In this month’s alert

Sad day dawns

24 hour licensing finally became a reality for England and Wales at midnight 24 November 2005, the so-called Second Appointed Day (SAD). Ironically, in view of repeated claims by government ministers that Scotland’s experience proves the case for licensing liberalisation, 24 hour licensing arrived south of the border just at the time it was being ruled against the public interest by the Scottish Parliament.

Secretary of State Tessa Jowell said: “The vast majority of adults drink alcohol. Most people live within walking distance of a pub or bar. Alcohol is part of our national life.

“That’s why these new laws are so important. For too long we have allowed a small minority to rule the streets at night and our main recourse has been a national curfew. This was unfair in principle and wrong in practice.

“From today we have got our priorities right. Yobbish behaviour will be cracked down on and adults will be treated like grown ups.

“Getting the national relationship with alcohol right is a massive undertaking. This is only the start, but it’s a vital first step.

“The one thing this act isn’t about is encouraging 24 hour drinking. Indications are that one half of one percent of licensees have applied for a 24 hour licence and many of them do not intend to use it regularly.”

Home Secretary Charles Clarke said: “We are determined to tackle alcohol related violence and anti-social behaviour in all its forms and crack down on those who encourage it by irresponsible retailing.

“We believe that the Licensing Act will help to reduce alcohol fuelled disorder by providing the police with new tough powers to close down problem bars and increase penalties for premises that sell to underage drinkers, while at the same time ensuring that the law abiding majority can enjoy a drink when they wish.”

Speaking for the British Beer and Pub Association, Mark Hastings also welcomed the new regime, revealing that the system of permitted hours was in fact the sole cause of binge drinking. Speaking on ITV news he said: “In the rest of the world where we have flexible licensing laws we don’t have binge drinking. In this country, where we have lived for nearly a hundred years with very rigid licensing laws, we do have binge drinking.”

However, it soon became clear how isolated the Government and its partners in the alcohol industry had become from mainstream opinion. SAD was greeted by saturation media coverage, most of it sceptical or hostile, and a chorus of negative comment from the other political parties, professional groups such as police and doctors, local residents and the public at large.

Public opposition

ITV revealed the results of its opinion poll showing a 2:1 majority against 24 hour licensing, almost exactly the same proportion as had been reported by previous polls beginning in 2000.

Residents’ groups up and down the country expressed their anxieties about the new legislation. Speaking for Open all Hours?, Matthew Bennett said that the Government had wasted the opportunity of tackling the binge drinking culture and that the new legislation would make life worse for town centre residents. He called for early changes to the legislation (see below).

Police concerns

For the police, Commander Chris Allison of the Metropolitan Police warned how extending opening hours in some pubs and clubs could lead to an increase in drink fuelled violence and anti-social behaviour.

John Yates, the Association of Chief Police Officers’ (ACPO) expert on sexual offences, warned that the new Act could result in more cases of rape and increased allegations of rape. He said: “Drinking is a real issue. Forget Rohypnol [the date rape drug], the biggest single factor in terms of drugs and rape is alcohol. Men, I suspect, think that they can get away with rape; that they have a one in 20 chance of being convicted. Rapists are clever. They have changed their behaviour, they are targeting nightclubs where young girls have been drinking.”

Lord John Stevens, the former Metropolitan Police Commissioner, had earlier launched a scathing attack on the new licensing laws saying he could not understand why the Government had introduced them in the face of police opposition. Speaking on BBC Radio Four’s ‘Any Questions’, he stated: “If you need police officers on the street as you will do at three, four, five in the morning, to look after people who are completely drunk, out of their minds, then you are going to have to take police officers away from other duties that they’d be doing during the day.”

The current Commissioner, Sir Ian Blair, said that he saw “anyone who wants a drink at four in the morning as a special interest group and those making profits out of it are going to have to pay.”

Fears about overstretched resources were shared by Jan Berry, chair of the Police Federation. She did not believe that extended drinking hours would bring about a change in the binge drinking culture but would require additional police resources. ACPO had previously issued a statement expressing concern “about extending the hours that people can drink given the culture of excessive drinking that already pervades our society. Over the last few years, we have already seen premises being allowed to open later and later. At the same time we have seen a sharp increase in alcohol fuelled violence and antisocial behaviour…”

Medical fears: ’Licence to Kill’

A range of medical bodies attacked the new Act. For the Royal College of Physicians, Professor Ian Gilmore said: “The Government has ignored expert advice from around the world that the main drivers of alcohol-fuelled damage are price and availability, and so we fear that relaxation of licensing laws will lead to more drunkenness, alcohol-related illness and social order problems. The UK’s millenium-old traditions of binge drinking are not suddenly going to change overnight into continental style moderate consumption. We expect our A&E units will feel the pressure, and the long-term effects will be damaging to the health of our young people.

Recent initiatives from alcohol retailers, such as stopping serving the under-age or drunk, have clearly failed. We call on the Government to put a 1% levy on the drink industry’s £30 billion turnover so that independent research can help provide some real answers to this country’s rising tide of alcohol misuse.”

The British Liver Trust (BLT) warned that the new Act will mean more early deaths from chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, and called for an urgent alcohol-related prevention campaign.

“How can licensing laws permitting 24-hour drinking stand shoulder to shoulder with Government initiatives to promote healthy living?’ asked BLT Chief Executive Alison Rogers. ‘This change in the law is causing grave concern among hepatologists and all those working to stem the epidemic in liver disease.”

Professor Roger Williams, the liver specialist who treated footballer George Best in his final illness, said 24-hour drinkingreflected a society that was “falling apart”. He said on Sky TV: “I see liver disease all around increasing. I just can’t accept that any measure that results in an increase in alcohol consumption in this country as a whole can be justified.

“I don’t think there is any evidence that lengthening the periods of drinking in this country will lead to less alcohol consumption. It will lead to more. There is only one way of reducing alcohol consumption, that’s increasing the price.’’

The British Association for Emergency Medicine warned that the licensing changes could create even more problems in Accident and Emergency Units which were already operating under extreme pressure.

The Chartered Institute for Environmental Health Officers also warned that the new Act would place a huge strain on them and that public health could suffer. Environmental Health Officers have an important role in operating and monitoring the new legislation and the Institute expressed fears that they are not adequately resourced to carry out their additional responsibilities.

Local taxpayers to subsidise pubs

Council tax will have to rise to pay for the new licensing regime, according to local authorities. A survey by the Local Government Association found that virtually every council reported that, contrary to repeated Government promises, the new licensing fees were insufficient to cover the costs of implementing and administering the new system. The London Borough of Camden, one of whose residents is Tessa Jowell, reported a £1.1 million deficit. The neighbouring Borough of Westminster reported being £3 million in the red, and estimated that in the next financial year the deficit will increase to £4 million. Calculations suggested that, overall, local authorities in England and Wales were facing a £71 million shortfall.

Party political opposition

The opposition parties launched vigorous attacks on the new Act. Commenting on the financial deficit, Conservative Shadow Local Government and Communities Secretary, Caroline Spelman said: “Labour’s reckless new licensing laws are yet another example of expensive burdens imposed on councils by Whitehall, with council tax payers left to foot the bill. With alcohol soon to be plied into the early hours every day, local people have every right to feel extremely angry – their wishes about late night drinking are being ignored, and now they are expected to pay for the consequences of binge drinking.”

Dr Dai Lloyd, Plaid Cymru’s shadow Local Government Minister, broadened the attack. He said: “There are going to be serious financial costs resulting from the new laws. As well as higher costs for the police and NHS in dealing with the aftermath of later opening, we now hear that council tax payers are going to have to pay out for this ill thought out law.”

Dr Dai Lloyd added: “24 hr drinking is going to have major consequences for people in Wales. It is obviously going to lead to more alcohol consumption. This will mean more alcohol related violence and more alcohol related illnesses such as liver cirrhosis.”

24 hour drinking will not increase crime – or will it?

Opposition politicians were particularly incensed by statements by James Purnell, the licensing minister, and Paul Goggins, the Home Office minister, that the crime figures would probably rise after the Act came into force, but who then went on to explain that what they really meant was that, while arrests would increase as a result of greater police activity, the actual level of crime would fall.

This argument did not convince the Liberal Democrat Don Foster, who said: “The Government’s argument that we should expect more alcohol offences only as a result of the new police powers in the Licensing Act doesn’t stack up. All the new powers to be introduced by the Act are to tackle rogue pubs, not individuals. If anything, these powers should reduce, not increase, overall alcohol offence rates. These last minute spurious arguments smack of desperation. Ministers should have swallowed their pride and stopped 24 hour drinking before it was too late.”

The Liberal Democrats also released figures showing what they claimed was a 20 per cent increase in alcohol-related violent crime in the last two years. Don Foster added: “These figures provide further evidence that binge drinking is out of control. International research evidence shows that increasing the availability of alcohol will make matters worse. So it’s clear that the new Licensing Act will lead to a further increase in these figures with yet more people becoming the victims of alcohol-fuelled violence.”

Open all hours?

Residents braced for Government’s ‘broken promises’

The licensing shake-up marked a huge missed opportunity to make a dent in Britain’s alcohol problems, the residents’ campaign group Open All Hours? said in a statement. While the Act could have promoted greater powers for residents and a coherent local approach, it instead promises to create a weak, patchy, reactive system that does little to help those living with the consequences of Britain’s binge drinking culture.

Matthew Bennett, chairman of OAH?, said: “In a climate of massive public and political concern over binge-drinking, this Government had a chance to respond positively and think again about the detail of the way they are changing the licensing laws to ensure that they clearly act in a way that changes British drinking culture for the better – but this is a chance that they have spectacularly failed to take. The promise was to empower residents where they have problems but, in reality, they have simply burdened them with a one-sided system that already shows signs that it isn’t going to work. We are starting to see that even where licensing authorities have turned applications down or placed other restrictions on licensees, magistrates appear to be overturning many of those decisions on appeal or the trade just comes back with another application.”

Based on a combination of their own experiences and the international evidence, OAH? believed that the forthcoming review of the Statutory Guidance to the Licensing Act should make at least three key changes as a matter of urgency:

1. Remove from the Guidance the strong recommendation to councils to grant longer hours as a method of cutting disorder. The evidence for this was extremely tenuous. Instead, emphasis should be placed on tailoring opening hours and activities to achieving the licensing objectives.

2. Make sure residents were not bizarrely excluded from having a say by making sure that anyone with a ‘real and material interest’ can object, rather than restricting the right to be heard to those who live `in the vicinity’ of a particular pub or club.

3. Where there was already evidence of general late night crime and disorder in any area, licensing authorities should be allowed to place limits on later hours across the board until antisocial behaviour in that area had been brought under control.

Matthew Bennett added, “Despite the furore in the media for many months, it is still unclear if the Government has any idea of what sort of late night economy they want to create. While the Government may not want to acknowledge that the problems are continuing, it is crucial that the review of the Guidance recognises the everyday experiences of residents, the police and health professionals throughout Britain and responds much more positively to those concerns.”

Precise estimates vary of the number of pubs which have obtained extra trading hours, but the consensus is around one third.A BBC survey found:

- 60,326 extensions in hours for selling alcohol – but this figure and the others below were derived from a survey of 301 of the 375 authorities, so the final figure will be higher, probably around 70,000.

- 1,121 establishments will have 24-hour licences and of these 359 are pubs or clubs. 250 supermarkets have obtained licences to sell alcohol round the clock.

- South East England has the largest number of approved licences – 10,500.

- Some 5,200 extensions have been approved in London – but just 14 pubs or clubs can open for 24 hours.

- More than 150 pubs or clubs in the south and west of England gained 24-hour licences, with just eight in the West Midlands.

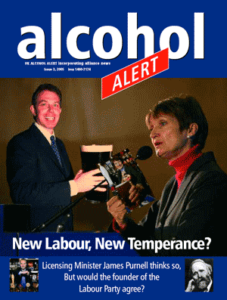

Labouring under the influence

Andrew McNeil writes: The Labour Government’s introduction of 24 hour licensing, together with its original plan for a similar free-for-all in relation to gambling, has led some commentators to accuse the party not so much of deserting its traditional moral outlook as deliberately trashing it. The accusation was given particular force by the now notorious text message “Don’t give a XXXX for last orders? Vote Labour” sent out during the 2001 general election campaign.

Nick Cohen in the Observer has complained that Labour’s Methodist conscience has been replaced by greed and insobriety. Melanie Phillips, having asked rhetorically who could have imagined a Labour cabinet minister (Tessa Jowell) posing beside a roulette table as if she were placing a bet in order to launch a casino culture in Britain, and claiming that this was an example of `social reform’, went on to lambast the Labour government for undoing the very social improvements that its Victorian ancestors worked so hard to achieve.

“For the Victorian reformers, the essence of being a progressive was to encourage people away from sexual promiscuity and the gin palaces. Indeed, the only reason the British public house became a relatively civilised place was because the Victorians introduced licensing laws which stopped unlimited drinking, which was perceived to be a major cause of drunkenness and disorder.

Now we are undoing that very reform. Instead of being progressive, we are going backwards. Rather than promoting self control and continent behaviour, we are encouraging unlimited licence.”

The non-conformist conscience

Famously, Methodism was a stronger influence than Marxism on the early Labour Party, and temperance, as one important aspect of the non-conformist conscience, was indeed powerfully represented in Labour ranks.

In the late Victorian era, professional labour leaders were convinced of the need for the working class to be industrious, thrifty and sober, as continued intemperance would stifle the opportunities and aspirations of the emerging labour movement. This perceived symbiosis between social improvement and personal virtue was expressed in religious as well as secular terms. Alfred Salter, a noted advocate of Christian Socialism said “If we are going to create a new social order wherein dwelleth righteousness, we can only create such a state through the agency of righteous men and women”, and for Salter and those who thought like him, strong drink did not promote righteousness.

Keir Hardie, the founder of the Labour Party, was a temperance man, as was his colleague Phillip Snowden. Snowden was the author of Socialism and the Drink Question and declared that alcohol “is an aggravation of every social evil, and, in a great many cases, the prime cause of industrial misery and degradation. Universal temperance would undoubtedly bring incalculable benefits and blessings.” In the 1920’s, Labour politicians were very conscious of the Party’s non-conformist origins and heritage. In 1929, Arthur Henderson, the secretary of the Party, wrote: “The political Labour movement, which developed out of the Trade Union Movement, and drew the majority of its early Parliamentary leaders from it, received much of its driving force and inspiration from radical non-conformity. It is a demonstrable fact that the bulk of the members of the Parliamentary Labour Party at any given time during the last twenty-five years had graduated into their wider sphere of activity via the Sunday School, the Bible Class, the temperance society or the pulpit.”

Yet strong though the links were between Labour and temperance, there was never a single view. How could there be, when masses of workers, and potential Labour voters, were dependent on drink and pubs for their social life? The nonconformist wing of the Labour Party saw alcohol as the enemy of working class improvement, but in 1924 a middle class Marxist like E. Belfort Bax could write in ‘The Labour Party and Puritanism’: “Even in their attempts to form Labour Clubs for social intercourse the same puritanical intolerance of alcoholic liquors is observable. Verily we need, not a Labour, but a Socialist Conference to decide on what is consistent with the Socialist outlook on life and what is not, and in so doing to sift the pure grain of socialism from the surviving chaff of bourgeois Puritanism….”

The period leading up to the turn of the 20th century was the highpoint of the alliance between Labour and temperance: during the early part of the new century it started to splinter. By the time Arthur Henderson was writing of Labour’s non-conformist heritage, the Party had already dropped its Committee on Temperance.

Historians have suggested that by the time Ramsey McDonald became the first Labour Prime Minister in 1924 there were three schools of thought evident in the Party in regard to alcohol. A faction still argued for total abstinence; a second group held that drinking and drinking establishments were an integral part of working class life, and the third urged that the Party should seek the nationalisation of the alcohol industry. This last view was put forward in a Party policy statement in 1923:

“It must be recognised, even by those holding diverse views as to the plan or method of temperance reform, that the enormous vested interest in the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages constitutes, in itself, a serious obstacle to every kind of reform. It can be forcibly argued that no effective temperance reform is possible so long as so great an interest as the liquor interest is in private hands. If, therefore, we do nothing on this point, we must look forward to a long period during which the efforts of private persons who desire any kind of temperance reform will be opposed by the money and organisation of one of the most formidable vested interests in the country. In fact, the political power of the ‘trade’ is now a standing menace to promoters of reform of any kind in Parliament or at Parliamentary elections.”

Also affecting Labour’s attitude to the alcohol question was a longstanding debate between, on the one side, temperance advocates, who attributed much poverty and other social problems to the depredations of the trade in alcohol, and on the other, socialist reformers who believed that it was the bad social conditions created by an unjust social order that were the cause of intemperance.

While this debate was never finally resolved, and Labour’s alliance with temperance, certainly in the restricted, total abstinence sense of the term, should not be exaggerated, old Labour was firmly committed to ‘temperance reform’ in a broader sense and to the support of what are nowadays described as strong alcohol control policies. To that extent, new Labour is indeed vulnerable to the accusation that it has more or less wholly abandoned its previous outlook, and is now pursuing policies diametrically opposed to those the Party favoured in the past.

While the temperance influence waned over the years, a residual non-conformist conscience was evident even up to the late 1980’s in the then Labour opposition’s response to the, by New Labour’s standards, extremely modest licensing reforms contained in the Conservative Government’s 1988 Licensing Act. Until 1997, it was unthinkable that, in government, Labour would itself introduce 24-hour licensing, let alone attack, amongst others, its own founders, as Tessa Jowell has recently done, for “strict Edwardian laws (denying) children real access to the world of pubs..”, which, according to Ms Jowell, “made a rod for our own backs”.

It is difficult to be sure of the nature of the thinking that underlies this determination to encourage children into bars, but whatever it is, it would be anathema to the early Labour leaders. They did indeed support the measures Ms Jowell dislikes, and did so in order to protect children from the abuses to which they were subject during the Victorian era. The early Labour leaders might also wish to point out that the measures of which Ms. Jowell complains did in fact succeed in preventing for most of the 20th century the problems of underage drinking and teenage alcohol abuse that have now become so conspicuous, as the Edwardian controls have come to be seen as outdated relics of a bygone age, and steadily whittled away.

New Labour, New temperance?

New Labour might, of course, wish to claim that it has not abandoned the Party’s historic commitment to ‘temperance reform’, merely adapted it to current social realities which are wholly unlike those known to its predecessors. Has not New Labour devised a National Alcohol Harm Reduction Strategy?

The persuasiveness of this claim depends on the view taken of the circumstances of the Strategy’s preparation as well as its content. Arguably, the pressure to produce an Alcohol Harm Reduction Strategy of some kind was becoming irresistible as national alcohol consumption and the health and social harm caused by alcohol, continued to climb steeply under Labour.

Since Labour came to power, total alcohol consumption in the UK has climbed to levels not seen for generations. The steady reduction in drink drive deaths has been halted and put into reverse, and the total number of deaths caused by alcohol is accelerating. Hospital admissions for alcoholic liver disease have virtually doubled since New Labour took office.

Then there is the question of the content of the Alcohol Strategy and, in particular, the fact that its basis is a partnership between Government and the alcohol industry, the very vested interest New Labour’s predecessors regarded as blocking any prospect of progress.

The new Licensing Act is presented as a major component of the Alcohol Strategy, yet it was devised at the behest of the alcohol industry, principally the big pub companies and the British Beer and Pub Association (BBPA). Indeed, some meetings of the Licensing Advisory Group set up by the Government to advise on the legislation actually took place at the headquarters of the BBPA.

It is generally accepted that the Alcohol Strategy was especially adapted to accommodate the views and interests of the alcohol industry. Here, as also in the Government’s White Paper on public health, the only ‘alcohol misuse’ agency deemed worthy of mention was the alcohol industry’s Portman Group, an important part of the function of which is to lobby against alcohol control measures such as alcohol taxes and other controls on alcohol availability, the very measures which the research evidence suggests are the most effective in reducing alcohol related harm.

One commentator, Professor Robin Room, observed: “Having offered its arguments for steering away from price and availability (of alcohol), the Strategy continues: ‘So we believe that a more effective strategy would be to provide the (alcohol) industry with further opportunities to work in partnership with the government to reduce alcohol-related harm.’ No evidence is offered of why this would be ‘a more effective strategy’; again, the evaluation research literature would not support the belief. My reading of this sentence is that it must have been written with a wink, essentially as a statement that ‘our political masters decided that the Strategy’s approach would be to work with the alcohol industry, and vetoed recommendations on matters like price and availability which would upset the industry.”

Similarly, when in 2002 the Government announced that it was reneging on its proposal to lower the drink drive limit to 50mg%, a House of Lords committee noted that the Government’s position “coincides with that of the alcohol industry but is opposed by local authorities, the police, the British Medical Association, the Automobile Association, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents, the Transport Research Laboratory and the Parliamentary Advisory Committee for Transport Safety.”

Recently, Tessa Jowell repudiated as ‘stupid’ the ‘Don’t give a XXXX..’ text message, saying that “It portrayed what is in fact a serious piece of legislation intended to improve quality of life and curb crime as some kind of advert for hedonism.”

Labour’s problem is that disowning a slogan, however belatedly, is likely to prove a good deal easier than disowning the consequences of its policies. Few people other than Ms Jowell and the British Beer and Pub Association believe, or bother to pretend they do, that the new Licensing Act will improve anything other than the big pub companies’ profits. As it emerges that, in anticipation of the new Act, managers of pubs “are being offered bonuses worth up to £20,000 a year if they beat targets as the industry moves to exploit Britain’s binge drinking culture”, it looks even more probable that the new licensing laws will exacerbate problems of binge drinking, crime and disorder rather than solve them.

Old Labour’s policies may have been good or bad, right or wrong, but at least it was clear what kind of social values underlay them. They were motivated by a desire to bring about social improvements, particularly to the lives of working people, by tackling drunkenness and the poverty and disease that it could cause, to protect children, and to bring a potentially dangerous drink trade under public control. With the full effects of 24-hour licensing still to be seen, the values and principles that inspire New Labour are not perhaps so obvious.

Alcohol nation

Action on Addiction has launched a campaign supported by alcohol experts from across the UK to highlight the consequences to the nation’s health of drinking too much alcohol, and to work with the Government to develop evidence-based policies to counter these harms

I’m 30 years old and have been a regular binge drinker since I was about 16. I typically go out every Friday and Saturday night and drink till I can’t drink any more, either because I pass out, or because the club is shutting. I usually also go out and have a couple of bottles of wine with a friend during the week.

I recently went for a health check as I’d been feeling a bit under the weather, and they told me I had alcoholic hepatitis, and was on the way to cirrhosis. I now have to give up drinking, and might even need a liver transplant one day. I wish I’d known this could happen to me – I thought liver disease was something that happened to old men.

Rebecca, 30

Action on Addiction is asking the Government to:

1. Provide long-term funding for an alcohol worker in every hospital.

Up to a third of all admissions to A&E are alcohol related. The health costs of alcohol problems are estimated at £1.7 billion per year. In the handful of hospitals where there is already an alcohol worker, they provide an invaluable service, identifying problems in patients on the wards, giving training to all frontline staff on how to deal with alcohol issues and delivering brief interventions to patients in A&E with alcohol-related conditions.

Research has shown that brief interventions in A&E are very effective in reducing hazardous drinking in non-dependent drinkers. If this was implemented it could represent a considerable saving to the NHS, through bringing down the current costs of alcohol problems, in addition to other benefits such as reduced waiting lists.

2. Implement a tax based on the percentage of alcohol in a drink.

The price of alcohol, relative to average income, has halved since 1965, coinciding with a massive rise in consumption. Research in Australia demonstrated that when a tax based on the percentage of alcohol in drinks was introduced, combined with the launch of low alcohol alternatives by the alcohol industry, people switched to the lower alcohol alternative because it was cheaper. As a general rule, the higher the price of alcohol relative to income, the less the nation as a whole drinks. Alcoholics and heavy drinkers tend to be just as responsive to changes in the price of alcohol as moderate drinkers.

3. Fund a research initiative working with the alcohol

industry on the effectiveness of warning labels on bottles and

advertising.

There is mixed evidence from a number of other countries on the effectiveness of warning labels on alcoholic beverages. However, the messages tested have been fairly weak, and no research of this kind has been tried in the UK. The Department of Health is already discussing labelling with the beverage alcohol industry in the context of units and safe limits. Action on Addiction would like them to go a step further and test key health warning messages. With the ‘Choosing Health’ White Paper prioritising raising awareness of the contribution of alcohol to obesity, and the FSA investigation of the effects of food labelling, we recommend that the alcohol industry follow suit in what could be an effective tool to influence behavioural change. These changes could have a significant impact in a short space of time.

Alcohol treatment services expanded

The Department of Health has published a programme of improvement for alcohol treatment services, which includes £3.2 million for projects that catch the early stages of alcohol related problems.

The funding is planned for helping to identify people who might be damaging their health with alcohol. The Alcohol Needs Assessment Research Project, carried out as part of the exercise, estimates that there are 1.1 million adults with alcohol dependence in the UK and that eight million people drink above recommended limits.

The Needs Assessment Project also provides the most accurate picture yet obtained of the demands placed on treatment services and the amount of funding ploughed into them. It appears that around 63,000 alcohol dependent people receive specialist treatment each year, and the annual spend on specialist alcohol treatment is £217 million. There are approximately 4,250 whole time equivalent personnel working in specialist alcohol agencies in England.

Launching the initiative, Public Health Minister Caroline Flint said: “Alcohol misuse has a devastating effect on millions of lives every year. The publication of the alcohol treatment audit gives us, for the first time, a comprehensive understanding of the trends of alcohol misuse and service provision available across the country. We have found that treatment does make a real difference. By helping 10% of dependent drinkers to give up alcohol, we can save the public sector up to £156 million each year.”

To improve services, £3.2 million has been allocated to new initiatives which will help with identification and early intervention for people whose use of alcohol may be damaging their health. These projects will take place in different health and criminal justice settings.

They will be monitored and could provide the evidence needed to set up similar projects elsewhere. It is expected that by identifying the problem as early as possible, it will help avoid the serious damage that alcohol dependency has on the health of the individual as well as its negative effects on their relatives and society as a whole.

Also being developed as part of the Programme of Improvement are tools designed to help Primary Care Trusts improve the services for problem drinkers by providing practical steps and best practice examples of delivering treatment to those who need it.

From January 2006, the Department of Health will hold nineregional conferences to discuss with health providers how to use the Programme of Improvement to best effect in each area.

Alcohol needs assessment

The Alcohol Needs Assessment Research Project (ANARP) provides the first detailed national picture of the need for treatment and the availability of provision. The research was carried out by a consortium of organizations led by Professor Colin Drummond of St. George’s Hospital.

The main findings are:

- A high level of need across categories of drinkers. 38% of men and 16% of women (age 16–64) have an alcohol use disorder (26% overall), which is equivalent to approximately 8.2 million people in England.

- There are 21% of men and 9% of women who are binge drinkers. There is a considerable overlap between drinking above ‘sensible’ daily benchmarks and ‘sensible’ weekly benchmarks for both men and women.

- The prevalence of alcohol dependence overall was 3.6%, with 6% of men and 2% of women meeting these criteria nationally. This equates to 1.1 million people with alcohol dependence nationally.

- There was a decline in all alcohol use disorders with age.

- In relation to ethnicity, black and minority ethnic groups have a considerably lower prevalence of hazardous/harmful alcohol use but a similar prevalence of alcohol dependence compared with the white population.

- There is considerable regional variation in the levels of alcohol related need. The prevalence of hazardous/ harmful drinking varied across regions from 18% to 29%, whilst alcohol dependence varied between regions ranging from 1.6% to 5.2%.

In relation to the utilisation of alcohol services, the study found:

- Although the majority (71%) of patients with an alcohol use disorder identified by GPs were felt to need qualitative research suggested that many were not referred because of two main factors: perceived difficulties in access, with waiting lists for specialist treatment being the main reason given; and patient preference not to engage in specialist treatment.

- Both the qualitative and quantitative research identified a high level of satisfaction with specialist services once access was achieved.

- Drug Action Teams (DATs) receive funding from a range of sources including primary care trusts, local authorities and charitable funds. In the quantitative survey of DAT professionals, 86% of respondents said that their alcohol treatment budgets are much lower than drug budgets.

- Although not required to do so, 60% of DATs surveyed reported having a local alcohol strategy in place.

- In the qualitative research with DAT professionals, this group was aware of a ‘very large gap’ between the provision of alcohol treatment and need or demand, however it is expressed.

- The specialist alcohol agency survey successfully identified 696 agencies providing specialist alcohol interventions. This research has revealed 43% more agencies than identified in previous research.

- The mapping exercise identified considerable regional variation in the number of agencies, with London having the largest number of agencies and the North East the fewest.

- The largest proportion of referrals to alcohol agencies are self referrals (36%) followed by GP/primary care referrals (24%).

- The estimated annual spend on specialist alcohol treatment is £217 million. The number of whole time equivalent personnel working in specialist alcohol agencies across England is approximately 4,250.

- The average waiting time for assessment was 4.6 weeks. The shortest average wait fora region was 3.3 weeks and the longest wait was 6.5 weeks.

- The gap analysis estimated the number of alcohol dependent individuals accessing treatment per annum is approximately 63,000, providing a Prevalence Service Utilisation Ratio (PSUR) of 18 (5.6% of the in need alcohol dependent population accessing alcohol treatment per annum or 1 in 18).

The art of binge drinking

The British culture of binge drinking received artistic recognition in a state-funded art show in which the female performance artist consumed large quantities of beer and then attempted to walk along a balancing beam two feet off the ground.

The Japanese artist Tomoko Takahashi, a former Turner Prize nominee, described her work as a comment “on the availability and use of mass-produced products”. She was awarded a £5,000 grant to put on her one-woman show at the Government-funded Chapter Arts Centre in Canton, Cardiff. Audiences saw Miss Takahashi arrive on stage in high heels and a smart black business suit. For the next three hours, they watched her drink numerous bottles of lager while periodically lurching towards the beam and seeing how much of it she could negotiate before falling off.

Unfortunately, some in South Wales showed themselves unable to appreciate the work’s aesthetic qualities by complaining that it was no more than an exhortation to binge drink.

“This is stupid and dangerous and sends out the message that binge drinking is OK,” said Ramesh Patel, a local councillor, who called for an inquiry. He demanded to know why taxpayers’ money was “being wasted on trash like this”.

However, James Tyson, the theatre’s programmer, defended the performance. He said that Miss Takahashi was an internationally renowned artist and that her work constantly questioned the way products were marketed and the role of mass media in society. “This wasn’t just about a woman drinking a lot of beer” he added, “This was a powerful piece of art.” Mr Tyson’s explanation failed to convince everyone. David Davies, a member of the Welsh Assembly and another philistine, said: “If anyone is daft enough to want to see a young woman getting plastered and tottering around in high heels, they can do it in just about every city centre most nights of the week. The show is probably the biggest waste of money in the world. The worrying thing is people are deciding to hand out taxpayers’ money like this when they are sober.”

Whether or not Miss Takahashi’s show deserves the title of biggest waste of money may be a matter for debate. The Cardiff show took place more or less at the same time as The Tate gallery paid £20,000 for a another piece of performance art, Time, by David Lamelas, which involves asking people to stand in a line and state the time to the person next to them. A commentator explained that the advantage of the show was that the gallery would be able to put it on at any time it wanted.

Children in the spotlight

The issue of underage drinking again received intensive media coverage as it came to light that a 10 year old child, believed to be a girl, had been referred to the Cumbria Alcohol and Drug Service having acquired a taste for alcopops.

It also emerged that in 2004, 1,600 children, some of them very young, called Childline for help with alcohol problems, in many cases caused by their own drinking.

Paul Brown, director of the Cumbria Drug and Alcohol Advisory Service, was in charge of the case of the 10 year old. He has previously spoken of girls as young as seven reporting drinking alcopops. He said: “Giving a child one of these drinks is like handing them a double shot of gin. Alcohol used to be an acquired taste. It took you a while to get used to the bitter taste. Alcopops have done away with that.”

Commenting on the case, Dr Guy Radcliffe of the Medical Council on Alcoholism, said: “The beverage industry cannot seriously expect us to believe that these drinks were introduced for any other reason than to attract younger people.”

Dr David Regis, of the Schools Health Education Unit, agreed but said: “It’s extraordinary a 10-year-old should have enough access to alcopops to develop a problem.”

However, the cases reported by Childline suggest that even young children having access to alcopops is not that unusual. ChildLine’s Brendan Paddy, speaking to the Daily Mirror, said most young drinkers who called were between 12 and 15 but some were under 11. One reported case is that of a 13 year old girl who phoned the helpline and said she thought she was an alcoholic. The girl said she had been drinking for two years and went on: “I have a drink in the morning before I go to school. I have more at lunchtime then drink after school until my grandparents get in.” She added “I get moody when I haven’t had a drink”.

The Mirror also reported a hotel worker as saying that children as young as six had been caught drinking alcopops at weddings. But he added: “When the drinks were confiscated we were confronted by angry parents demanding a refund.” Parents are the main source of alcohol for children of these ages, perhaps not always intentionally. Recently, the University of Wales Institute in Cardiff produced a report ‘From Lollipops To Alcopops’, describing how alcopops were often bought for and served to children at family parties and BBQs by their parents.

The researchers spoke to parents and to children aged from nine to 13-years-old at five schools in South Wales. Focus groups showed that although parents see illegal drugs as dangerous, many accept alcohol as ‘safe’.

Dr Bev John, who led the research said, “The thinking behind it was we wanted to develop ways of giving youngsters ways to develop sensible attitudes to alcohol. We were quite surprised when we interviewed a lot of children and parents and found there is a lack of awareness of what alcopops really are. We are concerned at the way parents normalise alcohol because they are so frightened of illegal drugs.”

A recent survey for the alcohol industry’s Portman Group found that almost one third of adults reported being asked to buy alcohol for someone aged under 18, and over a third of those who had been asked had actually done so. A substantial proportion of adults said that they did not know that the proxy buying of alcohol for minors was illegal.

Illegal sales to the underage

Under 18s appear to have little difficulty buying alcohol for themselves. The Government inspired ‘sting’ campaign that took place over the summer of 2005 found that over half (52 per cent) of the on-licensed premises tested sold alcohol to the underage. This compared to just over one third (36 per cent) of the off licences. However, just under one half (48 per cent) of the supermarkets sold alcohol to the underage, and figures obtained by The Sunday Times suggest that Tescos is the biggest culprit. Over half (52 per cent) of Tesco stores tested sold alcohol to the underage, compared with 42 per cent of ASDA stores and 30 per cent of Sainsburys.

Government crackdown

Tackling underage drinking was a major theme of the package of measures announced again before the coming into force of the new Licensing Act at the end of November.

Home Secretary Charles Clarke launched a nationwide campaign by police and trading standards officers to target those who sell alcohol to under 18s, bars and clubs that promote irresponsible behaviour and drunken individuals who cause violent disorder. All of the measures included in the campaign had already been announced previously, some being provisions of the new Licensing Act. The Government pledged £2.5 million to boost a range of specialist operation including: issuing of fixed penalty notices for alcohol related disorder; test purchasing activity to target underage sales; early intervention using CCTV to diffuse potential disorder; closure of premises using existing and tough new power in the Licensing Act 2003; and multi-agency enforcement action against problem premises/retailers.

Helping to launch the crackdown, Ron Gainsford, Trading Standards Institute Chief Executive, said, “We in Trading Standards are constantly staggered by the volume of illegal alcohol sales to under 18s. There can be no excuse for retailers, no matter what their size, selling to youngsters. Under age sales easily lead into binge drinking, anti-social behaviour and crime and disorder. The health and welfare of young people and communities are too important to ignore – that is why it is imperative we stop alcohol passing across the counter to the hands of vulnerable minors.”

Measures against underage drinking contained in the new Licensing Act include increased penalties for selling alcohol to children (up to £5000) and making it possible for courts to suspend or forfeit personal licences at first offence and not only on second conviction as under the old licensing regime.

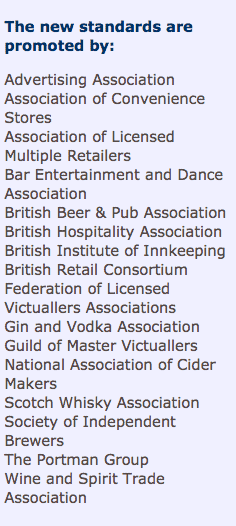

New drinks industry standard on social responsibilities

Home Office Minister Paul Goggins joined the UK drinks industry to launch a comprehensive set of standards to improve good practice in the sale of alcoholic drinks.

Home Office Minister Paul Goggins joined the UK drinks industry to launch a comprehensive set of standards to improve good practice in the sale of alcoholic drinks.

Social Responsibility Standards for the Production and Sale of Alcoholic Drinks in the UK has been developed by the drinks industry in partnership with the Government, and it fulfils one of the main commitments of the National Alcohol Harm Reduction Strategy. The code addresses the responsible advertising, marketing and retailing of drinks right through the supply chain in both the ‘on-trade’ and ‘off-trade’ sectors.

Speaking at the launch of the Standards in Manchester Paul Goggins, said: “The industry has a clear responsibility to ensure that bars, off-licenses, supermarkets and clubs are run in a way that promotes good practice. We welcome the responsible approach being taken with the publication of the Principles and Standards document that sets out how this can be achieved.

“However, publishing the document is only the beginning. We are very keen that the document is used across the trade, including the supermarkets, and that individual trade associations put into place policies and initiatives for promoting and implementing it.

“These standards are something the industry has been keen to produce, and now we expect to see a real impact on the ground. But the industry must be clear that those who spurn such guidance and continue to contribute to alcohol related disorder will be targeted and face the full force of the law.”

The wide-ranging new standards provide practical guidance to the industry and others on how to promote sensible drinking, clamp down on irresponsible promotions, avoid contributing to problems of drunkenness, and to take action to clamp down on underage sales. The industry is also ensuring that alcohol is not promoted in a way that might appeal to under 18s, to make the alcoholic nature of drinks clear, and to ensure that staff in the industry are aware of these standards and have the right training to ensure they are met.

Rob Hayward, Chief Executive of the British Beer and Pub Association, which coordinated the development of the new code, said: “We are determined to promote the highest possible standards in our industry, and this document will help us to drive the whole process forward. We recognise that we have a role to play in addressing alcohol misuse, and this shows our commitment to working with the Government to tackle these problems. We now have a code which provides a framework on social responsibility for us all to work together, with the same objectives, and in partnership with the Government.”

Alcohol Social Responsibility Principles

The code commits member companies of the trade associations supporting the Standards who are involved in the production, distribution, marketing and retailing of alcoholic drinks to following agreed principles within their own areas of responsibility in all their commercial activities:

- To promote responsible drinking and the ‘Sensible Drinking Message’.

- To avoid any actions that encourage or condone illegal, irresponsible or immoderate drinking such as drunkenness, drink driving or drinking in inappropriate circumstances.

- To take all reasonable precautions to ensure people under the legal purchase age cannot buy or obtain alcoholic drinks.

- To avoid any forms of marketing or promotion which have particular appeal to young people under the age of 18 in both content and context.

- To avoid any association with violent, aggressive, dangerous, illegal or anti-social behaviour.

- To make the alcoholic nature of their products clear and avoid confusion with non-alcoholic drinks.

- To avoid any suggestion that drinking alcohol can enhance social, sexual, physical, mental, financial or sporting performance, or conversely that a decision not to drink may have the reverse effect.

- To ensure their staff and those of companies acting on their behalf are fully aware of these Standards and are trained in their application in their own areas of responsibility.

- To ensure that all company policies work to support these standards.

Temperance old and new

At a time when alcohol consumption and the problems associated with drinking have risen up the political agenda and come frequently to dominate the news headlines, historian Virginia Berridge has examined the history of temperance and concludes that the history of temperance offers many options for the present and the future.

In a report commissioned by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Professor Berridge suggests that despite the image of temperance as a rigid and moralistic movement aiming at total abstinence and with little relevance to the present, in reality temperance had a more varied agenda, including the idea of progressive restriction and modification of drinking.

Temperance history, Professor Berridge says, shows that the issue of cultural change is central. Temperance helped change drinking culture but also built on more general social change. Such cultural change can be achieved in society through avenues like the media, which have changed their attitude to alcohol.

Professor Berridge also identifies other strong themes of temperance history having direct relevance for today.

- The local dimension was important for temperance, and current licensing reform offers local government and local action opportunities which temperance reformers fought for in the 1880s.

- Women’s changed role in society and greater independence has been under- or misused in the current debate on alcohol by comparison with women’s past role in relation to alcohol misuse.

- The role of religion in achieving cultural change in a multicultural society is also currently underused by comparison with the position religion held in relation to drink in the past.

- Scientific messages are unclear and alliances with criminal justice interests could be more firmly established. An ‘advocacy coalition’ could have greater impact.

- Better public messages are needed, as in the nineteenth century. These could involve a range of drinking options, including abstinence.

- Political division on the drink issue may develop through licensing as it did in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. There will be, and are, opportunities for external coalitions to influence

developments.

- Temperance interests in the past worked with sections of the drinks trade to achieve moderate reform, and new alliances might be possible in the present, given the changing role of the industry.

- The history of allied policy areas like smoking, where policy has moved through different stages and cultural change has been achieved, offers a model for possible change for alcohol.

Temperance Its history and impact on current and future alcohol policy Virginia Berridge

Book review

Alcohol and crime – Gavin Dingwall

Reviewed by Jonathan Goodliffe

The law and lawyers are usually reluctant to focus on alcohol problems as a legal subject in its own right. The potential of the law (and not just the criminal law) as an means of helping to solve those problems tends to be ignored or dismissed. So I welcome the publication of this book.

The author, Gavin Dingwall, is a lecturer in law at the University of Wales, Aberystwith. He has worked and published research in the field of alcohol and crime over a considerable period. This includes a contribution to ‘Alcohol, Society and the Law’ edited by O’Donnell and Kilcommins (2003).

‘Alcohol and Crime’ is aimed at introducing “readers to the debate about the relationship between alcohol and crime and the way in which the criminal justice system responds to those who offend after consuming alcohol”. In a sense it is partly a sociological study and partly a legal paper. There are well researched chapters on ‘alcohol and society’ and ‘alcohol use and crime’. I found the historical and international material particularly interesting.

The chapter ‘explaining the frequent co-existence’ is an admirable introduction to the complex relationship (often best not explained in terms of simple causation) between the commission of a crime and the fact that the offender had been drinking. The next chapter discusses prevention and policing initiatives.

The author moves to legal analysis in the chapter ‘intoxication and criminal responsibility’. There has been much criticism of the case law which has developed in this context. The Law Commission of England and Wales initially suggested creating a separate offence for those cases (e.g. murder) where intoxication may sometimes prevent the defendant from having the criminal intent to sustain a conviction. Following its consultation this proposal was dropped, but Dingwall is attracted by the idea, arguing that it would “reflect the degree of culpability of the defendant more honestly, whilst at the same time ensuring that the law does not fall into disrepute”.

In ‘sentencing issues’ Dingwall is strongly critical of current legislative initiatives which he considers have “unravelled the coherence” of the Criminal Justice Act 1991. One of his more loaded comments is “Immediately after taking office, Tony Blair’s government fulfilled … its promise by introducing a number of reactionary criminal justice reforms.” He also seems to share many of the Institute of Alcohol Studies’ misgivings about the Licensing Act 2003.

The last chapter is a conclusion which ends with a plea for the use of measures which are “justified and proportionate”.

This is a brave effort to tackle a new and difficult subject. There are many interesting insights and much that is useful for reference purposes. On the other hand the overall focus is perhaps a little narrow.

In my view, in order to help readers (many of whom will be lawyers or law students) to understand how alcohol feeds into criminal behaviour, introductory material is needed not only on ‘alcohol and society’, ‘alcohol use and crime’ and ‘explaining the frequent coexistence’, but also on how alcohol problems are solved. There also, surely, needs to be some discussion of different theoretical approaches to alcohol problems, if for no other reason than to prepare the young lawyer for the many fundamental disagreements which exist between experts in this field. This discussion could include some mention of the International Classification of Diseases distinction between alcohol dependence and misuse, recent work on the relationship between dependence and problems, the disease concept and the controversy over abstinence and controlled drinking.

Despite Dingwall’s criticisms of the posturing of politicians he follows them to some extent in focusing on the most obvious manifestation of ‘alcohol related crime’ (an expression which he uses with some reluctance and no doubt for want of anything better) with very little coverage of drunken driving and other offences which may be related to alcohol dependence, such as theft, fraud and other ‘middle class’ crime.

It seems to me that Dingwall’s concept of ‘alcohol related crime’ is in any event too narrow. It is confined to cases where the offender commits a crime when he has alcohol in his system. My own experience, among other things, in helping lawyers with drinking problems (www.articles.jgoodliffe.co.uk), suggests that people’s behaviour often fails to match up with legal norms (both criminal and civil) because of the problems which arise from past as well as (or rather than) present drinking. These problems include, for instance, depression, cognitive impairment, and denial. Denial includes the enhanced ability to persuade oneself that one is justified in doing whatever one wants to do.

In studying alcohol related crime, one can use the commission of the crime as a starting point and work back to analyse its causes. An alternative or complementary approach is to use the people who have the problems arising from, or related to, alcohol as the starting point. The criminal behaviour of those people will usually be only one of their problems, but the solution may be a general one. Dingwall might not, perhaps, disagree with this proposition, but there is, in my view, a disproportionate focus in his book on working back from the crime.

A socio-legal approach to alcohol and crime (or indeed any area of the law) should also, in my view, focus not only on sentencing but on what happens before offenders get to that stage. In particular how much help do they and should they get from alcohol counsellors, AA volunteers, probation officers, lawyers and judges? Should lawyer training cover this subject as it does in some US states? Should a lawyer representing an alcoholic client not understand as much about alcohol problems as a personal injuries lawyer does about the medical problems of his client? If he wants to acquire that understanding there is not much in the way of reading material currently available to him. Mention of alcohol and drugs is often not to be found even in the indices of leading legal textbooks.

Dingwall’s work, despite its shortcomings, is a worthy starting point. The profession also urgently requires introductory material on subjects such as ‘alcohol and family law’, ‘alcohol and employment law’, ‘alcohol and housing law’, ‘alcohol and medical law’ and, of course, in more general terms, on ‘alcohol and the law’ itself.

Jonathan Goodliffe is a solicitor who writes from time to time on alcohol problems and the law.

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

Gambling industry harms and parallels with the alcohol world

Will Prochaska –

Coalition to End Gambling Ads