is nothing in law preventing it from discriminating against people with a record of addiction, whether or not they are still drinking or using. So in theory the employer can apply the concept of alcoholism as an incurable disease to its logical conclusion by refusing to employ someone who has, for instance, been clean and sober for 5 years.

This contrasts with the position under the Americans with Disabilities Act, where addiction counts as a disability. The US Supreme Court has, however, construed the duty not to discriminate narrowly. In Raytheon v Hernandez (2003) an employee had a drug test at work, tested positive for cocaine and was dismissed. He subsequently got successful treatment for his alcohol and drug addiction, and applied to be re-employed. The Court held that the employer was entitled to turn him down in reliance on its policy of not reemploying staff who had been guilty of workplace misconduct.

In the UK where the prospective employee’s health record includes, for instance, a history of depression as well as addiction (the two conditions are often co-morbid) the depression may count as a “disability” and trigger rights under the Disability Discrimination Act 1995. The Employment Appeal Tribunal has ruled that this applies even where the depression is caused by the drinking or drug taking.

Article 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights requires that “the law shall prohibit any discrimination and guarantee to all persons equal and effective protection against discrimination on any ground such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status”. “Other status” might include a record of medical conditions. International instruments such as the Covenant, which do not have direct legal effect, may nonetheless influence the development of domestic law.

Discrimination on the ground of the applicant’s opinions

A sub-species of discrimination is sometimes applied against professionals in the addictions field. Within that field widely differing opinions on the cause and nature of alcohol and drug problems are held. Many people who have had addiction problems regard themselves as still suffering from an incurable illness years after they have become clean and sober.

The disease concept of alcoholism is, however, a minority view in the field of the addictions, particularly in the UK. So if, for instance, a “recovering alcoholic” applies for a job with an organisation which follows alternative theories, his belief as to the nature of his condition may be regarded as inconsistent with the approach to treatment adopted by that organisation. Alternatively his approach may be regarded as too strongly influenced by his personal experience and thus lacking in scientific rigour.

Sometimes this may operate in reverse, when someone who does not believe in the disease concept applies for a job in a treatment centre applying the “Minnesota Model” of treatment, which endorses that disease concept. He too may be rejected on the grounds of his beliefs.

If a person applying for a job in the field of addictions is doctrinaire in his beliefs and entirely rejects the value of alternative theories and approaches, he may well be unsuitable. Sometimes, on the other hand, it is the employer’s attitude which is problematical and doctrinaire. But is there anything necessarily inconsistent, for instance, between a belief in the disease concept of alcoholism and a recognition of the value of behavioural therapies? Theories of addiction, moreover, have much common ground as well as areas of disagreement.

Discrimination in this form may, when carried out by a“core” public authority, such as an NHS trust or a local authority, contravene the Human Rights Act 1998. Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, to which the 1998 gives limited effect, provides: “Everyone has the right to freedom of expression.This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority”.

After employment has begun

When the employee has been taken on with knowledge of his medical record further issues arise. Should the data remain within the personnel department or should it be communicated to the employee’s line manager? In most cases the line manager will not need to know, but in some cases it may be desirable and appropriate that he should. The fair processing of this data will, however, surely require that the employee should be consulted at every stage where the data is communicated or used in any way, so that only those who need to know get to know and the data is not used unfairly behind the employee’s back.

If the line manager does get to know of the employee’s health record then any subsequent use of it will amount to “processing”. The 1998 Act requires that the processing must be fair. If, for instance, the data influences decisions as to whether the employee should be promoted, given additional or different responsibilities, or made redundant, the employee must generally be consulted. Moreover the data protection principles require that data should be kept up to date, sousing the outcome of a pre-employment screening several years after the employment has started is likely to be problematical.

Information about a person’s drinking history and the application of the label “alcoholic” to him is sensitive for a number of reasons. First, the label is often particularly damaging in career terms. Secondly, many people are uncomfortable discussing the subject. If they have a concern about an employee’s drinking past this may influence their decision-making without their being able or willing to articulate those concerns to the employee. Thirdly, because the opportunities for discussing this “unmentionable” subject are limited, mistakes and snap judgments are more likely to be arrived at than in relation to other management issues and medical conditions.

At the same time there is a danger of the employee himself imagining discrimination and unfair treatment when the reality may be otherwise. Indeed his own depressive tendencies may suggest that he is being treated unfairly when that is not the case. On other occasions his concerns may have a real foundation but be difficult to prove. They may provoke denial and righteous indignation if raised with the employer.

Data not caught by the 1998 Act

Sometimes, of course, the employer’s knowledge of the applicant’s problematic drinking derives not from the medical screening but from being tipped off over the telephone when taking up references or otherwise by word of mouth (particularly within close-knit professions or specialities). Another possibility may be that the applicant himself makes a full disclosure informally at interview. The disclosure may not be recorded in writing but will be remembered by those to whom it is made.

A recent decision by the Court of Appeal suggests that data in this form may not be caught by the 1998 Act and thus may not be subject to the fair processing requirement, unless, perhaps, it is used in conjunction with data which is caught by the Act.

Enforcement

Damages or compensation can be claimed for breaches of rights under the Human Rights Act 1998, the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 and the Data Protection Act 1998. So, for instance, a job applicant might be subjected to a poorly conducted medical screening involving unfair processing of his sensitive personal data. It might result in his being refused the job on medical grounds. In that event he might be in a position to claim substantial compensation against the employer under section 13(1) of the 1998 Act. It would be a defence, however, to show that even if the screening had been properly conducted the result would have been the same. And if he is offered the job and his only damage, therefore, is the distress arising from the handling of the screening he cannot sue (section 13(2)).

Suppose he starts the job and years later does not get a promotion because of concerns about his addiction record. Those concerns are not addressed in conformity with the 1998 Act. If he can prove this he should recover substantial compensation.

He may also want, at that point, to walk out of the job. Can he say that the same behaviour resulting in the contravention of the 1998 Act also amounts to a sufficient breach of his employment contract as to justify him treating the contract of employment as at an end and claiming damages for unfair dismissal? This proposition does not yet seem to have arisen in the courts. If it does arise the outcome is likely to depend at least partly on the wording of his contract.

Jonathan Goodliffe is a solicitor who writes from time to time on alcohol and the law. A fuller version of this article is available on his web site at www.articles.jgoodliffe.co.uk/ articles/discr.htm

Discrimination against people with alcohol problems

Evidence that people with alcohol dependence often face discrimination from individuals and institutions was found by a German survey of public attitudes. It appeared that public attitudes and beliefs about alcohol dependence are more negative than those about diseases such as schizophrenia, depression, Alzheimer’s disease, rheumatism, diabetes, AIDS, myocardial infarction, and cancer. These attitudes affected public preferences for resource allocation.

In the survey:

- Most (85%) thought alcohol dependence, more than any of the other diseases, was self-inflicted.

- More respondents (78%) said they would ‘distance’ themselves from people with alcohol dependence more than from people with other diseases.

- A little over half believed that alcohol dependence was severe, but only 30% felt it could be treated effectively.

- Just 4% thought they personally were at risk for alcohol dependence.

- Only 7% of respondents said they would spare alcohol treatment from budget cuts if resources were scarce.

Reference:

Schomerus G, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC. Alcoholism: illness beliefs and resource allocation preferences of the public. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;82(3):204–210

Leading charities call for urgent Government action for UK’s 1.3million children affected by parental alcohol problems

A coalition of eleven prominent charities and academics led by Turning Point has called for urgent action to address the misery faced by one in eleven children in the UK who live with parents with alcohol problems. Turning Point’s ‘Bottling it Up’ campaign, launched earlier this year, found that 1.3m children in the UK are affected by parental alcohol problems.

In a letter which was delivered to the Children’s minister, Beverley Hughes MP, the coalition called on the Government to launch a national inquiry to examine the impact of parental alcohol problems and to develop new services for children and parents and start rebuilding the lives of those affected.

The letter was signed by Turning Point, Adfam, Alcohol Concern, Children’s Society, Barnardos, NACOA (National Association for Children of Alcoholics), Bath University, Brunel University, Stella Project, Princess Royal Trust for Carers and Drugscope.

Turning Point’s ‘Bottling it Up’ report, which was published in May 2006, reveals the devastating impact of alcohol on children and their families:

- Children suffer from behavioural, emotional and school-related problems. They worry about the harm to their parent’s health, find it difficult to make friends and often have to take on the burden of looking after siblings, parents and the home. They are also more likely to express anger through anti-social behaviour and develop alcohol problems themselves.

- Parents who misuse alcohol struggle to show their children enough affection and care. They can be emotionally distant from them and caring responsibilities may be left unattended.

- Overall, the whole of family life is disrupted and chaotic, they become isolated from other family members and the community and conflict and violence are more common.

Turning Point’s Chief Executive, Lord Victor Adebowale, said:

“The Government cannot ignore the children and families affected by alcohol misuse any longer. We are dealing with a major social and public health challenge which devastates hundreds of thousands of lives. The strength of support from other leading organisations and from the general public is giving the profile of this issue a great boost. We hope to see imminent commitment from the Government to assess the scale of the impact of parental alcohol misuse and begin to work with agencies to find new ways to support families.”

A theology of the use and misuse of alcohol

Debates about measures to tackle alcohol problems usually touch sooner or later on questions of rights and responsibilities. Are people who get drunk exercising their legitimate rights or behaving irresponsibly? What of those who become dependent on alcohol? Can they be held to account for what they do, or do not do, while they are under the influence?

Here Professor Christopher Cook introduces the themes explored in his new book ‘Alcohol, Addiction & Christian Ethics’. Professor Cook, as well as being a psychiatrist with a special interest in alcohol problems and a scientific advisor to the Institute of Alcohol Studies, is also an ordained minister of the Church of England.

“Do you not know that wrongdoers will not inherit the kingdom of God? Do not be deceived! Fornicators, idolaters, adulterers, male prostitutes, sodomites, thieves, the greedy, drunkards, revellers, robbers— none of these will inherit the kingdom of God.”1

St Paul seemed pretty clear that some things were simply wrong. The lists of vices which he employed in his letters were probably intended to be uncontroversial and so to elicit immediate agreement from his readers. However, times change and some items in his lists now appear much more debatable than they were two millennia ago. They are now interpreted differently, and some attract more public moral opprobrium than others. It is, of course, those statements that are now controversial which attract much public debate. However, having now spent 20 years working with people with alcohol and other drug problems, it is St Paul’s inclusion of drunkenness in a number of these lists2 which has increasingly interested me over recent years.

Moderate alcohol consumption is seen as a normal part of contemporary western lifestyle. But even amongst those who do consider themselves to be Christians, the matter is not at all straightforward. Jesus was apparently accused by his opponents of being a drunkard (see eg Luke 7:34) and on this basis I have heard it suggested in a Sunday sermon that Jesus must himself have been drunk at times – a suggestion which attracted great controversy after the service!

Of course, drunkenness is not the only matter of concern. Whilst alcohol is associated with violence, family disharmony and other forms of antisocial behaviour, alcohol causes or is associated with a wide and diverse range of problems – social, psychological and biological – which may or may not be associated with overt drunkenness. Whilst the misuse of alcohol is recognised as a matter for social concern, our enjoyment of alcohol makes us ambivalent about these associated problems.

When it comes to drunkenness, we might still expect the majority of those who read Paul’s letters today to express disapproval. Amongst those who read the New Testament rarely or not at all, there might be much greater debate. While many still disapprove of drunkenness, it is seen by many others as being another way of having fun, of relaxing, and of getting away from the stresses and problems of today’s world.

It might well be that there is greater agreement about the ethics of drinking very large amounts of alcohol, or about the morality of very serious alcohol related problems. Slight intoxication at home with friends is one thing, but causing a death by drunken driving is quite another. But even amongst those who do consider themselves to be Christians, the matter is not at all straight forward.

Whilst there is much truth in this, it does not answer questions about how much is “too much” or about how likely and how serious problems have to be before they become ethically unacceptable consequences of drinking alcohol. Furthermore, it does not get to the heart of an important way in which our view of the whole subject has changed dramatically since the time of St Paul.

Whatever controversies about drinking and drunkenness there might have been, things changed most significantly in the 19th Century as the concept of “chronic inebriety” was medicalised and increasingly subjected to scientific scrutiny. Prior to this time, it is probably fair to say that drunkenness was not seen very differently from any of the other kinds of vice in St Paul’s lists. Christendom knew that drunkenness, like adultery and theft, was wrong. People shouldn’t do these things – but they did. All people were sinful and all needed forgiveness. All were called to amend their lives. Drunkenness was one thing amongst many for which people needed to repent. But the increasing medicalisation of the problem, concurrent with the much wider effects of the enlightenment on public discourse, changed this forever. Drunkenness, and other alcohol-related problems, came to be viewed not so much as primarily ethical issues, and certainly not as theological matters but rather as concerns of public health, public policy and public order.

Whilst the majority of people who get drunk are not in any commonly accepted sense “alcoholics”, perceptions of drunkenness have also been influenced by the development of the concept of “addiction”. This concept, extended to the use of a variety of other drugs and also to various behaviours in which no extrinsic chemical substance is involved at all, has been notoriously elusive of a universally agreed definition. However, it is now scientifically encapsulated in the concept of the dependence syndrome. The alcohol dependent person is understood as suffering from a bio-psycho-social disorder which importantly changes and constrains the usual experience of freedom of choice about drinking behaviour. The alcohol dependent person experiences withdrawal symptoms when they stop drinking and they experience a subjective “compulsion” to continue drinking. Because we usually do not consider people to be morally responsible for acts about which they have no freedom of volition, the concept of addiction or dependence introduces an important change in the way that drunkenness – or at least chronic drunkenness or “alcoholism” – is commonly viewed. To the extent that the alcohol dependent person is the subject of this “compulsion” they are not free moral agents, and their responsibility may be understood as diminished or removed.

Paradoxically, and perhaps partly because the individual is seen as responsible for their plight, the concept of addiction has not always led to moral sympathy for the addict. Perhaps this is partly because the individual is seen as responsible for their plight. If they hadn’t drunk too much (or perhaps if they hadn’t drunk at all) they would never have become alcohol dependent. However, I think that this lack of sympathy also concerns the emphasis that is placed upon the difference that is perceived between the addict or alcoholic and other people. Instead of being sinful as we are all sinful, the addict comes to be viewed as sinful in a different kind of way, or to a greater degree. In fact, the so called “moral model” has become the subject of much criticism in scientific and medical circles. The more enlightened view is to understand the addict as sick rather than sinful. I would suggest that this view owes more to the enlightenment than to Christian tradition. It is a morality which singles out the other person as different from self, rather than one which understands all human beings as sinful, including oneself. It is a morality which ignores or overlooks one’s own failings and draws attention to those of someone else.

Unfortunately, scientific and theological debate no longer take place in the same forum. Matters of religion are largely relegated by secular society to the private domain. As areas of academic discourse theology and science are discussed in completely different journals, conferences and common rooms, as though they had little to do with each other. The implication is clearly that theology is no longer considered necessary to a proper understanding of matters such as addiction and drunkenness. And yet, spirituality – largely as a result of the work of Alcoholics Anonymous and its sister organisations – is increasingly considered to be vital to provision of holistic treatment, and addictive disorders are viewed by many as being a spiritual problem. Theology has thus been replaced by science, and religion by spirituality. Does Christianity (or any of the world’s other major faith traditions) any longer have anything important to contribute to the debate?

It is my contention that Christian theology does have an important contribution to make to an understanding of addictive disorders – and particularly to an understanding of the ethics of alcohol use and misuse.

However, this contribution is best appreciated not by a narrow focus on scriptural texts making explicit reference to drunkenness, but rather by broader theological reflection on the phenomenon of alcohol dependence and addiction. In my book, Alcohol, Addiction and Christian Ethics, I have taken two Christian texts for detailed study, on the basis that they appear to reflect a phenomenologically similar experience to that of the subjective compulsion of alcohol dependence. The first of these is St Paul’s discussion of the divided self in Romans 7, and the second is Book 8 of the Confessions of St Augustine of Hippo, both texts which reflect an understanding of the ways in which individuals can struggle within themselves in respect of behaviour to which they aspire.

In Romans 7 (vv15-19), for example, St Paul writes:

“I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate. Now if I do what I do not want, I agree that the law is good. But in fact it is no longer I that do it, but sin that dwells within me. For I know that nothing good dwells within me, that is, in my flesh. …….I can will what is right, but I cannot do it. For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I do.”

And compare this with the experience of an alcohol dependent woman, married to an alcohol dependent husband, whose story was included in the “Big book” of Alcoholics

Anonymous:

“George tried many times to go on the wagon. If I had been sincere in what I thought I wanted more than anything else in life – a sober husband and a happy, contented home – I would have gone on the wagon with him. I did try, for a day or two, but something always would come up that would throw me.

“It would be a little thing; the rugs being crooked, or any silly little thing that I’d think was wrong, and off I’d go, drinking…… I reached a stage where I couldn’t go into my apartment without a drink. It didn’t bother me anymore whether George was drinking or not. I had to have liquor. Sometimes I would lie on the bathroom floor, deathly sick, praying I would die, and praying to God as I always had prayed to Him when I was drinking: “Dear God, get me out of this one and I’ll never do it again.” And then I’d say, “God, don’t pay any attention to me. You know I’ll do it tomorrow, the very same thing.””3

If we are honest, I think that we all have these kinds of experiences. It may not be quite as dramatic, and the implications might not be quite as serious, but we all find ourselves doing things that we know we shouldn’t do and then regretting it. We struggle to stop destructive patterns of behaviour and find ourselves doing the very things that we have decided in our own minds we will not do. We eat more than we know we need; even to the point of prejudicing our own health. We find ourselves sucked back in to particular arguments, or destructive relationships, when we have promised ourselves that we wont go there again. We spend time watching television when we know that work or family commitments require urgent attention. We spend money on things that we know we can’t afford. And so the examples go on – often known only to ourselves or to those closest to us – but all representing the same internal struggle to be the kinds of people that we desperately want ourselves to be.

Looked at in this way, it might be argued that we all have a subjective compulsion to do things that we don’t want to do. Perhaps it is even a characteristically human experience to have such internal struggles and to be aware of having them. It certainly is not unique to the experience of the addict or alcoholic. And even if the atheist or humanist might wish to choose a different language, these struggles have been the concern of theology for many centuries before they came to be a topic of scientific interest. For St Paul, the solution was clear:

“Wretched man that I am! Who will rescue me from this body of death? Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord!”4

He understood the grace of God in Jesus Christ as being the only way to become free from this struggle – and Augustine of Hippo went on to write in similar vein about the necessity of this grace to set us free from the struggle set up by the division of the human will against itself. A post-modern culture is much less happy to accept the particularity of this solution, but Alcoholics Anonymous adopted a not dissimilar, albeit not so Christocentric, understanding in the 2nd of its 12 Steps:

“We…. came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.”

The necessity of a “Higher Power”, whatever it might be, as a component of a spiritual recovery from alcoholism was to become fundamental to the philosophy of Alcoholics Anonymous, as detailed in the second of its 12 Steps:

“We…..came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.”

For St Paul and St Augustine, faith in Christ was the only pathway to freedom from the divided self.

Many men and women have found freedom from addiction through spiritual and religious experiences – but many continue to struggle despite their faith. On the other hand, secular programmes of treatment with no spiritual or religious component at all continue to benefit many. We must, therefore, be wary of proposing simple solutions such as those that require Christian faith, or exclude such faith, as a means of recovery from addiction. However, in one form or another, it would appear that grace is an important component of recovery, and grace is a theological concept. To separate theology and science in discussion about such matters is, therefore, I would argue, at least a highly impoverishing approach to a proper understanding of the nature of addiction.

To return to the broader problems in society of alcohol use and misuse, I would propose that theology still has important things to say. To imagine that the man or woman with a drinking problem is either the victim of their environment or the agent of their own catastrophe is equally simplistic. We are all both agents and victims, and Western culture fosters various kinds of dependence in various ways. Whilst we need to analyse such systems as matters of public health and public policy, theological models of these systems need to be formulated and articulated in the course of secular debate. Not to do so is to collude with the implicit assumption that such phenomena can be adequately understood within an essentially atheistic framework of understanding.

* A version of this article first appeared in ‘Borderlands’ – produced by St. John’s College, Durham

References

1 Corinthians 6:9-10, NRSV

2 See also Romans 13:13, 1 Corinthians 5:10-11, Galatians 5:19-21