In this month’s alert

Alcohol policy sponsored by Bass – …its like putting the wolf in charge of the sheepfold

The Conservative Government had an alcohol policy but failed to achieve its main targets. It simply fizzled out. Although the statistics relating to drink driving improved enormously, the ministers of the day refused to look for further advances by lowering the legal alcohol limit. Labour came to power on the promise of following this course and formulating a new and improved alcohol strategy. This was to be combined with far-reaching liberalisation of the licensing laws. Here we review the strange course of alcohol policy since the advent of the Labour Government.

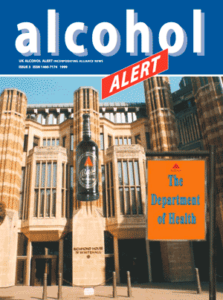

In an astonishing move, the Government has put the formation of its alcohol policy partially into the hands of the drink industry. At this moment John Poleglass is working in the Department of Health shaping the way in which this country approaches the alcohol problem which dwarfs those caused by all the illegal drugs combined. Mr Poleglass has been seconded for this task from the sales department of Bass Breweries, usually regarded as one of the most aggressive companies when it comes to marketing its products including the notorious alcopop Hooper’s Hooch. Critics comment that this is rather like putting the wolf in charge of the sheepfold.

Cut links

Commenting on the Bass secondment, the Institute of Alcohol Studies said that the government’s new strategy for tackling alcohol misuse will only work if ministers are prepared to risk their close relationship with the alcohol industry. The Institute of Alcohol Studies, claimed that the government is “hand in hand” with the alcohol producers, and that the relationship could compromise any attempt to solve the problem. An IAS spokesman said: “All the appearances are that the government has a rather closer relationship with the alcohol industry than is desirable or is in the public interest… The government is giving the alcohol industry a place right at the centre of policy making that I don’t think they would give to any other industry in a similar situation.”

Policy

In the spirit of “joined-up government”, the vogue phrase of the moment, alcohol policy was to be approached from all angles and be the result of co-operation between all interested departments.

The appointment of Tessa Jowell as Public Health Minister in 1997 was seen as an indication of the new Government’s approach to public health policy of which a tough line against illegal drugs and smoking would be a main component. There were, however, mixed signals in relation to the Government’s policy on alcohol. The Government made efforts to tackle alcopops, but its commitment to relaxing the licensing laws was clear and the Chancellor appeared unwilling to increase taxes on alcohol significantly.

Already the power of the drinks industry was making itself felt, especially through its fiscal significance. It could also be argued that the determination to liberalise the licensing laws appears to have had a wider effect in that the inevitable involvement of the industry in this area has eased its entry into the wider field of alcohol policy.

In late 1997 Mrs Jowell announced that the Government was to launch a new approach to public health strategy designed to tackle ‘the root causes of ill health and, especially, health inequalities’. The implications of the proposed new approach for alcohol policy were unclear. Under the previous Government, the principal targets in relation to alcohol policy were contained in its health strategy, ‘Health of the Nation’. The targets were reduced proportions of adults exceeding the ‘sensible limits’.With the benefit of hindsight it seems likely that the argument was continuing within the Department of Health, or between different departments, as to which path should be taken. Would the Government follow the World Health Organization’s recommendation and aim for a significant cut in consumption or would it prefer to regard alcohol problems as limited to those who ‘abuse’ the substance?

National Strategy

Alcohol Concern, whose Proposals for a National Alcohol Strategy for England was published earlier this year, has formally written to the Department of Health to protest at this extraordinary extension of drink industry influence. The Department has pointed out that it does not have the manpower to carry out the task of formulating the Government’s alcohol policy and that Mr Poleglass will work in tandem with someone with a health promotion background. At the time of writing, this other person has not yet been appointed, whilst Mr Poleglass of Bass Breweries has been in post for over two months.

The Government published its useful “Statistics on Alcohol: 1976 onwards” at the beginning of October and Tessa Jowell, still at that point Minister for Public Health, had this to say: “It also indicates that the majority of people in this country drink at levels that are not likely to be harmful. As we announced in the White Paper “Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation”, we are currently developing the new strategy, in partnership with all the sectors involved: government departments, health and social services, the alcohol industry and law enforcement agencies. The agreed strategy will be published early in the next Millennium.” Early in the next millennium, of course, leaves plenty of scope for delay, but the significant thing about Mrs Jowell’s remarks are the positioning of the industry alongside the health services, the absence of any mention of agencies such as Alcohol Concern, and the implied minimisation of the problem. Mrs Jowell during her time at the Department of Health listened carefully to the industry’s mouthpiece, the Portman Group, and shared its vocabulary. At the same time she set her face resolutely against the per capita consumption model of the alcohol problem, putting this Government out of step not only with the World Health Organization but also with the majority of other governments in Europe. It will be interesting to see whether the changes made by the Prime Minister at the Department of Health will bring about any changes to the formation of alcohol policy.

After the general election of May 1997, there was a great deal of speculation as to the new Government’s attitude. There were hopes for progress in a number of areas affecting alcohol policy. From the start Alert monitored events and attempted to read the auspices.

Alcopops

Having made threatening noises about alcopop advertising, the Government backed down. Two years ago, these Government threats were exposed largely as bluff when the much heralded Government crack-down gave the industry yet another last chance to ‘prove that self-regulation works’. Critics, including the Institute of Alcohol Studies, welcomed some of the moves but said they did not go far enough and relied too heavily on self-regulation by the alcohol industry. This had already been shown to be ineffective.

Even at this stage, within months of taking power, the signs were that Mrs Jowell and other ministers involved in the subject were listening to the Portman Group, the industry’s mouthpiece, rather than health professionals. In his first Budget, Gordon Brown, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, also disappointed expectations by ignoring the demands for a major tax increase on alcopops in his first Budget. In the event, despite the intense public clamour, and the fact that the alcopop manufacturers were clearly braced for a large tax increase, the Chancellor made no specific reference to the drinks and the tax on alcopops was increased only in line with inflation, along with all other alcoholic drinks. In contrast, in his last budget, Mr Brown’s predecessor as Chancellor, Kenneth Clarke, increased the tax on alcopops by around 8 pence in response to worries about their popularity with under age drinkers.

Later in 1998 the way policy was likely to develop was further indicated by the Ministerial Group on Alcopops’ endorsement of the work of the Portman Group. The ministers said that they were “much encouraged” by the success of the Group’s Code of Practice on the Naming, Packaging, and Merchandising of Alcoholic Drinks. “There are fewer complaints made under the new Code and where they occur and are upheld, swift compliance with the independent panel’s decisions is the norm.”

The Ministerial Group on Alcopops issued their upbeat statement at a time of increasing concern about the extent and effects of under-age drinking.

Drink-driving

As early as the beginning of 1998 a weakening of the Government’s commitment to lowering the limit was evident. Despite all indications that this would have overwhelming public support, there were reported divisions in the Cabinet on the topic, with the Prime Minister himself remaining unconvinced. Ministers questioning the lower limit cited the ‘nanny state’ image and damage to country pubs as their main concerns.

Despite a U-turn on the drink-drive limit seeming possible, the Government’s own consultation document, Combating Drink – Driving – Next Steps, issued by the Department of the Environment, Transport, and the Regions, made a good case for the lower limit. It made the point that “about 80 road users per year are killed in accidents where at least one driver had blood alcohol over 50mg but where no driver had blood alcohol over 80mg.” The government’s stated opinion then was that at least 50 of these lives could be saved if the legal limit were reduced to 50mg and enforced as efficiently as the current limit.” The estimate is that, in addition, approximately 250 serious and 1200 slight injuries could be prevented.

Road safety campaigners will of course be aware that the Governments’ estimate of the number of lives saved by cutting the legal limit substantially exceed the number of lives lost in the Paddington rail disaster, the huge national reaction to which was led by Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott.

During the course of the year there was further evidence that the Government was having second thoughts about the lower limit. Alert reported a Road Safety and Health conference organised by PACTS (The Parliamentary Advisory Council for Transport Safety) at which Lord Whitty, the minister for roads, spoke. He refused to commit the government to lowering the drink-drive limit – an intention stated clearly both before the general election and immediately afterwards. The signs are that pressure to stick with the high 80 mgs per cent have paid off. At the same conference Tessa Jowell outlined the problems associated with road safety and failed even to mention drink driving.

It is reported that Ministers will shortly announce that they are setting a target of a 40 per cent reduction in the death toll during the next ten years. Enforcement of the drink-drive laws will be the main priority, along with stronger anti-speeding measures.

Lord Whitty said recently: “Later this year we intend to publish our new, comprehensive strategy to reduce casualties still further during the next ten years. That strategy will cover driving standards, speed limits, infrastructure, vehicle design, pedestrian protection, cycling and motorcycle safety, as well as enforcement and penalties, and publicity and education.”

It is understood that the new road safety strategy is written and awaiting release. However, the legal blood alcohol level is left blank in the document, Ministers still not having decided what it will be.

Road Safety Campaigners will also recall that it 1991 Mr Prescott himself called for the legal limit to be reduced to 50 mg per cent.

No nannies

As 1998 progressed it became increasingly apparent that the Government was listening more and more to the Portman Group and the industry. In the spirit of New Labour’s obsession with being ‘on message’ their vocabulary was often almost identical:

“The ‘sensible drinking’ approach to reducing alcohol-related problems is being re-examined by the government in the context of its health strategies for England, Scotland, and Wales.

“The government has made it clear that it intends to tackle drinking and driving and alcohol-related violence. Ministers are anxious to distance themselves from the image of their’s as the nanny state party, and, in the green papers recently issued, they appear to be undecided as to whether they wish to continue the ‘sensible limits’ approach to alcohol education and to keep in place the health targets based on those limits promulgated by their Conservative predecessors. However, whilst soliciting views on this issue, Health Ministers have given their backing to the Portman Group’s new campaign, ‘It All Adds Up!’, which seems to indicate that the revised ‘sensible drinking’ limits introduced by the previous government will be endorsed.”

When Frank Dobson, the then Secretary of State for Health, presented the Green Paper for ‘Our Healthier Nation’ to the Commons, it was clear that he and other Labour ministers were positioning themselves to steal a march on the Tories by portraying the Opposition as the advocates of the nanny state. Concern was expressed that the tone of the paragraph on alcohol in the green paper implied a watering-down of the Government’s attitude to the problem and the abandonment of the commitments set out in the Conservatives’ Health of the Nation, where it was stated that:

- “health will be one of the factors taken into account by the Chancellor of the Exchequer in deciding alcohol duties.

- the commitment within the framework of the family health services to the promotion of the sensible drinking message will be strengthened.

- an agreed format for the display of customer information on alcohol units at point of sale will be considered jointly with the alcohol trade associations.

- there will be a new initiative to monitor the penetration of the sensible drinking message.

- continued encouragement will be giv-en to employers to introduce workplace alcohol policies and to monitor their impact.

- the expansion and improvement of voluntary sector service provision.”

| PREPARING THE WAY FOR THE NEW ALCOHOL MISUSE STRATEGY

In one of her last statements as the Minister for Public Health, Tessa Jowell, said she was preparing the way for the new alcohol strategy with the publication of the Department of Health’s bulletin “Statistics on Alcohol: 1976 onwards”. “The publication of this bulletin, said Mrs Jowell, “is an important step towards bringing together key data on alcohol consumption. Our aims are two-fold: to increase public understanding of sensible drinking limits and to continue efforts to tackle alcohol misuse. “Alcohol misuse affects individuals, families and society at large. It is an important issue not only in terms of its effects on health, but also on public order and safety. The bulletin highlights some areas that are of great concern, including:

“It also indicates that the majority of people in this country drink at levels that are not likely to be harmful. “As we announced in the White Paper “Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation”, we are currently developing the new strategy, in partnership with all the sectors involved: government departments, health and social services, the alcohol industry and law enforcement agencies. The agreed strategy will be published early in the next Millennium.” STATISTICS ON ALCOHOL: 1976 ONWARDS A summary of the Statistical Bulletin quotes some of the figures against which the success or failure of any alcohol strategy will be measured:

|

Budget

In his 1998 Budget, Gordon Brown strengthened the impression that the drink industry was to be treated with kid gloves. Despite the automatic cries of “Foul!” from the industry, the Chancellor in effect left the alcohol question on hold. He could have gone either of two ways. In order to combat the considerable problem of cross-channel smuggling, he might have taken the bold step of slashing duty as demanded by the industry. On the other hand, he had the opportunity of listening to the public health lobby and imposing increases which would have had a real effect on consumption. He has chosen to temporise.The argument that tax increases have a direct impact on public health and the environment is accepted in the cases of tobacco and petrol, but not when it comes to alcohol, was the clear implication of Gordon Brown’s budget. Whilst a swingeing 20p was added to the price of a packet of cigarettes, beer escaped with 1p a pint, wine with 4p a bottle, and for spirits there was no increase at all. In other words, the Chancellor did no more than keep any alcohol price rises in line with inflation and these were not to come into effect until 1st January, 1999.

Alcohol also escaped virtually scot free in the 1999 Budget when the Chancellor said that duty on alcohol would not be increased before the Millennium. It seemed that the most important thing was not to mar in any way the booze-up planned for the end of the century. The only alcoholic drinks to be subject to any increase were sparkling cider and low-strength sparkling wine – an insignificant section of the market.

Our Healthier Nation

One of the most important events of the year in the run up to the formulation of the Government’s own alcohol policy was the launching of Alcohol Concern’s proposals for a national strategy.

The green paper Our Healthier Nation committed the Government to such a strategy and, in enlisting the help of Alcohol Concern, it allowed extensive consultations to take place. It seemed likely that some of the conclusions drawn in the proposals would meet opposition:

“Given the government’s rejection of a strategy to reduce per capita consumption, the first objective in Alcohol Concern’s proposals may not be welcomed by ministers. It reads: ‘Should the annual national consumption of pure alcohol rise to more than 8 litres per head of the population, the highest recorded level since 1965 being 7.8 litres, accompanied by evidence of a rise in alcohol misuse, [the objective will be] to reduce levels of consumption to those rates pertaining when the strategy came into operation.’ This is a modest aim since the latest figures available show that 7.6 litres of pure alcohol were consumed per head of the entire population (9.4 litres for those aged 15 and over).” (Alert, No. 2, 1999).

The proposals needed to be seen in the context of the World Health Organization’s aim as set out in the first European Alcohol Action Plan (EAAP) which was to reduce consumption by an ambitious 25 per cent. Whilst this has been met in only three countries, others are taking measures to approach the target, possibly by the end of the second EAAP in 2004. In France the intention is, by the turn of the millennium, to reduce the average consumption of alcohol by people over 15 by 20 per cent. In Spain, the Health Minister recently declared that a reduction in the per capita consumption of alcohol was the “path that we have to follow if we do not wish to pay the high price implied by the scientific evidence. This evidence categorically shows that higher levels of consumption go with higher rates of sickness and mortality.”

New brooms

We are often told to concentrate on issues rather than personalities, but it would be foolish to ignore the possible effects of the significant changes in the ministerial ranks of the Department of Health. Alan Milburn, who takes over as Secretary of State for Health, is regarded at the age of 41 as a man to watch. He has already served a term as a junior minister at Health before becoming Chief Secretary to the Treasury. Whether the influence of the Portman Group will continue under Mr Milburn is debatable. In 1995 the All-Party group on Alcohol Misuse, which he chaired, brought out an important report, Alcohol and Crime: Breaking the Link. Alan Milburn’s committee recommended that the government should sponsor a high profile, national campaign, similar to that on drink driving, to combat alcohol and crime, especially where violence is involved. In addition, the All-Party Group report concluded that the contribution of alcohol to crime was such that the charge for liquor licences should be increased to cover the cost of alcohol education for offenders. Mr Milburn’s efforts were attacked by the Portman Group which attempted a spoiling tactic by bringing out its own report attempting to demonstrate that there was no proven connection between alcohol and crime – a report which was greeted with incredulity and ridicule. The new Secretary of State may well remember the incident now that his has the overall responsibility for alcohol policy.

The other major change at the Department of Health is the departure of Tessa Jowell who has gone to Education. She is replaced as Minister for Public Health by Yvette Cooper. Miss Cooper is only 30. She entered the Commons in 1997 as Member for Pontefract and Castleford and is regarded as one of the most able of that intake.

Perhaps the changes will bring about a policy influenced more by the agencies dealing with alcohol problems than by vested interest.

Tackling alcohol together

Andrew McNeill writes

In 1979, the National Council on Alcoholism (NCA), the forerunner of Alcohol Concern, was instructed by Health Minister Sir George Young to become engaged in the prevention as well as the treatment of alcohol problems.

‘Prevention’, Sir George said, ‘does not raise medical issues but political ones, since it presupposes the adjustment of a nation’s lifestyle to improve its health… For many of today’s problems the answer may not be cure by incision at the operating table but prevention by decision at the Cabinet table.’

This instruction prompted the NCA to set up a prevention committee, and the main idea it discussed was the possibility of helping politicians to make policy by collecting together in one publication all the available evidence on alcohol problems in England and Wales (Scotland has its own national agency) and successful methods of preventing them.

Twenty years later, this publication has finally appeared. It is called `Tackling Alcohol Together: The Evidence Base for a UK Alcohol Policy’. It has been produced by the Society for the Study of Addiction, and an excellent job the Society has made of it. The Society brought together an impressive team of scientists, researchers and practitioners led by Duncan Raistrick, Ray Hodgson and Bruce Ritson and they have succeeded in at last writing the book that people involved in alcohol policy in the UK have needed for little short of a generation.

The book’s title is, of course, a reference to `Tackling Drugs to Build a Better Britain’, the name given to the Government’s strategy against the misuse of illegal drugs. One point being made by the authors is that the drugs problem has been regarded for a number of years as warranting a clear national strategy whereas the alcohol problem has not, even though the harm from alcohol far exceeds that from illegal drugs. Another is that the drugs strategy shows the way in which different sectors can be encouraged to work together to a common purpose, a main theme of this book.

Tackling Alcohol Together is a sister volume to `Alcohol Policy and the Public Good’, the book written by Professor Griffith Edwards and his colleagues to provide the scientific evidence underpinning the World Health Organization’s Alcohol Action Plan for Europe. As its sub-title indicates, the new book covers much the same ground but specifically with reference to the UK. It should also be seen in conjunction with Alcohol Concern’s Proposals for a National Alcohol Strategy, (featured in issue No2. 99).

Tackling Alcohol Together provides a wealth of information and analysis of alcohol consumption and related harm; influences such as price and legal availability of alcohol on drinking behaviour and related problems, and on policy initiatives to reduce alcohol problems. The standard is consistently high and the discussions of alcohol policy issues are in general superior to Alcohol Policy and the Public Good. There are particularly useful discussions of the complex issue of alcohol, crime and violence and the related topic of liquor licensing.

Like its sister volume, Tackling Alcohol Together represents and promotes an evidence-based approach to alcohol policy. There is now a mass of evidence on the causes of alcohol problems and on methods of preventing and treating them and this evidence, so ably presented by the authors, should, they argue, provide the basis of a comprehensive national alcohol policy.

As the summary of recommendations makes clear, a key element of an evidence-based strategy is control of the overall level of alcohol consumption. Because of the strong relationship between per capita consumption and the level of alcohol problems in the whole population, Tackling Alcohol Together advocates reducing per capita alcohol consumption to below 8 litres per annum, a level not seen since the early 1970s. The authors conclude that alcohol taxation provides the principal means of achieving this objective. There are no proposals in regard to alcohol advertising, other than continued enforcement of the advertising code, because there is a lack of evidence to justify stronger measures.

The absence of a recommendation to restrict or ban alcohol advertising will be one of the few features of this book to be welcomed by the alcohol industry. In contrast, the objective of reducing national consumption of alcohol will of course arouse its implacable opposition. All the indications are that the Government’s reactions will be similar, and it is in this connection that a worrying degree of naivety is apparent.

The clear hope and belief of the authors is that with the arrival of New Labour, the alcohol policy promised land is in sight. Indeed, they state that, prior to the publication of the Green Paper `Our Healthier Nation’ in 1998, no UK Government had ever deemed it necessary even to propose a national alcohol strategy, let alone implement one. This is an odd claim to make, as it means disregarding the whole of the alcohol component of previous Conservative Governments’ health strategy. This included targets for reducing the number of heavy drinkers in the population, a commitment to taking public health into account in setting alcohol taxes and the setting up of an interdepartmental ministerial group on alcohol misuse to coordinate activity. It is, of course, true that the Conservatives failed to achieve their own targets, that the Ministerial Group was allowed to fizzle out, and that lots of other things happened or did not happen that worked against reduced levels of alcohol related harm. But to disagree with a policy, or to criticise the ineffective way it is implemented, is quite different from denying that it exists, and to deny the title of `alcohol policy’ to the Conservatives’ efforts may be thought to be taking political partisanship a bit far.

It may also result in a great deal of disappointment, as there is no obvious reason to believe that the present Government is any more receptive than its predecessors to the proposals contained in Tackling Alcohol Together. Indeed, the indications are that it may turn out to be less receptive.

Tackling Alcohol Together is a considerable achievment. It will or should significantly raise the level of knowledge and debate and it fully deserves to be a landmark publication in relation to the development of national policy. Whether it actually will be depends on people other than the authors.

Tackling Alcohol Together: The Objectives of the National Alcohol Policy

1 – To increase Public Information and Debate about Alcohol

There are four key proposals to support this objective:

- Create a national and local structure to coordinate action on alcohol. The chosen structure needs to be led at ministerial level.

- Funding to ensure the availability of statistical information, surveys and research. Research needs to meet the …. requirements of producing definitive answers within planned programmes of investigation

- Promulgate a simple safe Iimits message supported by labelling of alcohol content of drinks.

- Designated people at national and local levels to develop the skills of media advocacy and build positive media relations

Strategy One – Public Health Promotion Campaigns Linked To Encouragement of Local Action

Agencies such as the Health Education Authority, Health Education Board in Scotland, or Health Promotion Wales would he expected to take a lead role in this strategy, but it would he important to build partnerships that can deliver local action to coincide with centrally coordinated mass media campaigns.

Strategy Two – Working with the media to ensure accurate reporting of alcohol issues and encourage public debate

A central Alcohol Policy Coordinating Unit would probably claim the right to own this strategy, but an independent agency such as Alcohol Concern might be more proactive and adhere more innovatively to the spirit of the strategy. The regional network of Alcohol Concern lends itself to coordinating active public debate.

2 – To Encourage the Drinks and Leisure Industries to Introduce Innovative Schemes to Discourage ‘Drunkenness’

There are four key proposals to support this objective:

- Extend the role of drug action teams to include alcohol and be responsible for community action.

- Evidence-based reform of the Iicensing regulations to harmonise national and local controls. Licensing should include criteria of need and monitoring of untoward incidents associated with licensed premises.

- Licensing should require server training and seek to agree a fair system of server liability in the drinks trade.

- Set priorities for local enforcement schemes including those based on incident monitoring.

Strategy Three – Innovation to Encourage Safer Drinking Environments

The drinks and leisure industries are well able to develop their business, but what is needed is encouragement and commitment to developments within the intentions of the alcohol strategy, perhaps through formal controls. Providing family areas in pubs or ensuring public transport to service pubs in the late evening are two examples.

Strategy Four – Enforcement of Legislation and Agreements with Automatic Sanctions for Transgressions

Local police action in partnership with licensing magistrates, town planners and representatives of the trade would be one way of leading on this strategy.

3 – To Maximise Community and Domestic Safety

There are four key proposals to support this objective:

- Zero tolerance of domestic violence. This requires local schemes that enable the immediate removal of violent drinkers from the home into treatment programmes backed by legal sanctions.

- Reduce prescribed limit for drinking and driving to a blood alcohol level of 50 mg%. There should be harmonisation of drink driving laws across Europe. Appraisal of vehicle immobilisers should be undertaken as a medium-term strategy.

- Increase the age limit for selected drinking related activities.

- Incentives and support for employers to develop workplace policies and employee assistance programmes.

Strategy Five – Take Action to Prevent and Reduce Accidents and Other Untoward Incidents Relating to Drinking

National campaigns would be the backdrop to action which would be mainly local and coordinated through the Drug Action Teams or their alcohol equivalents. Public support against drinking and driving needs to be extended to other behaviours where drinking causes unacceptable risks or nuisance.

Strategy Six – Take Action to Prevent and Reduce Violence or Nuisance Related to Drinking

The national legislation required to implement this strategy is already in place. What is needed is collaboration between local police, social services and probation services backed by a commitment from the Drug Action Teams or their alcohol equivalent to take action. Intolerance of intoxication leading to violence needs to permeate our culture.

4 – To Reduce Alcohol Related Health Problems Below 1990 Indicator Levels

There are four key proposals to support this objective.

- Fiscal measures to maintain per capita consumption below 8 litres of absolute alcohol. These measures should be declared in the Chancellor’s annual budget statement.

- Establish a network of addiction training centres and accredited courses. Training is a prerequisite if services are to match their potential as described – this review of treatment outcome research.

- Create incentives for generic services to become effective at delivering minimal interventions. Efforts need to extend beyond primary health care into Social services, probation and others.

- Ensure that equal access to specialist NHS units is available in all health authority districts. Specialist services need to be of a standard not only to deliver more complex treatment, but also to to undertake research and contribute to training and policy initiatives.

Strategy Seven – Maintain per capita Consumption at or below 1990 Levels

Once commitment is achieved, implementation of this strategy is ultimately a technical, Treasury exercise. If other measures to contain consumption fail then government can deploy fiscal measures to contain per capita consumption down to predeter!nined levels. Also implied is concurrent public education to create a climate of understanding that would make such measures practical and acceptable.

Strategy Eight – Implement a Comprehensive Health Service Response to Alcohol Problems

It is expected that the Department of Health, which already has mechanisms for influencing and monitoring treatment services, would continue to take the lead role for this strategy. It is important that funding arrangements reflect the broad remit of specialist services within a health district.

‘I have a vision of the future, chum…’

Although they will enjoy increased prosperity over the next decade, the people of the United Kingdom will pay the price of greater levels of stress, longer working hours (despite already having the longest in Europe), and impoverished family life. Such are the gloomy prognostications of The Paradox of Prosperity, a report commissioned by the Salvation Army from the Henley Centre.

In addition there will be more people living alone and greater numbers of self-employed. The necessity of working to support elderly relatives and to pay into private pension schemes will add to the pressure. As a consequence of this and the near impossibility of escaping from the cycle, there will be greater abuse of alcohol and illegal drugs as people look for a way of coping. The report says that 4.7 per cent of adults are dependent on alcohol and 2.2 per cent on illegal drugs. It estimates one in 28 men and one in 12 women are on anti-depressants. The inevitable result of this, says the report, will be an even higher rate of divorce and family breakdown than there is at present. Increased isolation will lead to the greater use of counselling services, over which there is little regulation at the moment, as well as dependence on drugs and alcohol. The Salvation Army has an honourable history of tackling these problems and clearly sees this continuing on a greater scale as time moves on. The understandable assumption is made that stress leads automatically to alcohol abuse. Many studies do show that there is a link, but others cast doubt on the connexion. The relationship is complex and too simple a view of the situation helps neither diagnosis nor cure. Among social drinkers quite the opposite may be the case since the onset of stress, if this is taken to imply elements of depression, can lead to a cessation of social activity and a consequent lowering of alcohol intake. Among established alcoholics there is a stronger causal association of stress and drinking, although it must be remembered that alcohol is itself a physiological stressor, and, for alcoholics in recovery, stress can be a cause of relapse.

The report tells us that there will be a 35 per cent increase in wealth, but that the top 10 per cent will be 10 times richer than the bottom 10 per cent. The prediction is that the gap will be exacerbated by the advances in information technology. There will be more people in what has become known as a “care sandwich”, looking after children on the one hand and their parents on the other. One of the reasons for this is that couples are having children at a later age. Another is that, with the withering away of the state pension, parents are more likely to be financially dependent as well as suffering increased longevity.

Further dire warnings are that there will be a 55 per cent increase in one-person households by 2011 and therefore even less support from the family unit. There will be a third more one-parent households. We are told that almost a quarter of women will still be childless at the age of 45, compared with 16 per cent in 1997.

“Society will have become a collection of individuals mixing and matching their own set of values and this will have an additional, negative, knock-on effect on community life,” the report concludes. One possible implication of this may be that people will look to religious organisations, such as the 130-year-old Army, to find meaning in life.

The “general loss of meaning in our lives” will lead to a “search for spiritual meaning” which in in recent years has been manifested in the growth of fringe cults rather than in the mainstream religions. The traditional denominations have failed “to inspire sufficient trust and confidence” partly, it might be said, by attempting to accommodate themselves too closely to the spirit of age. The Salvation Army and the other denominations are therefore presented with both a challenge and an opportunity. In the mean time there will be more work for the alcohol and drug agencies.

Alcohol and crime

Some early indications of what may and may not be included in the Government’s alcohol strategy are provided by a new Home Office report, Alcohol and Crime: Taking Stock.

Publication of the report prompted the government to reaffirm that pubs and the police need to take effective action against alcohol-related violence and that to achieve this, it wants greater use of pub exclusions, laws on anti-social behaviour, and alcohol bye-laws.

However, the report conspicuously avoids reference to known links between violent crime and the overall level of alcohol consumption even though it was previous Home Office research that drew particular attention to them. The study found that growth in beer consumption was the most important single factor explaining growth in violent crime. The new report also sidesteps most of the issues concerned with liquor licensing.

The Report

The report states that more than 13,000 violent incidents occur in and around pubs in England and Wales every week. It suggests greater use of pub bouncers, tougher glass to reduce injuries, more food provision to soak up alcohol, and better public transport to cut down on drinking and driving.

The government also proposes a media campaign to promote “sensible drinking”, greater use of treatment programmes for those convicted of alcohol-related crimes, and better training of police officers dealing with the problem.

The report found that more than half of the 400 crime and disorder partnerships between police and other agencies in England and Wales have a specific policy on alcohol-related crime. Charles Clarke, the Home Office minister said, “I want to see more such partnerships at this level which include publicans and other in the alcohol industry.”

The Home Office study was launched at the Alcohol Concern annual conference in November, this year devoted to the theme of ‘Alcohol, Crime, and Disorder’. Mr Clarke told delegates: “Alcohol-related crime is a significant problem in society – a problem which has no single cause and no magic solution.

“I am particularly pleased with today’s recommendations for more joined-up action – only by working together across government, law enforcement, voluntary agencies, and the licensed trade can we reduce crime linked to alcohol abuse.”

Early next year the government is to host a seminar of key figures in the area of alcohol and crime and will be publishing examples of good practice in combating the problem.

In a survey published at the same time as the Home Office report, Alcohol Concern says police believe alcohol to be a far greater problem for them than illicit drugs. It says 68 per cent of officers encountered alcohol-related crime and disorder every day, 96 per cent thought crime statistics did not properly show the scale of the problem, and 84 per cent thought insufficient priority was given to schemes to tackle it. The counter-measures which most officers preferred were a ban on drinking in the streets and tougher penalties for offenders.

Drawing on the most recent research in the area, the report highlights the complex relationship between alcohol and crime. Causal relationships between the two include offences which occur because the offender has consumed alcohol, typically public disturbance and domestic violence. Contributory relationships include “drinking for ‘dutch courage’ to facilitate an offence which requires an element of courage, alcohol acting as a trigger, or used as an excuse for offending behaviour.” Organisations working in gaols, such as the Rehabilitation of Addicted Prisoners Trust (RAPt), are only too aware of the number of men and women serving sentences as a consequence of alcohol misuse. Some of them, of course, are imprisoned because it is difficult to be an efficient burglar with faculties blunted by alcohol. Many professional criminals find methadone a more reliable tool when “bottle” is required.

Although the the relationship between alcohol and aggression is not simple, says the report, “a high proportion of violent crime (50 to 80 per cent), including assault, rape, and homicide, is committed by an intoxicated person”. 125,000 of the half a million facial injuries suffered in the United Kingdom every year are the result of violence and in the “majority of cases (61 per cent) either the victim or the assailant had been drinking alcohol”.

Alcohol and Crime: Taking Stock emphasises the importance of proper training for licensees and the control of the drinking environment. “Maintaining premises, training staff to deal with intoxicated customers, promoting alcohol in a sensible manner, filtering patrons from licensed premises by using staggered closing times can all be elements in an overall strategy.”

The report concludes with a statement of the need for a co-ordinated approach. It quotes Alcohol Concern’s recent proposals for a national alcohol strategy in stating that the problem should be tackled by “focusing not only on the individual but on society as a whole”.

New alcohol action plan for Europe…

The World Health Organization (WHO) is about to embark on the Third Phase of the European Alcohol Action Plan, EAAP 2000-2005.

The objectives of EAAP 2000-2005 are to take a wide range of measures to address the task of preventing the harm that can be done by alcohol, such as fatalities, accidents, violence, child abuse and neglect, and family crises. The intention is to provide both accessible and effective treatment for people who are alcohol dependent or consuming at a hazardous rate and greater protection for children, young people, and those who choose not to drink alcohol from the pressures to drink.

The WHO says that “the ten strategies set out in the European Charter on Alcohol provide the framework for EAAP during the period 2000-2005”.

One of its most important new initiatives is to include in the Action Plan a Europe-wide ban on alcohol advertising at sporting events and on advertisements aimed specifically at young people. A co-ordinated initiative across the Region is required because individual countries are finding it difficult, as a result of the pressures of international competition, to implement a ban which covers all domestic and foreign parts of the alcohol industry.

The WHO also stresses the continuing need for all countries to reduce per capita alcohol consumption. Furthermore, It is “important that messages about safe drinking were clearly seen to be coming from public health experts, and not from industry sources”.

The WHO intends to look for better ways of communicating with the alcohol industry. Given that the most important aim of the first phase of the Action Plan was a 25 per cent reduction in overall consumption of alcohol throughout the European Region, the relationship with the industry has not been easy.

In its evaluation of the first two phases of the EAAP, the WHO points out that Alcohol products are responsible for 9 per cent of the total disease burden within the Region. Alcohol is “linked to accidents and violence and are responsible for a large proportion of the reduced life expectancy in the countries of the former Soviet Union. Reducing the harm that can be done by alcohol is one of the most important public health actions that countries can take to improve the quality of life”.

Social harm

The WHO, surveying the range of damage done by alcohol in the European Region, goes on to say that “alcohol products are responsible for some 9 per cent of the total disease burden within the Region”. This harm done is particularly high in the eastern part of the Region, the former Communist states, and was a major contributor to the reduction in life expectancy which occurred there during the 1990s. Between 40 per cent and 60 per cent of all deaths in the European Region from intentional and unintentional injury are attributable to alcohol consumption. Alcohol use and alcohol-related harm, such as drunkenness, binge drinking, and alcohol-related social problems, are common among adolescents and young people, especially in western Europe.

The harm done by alcohol imposes a major economic burden on individuals, families, and society through medical costs, lost productivity arising from increased morbidity, costs from fire and damage to property, and the loss of income to the family due to early mortality. The costs of alcohol to society are estimated at between 2 per cent and 5 per cent of the gross national product.

The drink industry

Addressing itself to the responsibility of the industry, the WHO says that by the year 2005, all countries of the European Region should ensure that there is a reduction in alcohol-related problems within the drinking environment with fewer intoxicated persons leaving licensed premises and subsequently involved in assaults, violence, and alcohol-related traffic accidents. There should also be effective measures introduced to restrict young people’s access to alcohol.

As part of the drive to realise these aims, there should be “health impact assessments, which evaluate the effect of the alcohol industry’s social and economic policies and programmes on health, in order to ensure accountability.” In addition, the concept of product liability should be extended to cover those who promote alcoholic beverages in an irresponsible and inappropriate way. Regulations governing the alcohol content, packaging, and marketing of alcoholic products should be introduced. Training programmes for those serving alcoholic beverages should be provided to ensure personal, ethical, and legal responsibility. Legislation should be introduced so that those “who serve alcohol in an irresponsible manner are held accountable by means of server liability, licence withdrawal or other mechanisms deemed appropriate by the authorities.”

The WHO also believes that there should be strict enforcement of existing licensing and drinking laws, compulsory training requirements and conditions placed on licences which prohibit irresponsible trading practices within the drinking environment.

The Amsterdam Group, which speaks for a large group of brewers and distillers on the continent, has already spoken out against the European Alcohol Action Plan 2000-2005. Were the WHO’s objectives to be achieved it would mean a severe drop in the profits of the drink industry.

The WHO says that reducing the harm caused by alcohol is one of the greatest public health challenges facing us. “What is needed now is to exercise political will, to mobilise civil society and carry out systematic programmes in every Member State.”

The British Government is a signatory of the Action Plan and will no doubt consider its aims when formulating the national alcohol strategy.

Let there be no moaning at the bar…

says Andrew Varley

The class war is over, said Tony Blair at the Labour Party Conference, and there is little doubt about who won. The pubs of Great Britain once neatly defined their customers’ position on the social scale by a subtly graded hierarchy of bars.

Nowadays, the victory of the liberal middle class is proclaimed by relentlessly egalitarian toping.

According to a survey by the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA), the public bar is fast disappearing. Camra does not share the Prime Minister’s triumphalism but blames the decline on the brewers’ search for increased profit rather than on the end of the class war.

One of the factors in this change is praised by the campaign. Pubs now cater for families much more than in the past and have abandoned the smoke-filled, spit and sawdust image. Nevertheless, Camra says that some pubs risk alienating customers by effectively barring those wearing manual workers’ clothes. Soft drinks bring as much profit as pints of mild.

More than 4,600 pubs in England, Wales, and Scotland were surveyed in the latest Good Beer Guide. In Greater London, it emerges, only 12 per cent of pubs have a public bar and of the 32 most central alehouses, where the beer was of a standard to gain an entry in the Guide, none had a public bar. In Scotland and Wales 36 per cent and in the English west midlands 32 per cent of pubs still had one. Other results were 28 per cent in the east midlands, 26 per cent in the north-west, 22 per cent in the north east, 21 per cent in Yorkshire and the south-east, and 19 per cent in east Anglia and the south-west.

Roger Protz, the editor of the Good Beer Guide, said that the decline had “nothing to do with brewers or pub owners wanting to see stevedores rubbing shoulders with stockbrokers, and everything to do with maximising profits”.

Opening up the interiors of pubs into one bar meant that landlords could charge saloon bar prices. Mr Protz is, of course, primarily concerned with the quality of beer and with its traditional method of production, but he puts his finger on one of the main problems with the retail of alcohol at the moment. Whilst all businesses quite rightly operate to make money, the brewers seem willing to sacrifice everything to this motive. Pubs have often served wider purposes than drinking and, when embedded in the community, performed useful social functions of control. Changing drinking patterns have put an end to this. By far the greatest customer group nowadays consists of young people under 30 and the habit of bingeing is encouraged by the lamentable growth of the theme pub, happy hours, and other gimmicks (see “What’s in a name?”, Alert Issue 1, 1999).

The youth angle is not lost on Mr Protz. He says that the problems are made worse by so many bars aiming at young people’s custom – bars where anyone above 25 was made to feel unwelcome, or, at best, geriatric. “Pub is short for public house,” he said. “All sections of the public should be made to feel welcome. Brewers should preserve public bars for those who wear working clothes or who want to sup a pint of mild a few pennies cheaper than the beers in the lounge.”

The Brewers and Licensed Retailers Association suggested that the days when “working class steelworkers went into one bar, and toffs into another” were over. “There is a much more egalitarian atmosphere now,” said its spokesman, Tim Hampson, disingenuously. “People want to go in family groups, or have a meal. That cuts across the idea of separate bars.” However, Mr Hampson pointed out that anyone “looking for a public bar won’t have to walk past too many pubs to find what they are looking for. The notion that, every time a pub is refurbished, it is gutted and turned into a one bar pub, is quite wrong.”

Whatever the protestations of the brewers, the traditional pub will disappear forever if the drive for profit dictates.

…and at the bar of the house

The government is planning a complete overhaul of the licensing laws and one of the most likely changes will be the disappearance of the old restrictions on opening hours. The familiar cry of “Time, gentlemen, please” will be heard, if at all, when it suits the landlord rather when statute demands.

Anticipating and encouraging the government is an all-party group of MPs and peers which recently added its voice to the call for root and branch reform of “outdated” pub licensing laws in England and Wales. The industry itself, of course, has long campaigned for liberalisation. The group which has not yet been asked its views is the general public.

The parliamentarians involved form the Parliamentary Beer Club, an influential back bench committee which counts 275 MPs and 30 peers among its members and boasts the Speaker of the House of Commons, Betty Boothroyd, as its President. Constituting the biggest single industry group at the Palace of Westminster, it has as secretary, Robert Humphreys, a brewing industry journalist and the director of a public relations firm. Like Mark Anthony offering Caesar a crown, it urges the Home Office to introduce a single, unified, and independent licensing authority to be established to simplify licensing law and procedure. At the moment the complex licensing arrangements, based on the Liquor Licensing Act 1964, are split between local authorities and magistrates.

If the Government follows the urgings of the Beer Club, which it has already all but promised to do, the changes will mean longer and more flexible opening hours for pubs operating in town centres but stricter measures to deal with operators of noisy premises which disturb residential areas.

A further proposal suggests various measures to clamp down on noisy and troublesome licensed premises. The MPs also want to see licences granted to individuals who can transfer them from one pub or bar to another. The individual licences would indicate whether someone was a fit and proper person to run a pub. The licence could be revoked and individual landlords disqualified should they no longer be found to be fit and proper.

Pub premises themselves would have a separate licence, proving the buildings were suitable for the sale of alcohol. The group also demanded more flexible rules relating to children in pubs. The proposals are likely to be incorporated in a Home Office White Paper on licensing reform to be published in the New Year.

The many bars in the Palace of Westminster have always been exempted from opening times set out in the licensing laws.

Medical education in alcohol and alcohol problems

Eurocare has published an important study of under- and post-graduate medical training in alcohol problems. What emerges is the inadequate preparation doctors throughout Europe receive to deal with the results of alcohol abuse. More encouragingly, the experts from a wide range of European countries agree on a series of measures which need to be put in place to remedy the situation.

One of the contributers from the United Kingdom is Professor Brian McAvoy, of the Department of Primary care at Newcastle University Medical School. He writes:

UK primary care perspective

Overview of Educational Programmes

In the UK there has been no centrally funded approach to improve medical education in alcohol problems, unlike in the United States and Australia. Consequently education and training are fragmented and unco-ordinated at all stages of a doctor’s career – undergraduate, postgraduate and continuing medical education (CME). Nationally there is no standardised system for the education and training of general practitioners in relation to prevention, early detection and management of alcohol problems.

Undergraduate

Paton’s questionnaire survey of 26 Medical Schools in 1984 revealed that they all arranged some formal teaching in alcohol but only one used a multidisciplinary approach; one had a regular seminar (run by the Medical Council on Alcoholism) and one had three formal sessions. The rest relied on an ad hoc approach by psychiatrists, physicians, pharmacologists, general practitioners and pathologists. Only occasionally were casualty officers, behavioural scientists or psychologists involved.

Crome’s questionnaire survey in 1987 involved 13 separate departments in 26 Medical Schools. Of the 70 per cent respondents, 54 per cent provided formal teaching (lectures, seminars, symposia). The average time devoted to substance abuse teaching was 14 hours over 5 years, with an average of 6 hours being spent on alcohol – equivalent to 1 minute per week over the entire period of training. Only 21 per cent of clinical and non-clinical departments ensured that students were examined on the topic. Appeals have been made for a flexible ‘core’ curriculum or a set of guidelines ,increasing the emphasis on the importance of alcohol teaching at every opportune stage in the undergraduate experience and integrating such teaching through the curriculum.

It has also been suggested that each Medical School should make a designated teacher responsible for developing integrated teaching in alcohol and that one department, for example general practice, community and family medicine, psychiatry or public health, should take lead responsibility for organising systematic coverage.

Postgraduate

Once again, training and education are fragmented and limited. The various Royal Colleges have produced reports acknowledging the importance of alcohol abuse but it has been reported that a vice-president of the Royal College of Physicians had stated that ‘alcohol is not specifically mentioned in any of the specialty training programmes’. A Diploma in Addiction Behaviour has been developed in London with the aim of ‘training the trainers’. Training and education in relation to prevention, early detection and management of alcohol problems in general practice undoubtedly occurs during the 3 year vocational training period but the nature, amount and timing of this are determined by individual course organisers and trainers.

All the Royal Colleges have been urged to recognise the need to integrate relevant information, skills and assessment into postgraduate courses and examinations.

Continuing Medical Education

As is the case with earlier career experiences, training and education for established practitioners is ad hoc and fragmented. Anderson’s questionnaire study of GPs in Oxfordshire and Berkshire in 1984 found that 66 per cent of respondents reported less than 4 hours total postgraduate training, or clinical supervision on alcohol. A similar study of GPs in Leicestershire, Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire in 1995 showed that this figure had dropped to 42 per cent – still a significant proportion.

The postgraduate education allowance (PGEA) is the principal component of CME for general practitioners but much of the educational activity is ‘didactic, uni-profession and top-down’ and shows little evidence of ‘any convincing benefits for patient care’. The system allows doctors to play to their strengths rather than identify true educational needs, and is therefore unlikely to facilitate improved training and education on alcohol. The recently published Chief Medical Officer’s review of continuing professional development in practice suggests a radical alternative to PGEA – Practice Professional Development Plans (PPDP). These would ‘integrate and improve the educational process, developing the concept of the ‘whole practice’ as a human resource for health care, resembling the health promotion plan in general practice and increasing involvement in the quality development of practices’.

Effective Educational Programmes

There is no shortage of educational materials. The Medical Council on Alcoholism (MCA) is an independent organisation and registered charity which encourages health professionals to identify drinking problems among their patients, and to offer treatment and support.

The MCA organises educational events for student and postgraduate participants, publishes Alcohol and Alcoholism: the International Journal of the MCA, Alcoholism, a quarterly newsletter, and alcohol abuse detection leaflets and drinking diaries designed for use by general practitioners. The MCA has produced a list of 8 learning objectives for medical undergraduates, covering the following areas:

- Alcohol

- Alcohol and the individual

- Cost of alcohol misuse

- Clinical problems

- Psychiatric implication

- Identification and recognition

- Management

- Policies

It also distributes Alcohol and Health. A Handbook for Medical Students to all UK undergraduates and Hazardous Drinking. A Handbook for General Practitioners.

Alcohol Concern, the national agency on alcohol misuse, has produced a National Alcohol Training Strategy for all staff who work with people with alcohol problems. In a joint project involving the Standing Conference on Drug Abuse (SCODA) and Alcohol Concern, the Quality in Alcohol and Drugs Services (QUADS) group has produced a draft quality standards manual for alcohol and drug treatment services. The National Alcohol Training Forum, established by Alcohol Concern, has produced Talking it Through – a national vocational training pack for alcohol counsellor training.

In addition there are generic training packs such as Helping People Change (Health Education Authority) and Skills for Change (World Health Organization).

Finally, the UK Alcohol Forum has recently published Guidelines for the Management of Alcohol Problems in Primary Care and General Psychiatry.

In his review of the rôle and effectiveness of medical education in alcohol, Walsh concluded that ‘with a few exceptions, such as the emphasis on feedback training in skill development, most recommendations about alcohol medical education reflect the findings of process evaluations and/or educator opinion. They are not sufficiently informed by theory or based on studies with rigorous methodologies’.Furthermore it is clear that the education of health care providers will require a complex set of responses. Traditional and limited ‘educational’ responses will not, of themselves, suffice.

Conclusion

Although there is no standardised system for the education and training of primary care workers in relation to prevention, early detection and management of alcohol problems, there are well established educational and training models and materials and explicit competencies and training recommendations available. The proposed changes in the NHS and the review of continuing professional development in general practice offer a unique window of opportunity for advancing this agenda in UK primary care.

“Just too busy”

Since Professor McAvoy wrote his contribution the situation has deteriorated as general practitioners find it increasingly difficult to meet the demands put on them as a result of alcohol abuse. His colleague, Dr Eileen Kaner, and a team of researchers, including Professor McAvoy, from the Department of Primary Health Care at Newcastle University Medical School have produced a study* on behalf of the World Health Organization (WHO) as part of a survey of alcohol problems in 14 countries.

It is estimated that 20 per cent of the workload of GPs arises from the effects of heavy drinking. This is, of course, compounded by the problems which arise from the fact that alcohol abuse creates medical problems for family members. Despite these figures new research shows that GPs feel less confident and less motivated to work with problem drinkers than they did ten years ago.

279 GPs in the East Midlands were interviewed by the researchers and it emerged that only one fifth had any confidence that they could help heavy drinkers reduce their alcohol consumption. Fifty-eight per cent said they could be more effective if given better training and more government support.

72 per cent of the doctors questioned agreed that they were “just too busy dealing with the problems people present with” to use brief alcohol intervention. Of the 14 countries in the WHO study, which included Canada, New Zealand, Thailand and Australia, the UK was second only to Hungary for GP workload. “This means their consultation time is very brief, often about five minutes only,” said Dr Eileen Kaner, one of the researchers from the medical school at Newcastle University. She added that they felt they only had time to deal with immediate symptoms rather than underlying causes. However, Dr Kaner said that effective intervention could cut their workload since problem drinkers were twice as likely as others to present repeatedly with a variety of health problems, ranging from accidental injury to gastro-intestinal complications.

“If GPs had more training they could identify the underlying problems better,” said Dr Kaner. She added that GPs were given “minimal” training about alcohol abuse at both undergraduate and postgraduate level, although its consequences made up a fifth of their workload.

A brief alcohol intervention programme, which takes only a few minutes, has been developed by the WHO and was introduced to the sample group of GPs by Dr Kaner and her fellow researchers. According to Dr Kaner, the programme can help a third of problem drinkers reduce their alcohol intake by a quarter and bring many back to below the danger level. 80 per cent of the doctors surveyed acknowledged that “early intervention for alcohol was proven to be successful.”

The programme involves acknowledging the benefits of alcohol consumption, such as increased sociability, reinforcing safe levels of drinking and identifying problems linked to drinking. As such, of course, its usefulness in the recovery of chronically dependent drinkers is limited and many addiction therapists would argue that a discussion of “benefits” could be counter-productive. However, brief interventions are intended primarily for those “patients identified by screening as drinking above medically recommended levels but with mild or no dependence on alcohol.”

Patients are also shown a graph of alcohol consumption in the UK and their place on it. “It may set them thinking. We also give useful tips for cutting down such as eating before going out and not drinking alcohol when you are thirsty,” said Dr Kaner.

The researchers also provide telephone support for GPs using the brief intervention approach. Their study found 60 per cent would be more involved in treating heavy drinkers were more support provided. Part of the problem, said Dr Kaner, was that many alcohol referral services had been cut.

* Intervention for excessive alcohol consumption in primary health care: attitudes and practices of English general practitioners, Dr Eilenn Kaner et al., Alcohol and Alcoholism, Vol. 34, No. 4, 1999.

New wonder drug?

A pill which is claimed to prevent people drinking to excess has made its appearance on the market.

It is claimed that the development should be able to help a condition which normally responds to drugs only in extreme cases. Alcoholism is usually treated with counselling. Unlike other drug treatments, such as antabuse, which make people physically ill if they drink, the new drug, naltrexone, helps people to control their alcohol habits yet still allows them to imbibe socially.

According to Roger Thomas, a consultant psychiatrist who is promoting the treatment, the pill removes any pleasure in drinking and so destroys craving. The removal of pleasure, of course, is not crucial to the substantial proportion of dependent drinkers who say that they do not actually enjoy the taste of alcohol. It could, on the other hand, be used by binge drinkers to reduce the amount they drink. In the case of dependent drinkers, it could act as a tool in the process of rehabilitation, allowing them time to begin the process of recovery without having to fight a constant craving. Other drugs such as librium are already used in this way. Many experts are cautious about a drug-based approach to addiction. Robert Lefever, the director of the Promis Recovery Centre, said he preferred a non-drug approach. He pointed out that drugs such as antabuse and naltrexone create “dry drunks” who “still have all the behavioural characteristics of an addict. We can prescribe valium and librium to help with withdrawal symptoms but apart from that we do not use drugs.”

Naltrexone, for which an 80 per cent success rate is claimed, works by blocking the effects of alcohol on pleasure receptors in the brain so cravings for it are weakened. Up to now, a small number of people in the United Kingdom have used it at the ContrAl clinics in Cardiff, Bristol, and London.

The drug is not yet licensed in this country, which means that doctors need Home Office permission to prescribe it, and can do so only for named patients. However, the manufacturers hope that naltrexone will soon be available to National Health Service patients. It costs £1,500 for a five-month course which includes 10 counselling sessions. The cost of a course of rehabilitation at a private hospital, such as The Priory, is considerably higher.

Dr Thomas, of Cardiff Community Healthcare Trust, who also works for the ContrAl clinic, said that the drug had to be combined with a psychological approach to deal with the underlying cause of the drinking problem. He said: “This is not a magic treatment. It’s a new approach which has a lot of possibilities. It is not a pill which allows you to drink.” He said it was useful for people who were drinking 50 or more units a week.

Professor Brian McAvoy, of the Department of Primary Care at Newcastle University Medical School, agreed that naltrexone “was not a wonder drug but that it benefits dependent drinkers as long as it is used along with social and psychological support.” Professor McAvoy, who has observed the use of naltrexone in Australia where it is a licensed drug, said that it would be interesting to see the results of its use with dependent drinkers recruited through General Practice rather than specialist addiction units.

A study of the drug’s use in America, which looked at more than 3,000 patients, showed that naltrexone was a safe and effective treatment for alcohol dependence as part of a counselling programme. The average number of drinks per week fell from 57 to four and the main side effect was nausea. The considerable press interest in the drug is an echo of previous sensational stories of wonder drugs which were heralded as the answer to dependent drinking and so it is important to keep in mind the fact that naltrexone’s benefit comes when it is used alongside counselling and other forms of psychological therapy.

The writer Catherine Grace was the first person to take the drug in this country. She began drinking as much as three bottles of wine a night after the breakdown of her marriage. She tried Alcoholics Anonymous but relapsed after three months.

After taking the drug for a few weeks she gradually started to lose the desire to drink. She now only drinks at social functions and does not enjoy more than two drinks. She said: “Now when I drink I do not get the buzz. Instead I get a buzz from salsa dancing and keeping fit.”

Wine, women and Sam

A Life of James Boswell by Peter Martin, Weidenfeld and Nicolson

It could be said that writing a biography of James Boswell is like painting a portrait of Rembrandt: the man has already done it rather well himself.

Peter Martin has accepted the risk of comparison with his subject and he faces the challenge with confidence and style. Whilst he has avoided the pitfalls either of being a mouthpiece for Boswell’s journal, he does not attempt to establish his independence by avoiding lengthy quotation. He has, for example, the good sense to give us the splendid account of the seduction of Louisa in Boswell’s own words. All in all Mr Martin has produced a highly readable and amusing narrative. Not everything is quite right, however, and there are times when it seems that he has little grasp of the period. He takes some time to make up his mind as to whether there is a Countess or a Duchess of Northumberland. In fact, the same lady was both (she was the Percy; her husband, a baronet called Smithson, who sensitively changed his name, was created a duke in 1766). More seriously, his detailed account of Boswell’s visit in 1766 to Brunswick, Prussia, and a number of minor courts, betrays almost total confusion over German history. He gives a sketchy description of the Holy Roman Empire (with a curious reference to Czechoslovakia’s boundaries in 1935) and tells us ludicrously that Frederick William II of Prussia (reigned 1786-1797, by the way) was Emperor. The index describes this same king as “The Great”. Frederick II, his uncle, is usually given that soubriquet and was indeed king when Boswell was in Germany. Frederick was the best known misogynistic homosexual of the eighteenth century and might have been surprised to hear that he had a son to whom, according to Mr Martin, Boswell was presented.

The laziness and cupidity of publishers is becoming increasingly tiresome and, I hope, counter-productive. Should not someone have saved Mr Martin from these embarrassing gaffes? Was there not a single editor at Weidenfeld and Nicolson capable of spotting that Lord Monboddo, a fellow judge of Boswell’s father, Lord Auchinleck, is referred to as Mondobbo on half the occasions he is mentioned, or that the eminent doctor, Sir John Pringle, is gratuitously awarded a peerage? These are not trivialities. They leave the reader with a problem of trust. How far can he believe any of the author’s assertions?

Mr Martin is on surer ground when he is dealing with literary London and Boswell’s relationship with Samuel Johnson and he manages to give us a feel for Edinburgh at the time when it was emerging from a squalid provinciality into the Athens of the North. More than this, he conveys the complexity of Boswell’s character and the factors which combined to create a driven and tortured personality. Mr Martin wants to rescue Boswell from his reputation as a buffoon. So well ingrained is this impression that it might seem an impossible task. Macaulay’s judgement that “if he had not been a great fool, he would never have been a great writer” was accepted wisdom for years. There is no doubt that many contemporaries mocked him. He was often the butt of Dr Johnson himself and we know this because he gleefully records his own humiliations. His solipsistic musings verge on the absurd more often than not. However, he was loved by almost everyone who knew him. His company and conversation was welcomed and sought by a wide variety of eminent men: Johnson himself, David Garrick, Edmund Burke, Oliver Goldsmith, John Wilkes, David Hume, the Duke of Queensberry, Lord Bute, Lord Pembroke, General Burgoyne. During his visit to Corsica, he won the confidence and friendship of the rebel leader Paoli, whose cause he vigorously championed at home, and, in the French controlled part of the island, charmed the Governor, the urbane Comte de Marbeuf, who as a matter of interest, was the lover of Laetizia Bonaparte and probably the father of her son Louis, but not, as is sometimes asserted, of Napoleon himself. Boswell had a talent for ingratiating himself with luminaries: by any standards Voltaire and Rousseau were A-list celebrities and they both liked him, allowed him unprecedented access, and maintained contact. The things which marked Boswell out from armies of fame groupies, the sort who today write in colour supplements, were his engaging personality, his clubbability, his sharp intellect, and his critical acumen. All these qualities he had in abundance. He was also a drunk, a sexual profligate, and a depressive.

Boswell’s depression, a condition which was common in his family, was much exacerbated by his Presbyterian upbringing. His father was cold and distant; his mother loving but devoted to Calvinistic gloom. Prospects of an afterlife and the possibility of spending it among the damned were preoccupations which recurred throughout his life. He nearly escaped, fleeing to London, and instruction in the Catholic Faith. Fashionable Society and tarts proved too powerful a distraction. Although he did have the privilege of kissing the Pope’s foot during his visit to Rome, in the end he made do with the arid grandeur of latitudinarian Anglicanism. He was always being pulled both ways: restraint and abandonment; order and chaos; his wife and the whores of St James’; the measured, intellectual pleasures of Johnson’s conversation and the stupor of solitary drinking. When he drank, he whored. When he whored, he despised himself and plunged into melancholy. When he was “hypochondriak”, a contemporary name for the condition, he drank. Even in an age when venereal disease was routine and when an upright figure like Lord Auchinleck could accept that a dose of the pox was part of a young gentleman’s experience, Boswell must have held some kind of record for the number of times he suffered from gonorrhoea. Alcohol nearly always played its part, although, of course, Boswell was a man of huge sexual appetite and needed little encouragement. “By 17 April…he was free of the infection, but in June he did exactly the same thing, with worse results, spending the night at a brothel with a whore…after an evening of heavy drinking.” This was a story repeated again and again. Although he did remain largely free from infection once married to the long-suffering Margaret, he did not remain faithful (although he rationalised that whores did not count) and was occasionally violent when drunk.

An indication of his good qualities was that his friends did not desert him. Some attempted to help him mend his ways. Dr Johnson was full of good advice on the avoidance of overindulgence. Paoli induced him to take an oath to give up drink for a year, an oath which, in the way of these things, led to a spectacular binge once broken.