In this month’s alert

“Supermarkets exhibiting the morality of a crack dealer” Select Committee told

The House of Commons Health Select Committee was told that “supermarkets are exhibiting the morality of a crack dealer” by expert witness Professor Martin Plant and he stated bluntly “Cheap alcohol kills people.” Professor Plant added ‘I think the option that the Chief Medical Officer and also the Scottish Government have picked of minimum unit pricing is very powerful because it has a trivial effect on the great majority of people who would only have to pay five or six pounds a year more for their alcohol; it would save 3000 lives a year; it would cut the number of days lost in absenteeism; it would cut hospital admissions and alcohol-related crimes by many, many thousands; it would also save a million pounds a year.”

The Committee has considered evidence from medical and public health experts, academics working in addiction and substance misuse research, and experts in the historical and geographical context of alcohol misuse.

Witnesses pointed out that the problem of alcohol-related harm is significantly underestimated.

Professor Ian Gilmore, President of the Royal College of Physicians, stated that the 8000 deaths per year from alcohol quoted by the ONS relate “almost entirely to alcoholic sclerosis. It does not pick up the accidents, the violence and so on. If you include cases where alcohol is named on the death certificate as a contributory cause then the fi gures rise to about 15,000 but if you criteria for obesity the figures would …. probably be about 300,000.”

Dr Peter Anderson said that Government policy had allowed alcohol to become much more affordable, with supermarkets selling alcohol at undercut prices, and that marketing had had a major impact: “…price and availability matters – if price goes down, consumption and harm go up, if availability is restricted there is less harm.”

The witnesses from the health lobby agreed that education and information campaigns on their own don’t work but that putting in good legislation and enforcing it would shift people’s behaviour, adding that regulatory controls on advertising would be much more effective than self regulation (as Dr Anderson put it, “don’t ask a bird to clip its wings”). Professor Gilmore suggested that tax relief on drinks industry advertising should be abolished, and that the resulting money could be used for public health campaigns run by the Government. Witnesses also suggested that focus should be put on the harms done to people other than the drinker with at least 15% of crime on Friday and Saturday night being alcohol-related. The Committee heard that 30% of patients have been drinking before an attendance at an A & E department, rising to 70% on a Saturday night, that 6% of ambulance calls were alcohol related (an 11% increase from last year) and that between 10pm and 2am in the morning on Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights 20% of ambulance work is alcohol-related.

The Committee considered the findings of Dr Petra Meier’s research for the Department of Health*, evaluating the effect different policies would have on drinking levels and associated harm, together with a research report produced by RAND for the European Commission which looked at the link between alcohol affordability, consumption and harms across the whole of the EU.

Dr Meier said that school based education, public service messages and product labelling were not very effective policies but that linking taxation to strength of alcohol was a very good idea in public health terms and Ms Rabinovitch, of RAND, agreed, saying that an increase in taxation where it leads to significant increases in price can have a very important effect in terms of reducing consumption and harm.

Discussion about point of sale information and layout of stores revealed differing views on the subject of separate alcohol areas in stores. Jeremy Beadles, of the Wine and Spirit Trade Association, said that the policy would increase alcohol sales if people had to go through a separate purchasing experience. This opinion was contrary to evidence from the Sheffield University research that the policy would result in a 40% decrease in sales.

The Industry view on minimum pricing was that heavy drinkers are less sensitive to pricing than moderate drinkers and the industry also asserted that alcohol was already more expensive in the UK than in other EU countries. However, Mr North, speaking on behalf of Tesco, stated:

“we are very prepared to play an active and constructive role in discussions on minimum pricing, or, indeed, the whole issue of pricing … for that to be effective it has to be done across the industry rather than on a unilateral basis.” *Independent Review of the effects of alcohol pricing and promotion.

Comments

Dr Peter Anderson: A unit of alcohol –

“In scientific terms it is eight grams or ten millilitres of pure alcohol and that equates to a half pint of ordinary beer, a small glass of wine (about 110 or 120 millilitres of 10% wine) and a single pub measure of spirits. However, as you know, glasses are getting bigger and drinks are getting stronger. A significant number of pubs and restaurants will offer only 250 millilitre glasses of wine which is one third of a bottle. If it is a 14% red wine that will contain about four units……We should think rather more in terms of risk related to consumption…there is no safe level; there is a lower risk of harm.”

Alcohol related harm as a problem for the NHS:

“…there are nearly a million alcohol related hospital admissions a year, you convert the 75%-plus of presentations after midnight (which) are alcohol related, the burden on the NHS is absolutely huge. It is a preventable problem.”

Dr Petra Meier:

“50p per unit minimum price would add just £12 a year for moderate drinkers but £163 a year or more for someone drinking at harmful levels.”

Findings from Dr Meier’s research:

- Minimum pricing would affect supermarkets and off licenses more than bars, clubs and restaurants because they tend to sell alcohol at cheaper prices.

- 50p minimum would prevent 3,400 deaths and reduce the number of hospital admissions by 98,000 per year.

- Different tax rates for strengths of alcoholic drinks would have a positive effect on public health and reduce binge drinking.

Professor Robin Touquet:

“…alcohol has, pro rata, got cheaper;… the availability, and the perniciousness is that young people feel, “No government would give 24-hour availability at cheap prices if alcohol was dangerous; after all, they would not do that for heroin or cocaine. They do it for alcohol; alcohol must be safe.” … it sends a wrong message to the young that alcohol must be safe; and alcohol is not safe.”

Expert witnesses on the health side have, so far, included:

Professor Ian Gilmore, President, RCP Dr Peter Anderson, Public Health Consultant Professor Martin Plant, Professor of Addiction Studies, UWE Dr James Nicholls, Senior Lecturer, Bath Spa University Dr James Kneale, Lecturer in Human Geography, UCL Professor Mike Kelly, Director, CPHE, NICE Dr Lynn Owens, Nurse Consultant, Liverpool PCT Professor Robin Touquet, St Mary’s Hospital, London Dr Petra Meier, Senior Lecturer in Public Health, Sheffield University Ms Lila Rabinovitch, Analyst, RAND Europe

And representing the industry:

Mr David North, Community and Government Director, Tesco Mr Jeremy Blood, Chief Executive, S & N, BBPA Mr Jeremy Beadles, Chief Executive, WSTA

What the public health witnesses felt should be done to reduce alcohol-related harm:

- Minimum unit price

- Adjustments to the tax structure

- Take action on price promotions and city centres

- Have separate areas for alcohol in supermarkets, with separate tills

- Restrict the marketing of alcohol

- Increase government work in licensing, labelling and taxation

- Have a national strategy based on bringing down overall consumption levels in the population as a whole, especially among people who consider themselves to be sensible drinkers

- Take public health into account when granting licenses

- Make a major investment in helping family doctors and nurses do more to help people who are at risk in drinking

- Increase numbers of alcohol health workers – in primary and secondary care

- Increase screening intervention in primary care

- Change culture to recognise alcohol as a population-based problem

- Have a designated clinical lead who can help patients navigate systems

Leading Health Charities call for ban on advertising alcohol price promotions

A coalition of leading UK public health organisations have joined forces to call for a ban on the advertising of alcohol sold on promotion. The Alcohol Health Alliance, which includes the IAS, Alcohol Concern and the Royal College of Physicians, wants to see an end to all adverts which promote alcohol on the basis of low cost. This would include discounted alcohol, multi-buy promotions and buy-one-get-one-free special offers. The Alliance hopes that such a move would reduce competition between supermarkets to sell alcohol cheaply and below cost in order to increase consumption. The Alliance wants the ban to include advertising by supermarkets, in which alcohol on promotion is one of a number of products advertised.

In their submission to the Advertising Standards Authority’s comprehensive review of advertising codes, the Alliance requests that ‘advertisements must not include alcohol sales promotions and must not imply, condone or encourage immoderate drinking’. The Alliance believes that the advertising of alcohol sales promotions encourages competition between retailers to heavily discount alcohol products and encourages below-cost or ‘loss leading’ sales, in turn leading to higher alcohol consumption and an escalating public health crisis.

Other European countries, such as France and Norway, have a total ban on all alcohol advertising on television and billboards.

Alcohol Concern Chief Executive Don Shenker said:

“Supermarket price wars played out in the media are pushing the costs of alcohol down and presenting alcohol as an everyday household item.”

“By promoting heavily discounted alcohol, retailers are encouraging bulk buying and contradicting the safe drinking messages the Government is trying to promote, and which they claim to support.”

Royal College of Physicians President Ian Gilmore said:

“As a society we know we have a drink problem and to allow alcohol to be marketed like soap powder is simply not acceptable.”

“We have the evidence that young people are influenced by marketing and know that other countries are taking firm action. We must follow suit.”

Institute of Alcohol Studies comment

Aneurin Owen

Gordon Brown’s almost instant dismissal, on the 16th March, of the Chief Medical Officer’s call for a 50p minimum price per unit of alcohol is symptomatic of an underlying attitude across Government departments that needs to be challenged vigorously.

The fundamental approach of the Alcohol Harm Reduction Strategy and many other Government initiatives has been to target the ‘excessive drinking of a minority’ without impinging on the freedoms of the majority – the mantra that was repeated by Gordon Brown in his comments. This rhetoric is to be found across all government initiatives relating to the control of alcohol, its promotion and sale, as witnessed in the recent consultation documents such as that for the new code of practice for alcohol retailers. It is surely time to recognise that the harm caused by alcohol is better represented by the notion of a continuum of harm across the total spectrum of the population and across the total spectrum of consumption.

In this edition, the article on increased cancer risk highlights the risks associated even at low levels of alcohol consumption and we highlight a Scottish survey indicating that even 8 to 14 weekly units of alcohol give rise to a higher number of hospital bed days occupied.

Total population approaches have long been advocated and the current debate surrounding the introduction of a minimum price highlights the difficulty of introducing proportionate measures that will reduce harm. There is widespread support for minimum pricing as an instrument to reduce the availability of low-cost alcohol and supporters of minimum pricing believe that it is the best price policy because it will affect heavy drinkers whilst having less effect on moderate drinkers. The controversy and the debate will continue for the forseeable future, as highlighted in Jack Law’s article. There is a long way to go, but at least the relationship between price, consumption and harm is now fixed in the consciousness of retailers, policy makers and health advocates alike.

Southampton study highlights risks of daily drinking

Daily or near-daily drinking is putting more people at risk of alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) than binge drinking, according to a study carried out by researchers at the University of Southampton. The study, led by Dr Nick Sheron, found that patients with alcoholic liver disease started drinking at a significantly younger age (around 15 years old) and had significantly more drinking days and units than non-ALD patients from the age of 20 onwards.

The study also highlights the need for identifying people who are likely to develop alcohol-related illnesses at a much earlier stage and recommends that more attention should be paid to the frequency of drinking in heavy social drinkers.

Responding to the study, Imogen Shillito, of the British Liver Trust, fully supported the need for at least two alcohol-free days each week and pointed out that it was impossible to tell which of us would remain unharmed by alcohol. “If you think you are at risk you should visit your GP,” she said. Since 1991 the death rate from alcohol-related illness has doubled and each year over 60,000 people are admitted to hospital because of alcohol. The research was published in the scientific journal ‘Addiction’.

A quarter of adults in England are hazardous drinkers

“An estimated quarter of adults are at risk of damaging their mental or physical health because of their drinking habit.” Tim Straughan

One in three men and one in six women – a quarter of all adults in England – are estimated to be hazardous drinkers, says a new report from The NHS Information Centre.

In 2007, the drinking habits of 33% of men and 16% of women were classed as hazardous, which means their established drinking patterns put them at risk of physical and psychological harm. 6% of men and 2% of women were estimated to be harmful drinkers, the most serious form of hazardous drinking, which means they are likely to suffer physical or mental harm, such as liver disease or depression.

The report ‘Statistics on Alcohol: England, 2009’, brings different information on alcohol together from a variety of sources. It also includes figures on drinking dependence that allow a comparison between 2000 and 2007 to be made. The report estimates that in 2007 9% of men and 4% of women showed some sign of alcohol dependence. The figure for men is slightly lower than in 2000 when 11.5% of men showed signs of drinking dependence. The figure for women is not significantly different from 2000.

The report also shows:

The annual number of alcohol-related admissions to hospital in England rose by nearly 70% in five years, to reach just over 863,000 in 2007/8. These figures use a new methodology reflecting a substantial change in the way the impact of alcohol on hospital admissions is calculated. Previously, the calculation counted only admissions for reasons specifically related to alcohol. The new calculation, for which the methodology is described in the report, includes a proportion of the admissions for reasons that are not always related to alcohol, but can be in some instances (such as accidental injury). In England in 2007, 34,429 prescription items for drugs for the treatment of alcohol dependency were prescribed in primary care or NHS hospitals and dispensed in the community. This is an increase of 31% since 2003, when there were 102,741 prescription items.

The report also includes survey information about attitudes to alcohol. It estimates that, in 2007, 17% of school pupils aged 11 to 15 thought it was okay to get drunk at least once a week. However, the proportion of pupils who have never had a proper alcoholic drink was 46% in 2007, compared to 39% in 2003. NHS Information Centre Chief Executive, Tim Straughan, said: “An estimated quarter of adults are at risk of damaging their mental or physical health because of their drinking habit. The report shows a significant amount of people are at risk of actual harm to themselves, which in turn results in more work for the NHS.”

A copy of the report ‘Statistics on Alcohol: England, 2009’ can be downloaded at: www.ic.nhs.uk/pubs/alcohol09

Drink a day increases cancer risk

A glass of wine each evening is enough to increase your risk of developing cancer, women are warned

Consuming just one drink a day causes an extra 7,000 cancer cases – mostly breast cancer – in UK women each year, Cancer Research UK scientists say. The risk goes up the more you drink, whether spirits, wine or beer, the data on over a million women suggests.

Overall, alcohol is to blame for about 13% of breast, liver, rectal, mouth and throat cancers, the researchers say.

They estimate that about 5,000 cases of breast cancer in the UK – 11% of the 45,000 cases diagnosed each year – can be attributed to women’s consumption of alcohol.

The study looked specifically at women who consumed low to moderate levels of alcohol – defined as three drinks a day or fewer.

Over the seven years of the study, published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, a quarter of the 1.3 million women reported drinking no alcohol.

Of those who did drink, virtually all consumed fewer than 21 drinks per week, and an average of 10g of alcohol per day, which is equivalent to just over one unit of alcohol found in half a pint of lager, a 125ml glass of wine or a single measure of spirits. Nearly 70,000 of the middle-aged women developed cancer and a pattern emerged with alcohol consumption.

One too many?

Consuming one drink a day increased the risk of all types of cancer by 6% in women up to the age of 75. The rates for individual cancers varied, with one drink a day causing a 12% rise in the risk of breast cancer, a 10% rise in rectal cancer, a 22% rise in gullet cancer, a 29% rise in mouth cancer and a 44% rise in throat cancer.

On a population scale, this would mean 15 extra cases of these cancers diagnosed for every 1,000 women – comprising 11 breast, one mouth, one rectal cancer and 0.7 each for cancers of the gullet, throat and liver. The government says no amount of alcohol is fully safe, but recommends women should drink no more than two to three units per day on a regular basis to have a lower risk of any harm to health.

For men the recommended limit is no more than three to four units per day.

Mixed Messages

Lead author Dr Naomi Allen from the University of Oxford said her work would help the government assess whether the limits should be changed, although the study did not look at men.

“The findings of this report show quite strongly that even low levels of drinking that were regarded to be safe do increase cancer risk.

“About 5% of all cancers in the UK are due to drinking something in the order of one alcoholic drink a day.”

She said there was confusion about how much people should drink. Research has shown a daily tipple can be good for the heart. And factors other than alcohol pose a bigger risk for certain cancers.

“It is up to individual people to make their own decision. All of us to some extent have to weigh up the risks and take some responsibility for our health,” said Dr Allen.

A Department of Health spokesman said: “We keep our guidance on sensible drinking under review. We currently advise on a lower risk drinking limit and that drinking above this level could be harmful.

“There is no completely safe level of drinking but this lower level reflects the known risks including breast cancer, which is partly why there is a lower drinking limit for women.

“We look forward to examining this research in more detail.”

Dr Sarah Cant of Breakthrough Breast Cancer said:

“We already know that drinking alcohol can increase your risk of breast cancer. This study suggests that for women over 50 even drinking moderate amounts of any type of alcohol can have many health consequences, including a greater chance of developing breast cancer. Around 80% of breast cancer cases are diagnosed in women aged over 50, so limiting how much you drink is one step you can take to try to reduce your risk of developing the disease.”

Breast cancer is now the most common cancer in the UK. Each year almost 45,000 women are diagnosed with breast cancer. A woman’s lifetime risk for breast cancer in the UK is one in nine.

“We already know that is one step you can take developing the disease.”

8 to 14 weekly units of alcohol boosts overall tally of days spent in hospital

Drinking between 8 and 14 units of alcohol a week boosts the total number of days spent in hospital, researchers find

Twenty one weekly units is the government’s recommended maximum weekly tally of alcohol for men.

A new study found that men drinking over 22 units a week had a 20% higher rate of admissions into acute care hospitals than non-drinkers. But relatively low levels of alcohol consumption gave rise to a higher number of bed days. Drinkers of eight or more weekly units spent longer in hospital than non-drinkers, with length of stay progressively increasing, the higher the weekly consumption. Those drinking the most chalked up a 58% higher use of beds. The number of admissions for stroke, and more time spent in hospital as a result, started with a weekly tally of 15 units, and progressively increased the more weekly units were consumed.

Those drinking 22 or more weekly units had more admissions for respiratory illness, but they had the lowest rates of admission for coronary heart disease. Non-drinkers had the highest rates of admission for this. Men drinking 22 or more units a week had more admissions for mental health problems. But non-drinkers had a higher rate of admissions for mental ill health than those who drank between 1 and 14 units a week.

The authors conclude that alcohol has a “notable effect” on health service use and therefore, overall costs to the NHS.

Alcohol consumption and use of acute and mental health hospital services in the West of Scotland Collaborative prospective cohort study

Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2009

doi 10.1136/ jech.2008.079764

Scots alcohol related deaths double what previously thought – one alcohol death every three hours

New research shows alcohol-related illnesses could be killing 1 in 20 Scots – twice as many as previously thought

The study totalled the proportion of 53 different causes of death – ranging from stomach cancer and strokes to assaults and road deaths – in which alcohol consumption played a part, to show that nearly 3,000 deaths in 2003 were alcohol-related. This is double the figure for deaths from illnesses caused almost entirely by alcohol consumption alone, such as alcoholic liver disease. It means one Scot may be dying from alcohol-related causes every three hours.

While alcohol-related deaths accounted for five per cent of all deaths in Scotland, this proportion rises to more than a quarter of deaths in men and a fifth of women aged 35-44. In addition, around 41,414 people were discharged from hospital due to alcohol consumption – more than one in twenty (7.3 per cent) of patients over 16, and 50 per cent higher than figures based on wholly attributable conditions.

Nicola Sturgeon, Health Secretary, said:

“This research shows that alcohol misuse is taking an even higher toll on Scotland’s health than previously thought. To have one in 20 Scots dying from alcohol-related causes is a truly shocking statistic. Drinking alcohol is part of Scottish culture, but it’s clear that many people are drinking too much and damaging their health in the process.

Alcohol misuse is the biggest public health challenge we face and the Scottish Government has made crystal clear our determination to get to grips with it.”

Cancer deaths accounted for just over a fifth (21.7 per cent) of all alcohol attributable deaths. A total of 2,374 of the 2,882 deaths (82.4 per cent) linked to alcohol were in people under the age of 75. And of these, 1,080 deaths were people under the age of 55.

The calculations are based on consumption data from the Scottish Health Survey 2003, updated to reflect the increasing strength of alcoholic drinks. Conditions were identified where alcohol increased the likelihood of developing the condition and this information was applied to consumption patterns to calculate the proportion of deaths from a particular condition attributable to alcohol. New Scottish Health Survey data due for publication later this year will allow updated mortality figures to be calculated. The study, published by ISD Scotland, also indicated that 1,493 heart disease deaths may have been prevented by low levels of alcohol consumption, although drinking even at low levels was found to be a risk factor for almost all the other conditions. Furthermore, the positive effects of low consumption in relation to heart disease were cancelled out by higher consumption.

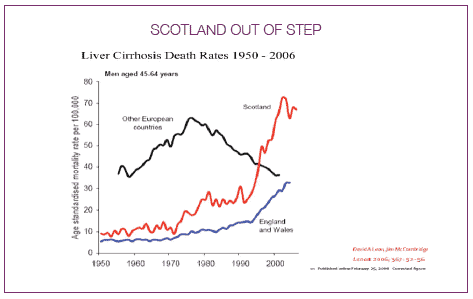

Scotland out of step with European levels of alcohol related harm

Jack Law, Chief Executive, Alcohol Focus Scotland, reports

Alcohol misuse costs Scotland a staggering £2.25 billion per year. Someone dies every 4 hours from an alcohol-related disease – equivalent to 33 full double decker buses a year.

Scotland has the highest rates of liver disease deaths in western Europe. Alcohol-related death rates in Scotland are around double the rates for the UK as a whole. At a local level, Glasgow City had the highest alcohol-related death rate among both men and women in 1998-2004. Alcohol is involved in 70% of assaults. It’s conservatively estimated that around 65,000 children are living in families where there are alcohol problems. “Changing Scotland’s Relationship with Alcohol: A Framework for Action” shows that the Scottish Government is taking seriously the need to address our drinking culture with bold action to reverse unprecedented levels of alcohol-related health and social harm. It focuses on proposals to reduce consumption through regulating price and availability, as well as actions to support families, improve support and treatment, and promote positive attitudes and choices.

We particularly welcome the long overdue commitment to end irresponsible alcohol promotions in shops and supermarkets. Instead of buying the four cans of beer we actually want, we leave with a case because it was so deeply discounted, so heavily promoted and displayed at the entrance to the store that it’s difficult to resist.

While it is clear there is no magic bullet to tackling alcohol problems, the evidence is clear that price is closely linked to consumption and consumption to harm. Introducing a minimum price per unit of alcohol will reduce consumption and therefore reduce health and social harm.

What is minimum pricing?

Minimum pricing is the lowest price at which any alcohol product can be sold. The price is set based on the alcohol content (number of units) of the product. So, the higher the number of units in a bottle, the higher the minimum price will be. Cheaper alcohol tends to be bought more by harmful drinkers than moderate drinkers, and is shown to be attractive to young people and those under the legal age. So a minimum price policy is beneficial in that it targets the drinkers causing the most harm to both themselves and society whilst having little effect on the spending of adult moderate drinkers.

Research by the University of Sheffield research for England and Wales shows that there would be a £12.93bn value of harm reduction in terms of employment, criminal justice, and health costs if minimum pricing was set at 50p per unit.

Why do we need it?

Over the past 50 years the real price of alcohol has fallen. With the introduction of more liberal licensing legislation; this has led to alcohol being sold in more places and for longer periods of time. This has increased competition between retailers who have responded by cutting prices and offering deep discounts and promotions. The result is that alcohol is available at pocket money prices.

So how will minimum pricing reduce harm?

If we want to reduce the level of alcohol-related harm in Scotland we need to reduce overall consumption of alcohol. There is a growing body of evidence which shows that price increases can have a substantial impact on reducing consumption, and consequently harm. Based on estimates by the Academy of Medical Sciences, a 10% rise in alcohol price would save the lives of 479 men and 265 women in Scotland every year.

Do other countries have minimum pricing for alcohol?

A number of countries in Europe, including Belgium, France, Greece, Portugal and Spain, have legislation banning below-cost selling. However, minimum pricing schemes for alcohol in which minimum prices are fixed by public authorities are less common. Canada is one country that has a well established minimum pricing scheme for alcohol.

What do we stand to gain if minimum pricing for alcohol is introduced?

The University of Sheffield study into pricing policies concluded that:

- Pricing policies can be effective in reducing health, crime and employment harm.

- Pricing policies can be targeted, so that those who drink within recommended limits are hardly affected and so that very heavy drinkers, who cause by far the most alcohol-related harm, are most affected.

- Minimum unit pricing and discount bans could save hundreds of millions of pounds every year in NHS, crime and employment costs.

If policy makers wish to see the greatest impact in terms of crime and accident prevention, through reducing the consumption of 18-24 year old binge drinkers, they need to consider policies that increase the prices of cheaper drinks available in pubs and clubs as well as supermarkets. Dispelling the myths which have been put forward by some drinks producers and retailers who are in opposition to minimum pricing:

Moderate drinkers are not being ‘penalised’. If you drink within the sensible drinking guidelines, you will barely notice any difference in cost. Price increases will affect the heaviest drinkers the most.

Scotland’s alcohol problems are not restricted to underage and chronic drinkers. 1 in 2 men and 1 in 3 women are exceeding the recommended guidelines. People in all age groups and backgrounds are drinking in a way that is harming themselves and others. We are all affected so we all need to be part of the solution.

People on low incomes will not be ‘penalised’ – moderate consumers, irrespective of income levels, will notice very little difference in terms of cost. What will be noticeable is a significant health improvement and reduction in alcohol-related deaths amongst the most deprived members of society who account for 64% of alcohol related deaths, and are six times more likely to be admitted to hospital with an alcohol-related diagnosis than those from the most affluent areas.

This is not a tax. The extra money will go to retailers, not the government. Using taxation as a price lever has not been successful in the past as some retailers have not passed on the increase to their customers.

It does not contravene competition law.

There is no evidence that people will cross the border to buy alcohol in England. This would be costly and time consuming, and only certain drinks would be increasing in price.

We have reached the point where prices must increase for Scotland’s damaging relationship with alcohol to be re-balanced. Change won’t happen overnight. But the combined efforts of Government, health and police services, the alcohol industry, licensed trade and the voluntary sector should ensure significantly fewer Scots’ lives are blighted by alcohol misuse.

UK doctors back calls for minimum price of alcohol

Doctors at the BMA’s annual conference in Liverpool also backed calls to introduce a minimum price for a unit of alcohol.

Proposing a motion which included calls for clearer labelling and a total ban on alcohol advertising, Dr Chandra Mohan from Barking, Havering and Brentwood, said:

“People drink alcohol in different patterns and for different reasons, so a multi-directional approach is needed to address these problems. We need clearer labelling of alcoholic products indicating alcohol content and unit value. We need to call on our Government to stop making excuses, to follow the plans of their Scottish colleagues and introduce a minimum price for a unit of alcohol.”

Dr Peter Terry, Chairman of the BMA in Scotland, said he welcomed his “UK colleagues’ support for the approach being taken in Scotland to tackle the serious and significant social and health costs of alcohol. Doctors witness the devastation of alcohol on patients and the crippling effect it is having on the NHS. With this ringing endorsement from the medical profession, I hope that politicians of all parties can back the Scottish Government’s alcohol strategy and support legislation on alcohol pricing.”

Dr Mohan quoted research published in a recent issue of the Lancet which stated that setting a minimum price of 50 pence per unit would increase moderate drinkers’ average weekly spend on alcohol by only 23 pence per week, but would decrease consumption by underage and heavy drinkers by 7.3% and 10.3% respectively.

The motion debated read:

That this meeting deplores the increasing burden of alcohol-related diseases and complications on our nation’s health. We:

i) support the introduction of a minimum price for a unit of alcohol;

ii) believe that a minimum pricing strategy would not unduly disadvantage responsible alcohol consumers;

iii) call for all alcoholic beverages to have clearer labelling indicating alcoholic content and unit value;

iv) call on the BMA to lobby government for a total ban on alcohol advertising in the media;

v) demand that revenue obtained from increased prices should be used for the prevention of alcohol misuse and the rehabilitation of alcohol abusers.

Chris Huhne acts on minimum pricing

Early Day Motion 1284 (Chris Huhne MP, 2 April 2009) calling for the introduction of a minimum price for a unit of alcohol:

“That this House notes the recommendations made by the Chief Medical Officer in his Annual Report 2008 to introduce a minimum price per unit of alcohol;

further notes evidence of a link between price and level of consumption;

recognises the damage caused by alcohol misuse to individuals, families and society;

further recognises the concept of `passive drinking’ or the consequences of one person’s drinking on another’s well-being;

acknowledges that alcohol misuse costs the UK economy up to 25 billion per year, including alcohol related health and crime costs;

further acknowledges that 80 per cent. of people think that more should be done to tackle alcohol abuse in society;

and calls on the Government to take steps to end the deep discounting and loss-leading sales of alcohol products and to make careful consideration of the recommendations of the Chief Medical Officer to implement a minimum price for alcohol as a means to do so.”

For details see: http://edmi.parliament.uk

Drunks – to treat or to punish?

As the Commons Health Select Committee investigated the adequacy of the NHS response to alcohol problems, the ethical question of how society, including the health service, should respond to people with drinking problems resurfaced.

Alcohol consumption and its consequences for the drinker and others have, of course, been long-standing sources of controversy, mainly because of the range of ethical questions and dilemmas to which they give rise. What are the rights and responsibilities of drinkers in regard to their own health and the well being of others? Are drinkers who get into trouble and experience alcohol problems paying the price of their own irresponsibility or are they the unfortunate victims of a medical condition over which they have little or no control? Is it the duty of the state to deter and punish alcohol misuse or to provide treatment and support for those who experience its effects? Should the person found drunk in the street be picked up by the police car or the ambulance?

The latest round of debates began with the question of the ethics of allocating organs for transplant to people who had damaged their livers by drinking excessively. Then a Think Tank proposed that the costs of being admitted to hospital “to sleep off alcoholic excess” should be met by the drinkers themselves, not the NHS. Meanwhile, former Work and Pensions Secretary, James Purnell, proposed that people dependent on alcohol or other drugs, who refuse to go on a course of treatment, could have their social benefits cut.

Liver Transplants

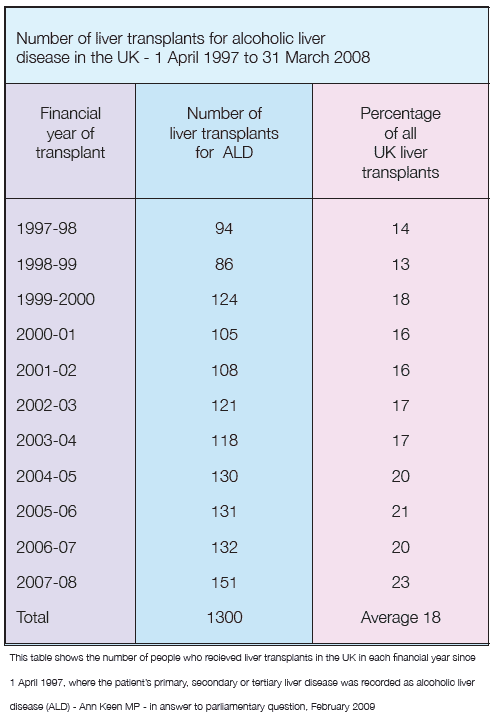

The argument over who is entitled to a liver transplant was prompted by the publication of figures showing that increasing numbers of the livers available for transplant are being allocated to patients with alcohol-related liver disease. Whereas in 1997/8, 14 per cent of liver transplants were for alcoholic liver disease, by 2007/8 the proportion had increased to 23 per cent. NHS statistics show that alcoholic liver disease is the main contributor to the 19 per cent increase in alcohol-related deaths between 2001 and 2007. Deaths from alcoholic liver disease rose by 31 per cent during this period.

While the epidemic of alcoholic liver disease is increasing demand for donated organs, not everyone accepts that patients whose need for a transplant is due to their alcohol consumption deserve to receive one. The Observer newspaper quoted the mother of a young woman whose organs helped to keep five people alive after she died objecting strongly to donor organs being given to people with serious alcohol problems.

Eunice Booker, whose 26-year-old daughter, Kirstie, died in a car crash in 2006, was reported as saying:

“I find it offensive that one in four of the livers donated go to alcoholics. If there are two people side by side wanting a liver, and both have the right tissue match, and one is an alcoholic and one isn’t, there’s no contest – you take the one who’s not an alcoholic, they are more entitled.”

Some of the hostility to transplants for alcoholic liver disease arises from alcohol harm being seen as self-inflicted. There is also the George Best problem; patients with drinking problems returning, like the late footballer, to drinking heavily after they have received a new liver.

Dr Tony Calland, Chairman of the British Medical Association’s Medical Ethics Committee, said surgeons are within their rights to refuse transplants to anyone with alcohol-related liver disease if they do not demonstrate a genuine desire to stop drinking.

Don Foster MP, the Liberal Democrat Shadow Culture Secretary, who obtained the figures, commented that his decision to release them “was not an attempt to provoke an argument about who was most deserving of medical resources but rather to highlight the serious consequences of society’s relationship with alcohol.”

Mr Foster said that “as a politician, and a flawed human being,” he found the idea that doctors should make moral judgments about whether a person deserved medical treatment abhorrent. Not least, he said, because he recognised that he had not always lived a blameless life when it came to his own health. However, at the same time, we could not continue to ignore the fact that hospital admissions related to alcohol rose by 57 per cent over the past five years to almost 800,000. Such growth, he said, was clearly unsustainable in the long term.

Mr Foster said the answer was to introduce a system of minimum prices for a unit of alcohol, which, he said, would cut consumption and the numbers of people with alcohol related disease requiring treatment.

Charging drinkers for treatment

The idea of charging drinkers the cost of their hospital stay came from the centre-right think tank Policy Exchange. In a report “Hitting the Bottle” the think tank argued that as the harm from alcohol was now at an epidemic level and costing the NHS nearly £3 billion a year, with hospital admissions for alcohol doubling in a decade, the Government should now commit to a review of its entire strategy for tackling the harms from alcohol. In particular, Policy Exchange recommended that the costs of being admitted to hospital “to sleep off alcoholic excess” should be met by the individuals concerned, not the NHS.

The Think Tank argued that those admitted to hospital for less than 24 hours with acute alcohol intoxication should be charged the NHS tariff cost for their admission, of £532. This amount would be reduced for those paying the costs of their own ‘brief intervention’ alcohol education and awareness course. Such interventions, it said, were proven to reduce both alcohol consumption and future health problems.

There should be a greater focus on policing public drunkenness and the use of Penalty Notices for Disorder (PNDs), so that more people are fined for being drunk. More people suffering with alcoholic excess are now admitted to hospital than are dealt with by the police. The increased use of PNDs should be accompanied by a national roll out of Alcohol Diversion Schemes, moving those issued with PNDs into ‘brief intervention’ alcohol education and awareness courses.

In view of the huge burden placed on the health service by people who are intoxicated, many may be sympathetic to the idea of recovering the costs of a short hospital stay from those whose only real problem is that they are drunk and who are using the facilities of the NHS simply as a soberingup station, courtesy of the tax-payer. However, on the same basis, it could be argued that people should also be charged for using police cells in the same way, and in relation to both police and NHS facilities, the same problem would arise as to where exactly the line was to be drawn. Would a drunk who was kept in hospital for more than 24 hours while the possibility of a head injury was investigated also be charged for their stay? And then there is the problem of enforcement. What would happen if the drunk patient refused to pay, or was unable to pay?

Alas, the Policy Exchange report is not very informative about the practicalities of implementing its recommendations, suggesting that the idea of getting the government to charge drunks for their stay in hospital may not have been wholly serious.

Benefit cuts for alcohol and drug patients?

Another proposal which looks much more serious, partly because it emanates from the Government itself, is the idea of encouraging people dependent on alcohol or other drugs to seek treatment by threatening to cut their welfare benefits if they refuse. Certainly the proposal looked sufficiently serious for some of the major players in the alcohol and drug fields, such as Alcohol Concern, to lobby vigorously against it.

The plan to cut the social benefits of unemployed drug and alcohol addicts appeared as part of the Welfare Reform Bill, introduced into the House of Commons by then Work and Pensions Secretary, James Purnell.

The Bill constitutes the latest instalment of the Labour Government’s New Deal Programme. Essentially, the concept is that, as a key part of the commitment to promote full employment, the benefit system will be turned from a passive provider of financial support to the unemployed and others suffering hardship, into a tool to promote engagement in the labour market. The intention is that the benefits system will offer support tailored to the particular individual to help them move back into work.

One of the features of the present situation, however, is the high number of what have been called the ‘invisible unemployed’, people of working age who are out of work, but who are not registered as unemployed but, rather, as unable to work through sickness or disability and who thus receive incapacity benefit.

The number of people receiving incapacity benefit has grown substantially, mainly, some critics have suggested, because it is a convenient way for the Government to disguise the true level of unemployment.

The system has also been attacked for being open to abuse and exploitation. In 2008, one of the Government’s own welfare advisers alleged that fewer than a third of the 2.7 million people claiming incapacity benefits were legitimate claimants. Many, he said, were actually working illegally while receiving the benefit. In response, a spokesman for the Department of Work and Pensions said “…we agree … that there are many more people who could and should be supported to move off benefits and into work. We … have already committed to replacing incapacity benefit and introducing a new medical test that places the emphasis on what work a person can do, rather than what they can’t.”

This is where the Welfare Reform Bill and the proposal to cut benefits of people dependent on alcohol and other drugs come in, for, as the White Paper on the Bill explained, for a number of people the biggest barrier to participating in the labour market is their use of drugs. The provisions of the Bill were then extended also to cover people whose drug of choice was alcohol. In recent years, around 40,000 – 50,000 people have been receiving incapacity benefits on the basis of a primary diagnosis of alcohol dependence, with a similar number receiving benefits on the basis of drug dependence.

The package of incentives and disincentives aimed at drug and alcohol misusers, to encourage them back into the workforce, includes requiring compulsory drugs tests and compliance with a rehabilitation plan for problem users receiving benefits, with the threat that failure to comply may result in loss of benefit.

Opposition to proposals

The Government’s plans to encourage drug and alcohol misusers back into work prompted a generally hostile reaction from the major alcohol and drug agencies.

For Alcohol Concern, Don Shenker condemned the proposal to make receipt of benefit conditional on seeking treatment or work as “counterproductive”.

He said:

“People with alcohol dependency issues require financial stability to seek, undergo and move away from treatment. Any threat that welfare benefits will be cut simply adds to the risk of relapse. In addition, requiring someone to undergo treatment requires that treatment services are available and the latest research shows only 1 in 18 alcohol dependents are able to access treatment, making these plans potentially unworkable. While the Secretary of State is right to want to support alcohol dependents into treatment, making welfare benefits conditional on treatment or work is misguided.”

The Royal College of Psychiatrists and the civil rights lobby group ‘Liberty’ also joined the attack, protesting that the proposals amounted to a gross intrusion into privacy and jeopardised patient confidentiality, and in any case were based on a fundamentally flawed understanding of the nature of drug dependence.

In a briefing on the Bill to the House of Lords, the Royal College and Liberty stated that the proposals would

“discourage many problem drug users from applying for benefits and may mean a number of people will withdraw from the system to ensure that their dependency does not become public. Many people dependent on drugs hide the problem from their friends and family and, indeed, do not even admit their addiction to themselves. Imposing what, in effect, amounts to forced treatment also shows a failure to understand the fundamental nature of addiction and the method by which it is treated. These provisions are likely to act as a further barrier to employment; may increase the risk of social exclusion; and risk increasing crime rates and entrenching the cycle of dependency.”

Some, however, may wonder if it is not actually the Royal College and other critics of the Bill who have a questionable understanding of the nature of addiction and of the other issues involved. The arguments about patient confidentiality and alcohol and drug dependents being in denial may be thought to be strange ones, given that the question arises in relation to people claiming benefits precisely on the basis of a medical diagnosis of alcohol or drug dependence. And forcing people to confront their dependence on alcohol and other drugs and to do something constructive to overcome the problem is normally accepted as a legitimate, indeed indispensable, element of the social response to alcohol and drug dependence.

In the criminal justice system, for example, the return of the driving licence to drink drive offenders with a serious alcohol problem is conditional upon their providing convincing evidence to the authorities that they have overcome their problem and are fit to drive.

The same principle of conditionality applies in workplace alcohol and drug programmes. Crudely expressed, these programmes normally offer substance abusing employees a hobson’s choice between agreeing to overcome their dependence by, for example, undergoing a treatment programme, or accepting normal discipline, which would often mean being fired. Far from being attacked as counterproductive intrusions into privacy, likely to entrench dependence and bring about relapse, workplace programmes are promoted by bodies such as Alcohol Concern as highly desirable responses to alcohol and drug problems. Indeed, in one of its major reports on alcohol, the Royal College of Psychiatrists itself claimed that “in companies where such policies exist and are genuinely operated, the extra motivation provided by the opportunity to remain employed greatly enhanced treatment outcome.”

On the face of it, it is difficult to see why the proper approach to treatment for dependence should take not just different, but exactly opposite forms in the employed compared with the unemployed.

NOFAS UK

The National Organisation on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome – UK (established as a Registered British Charity in September 2003) is committed to helping individuals with Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD), their families and carers by promoting public awareness about the risks of alcohol consumption during pregnancy, with the aim of reducing the number of babies being born with FASD.

The organisation provides information to the general public, press and medical professionals and delivers the following services in the United Kingdom for families facing problems related to FASD:

Helpline – 08700 333 700 – open five days a week, Mon to Fri 10am-6pm to give advice, support and information to all callers concerned about Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder.

Support group meetings for individuals affected by Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, their families, carers and health professionals.

Playgroups for children supervised by professional carers with CRB checks.

Family Support Newsletter

Educational film, “A Child for Life”, about FASD, with a pack for schools, midwives, families and other bodies, to educate people about FASD and the risks of drinking alcohol during pregnancy. The film is now being incorporated in training programmes for midwives throughout the UK.

Training and CPD Accredited Conferences.

Chairing the FASD Advisory Panel of International FASD Experts.

Working with the media to educate the public.

Leaflets and educational resources.

NOFAS-UK is working with the Department of Health to initiate new FASD research and is also liaising with Lord Mitchell in the House of Lords to bring the issue of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders to the attention of the British Government.

The Phoney War on Drugs – Kathy Gyngell

The Government has repeatedly declared that it is fighting a War on Drugs. But in a new report Kathy Gyngell of the Centre for Policy Studies argues that this has been a Phoney War.

Gyngell claims that the UK now has one of the most liberal drug policies in Europe. Both Sweden and the Netherlands (despite popular misconceptions) have, she says, a more rigorous approach – and far fewer problems with drugs. In contrast, the UK faces a widening and a deepening crisis. Over the last 10 years, Class A consumption and ‘problem drug use’ have risen dramatically, drug use has spread to rural areas and the age of children’s initiation into drugs has dropped. 41% of 15 year olds, and 11% of 11 year olds, have taken drugs. Drug death rates continue to rise and are far higher than the European average. The UK has 47.5 deaths per million population (aged 15 to 64) compared to 22.0 in Sweden and 9.6 in the Netherlands. There are over ten Problem Drug Users (PDUs) per 1,000 of the adult population, compared to 4.5 in Sweden or 3.2 in the Netherlands. Gyngell shows how the Labour Government has taken a new direction for drug policy. Its new “harm reduction” strategy aimed to reduce the cost of problem drug use (PDU). The focus was switched from combating all illicit drug use to the problems of PDU. Cannabis was declassified. Spending on methadone treatment increased threefold between 2003 and 2008. The aim of treatment for drug offenders was no longer abstinence but management of their addiction with the aim of reducing their reoffending. In practice, this meant prescribing methadone.

But, argues Gyngell, this harm-reduction approach has failed. It has entrapped 147,000 people in state sponsored (mainly methadone) addiction. The numbers emerging from government treatment programmes are at the same level as if there had been no treatment programme at all.

Weak enforcement and prevention

The UK drugs market is estimated to be worth £5 billion a year. In comparison, the Government is spending only £380 million a year – or 28% of the total drugs budget – attempting to control the supply of drugs (over £800 million is spent on treatment programmes and reducing drug-related crime). Only five boats now patrol the UK’s 7,750 mile coastline.

The numbers of recorded offences for importing, supply and possession of illicit drugs have all fallen over the last 10 years. At the same time, seizures of drugs have fallen and drug prices have dropped to a record low. The quantity of heroin, cocaine and cannabis that has been seized coming into the UK has fallen by 68%, 16% and 34% respectively (the recent announcement by SOCA of record cocaine seizures should be treated with great caution).

Both Sweden and the Netherlands have far more coherent and effective drugs policies. These are based on the enforcement of the drug laws (unlike in the UK, the majority of the drugs budget in both countries is spent on prevention and enforcement); the prevention of all illicit drug use; and the provision of addiction care.

Gyngell complains that these principles have been lost sight of over the last 10 years in the UK. A successful UK drug policy would in contrast:

- focus on the illicit use of all drugs, not the harms caused by drug use abandon the harm reduction approach

- develop treatment support aimed at abstinence and rehabilitation

- include a far tougher, better-funded enforcement programme to reduce the supply of drugs.

Alcohol in Britain – young men are binge-drinking less, but women are binge-drinking more

Alcohol in Britain – young men are binge-drinking less, but women are binge-drinking more

Research led by Dr Lesley Smith from Oxford Brookes University for

the Joseph Rowntree Foundation shows that the proportion of women who

binge-drink increased between 1998 and 2006 and is now at 15%.

However, the proportion of 16- to 24-year-old men

binge-drinking decreased by 9% since 2000, to 30% in 2006. Researchers

also found that whilst fewer children are drinking, those that do drink

are drinking much more than they did in the past. The researchers looked

at existing evidence on drinking trends in the general population over

the last 20 to 30 years. Five trends highlighted are:

- An increase in drinking amongst women

- An increase in drinking among middle-age and older groups

- A recent decrease in drinking among 16-24 year-olds (both sexes but especially men)

- An increase in alcohol consumption amongst children

- An increase in drinking in Northern Ireland compared with the rest of the UK

Researchers found excessive weekly drinking has increased in Northern Ireland compared with Great Britain as a whole. One possible explanation for this is the change in licensing laws in 1996, and the rapid growth in the leisure industry since the peace process began.

Dr Smith commented:

“Much concern has been expressed in recent years about young people’s drinking – and young people binge drinking in particular. Many people will be surprised to learn that young men’s drinking, including binge drinking, has gone down in recent years, while middle age and older people’s drinking has increased.”

The full report and Findings: Drinking in the UK: An exploration of trends by Lesley Smith and David Foxcroft from Oxford Brookes University, is available for free download from: www.jrf.org.uk

Nightlife and Crime – Social order and governance in international perspective

by Phil Hadfield Reviewed by Geoff Munro

Dr Hadfield has followed Bar Wars, in which he described “the night time economy [as posing] the greatest threat to public order in Britain today,” with an international review of associations between nightlife and criminal disorder, the role of the state, and governance of public space.

The structure of Nightlife and Crime testifies to Hadfield’s belief that the comparative study requires a close understanding of local conditions, “from the bottom up,” before any higher order interpretations are possible. Three dozen prominent and promising researchers explore the social contexts and regulatory environments of nightlife and criminal disorder in seventeen countries on four continents. Eighteen chapters comprise a worldwide survey, focused predominantly on English speaking countries including Hong Kong, plus The Netherlands, Norway and Finland, a Mediterranean bloc of Greece, Italy and Spain, and Hungary from the former Soviet bloc.

One of the sub-themes of this book is the struggle over the responsibility and role of the state in controlling the availability of and access to alcohol, and the circumstances in which it is consumed. As I was reading it the new Chief Police Commissioner in Victoria, Australia, denounced the state’s licensing rules for allowing “any idiot [to] get a liquor licence”. Yet, as Tanya Chikritzhs describes in her chapter on Australia, the dismantling over two decades of Victoria’s once formidably restrictive liquor licensing system, in order to achieve an open and competitive market for the sale of alcohol, has been used as a model by other Australian states keen to duplicate Melbourne’s “vibrant bar culture” and “24-hour city.” Significantly, Chikritzhs also points out that while the number of liquor outlets doubled in Victoria between 1991-and 2006, the rate of increase of alcohol attributable hospitalizations in Melbourne for the period 1999-2004 was double that of the rest of the country.

A similar loosening of alcohol controls in Norway, New Zealand, England, Wales and Scotland led to outcries over increased levels of risky drinking and violent crime, though there is not a necessary linear relationship because other variables are influential. Seymour and Mayock point out that Ireland’s ambivalent attitude to intoxication, higher disposable incomes, and more time expended by young people in venues there confrontation is likely, all exacerbate the risk of conflict. The authors of a chapter on South Africa perceive a “hegemonic masculinity”, which requires young males to act out an exaggerated version of manhood, as an important factor underlying high rates of nocturnal violence.

Another theme concerns how, as the state gives up its traditional powers, new forms of governance are called into being through the “privatisation of responsibility,” or arise through the non-government sector. Licensees are required to regulate themselves by, for example, acquiring private security agents, training bar staff in responsible service, joining voluntary licensing accords and adhering to other codes of practice. Meanwhile charities that provide outreach on nighttime economy streets to care for the intoxicated, sick or lost incidentally reduce street level crime, thereby forming a substitute police service.

Nevertheless demands for external controls on alcohol have not disappeared. After New Zealand expanded the class of businesses that sell alcohol and dropped the age at which people could purchase it, and experienced a rise in harmful drinking by young people, the government tried to reverse the age change. In Fiona Hutton’s summary: “…although policy makers have done all they can to encourage drinking they are now wringing their collective hands about the problems associated with increased alcohol consumption.”

Perhaps the same could be said of Scotland, which, having introduced the super-pub, increased off-licences, extended trading hours, and grown alarmed at the link between “…over consumption of alcohol and … crimes of violence,” is rethinking alcohol policy. This is one of the most intriguing chapters. Proposals to make public health an objective of licensing, to levy a social responsibility fee on liquor premises, to set a minimum price for alcohol and to limit purchase of packaged liquor to 21 year olds are being watched carefully in the Antipodes.

Apart from the analysis of the major themes, authors broach new drinking trends. These include an apparent polarisation wherein the proportion of abstainers and risky drinkers are both increasing within certain populations; the convergence of male and female drinking trajectories; the practice of preloading before visiting night time precincts, and the rise of “glassing” incidents in late night venues.

Nightlife and Crime is a most valuable work that breaks new ground and is sure to lead to further research and comparative studies in alcohol related violence, as well as other factors that contribute to heavy rates of night time offending.

Nightlife and Crime, published by Oxford University Press on 5 March 2009, is available from Amazon for £50.

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

Gambling industry harms and parallels with the alcohol world

Will Prochaska –

Coalition to End Gambling Ads