In this month’s alert

Responsibility deal under renewed pressure

Alcohol and health bodies criticise Diageo for funding programme warning of dangers of alcohol in pregnancy as part of the Deal, while Health Secretary suggests supermarkets might do more to help

Health Secretary, Andrew Lansley, has written to the leading supermarket companies, suggesting that they could do more to reduce aggressive alcohol marketing in their stores. The clear implication is that they are failing to take the Government’s Responsibility Deal seriously enough. At the same time, the alcohol and health organisations that decided to boycott the Responsibility Deal because of alcohol industry involvement, criticised Diageo for agreeing to fund an educational programme for midwives on the dangers of alcohol during pregnancy.

The Responsibility Deal is the name given to the Coalition government’s attempt to bring together the various industries whose products are relevant to health issues such as alcohol, obesity and physical fitness, with the health organisations. The idea is to persuade the commercial operators to sign up to the process of improving public health by doing useful things such as improved labelling of food and drink products. In pursuing this policy, the present government is, in fact, continuing an initiative begun under the previous Labour government, when it was known as the ‘Coalition for Better Health’. However, a number of alcohol and health bodies, including the Institute of Alcohol Studies and the BMA, decided to boycott the Responsibility Deal because they thought it gave the alcohol industry too much influence and was a diversion from ‘evidence-based’ alcohol policy (See Alcohol Alert Issue 1 Spring 2011)

Row over Diageo funding of alcohol and pregnancy programme

Controversy was caused by the announcement that Diageo had agreed to extend the funding of an education and training programme for midwives on the dangers of drinking alcohol during pregnancy. The training programme is being run by the National Organisation for Foetal Alcohol Syndrome UK (Nofas-UK), the leading health charity in the UK that focuses on the issue. Susan Fleisher, the Chief Executive of the charity, said the programme would have huge benefits.

“The thing that’s so fantastic is that they’re helping us with prevention, we can actually prevent children being born with foetal alcohol brain damage”, she said. “But it costs money, and thanks to Diageo we expect we will be educating, in the next three years, 10,000 midwives. Ultimately, if it all goes well, we will reach at least a million women.”

Anne Milton, the Public Health Minister, supported the initiative. She said: “Midwives are one of the most trusted sources of information and advice for pregnant women. This pledge is a great example of how business can work with NHS staff to provide women with valuable information.”

However, Vivienne Nathanson from the British Medical Association said that there were concerns over the scheme and its funding by Diageo. She said:

“They certainly have a conflict of interest because it’s in the interest of the drinks industry for people to continue to drink and it’s in the interest of health for people to drink much less, and certainly not to drink during pregnancy, or to drink really minimally. I think the issue for us would be if money is given by the industry, it must be given to an honest broker, a third party.”

Other alcohol and health bodies joined Labour Party health spokesmen in opposing the plan, labeling it a ‘smokescreen’ and accusing the Conservatives of allowing corporations “further influence on public health policy.”

However, speaking to Alcohol Alert, Susan Fleisher explained that Diageo began funding the pilot training programme two years ago, which means it began under the Labour government. The pilot was regarded as a success, and all that has now happened is that Diageo has agreed to fund the programme for a further three years. The programme promotes Nofas-UK’s standard advice on alcohol and pregnancy, which is based on the official guidance from the Department of Health. This is that, ideally, women who are pregnant or contemplating becoming pregnant should not drink alcohol at all, but if they do they should restrict consumption to a minimum. The programme was reviewed by the Royal College of Midwives, and the International FASD Medical Advisory Panel.

Ms Fleisher also confirmed that Diageo have no influence over the content of the training programme, and that Diageo’s logo does not appear on the published material.

Criticism by the alcohol and health organisations

Commenting on the Nofas- UK programme, Don Shenker, Chief Executive of Alcohol Concern, one of the organisations boycotting the Responsibility Deal, said: “It is deeply worrying that alcohol education is being paid for by the drinks industry, as it is then unaccountable and not necessarily based on evidence or public health guidance.”

Labour’s health spokesperson John Healey said: “Industry sponsored initiatives should not be an excuse for stealth cuts to funding for public health campaigns.”

Professor Ian Gilmore, Chairman of the Alcohol Health Alliance UK, of which Nofas-UK was one of the founder organisations, none the less branded the initiative a ‘diversion’ and said, “To really make a difference, education and information must be backed-up by tougher action on the price, availability and marketing of alcohol.”

For the IAS, Katherine Brown said:

“It is unnerving to see money being accepted from the drinks industry to fund alcohol education programmes when there is a direct conflict of interest between its profits and public health objectives.

“In funding this initiative, Diageo may be seen as a ‘responsible’ producer but we must also be reminded that the organisation is an influential and active opponent of effective alcohol policies such as minimum pricing, licensing restrictions and raising the drink drive limit.

“Foetal Alcohol Syndrome Disorder is an emotive subject, but so is domestic violence, sexual assault, homicide, homelessness, people dying from liver disease… all of which are exacerbated by the increased affordability and availability of alcohol.

“Evidence shows that this type of targeted activity is not an effective means of reducing levels of alcohol harm unless it is backed up by population-wide measures that tackle price, availability and promotion of alcohol.

“This PR initiative can be seen as a cynical distraction from the huge drink problem this country faces at present, and a worrying sign that government is hand in glove with industry.”

Supermarkets failing the Responsibility test?

It now seems that Health Secretary, Andrew Lansley, may himself have started to become impatient with the progress of the Deal in regard to sections of the alcohol retail sector. Mr Lansley has written to Tesco, Sainsbury’s, M&S, Morrisons, The Co-operative Group, Waitrose and Aldi, calling on them to do more to back the Deal, which was launched in March. The one exception was Asda, which, shortly after the strategy was announced, revealed it was removing front of store alcohol displays in its stores.

Interestingly, the letter was reported in the trade press as being a stiff rebuke to the recipients for not doing more. While the actual text of the letter reads more like friendly encouragement, (see full text) the implication between the lines is that the supermarkets are failing to do enough, quickly enough. This impression was confirmed by the briefings given to the media. The Department of Health told The Grocer magazine there was “increasing frustration from ministers” that major retailers had failed to take sufficient voluntary action on the back of its strategy to tackle obesity and alcohol abuse. Speaking to The Grocer, a spokeswoman at the Department of Health said that there was “increasing frustration from ministers that other supermarkets aren’t getting on board with similar pledges. I’d imagine Asda is not all that happy about being the lone commercial ranger either”.

She said Mr Lansley would also be writing to Asda “thanking them for their efforts”.

A spokesman for Asda said: “In April we made a decision that we would take the lead because we thought it was the right thing to do. For us it was the next step in a package of measures we began a couple of years ago when we began looking at one or two issues around the way alcohol was sold and displayed. We will stay close to the Government on this issue”.

The British Retail Consortium said it was perplexed by the Government’s attack.

A spokesman said: “This is a surprise. All the major retailers are actively pursuing the pledges they agreed with the Government in the Public Health Responsibility Deal. They deserve credit for providing customers with unit labelling, preventing underage sales of alcohol and funding the Drinkaware campaign exactly as they said they would”.

For the IAS, Katherine Brown took a different view. She said: “This latest stage of the Responsibility Deal debacle comes as no surprise and is exactly why we refused to sign up in the fi rst place. Relying on industry to adhere to voluntary pledges that could threaten their bottom line is never going to work. The Government knows this; it has commissioned reports that show the failings of self-regulation and seen evidence from the Health Select Committee.

“Tackling cheap booze in supermarkets should be a key priority for this Government if it is serious about reducing alcohol harm. This can only be achieved through increased regulation that demands industry compliance; voluntary agreements are not the answer to the nation’s alcohol problem.

“We don’t have time to waste saying ‘I told you so’, we need the Government to act now and produce a robust national alcohol strategy based on evidence of what works.”

Conservative MP introduces Bill to restrict alcohol marketing

Conservative MP, Dr Sarah Wollaston, has introduced a Ten Minute Rule Bill in the House of Commons to toughen regulations on alcohol advertising, along the lines of the French Loi Evin. Here, she explains the Bill.

Since arriving in Parliament, I have been campaigning for an end to our binge drinking culture and I introduced a Private Member’s Bill at the end of March to prevent alcohol being marketed to children.

About 13 young people will die this week as a result of alcohol, and about 650 this year. Nearly a quarter of all deaths of young people aged between 15 and 24 are caused by alcohol. That is two every day – far more than are killed by knife crime or cancer – yet this tragic loss from alcohol attracts far less by way of a response. These totally avoidable deaths are just the tip of the iceberg and do not begin to represent the full scale of the harm caused by alcohol to children.

Alcohol blights lives, with criminal records as a result of violent and antisocial behaviour, and it results in educational failure. Regretted and unprotected sex raises the risk of unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections. Around 7,500 children are admitted every year to English hospitals alone as a result of acute intoxication, and that figure does not include the carnage in our accident and emergency departments. There are many contributing factors and no simple solutions. Ultra-cheap alcohol and saturation availability still need to be tackled, but we also need a change in our drinking culture. The Bill aims to tackle one of the root causes of that culture, and there is a clear evidence base to support it. Youth culture is heavily influenced by marketing and our children are saturated by alcohol advertising. Despite the clear evidence of harm – only Denmark and the Isle of Man have higher levels of binge drinking and drunkenness in their schoolchildren – the European school survey demonstrated that our children have the most positive expectations of alcohol of any children in Europe and were the least likely to feel that it might cause them harm.

The problem of advertising

Where do those positive expectations come from? Let us just look at the scale of marketing in the UK. The estimated spend on alcohol marketing is around £800 million, compared with the Drinkaware Trust’s funding by the industry of just £2.6 million. When £307 is spent encouraging drinking for every pound spent promoting sensible behaviour, the results are predictable. The World Health Organisation hit the nail on the head when it said:

“In such a profoundly pro-drinking environment, health education becomes futile.”

The Portman Group, one of the main regulators of the industry, would have us believe that it runs a very tight ship and is effective in protecting children. That simply is not true.

Our confusing and inadequate combination of legislation and industry self-regulation is not working. The report on alcohol by the last Health Committee highlighted the fact that 96% of 13-year-olds from a sample of 920 were aware of alcohol advertising in at least five different media, and between 91% and 95% were able to identify masked brands. Nearly half owned alcohol-branded products, such as clothing. Does that matter?

A systematic review of multiple studies looking at the impact of alcohol advertising and media exposure on adolescents – a study that reviewed many studies – concluded that increasing exposure to alcohol marketing encourages children to start drinking younger and to drink more when they do. The Academy of Medical Sciences’ report “Calling Time” showed a consistent correlation between consumption levels by 11 to 15-year-olds and the amount spent on marketing. We can be sure that, if alcohol advertising did not work, the industry would not pay for it. So many of the possible solutions to our binge drinking epidemic are incompatible with European law, so it is rather refreshing to hear that France has found a way forward. In 1991, in response to saturation inappropriate marketing, the French introduced a measure called the Loi Evin. This law has been repeatedly challenged in the European courts and has been upheld as “proportionate, effective and consistent with the Treaty of Rome”, which all Members of Parliament would agree makes a pleasant change.

The French Model

Alcohol was a serious problem in France. In 1960 the French were consuming over 30 litres of pure alcohol per capita per year. Consumption is well under half that figure now. I accept that French levels of alcohol consumption were falling before the Loi Evin was introduced, but the French have managed to sustain that decline and the long-term trend continues to be downwards. That is partly because their young people are no longer exposed to a continuous barrage of insinuating and pervasive messages about alcohol.

I am not suggesting a retreat to the nanny state or a ban, but we should aim to protect children, especially as there is clear evidence of their exposure to marketing and the consequent harm. We currently have an absurd situation where advertisers are not supposed to link drinking with social or sexual success or portray drinkers as youthful or vigorous, but they can regularly sponsor major sporting and youth events, such as T in the Park. The Bill aims to reduce the exposure of children to the harmful effects of alcohol marketing by setting out what advertisers are allowed to say and where they can say it. Rather than the current confused cocktail of legislation and self-regulatory codes, let us switch to something that works.

The Bill would permit the promotion of alcohol in media that adults use. That would include the print media, where at least 90% of readers are adults rather than children, radio after 9 pm and films with an 18 certificate. It would allow advertising at the point of sale in licensed premises and at traditional producer events, so it would not penalise, for example, west country cider makers or small Scottish distilleries. In these media, advertisers would be permitted only to make factual and verifiable statements about their products, such as alcoholic strength, composition and place of origin. Every advert would also carry an advisory message about responsible drinking or health.

Any other marketing or promotion not specifically permitted would therefore be banned, and this would include television, social media and youth-certified films. The Bill would specifically prevent the growing threat from viral phone marketing and ploys such as “advergames” on the internet, where so-called games are a cover for alcohol marketing. I think we would all agree that those are designed specifically to appeal to young people. Ofcom, in its own research, has demonstrated that for every five 24-year-olds who see an alcohol advert on television, there are four 10-year-olds who see the same advert. The industry will claim that these measures will kill off sport and culture, and that advertising is designed only to persuade people to switch brands. The same claim was made before the tobacco advertising ban. I point out that France has managed a World cup and a European cup without any help from alcohol sponsorship.

Across the channel, the Loi Evin is backed up by heavy penalties which have been imposed by the courts and now act as a significant deterrent. May I ask that we stop putting the fox in charge of the chickens and have a clear statutory code to protect our children? The Government could adopt this measure very quickly.

The Coalition has staked a great deal on talking about outcomes. If we are serious about outcomes such as reducing health inequality, reducing violent crime and domestic violence, improving the life chances of our children and reducing teenage pregnancy, we must stop talking to the drinks industry, with its vested interest in increasing drinking, and start listening to those with real expertise in preventing alcohol-related deaths. Not so much big society, perhaps, as big sobriety.

Liverpool launches major bid to tackle alcohol harm

Liverpool has unveiled a three-year approach to preventing and reducing alcohol misuse. The city has the highest rates of alcohol-related hospital admissions in England, and its residents are twice as likely to die from an alcohol specific condition, such as liver disease, as the national average.

‘Reducing Harm, Improving Care’ has been produced by the Liverpool Alcohol Strategy Group, which is jointly chaired by Liverpool Primary Care Trust (PCT) and Liverpool City Council and includes other key agencies in the city.

The strategy sets out plans to double the number of individuals able to access alcohol treatment services, allowing an extra 2,000 people a year to receive help for their drinking. This will involve creating a new Community Alcohol Service, which will provide drop-in clinics between Monday and Friday in each of Liverpool’s five neighbourhood areas. Other initiatives include equipping the city’s frontline NHS workers – such as GPs, nurses and pharmacists – with the skills to identify harmful drinking in patients who may report to them with other symptoms. More than 350 staff have already been trained to identify those individuals who regularly consume alcohol above recommended levels, and offer them practical advice about cutting down. This is part of a wider approach to reach people who often don’t see their drinking as a problem, but who are unknowingly putting themselves at risk of diseases such as cancer, cirrhosis and high blood pressure. It is now estimated that by drinking over the daily recommended limits more than 42% of adult drinkers in Liverpool could fall into this category.

Dr Paula Grey, Director of Public Health for Liverpool, said: “Alcohol contributes to some serious health and social problems in Liverpool – as it does in many other cities – and tackling these issues presents a major challenge. It’s really important that key local agencies, such as the NHS, the local authority and the police, continue to work in partnership to address both the causes and impacts of alcohol misuse. We also need to ensure that the wider population understands what it means to drink at harmful levels. Many of those who exceed recommended daily guidelines associate alcohol misuse with teenage binge drinkers, and do not realise that their own behaviour is putting their health at risk. Part of our challenge is to make sure that people realise what they are consuming and what the effects could be, so that they can make informed decisions.”

In 2010, Liverpool PCT launched a campaign called ‘What’s Yours?’ to raise awareness about recommended daily guidelines for alcohol. It was particularly targeted at drinkers aged between 35 and 55, who might underestimate how many units they are drinking.

Future plans for the What’s Yours? brand include a dedicated website.

Professor Sir Ian Gilmore, liver specialist at the Royal Liverpool Hospital and former President of the Royal College of Physicians, said: “It’s welcoming to see local partnerships taking the initiative by introducing credible interventions to tackle alcohol-related harms and to continue to lobby for more strident national measures to protect the public, like a minimum unit price for alcohol and better control over its availability.”

Alcohol-related hospital admissions top 1 million, new report shows

The number of admissions to hospital in England related to alcohol has topped 1 million, according to the NHS Information Centre’s annual report, Statistics on Alcohol: England 2011.

Statistics show there were 1,057,000 such admissions in 2009/10. This is up 12% on the 2008/09 figure (945,500) and more than twice as many as in 2002/03 (510,800).

Of these admissions, nearly two thirds (63%) were for men. Among all adults there were more admissions in the older age groups than in the younger age groups.

New prescriptions data shows that alcohol dependency cost the NHS £2.41million in prescription items in 2010. This is up 1.4% on the 2009 figure (£2.38 million) and up 40% since 2003 (£1.72 million).

There were 160,181 prescription items prescribed for drugs to treat alcohol dependency in primary care settings or NHS hospitals and dispensed in the community in 2010. This is an increase of 6% on 2009 (150,445) and an increase of 56% since 2003 (102,741).

The report also shows that in 2010 in England:

There were 290 prescription items issued for alcohol dependency per 100,000 of the population

Regionally, the figures for prescription items per 100,000 of the population were highest in the North West (515 items) and North East (410 items) and lowest in London (130 items)

The NHS Information Centre Chief Executive, Tim Straughan, said: “Today’s report shows the number of admissions to hospital each year for alcohol-related problems has topped 1 million for the first time. The report also highlights the increasing cost of alcohol dependency to the NHS as the number of prescription items dispensed continues to rise.

“This report provides health professionals and policy makers with a useful picture of the health issues relating to alcohol use and misuse. It also highlights the importance of policy makers and health professionals in recognising and tackling alcohol misuse, which, in turn, could lead to Alcohol affordability index: 1980 (=100%) to 2010 savings for the NHS.” Responding to the publication of the report, Public Health Minister, Anne Milton, said:

“These statistics show that the old ways of tackling public health problems have not always yielded the necessary improvements. We are already taking action to tackle problem drinking, including plans to stop supermarkets selling below-cost alcohol and working to introduce a tougher licensing regime.

“We are taking a bold new approach to public health. Our recent white paper set out our plan to ring-fence public health spending and give power to local communities to improve the health of local people. We will also be publishing a new alcohol strategy later this year to follow on from the Public Health White Paper.”

However, some commentators noted the strangeness of alcohol-related hospital admissions appearing to increase sharply at a time when alcohol consumption is falling. According to the data presented in the report, the proportion of men drinking more than 21 units a week fell by two percentage points, from 28 to 26%, and the number of women drinking more than 14 units by one percentage point, from 19 to 18%, between 2008 and 2009. The commentators suggested that, in reality, the apparent increase in admissions is probably due to the change in the method of counting alcohol-related hospital admissions that took place in 2009.

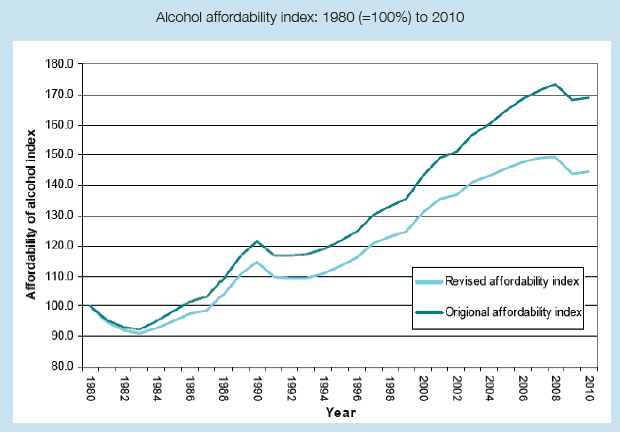

Alcohol Affordability

It is now generally accepted that alcohol affordability – how cheap or expensive alcohol is relative to disposable income – is one of the main factors explaining fluctuations in the level of alcohol consumption.

As a result of representations by the Institute of Alcohol Studies, National Statistics has now altered its method of calculating alcohol affordability. Previously, the affordability index was calculated partly on the basis of changes in the total disposable income of all households. Dr Rachel Seabrook of IAS pointed out that this was an unsatisfactory measure because changes in total household income reflected, in part, changes in the size of the population, and the measure was not, therefore, an accurate method of calculating the disposable income of individual consumers.

The new measure of alcohol affordability adjusts for this failing and thus provides a more accurate picture of the relationship between affordability and consumption. As can be seen from the graph (below), the old measure had the effect of exaggerating how affordable alcohol has become in recent years. However, even with the new, more accurate measure, alcohol in 2010 was still 44% cheaper than it was in 1980, highlighting the overall trend of increased affordability over the period.

Key Findings

In England, in 2009:

- 69% of men and 55% of women (aged 16 and over) reported drinking an alcoholic drink on at least one day in the week prior to interview. 10% of men and 6% of women reported drinking on every day in the previous week.

- 37% of men drank over 4 units on at least one day in the week prior to interview and 29% of women drank more than 3 units on at least one day in the week prior to interview. 20% of men reported drinking over 8 units and 13% of women reported drinking over 6 units on at least one day in the week prior to interview.

- The average weekly alcohol consumption was 16.4 units for men and 8.0 units for women.

- 26% of men reported drinking more than 21 units in an average week. For women, 18% reported drinking more than 14 units in an average week.

- In 2007, 33% of men and 16% of women (24% of adults) were classified as hazardous drinkers

- Among adults aged 16 to 74, 9% of men and 4% of women showed some signs of alcohol dependence

- 18% of secondary school pupils aged 11 to 15 reported drinking alcohol in the week prior to interview, compared with 26% in 2001

- Around half of pupils had ever had an alcoholic drink (51%), compared with 61% in 2003

- The overall volume of alcoholic drinks purchased for consumption outside the home has decreased by 39% from 733 millilitres (ml) of alcohol per person per week in 2001/02 to 446 ml per person per week in 2009. This reduction is mainly due to a 45% decrease in the volume of beer purchases from 623 ml to 342 ml per person per week over the same period.

- There has been an increase from 54% in 1997 to 75% in 2009 in the percentage of people who had heard of daily drinking limits

- In 2009, there were 6,584 deaths directly related to alcohol, a 3% decrease on the 2008 figure. Of these alcohol-related deaths, the majority (4,154) died from alcoholic liver disease.

- It is estimated that the cost of alcohol-related harm to the NHS in England is £2.7 billion in 2006/07 prices

The full report can be viewed at www.ic.nhs.uk/pubs/alcohol11

5500 GP alcohol consultations per day in Scotland

According to a survey conducted by the BMA in Scotland, on one day in April, alcohol was a factor in more than 5,500 consultations in general practice. This equates to around 1.4 million consultations per year, costing the NHS in excess of £28 million, and accounts for six per cent of all GP consultations.

The results of the BMA study are based on a sample of 31 practices (3% of the total number of practices) from across Scotland. These practices reported that, on the 21st of April 2011, 169 consultations with a GP or practice nurse had alcohol as a factor.

However, critics attacked the survey as unreliable, given especially the extremely small percentage of GP practices who responded and the absence of any attempt to ensure that they were properly representative of Scotland as a whole. One critic, Nigel Hawkes of the Straight Statistics website, accused the BMA of being a serial offender in publishing ‘dodgy surveys’.

Election Call

The survey results were released prior to the Scottish Parliament General Election, and BMA Scotland called on candidates in all the political parties to acknowledge the damaging influence of alcohol misuse on individuals and in communities every day in Scotland and to spend one of the last few days of the election campaign outlining how they will tackle alcohol misuse in the next Scottish Parliament.

The BMA summed up the position:

In one day:

- alcohol will cost Scotland £97.5 million in terms of health, violence and crime

- alcohol will kill five people

- 98 people will be admitted to hospital with an alcohol-related condition

- 23 people will commit a drink driving offence

- 450 victims of violent crime will perceive their assailant to be under the influence of alcohol

Dr Alan McDevitt, Deputy Chairman of the BMA’s Scottish General Practitioners’ Committee, said:

“We wanted to conduct this survey to demonstrate very clearly how much of an impact alcohol has on the everyday work of general practice. Those who suffer from alcohol-related health problems are not just alcoholics or heavy binge drinkers. By regularly drinking over and above recommended limits, a significant proportion of the adult population is at risk of experiencing health problems that are linked to the alcohol they consume, whether it is high blood pressure, breast cancer or even domestic abuse.

“In just one day, nurses and doctors working in general practices across Scotland saw more than 5,500 patients where alcohol had contributed to their ill health. But the patients seen in general practice are just the tip of the iceberg. The impact of alcohol misuse across the rest of the NHS, in hospitals and in our communities is far greater.

“That is why we are asking the parliamentary candidates to spend one day talking about how they are going to address this serious issue in the next Scottish Parliament. I think this is the very least that they can do for their constituencies.”

Theresa Fyffe, Chief Executive of the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) Scotland, said:

“We now need to hear from politicians of all parties about what they are going to do to reduce the harmful effects of alcohol. For instance, they could consider investing in more alcohol liaison nurses who provide a whole range of support that ultimately saves the NHS money by reducing re-attendance at A & E and hospital admissions. It is time for the political parties to set out exactly what they intend to do to help stem the tide of harm caused by alcohol across Scotland.”

Evelyn Gillan, Chief Executive of Alcohol Focus Scotland, said:

“We must face up to the fact that the increase in alcohol consumption is being fuelled by the fact that alcohol is more affordable, more available and more heavily marketed than at any time over the last thirty years. The cheaper it is the more we consume. For the health and well-being of everyone in Scotland robust action must be taken to increase price. As we approach the Scottish elections on 5 May, we would urge politicians from all parties to reflect on the worrying levels of alcohol-related harm which individuals, families and communities are experiencing and to consider again the urgent need for a minimum unit price for alcohol to reduce the devastating effects of excessive drinking fuelled by cheap booze.”

Dr Bruce Ritson, Chairman of Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems (SHAAP) said:

“The level of harm caused by alcohol in Scotland concerns not only health workers, but other professions, individuals, families and communities across the country. All will be looking to the next Scottish Parliament for effective action to reduce problem alcohol use. Enforcement of existing legislation is one approach, but politicians will need to recognise that most people seen in general practice with an alcohol-related condition have not broken any law. The simple fact is that individually and collectively we are drinking at levels that compromise our health and well-being and, as a society, we need to drink less.”

However, Nigel Hawkes and Straight Statistics remained unconvinced. They complained that, as well as the failure to ensure the representativeness of the respondents to the survey, the BMA had also neglected to standardise the criteria for defining a consultation as ‘alcohol related’, making it difficult or impossible to interpret the results of the survey.

Alcohol death rate greater for women and men in routine jobs

Men whose jobs are classified as ‘routine’, such as van drivers and labourers, face 3.5 times the risk of dying from an alcohol-related disease than those in higher managerial and professional jobs.

Women in ‘routine’ jobs, such as cleaners and sewing machinists, face 5.7 times the chance of dying from an alcohol-related disease than women in higher professional jobs such as doctors and lawyers.

These are two of the conclusions contained in a new report published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). It is the first analysis of the social inequalities in adult alcohol-related mortality in England and Wales at the start of the 21st century as measured by the National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (NS-SEC).

The analysis highlighted the fact that the number of alcohol-related deaths in England and Wales doubled between 1991 and 2008, rising from 3,415 (6.4 per 100,000 population) in 1991 to 7,344 (12.4 per 100,000) in 2008. However, the most recent data in 2009 indicated a drop in alcohol-related deaths of 3.3%, to 7,099.

The focus of the current analysis was social inequality in alcohol-related mortality. Mortality rates from alcohol-related causes were consistently higher for men than women across all the NS-SEC analysis classes in England and Wales.

The highest mortality rate of all classes occurred in routine workers, for men at age 50-54, 52.2 per 100,000, and for women at age 45-49, 42.0 per 100,000.

For the less advantaged groups, alcohol-related mortality peaked in middle age and then declined, whereas for managers and professionals, the risk of mortality increased steadily with age. This means that alcohol-related deaths in the less advantaged groups tend to occur younger as well as being more common.

Region

The highest mortality rate for men in all occupied classes combined was found in the North West of England (26.9 per 100,000) followed by the North East (23.7), the West Midlands (23.6) and London (21.3). These regions all had significantly higher mortality rates for all occupied classes combined than England and Wales as a whole, where the figure was 19.0 per 100,000. The lowest mortality rate for all occupied classes combined occurred in the East of England (12.4 per 100,000), half of that seen in the North West. The second lowest was the South West (15.2) followed by the East Midlands and the South East, both 15.5 per 100,000. Similar regional patterns were observed for women, but with lower overall death rates.

Previous survey results have suggested that less advantaged social groups drink less in total than the more advantaged groups. Therefore the explanation for these inequalities is not a simple one, and may be associated with differences in the detailed patterns of drinking among different groups or with the influence of underlying factors other than alcohol consumption.

Alcohol-related deaths include only those causes defined as being most directly due to alcohol consumption, including alcoholic liver disease (accounting for approximately two-thirds of all alcohol-related deaths), fibrosis and cirrhosis of the liver, (accounting for about 18% of deaths), mental disorders due to the use of alcohol (about 9% of deaths) and accidental alcohol poisoning (about 3%). It does not include other diseases where alcohol has been shown to contribute to the risk of death, such as cancers of the mouth, oesophagus and liver. It also excludes deaths from accidents and violence where alcohol may have played a part.

Social inequalities in alcohol-related adult mortality by National Statistics Socio-economic Classification, England and Wales, 2001-03 – Statistical Bulletin

The article, which can be found in ‘Health Statistics Quarterly 50’ at http:// www.statistics.gov.uk/hsq, gives the first detailed breakdown of alcohol-related deaths by NS-SEC, age, gender and region and underlines the fact that people from less advantaged sections of society in England and Wales are disproportionately dying from alcohol-related causes at earlier ages.

Psychiatrists call for action to tackle substance misuse in older people – lower ‘sensible drinking limit’ recommended for pensioners

The NHS must wise up to the ‘growing problem’ of drug and alcohol misuse among older people, according to a new report published by the Royal College of Psychiatrists. The report, written by the Older People’s Substance Misuse Working Group of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, warns that not enough is being done to tackle substance misuse in our aging population – making them society’s ‘invisible addicts’. The report pulls together evidence to highlight the extent of the problem:

The number of older people in the UK population is increasing rapidly – between 2001 and 2031 there is predicted to be a 50% increase

A third of older people with alcohol use problems develop them in later life – often as a result of life changes such as retirement or bereavement, or feelings of boredom, loneliness and depression

Older people often show complex patterns and combinations of substance misuse e.g. excessive alcohol consumption as well as inappropriate use of prescribed and over the counter medications Although illegal drug use is uncommon among over-65s at the moment, there has been a significant increase in the over-40s in recent years. The problem is likely to get worse as these people get older.

Professor Ilana Crome, Professor of Addiction Psychiatry and Chair of the Working Group, said: “The traditional view is that alcohol misuse is uncommon in older people, and that the misuse of drugs is very rare. However, this is simply not true. A lack of awareness means that GPs and other healthcare professionals often overlook or discount the signs when someone has a problem. We hope this report highlights the scale of the problem, and that the multiple medical and social needs of this group of people are not ignored any longer.” The Working Group makes a series of key recommendations including:

- GPs screen every person over the age of 65 for substance misuse as part of a routine health check

- The government issues separate guidance on alcohol consumption for older people. Current recommended ‘safe limits’ are based on work in younger adults. Since there are physiological and metabolic changes associated with aging, these limits are too high for older people. Evidence suggests the upper ‘safe limit’ for older men is 1.5 units per day or 11 units per week, and for women 1 unit per day or 7 units per week.

- Public health campaigns around alcohol and drug misuse are developed specifically to target older people

- All doctors, nurses, psychologists, social care workers and allied health professionals are given suitable training in substance use disorders in older people

There is accumulating evidence that the treatment for alcohol and drug misuse in older people is effective and that older people often stay in treatment for longer than younger people. Dr Tony Rao, a consultant in old age psychiatry and member of the Working Group, said: “We are witnessing the birth of a burgeoning public health problem in a ‘baby boomer’ generation of older people for whom alcohol and drug misuse is growing. There is a pressing need to meet this need with primary, secondary and tertiary care services that can offer timely and effective detection, treatment and follow up for a large but hidden population.” Dr Owen Bowden-Jones, Chair of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Faculty of Addictions Psychiatry, said: “Because of the preconception that alcohol and drug use are problems of the young, there is a generation of older people for whom these problems have gone undetected. This timely report is a wake-up call for healthcare professionals and a reminder that older people have particular risks for substance misuse. Our challenge is to improve the detection of these invisible addicts and offer the treatments which we know can transform people’s lives.” Don Shenker, Chief Executive of Alcohol Concern, said: “While younger excessive drinkers often make the headlines, we should remember that older people often turn to alcohol in later life as a coping mechanism and this can remain stubbornly hidden from view. This report calls for much greater recognition that excessive drinking in older age is both widespread and preventable, particularly if public health professionals are supported and trained to spot the signs and take appropriate action.”

Alcohol blamed for high suicide rates in Northern Ireland

Alcohol and drugs are fuelling homicide and suicide rates in Northern Ireland, a new independent report by University of Manchester researchers has found, with alcohol appearing to be a key factor for the country’s higher suicide rates, including among mental health patients, compared to England and Wales.

The ‘Suicide and Homicide in Northern Ireland’ report by the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness (NCI), which is based in the University’s Centre for Suicide Prevention, also shows that the higher Northern Ireland suicide rate is greatest among young people; 332 suicides occurred in people under 25 during the study period (2000 to 2008), with mental illness, drugs and alcohol, previous self-harm and deprivation being contributing factors in the majority of cases.

The NCI report – commissioned by the Health and Social Care Division of the Public Health Agency (PHA) on behalf of the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (DHSSPS) in Northern Ireland – also reports: A total of 1,865 suicides occurred in the general population in Northern Ireland between 2000 and 2008, equivalent to 207 per year, or 13.9 per 100,000 people per annum. This rate is higher than the UK average but lower than the rate in Scotland.

During the same period, there were 533 suicides in current mental health patients – defined as individuals who had had contact with mental health services in the previous 12 months. This amounted to 29% of all suicides and corresponds to 59 patient deaths per year.

Young people who died by suicide were more likely than other age groups to be living in the poorest areas and they had the lowest rate of contact with mental health services (15%). Young mental health patients who died by suicide tended to have high rates of drug misuse (65%), alcohol misuse (70%) and previous self-harm (73%).

There were 142 homicide convictions between 2000 and 2008. This figure, while likely to be an underestimate, equates to 16 homicides per year, or 10.6 per million people per annum, similar to the rate in England and Wales but lower than the rate in Scotland.

“High rates of substance misuse and dependence run through this report and, as we rely on information known to clinicians, our figures are likely to underestimate the problem,” said Louis Appleby, Professor of Psychiatry at The University of Manchester and NCI Director.

“Alcohol misuse was a factor in 60% of patient suicides and this appears to have become more common during the course of the study period. Alcohol dependence was also the most common clinical diagnosis in patients convicted of homicide, with more than half known to have a problem prior to conviction.

“In homicide and suicide generally, alcohol misuse was a more common feature in Northern Ireland than in the other UK countries and a broad public health approach, including better dual diagnosis of mental illness and alcohol or drug misuse, health education and alcohol pricing, should be seen as key steps towards reducing the risk of both homicide and suicide. In particular, there needs to be a focus on developing new services for young people with substance misuse problems.”

The NCI report, which was launched at Mossley Hill, Newtownabbey, Northern Ireland, on Wednesday, June 29, also revealed that there was not a single ‘stranger homicide’ by a patient with mental illness throughout the eight-year study period.

“Stranger homicides are important in mental health because they are assumed to reinforce public prejudice against mentally ill people, the popular assumption being that the killing of a stranger is likely to be associated with mental illness,” said Professor Appleby, who is also National Director for Health and Criminal Justice. “

In this report, almost a third of homicides involved the killing of a stranger and the frequency of these cases appeared to have increased in the decade up to 2008. However, these were not associated with mental disorder and we recommend initiatives to combat the stigma of mental illness should emphasise the low risk to the general public from mentally ill patients living in the community.”

Controversy over welfare benefits for problem drinkers and drug addicts

Welfare benefits for people with alcohol or drug problems hit the headlines again when the Department of Work and Pensions released figures showing that, in 2010, 80,000 people dependent on either alcohol or other drugs were receiving incapacity benefit or what, since October 2008, has been known as Employment Support Allowance.

The figures showed that over 48,000 of the total had been in receipt of benefits in excess of 5 years, over 22,000 for ten years or more. Further doubt on the effectiveness and fairness of the present arrangements for paying welfare benefits was prompted by separate figures showing that three-quarters of people who apply for sickness benefit are found fit to work or drop their claims before they are completed. The figures show 887,300 of 1,175,700 people applying for employment and support allowance (ESA) between October 2008 and August 2010 failed to qualify. Only 6% of claims – 73,500 people – were considered to be entitled to full ESA support.

Employment Minister, Chris Grayling, said the figures showed how important it was to reassess people who were still on the old incapacity benefit.

“We now know very clearly that the vast majority of new claimants for sickness benefits are in fact able to return to work. That’s why we are turning our attention to existing claimants, who were simply abandoned on benefits. That’s why we are reassessing all of those claimants, and launching the work programme to provide specialist back to work support,” he said.

Alcohol and Drug Claimants

Prime Minister, David Cameron, promised tough action to reduce the numbers of people on ESA. Speaking to the BBC, he said that the public believed welfare recipients should be “people who are incapacitated through no fault of their own”. He continued: “Of course someone who has an alcohol or drug problem has a problem, but is it OK to leave these people on incapacity benefit, year after year, not examining their circumstances, not seeing if we can help them? It traps people in long-term poverty and it is not good enough.”

Mr Cameron said the government was showing courage to re-examine all existing incapacity benefit claims, suggesting recipients had been “left for dead” by the last government, and those not entitled to the payments would have them removed.

The Coalition Government is, in fact, continuing a process begun by the previous Labour Government of attempting to get people off incapacity benefit and back into work. Altogether, over 2 million people receive incapacity benefits, with over 900,000 being in receipt of benefits for 10 years or more. In relation to people with alcohol or drug problems, the position is the same as with other claimants in that their medical condition, in their case, dependence, does not, of itself, provide an entitlement to welfare benefits. Decisions on entitlement to benefits are based on claimants’ ability to carry out a range of tasks or on the effects of any associated mental health problems.

Alcohol awareness campaigners welcomed the aim of helping people to give up drink and get back to work but warned removing benefits from vulnerable people risked making their situation worse.

Don Shenker, Chief Executive of Alcohol Concern, said he was concerned the government was not prepared to commit enough funds to tackle a shortage of treatment facilities for those with addictions. He told the BBC:

“I would imagine that the vast majority would find it quite difficult to go back into the workplace because, first of all, how many employers would take on someone who’s been out of work for two or three years because they’ve been drinking?

“Secondly, the very stressful nature of being in the workplace environment means that for people who are heavily dependent on alcohol it would be difficult for some people to hold down a job.”

Martin Barnes, Chief Executive of DrugScope, said:

“Most people with a drug or alcohol dependency also have physical or mental health problems which can affect their ability to work. While a drug or alcohol dependency can be extremely debilitating, it does not, of itself, give an entitlement or ‘passport’ to benefit, which may be suggested by the publication of today’s figures. People with drug or alcohol problems must satisfy all the conditions for benefit entitlement, including proof of incapacity, and may be required to undergo a medical examination to determine eligibility.

“For many people with drug problems, employment can help support and sustain recovery from dependency. DrugScope supports the government’s commitment to help drug users into employment, as part of a broader recovery agenda. However, while people in drug treatment and recovery want to access training and employment, they can face formidable barriers, not least the stigma associated with drug or alcohol dependency. Research and experience shows that a majority of employers will not knowingly take on someone with a history of drug problems even if they are otherwise able to do the job.

“Despite the clear challenges of supporting people who have had drug or alcohol problems off benefit and into employment, it is unclear what specific, tailored support the government is providing, despite the clear ambition and commitment set out in the drug strategy. It has recently been confirmed that two support programmes for people with drug and alcohol problems are being discontinued, with no new referrals to the Progress to Work scheme after 1 June 2011 and no further funding for dedicated Job Centre drug coordinators. Both initiatives provided welcome and necessary tailored support for people with often multiple and complex problems associated with drug dependency. It is still unclear what specific support for this client group will be provided by the new Work Programme.

Employment Minister, Chris Grayling, said private and voluntary organisations had agreed to invest £580m in treating addicts and preparing them for employment, adding that all of the conditions were treatable if people received the right support.

Issue of legal liability raised by the case of the Irish barmen

The question of the legal liability of the owners of bars and the servers of alcohol in cases where harm arises from the consumption of the alcohol provided to customers, came into sharp focus in Ireland when two barmen were charged with manslaughter following the death of a customer from acute alcoholic poisoning.

In the context of the alcohol trade, issues of civil liability can arise in terms of a duty of care but there is also the possibility of criminal responsibility when a licensee or member of their staff could be regarded as aiding or abetting the commission of a criminal offence such as drink driving.

Inspired by the success of tobacco litigation, many alcohol policy advocates have favoured making licensees or their servants legally liable for the harmful consequences to themselves or others of their customers’ alcohol consumption, in circumstances where the licensees can be shown to have acted neglectfully or irresponsibly. In 2004, one of Scotland’s leading licensing specialists called for ‘server (or third-party) liability’ to be introduced to produce more responsible behaviour on the part of the country’s pubs and clubs.

Jack Cummins, one of Scotland’s foremost licensing experts, said: “It has yet to be established whether, under Scots law, a licensee owes a ‘duty of care’ to members of the public who may be affected by the acts of their intoxicated patrons. The day could well come when a court decides that allowing a customer to consume an excessive amount of alcohol, or worse still, encouraging excessive consumption, creates a foreseeable risk to third parties, rendering the licensee answerable in damages to victims of violence.” Others, however, have opposed the idea as leading to great injustice, promoting a harmful ‘compensation culture’ and as undermining the personal responsibility of the drinkers themselves.

The Irish Case

In the Irish case, the two barmen were put on trial following the death of a British customer, Graham Parrish, who died of acute alcoholic poisoning after celebrating his 26th birthday at a hotel in Thurles, Ireland in 2008. Among the drinks he had consumed was one containing multiple ‘shots’ in one glass which he downed in one go. The two defendants told the trial jury that they would have declined to serve this particular drink had they understood it was not going to be shared between Mr Parrish and his friends. The charge came under the common law heading of ‘involuntary manslaughter’, where the accused does not intend to harm the victim, but acted in such a negligent way it was foreseeable that harm would ensue.

The Irish Times reported that evidence was presented at the trial that Mr Parish had begun drinking at about 7pm with some friends and had drunk eight pints by 10pm when he and his friends began ‘to race their pints’. When he went to the toilet, his friends twice ordered vodkas to put in his pint.

Mr Parish drank both pints unaware they contained shots. Around 10.30pm, some of his friends ordered 10 shots in a pint glass and Mr Dalton, the barman on duty at the time, asked Mr Wright, his manager, if it was all right to put so much spirits in one glass. Wright told the Irish police that he agreed to serve the drink on the understanding that it would be shared and not downed in one go as it ultimately was, Mr Parrish being spurred on by his friends who bet on him to drink it.

Mr Parrish later fell off his stool and was left in an upstairs function room by his friends where he was checked on at about midnight and found to be snoring. But he was later discovered unconscious by a night porter at about 6am and pronounced dead at 7.15am. A post mortem revealed he had a blood alcohol level of 375mgs per 100mls, which proved fatal.

Legal liability and alcohol policy

The authors of the text book of alcohol policy, ‘Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity’, state that holding servers legally liable for the consequences of providing more alcohol to persons who are already intoxicated, or those underage, has shown consistent benefits as a policy measure in the US. In particular, States that hold bar owners and staff legally liable for damage attributable to intoxication have lower rates of traffic fatalities and homicide.

However, in Europe, there appear to be greater legal obstacles in the way of bringing successful prosecutions against licensees. While there do not seem to have been many cases brought before the courts, most of those that have been brought seem to have been lost, including that of the Irish barmen.

For example, in 2003 in Scotland, twelve problem drinkers made an attempt to sue drink manufacturers for failing to warn them of the dangers of alcohol. The group, aged between 18 and 60, claimed that drinking had led to ill health, loss of jobs and the breakdown of relationships, damaging their quality of life. They argued that the drink manufacturers owed them a duty of care to warn of the dangers of addiction. However, the case was not successful.

Irish Acquittal

In the Irish case, the judge directed the jury to acquit the defendants. He found that, while there was enough evidence of ‘gross negligence’ by the men to be brought to the jury, the fact that Parish had taken the decision to consume the alcohol broke the ‘chain of causation’ linking the barmen’s actions to his death.

The Irish Times, in an analysis of the case, commented that the barmen’s case followed another Irish High Court judgment which also emphasised the personal responsibility of the consumer, rather than that of the providers of the alcohol, for any injury that followed. In that High Court civil case which involved drink driving, Mr Justice Feeney reviewed the law in several common law jurisdictions about the responsibility of bar staff for the actions of those who consume alcohol on their premises. He said there was a wide divergence between Australia and the UK on the one hand, and Canada and the US on the other, in their attitudes towards the responsibilities of alcohol providers. He pointed out that this reflected the different historical and cultural contexts. Both the US and Canada had had years of prohibition, and this was reflected in their continuing approach to alcohol.

The Canadian courts had found that providers owed a broad duty of care to those consuming their alcohol, and US laws in most states held retail establishments accountable for harm, death or other damages caused by an intoxicated customer.

However, in Australia, the courts declined to impose alcohol-provider liability, and in the UK, while each case was fact-dependent, there was a clear reluctance to impose liability except in exceptional circumstances. He agreed with this approach, and found the bar staff in this instance did not owe a duty of care to the drink driver.

The Irish Times concluded that this judgment, combined with the acquittal of the barmen, means that, except in exceptional circumstances, criminal responsibility for death or injury arising from consuming large amounts of alcohol rests with the consumer, not the provider.

New guidance for treating alcohol dependence

The majority of people who are dependent on alcohol are not currently being treated, partly because health and social care professionals are failing to identify those in need and assisted withdrawal treatments are inadequate. In response, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has published new guidance outlining how the NHS should diagnose, assess and treat the condition.

Although over one million people in England are dependent on alcohol, only around 6% of these currently receive treatment. This means that every year there are over 940,000 people who are either not seeking help, do not have access to the relevant services, or whose symptoms are not being appropriately identified by healthcare professionals.

This is the first time that NICE has published guidance for the NHS to help address these serious variations in clinical practice. The guideline calls for all relevant health and social care professionals to be able to identify patients who could be misusing alcohol through clinical interviews and internationally recognised assessment tools, such as the AUDIT and SADQ. These will help healthcare professionals to make accurate diagnoses and measure the severity of their patients’ dependence, on which their subsequent treatment options will be based.

Dr Fergus Macbeth, Director of the Centre for Clinical Practice at NICE said: “People who suffer from alcohol dependence often face much stigma and discrimination in their day to day lives which can act as a barrier to them seeking help. Our guideline calls for all healthcare professionals who come into contact with these people to be appropriately trained to identify those in need and be able to offer them help in a trusting, supportive and non-judgemental environment. “Improvements must be made across the NHS so that more people can be correctly diagnosed, assessed and treated for their dependence and harmful drinking patterns. Our clinical guideline outlines the most effective ways that the NHS can do this, based on the available evidence and expert feedback.”

Alcohol dependence is characterised by a craving for, tolerance of, and preoccupation with alcohol and continued drinking, despite the physical and mental harm that it can cause.

Harmful drinking is defined as drinking over the recommended weekly amount and experiencing health problems directly related to alcohol. This could include psychological problems such as depression and anxiety, or physical illness such as high blood pressure, acute pancreatitis, liver cirrhosis, heart disease and several cancers.

Other key recommendations from NICE include:

- Harmful drinkers and people who are mildly dependent (e.g. those who score 15 or less on the SADQ) should be offered psychological interventions, such as cognitive behavioural therapy, behavioural couples therapy or social network and environment-based therapies.

- People who drink more than 15 units a day or who score 20 or more on the AUDIT should be offered a structured assisted withdrawal programme. This can be offered in a community-based setting, unless there are safety concerns; e.g. if the person drinks more than 30 units a day, scores more than 30 on the SADQ, has a history of epilepsy, withdrawal-related seizures, delirium tremens or previous withdrawal attempts, is homeless, or needs concurrent assisted withdrawal from benzodiazepines.

In these circumstances, people should be offered an inpatient or residential assisted withdrawal programme. People who drink 15-20 units of alcohol a day and have significant mental or physical problems (e.g. depression or psychosis) or a significant learning disability or cognitive impairment, should also be offered inpatient or residential assisted withdrawal.

After completing a successful alcohol withdrawal programme, healthcare professionals should consider offering people who were moderately or severely dependent, acamprosate or oral naltrexone. This should be offered alongside an individual psychological intervention which specifically focuses on alcohol misuse.

Health and social care professionals should seek to treat a person’s alcohol misuse before treating any coexisting mental health conditions, e.g. depression or anxiety. This is because symptoms can often improve once alcohol misuse has been effectively treated. However, if a person with a mental health condition hasn’t experienced significant improvements after abstaining from alcohol for around 3-4 weeks, then the health and social care professionals should consider referring them for specific treatment for this.

Professor Colin Drummond, Professor of Addiction Psychiatry and Chair of the Guideline Development Group said: “The clinical guideline from NICE has been developed following a detailed systematic review of research on the full range of alcohol treatments to date. The evidence shows that alcohol treatment can be both effective and cost effective. However the effectiveness of these are crucially dependent upon people who misuse alcohol having better access to evidence-based interventions, which are delivered by appropriately trained and skilled staff.

“With problems relating to alcohol consumption increasing steeply in the UK, I hope that this guideline provides a much needed impetus to making effective treatments more available to those who need them.”

Alcohol use disorders: diagnosis, assessment and management of harmful drinking and alcohol dependence. NICE 2011

National Treatment Agency issues guide to safeguarding children affected by substance misuse

A third of drug addicts or problem drinkers in treatment have childcare responsibilities and the lives of these children are much improved when providers and children’s services get together early on to ensure the whole family gets the support it may need.

A new practical guide issued by the National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse (NTA) says those responsible for drink and drug treatment must take a wider, more preventative approach, identifying early on when families need help as well as protecting children from neglect and harm.

The guide also calls on children and family services to view treatment for parents as a way of improving life for the whole family and to get involved when problems are first identified, ensuring these are dealt with before a crisis point is reached.

Rosanna O’Connor, Director of Delivery for the NTA, said:

“In many ways, having a parent in drug or alcohol treatment protects the child because their mother or father is more motivated to get better, stabilise their lives and seek support.

“The danger is, as the Munro Review pointed out, that children are too often ‘invisible’ to adult front line services, including those dealing with substance misuse, which tend to focus on the person in front of them.”

The guide draws on existing guidelines and makes new recommendations on how those seeking treatment are assessed and when and how children and families services should be involved. It offers clear advice to managers and commissioners on partnership working to identify, assess, refer, support and treat adults with the aim of protecting any children involved and improving their outcomes.

Supporting Information for the Development of Joint Local Protocols between Drug and Alcohol Partnerships, Children and Family Services was supported by the Department for Education and is available on the NTA website at www.nta.nhs.uk

New research ‘makes the case’ for investment in young people’s drug and alcohol treatment

A government commissioned evaluation has found that alcohol and drug treatment services for young people are highly cost effective, with long term savings of between £5 and £8 for every pound invested.

Published by the Department for Education, the report, ‘Specialist drug and alcohol services for young people – a cost benefit analysis’, finds that drug and alcohol treatment for young people reduces otherwise significant economic, social and health costs. Immediate savings are achieved in reduced crime and improved health. In the longer term, there are reductions in costs associated with problematic drug use in adulthood, including unemployment, crime and drug and alcohol dependency.

Approximately 24,000 young people received specialist drug and alcohol treatment in the UK in 2008/09. Most were treated primarily for alcohol (37%) or cannabis (53%); one in ten were treated for problems associated with Class A drugs, including heroin and crack.

Despite evidence of the cost effectiveness of spending on substance misuse treatment, many young people’s services have contacted agencies such as DrugScope to report significant cuts in local funding.

Commenting on the report, Martin Barnes, Chief Executive of DrugScope said: “At a time when many drug and alcohol services for young people are facing funding cuts, this research makes a timely, compelling and robust case for continued investment. Even on quite cautious and conservative estimates, the evidence shows that there are immediate net gains in return for spending on drug and alcohol treatment. Not only will cuts in services have a negative impact on vulnerable young people, the research confirms that greater costs are likely to be incurred in terms of crime, unemployment and poor health.

“The concern is that, with a record number of young people not in education, employment or training, there will be a greater demand on prevention and treatment services. It is far easier to prevent young people from developing problems at an early stage than it is to treat adults with addiction issues. A considered assessment of the benefits to local communities of investment in drug and alcohol treatment services needs to be made to inform decisions on funding.”

Dowload the full report (pdf 454kb)

Major survey shows family and friends are key influences on teenage drinking

A major survey of early teen drinking patterns in England finds that drinking escalates to a worrying extent during these years. The research, conducted by Ipsos MORI for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, also finds that family and friends have a strong influence on teenagers’ drinking patterns, and are stronger influences than some other factors – such as individual well-being, celebrity figures and the media.

The detailed survey of 5,700 teenagers looked at the drinking habits of students in years 9 (aged 13–14) and 11 (aged 15–16). The study found that around seven in ten students in year 9, and nine out of ten students in year 11, had drunk alcohol, the majority claiming to have had their first drink by the time they were 13. Around one in five students had been drunk multiple times by the time they reached 14; this number leapt to around half of students by age 16.

Pamela Bremner from Ipsos MORI, lead author of the report, said: “For the first time in the UK, this study ranks what most influences young people’s drinking behaviour. It found that the behaviour of friends and family is a strong influential factor in determining a young person’s relationship with alcohol.”

Teenagers’ friends have a significant impact on drinking behaviour. The odds of a teenager drinking to excess more than double if they spend more than two evenings a week with friends. Spending every evening with friends multiplies the odds of excessive drinking more than four times. Parents have a particularly strong impact on their children’s behaviour with alcohol. Levels of parental supervision influence behaviour: for example, the odds of a teenager having ever had an alcoholic drink are greater if their parents do not know where they are on a Saturday evening or if they allow their child to watch 18-rated films unsupervised.

Parents’ own drinking habits also have an impact. The odds of a teenager getting drunk multiple times is twice as great if they have seen their parents drunk, even if only a few times, as those teenagers who have never seen their parents drunk. Ease of access to alcohol was also an important influencing factor on current drinking and drunkenness.

However, researchers found mixed messages about the ideal age and method of introducing teenagers to alcohol. In general terms, those introduced to alcohol when very young had greater odds of having had a drink recently and of having been drunk multiple times, but there were differences in the pattern for young people of different ages.

Claire Turner, Programme Manager for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, said:

“This research shows that parents can have more influence on their teenagers’ behaviour than perhaps many assumed. Both what parents say, and how they behave, have a strong impact on their teenagers drinking, drinking regularly, and drinking to excess.”

Bremner, P; Burnett, J; Nunney, F; Ravat, M; Mistral, W: Young people, alcohol and influences – A study of young people and their relationship with alcohol. Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2011

School alcohol education programmes can work, review finds

School prevention programmes aimed at curbing alcohol misuse in children can be effective, according to a large, international systematic review. The findings undermine the frequently made claim that school based alcohol education programmes are wholly ineffective.

The review found that the most significant programme effects were reductions in episodes of drunkenness and binge drinking. School-based prevention programmes that take a social skills-oriented approach or that focus on classroom behavior management can work to reduce alcohol problems in young people,” said David Foxcroft, lead review author. “However, there is good evidence that these sorts of approaches are not always effective.”

David Foxcroft, a psychologist at Oxford Brookes University, in England, and co-author Alexander Tsertsvadze, at the University of Ottawa Evidence-Based Practice Center, in Canada, analyzed 53 randomized controlled trials done in a wide range of countries with youth aged 5 to 18 when studies began. Forty-one studies took place in North America, six in Europe and six in Australia. One was conducted in India and one in Swaziland. Two studies took place in multiple locations.

The studies were divided into two major groups based on the nature of the prevention program:

- programs specifically targeting prevention or reduction of alcohol misuse

- generic programs with wider focus for prevention, for example other drug use/abuse, antisocial behavior

The review found studies that showed no effects of the preventive programme, as well as studies that demonstrated statistically significant effects. There was no easily discernible pattern in programme characteristics that would distinguish studies with positive results from those with no effects. Most commonly observed positive effects across programmes were for drunkenness and binge drinking. The authors conclude that current evidence suggests that certain generic psychosocial and developmental prevention programmes can be effective and could be considered as policy and practice options. These include the Life Skills Training Program, the Unplugged program, and the Good Behaviour Game.

The review appears in the May 2011 issue of The Cochrane Library, a publication of The Cochrane Collaboration, an international organisation that evaluates medical research. Systematic reviews draw evidence-based conclusions about medical practice after considering both the content and quality of existing medical trials on a topic.

Foxcroft, D; Tsertsvadze, A: Universal school-based prevention programs for alcohol misuse in young people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 5

Nine year old boy arrested for drink driving

Police records have shown a boy aged nine was arrested for drink driving.

The boy, from Cumbria, was breathalysed and taken into police custody. However, when officers discovered his age, they were forced to release him without charge as he was too young to be held accountable for his actions.

No further information is available about the circumstances of the case, such as how much alcohol the boy had consumed or how he had obtained it.

Safety campaigners have since demanded action to curb juvenile car crime.

The child, who has not been named, was just one of thousands of under 18s arrested in the north of England over the past two years. These included four 11-year-olds and a 10-year-old arrested in the Northumbria force area for car theft, and seven 12-year-olds arrested in Cleveland for the same crime. During the same time period, Durham Police arrested one 12-year-old for aggravated vehicle taking and North Yorkshire Police arrested one 10-year-old for car theft. These were among 2,467 juveniles arrested for crimes including car theft, aggravated vehicle taking, drink driving and underage driving.

Kath Hartley, of the charity Brake, which campaigns for lower speed limits, demanded road safety education be taught in school. She told The Sunday Sun in Newcastle: “It is incredibly concerning that young people are risking their own and other people’s lives on the road. This must be addressed as a matter of urgency.”

Source: Press Association

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

Gambling industry harms and parallels with the alcohol world

Will Prochaska –

Coalition to End Gambling Ads