In this month’s alert

Government alcohol and drugs policy in disarray

The Government’s approach to tackling the problems of drugs, legal and illegal, was brought into severe question when the Home Secretary sacked its Chief Scientific Advisor on Drug Policy, Professor David Nutt, from his position as Chairman of the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD). The sacking followed publication of a briefing on drug policy written by Professor Nutt for the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies at Kings College, London.

In the briefing, which was written in his capacity as an academic rather than as Chairman of ACMD, he criticises the existing drug classification system for artificially separating legal and illegal drugs, and argues that cannabis and ecstasy are less dangerous than alcohol and tobacco. Professor Nutt criticises, in particular, the former Home Secretary, Jacqui Smith for ‘distorting and devaluing’ scientific research when she re-classified cannabis from Class B to Class A. Later, he also criticised Gordon Brown for being the first Prime Minister to go against the advice of his scientific advisors on drug policy.

Alan Johnson, the present Home Secretary, promptly demanded Professor Nutt’s resignation, stating that he had lost confidence in him as an impartial adviser to the Government. He said that Professor Nutt had been sacked not for his views but because he could not be an advisor to the government while simultaneously campaigning against government policy.

The sacking resulted in a major public row in which the Government was roundly condemned for attempting to gag scientists and accused of preferring to pander to popular prejudice than base drug policy on scientific evidence. Other members of the ACMD also resigned in protest, and there were widespread demands in the media and from the scientific community that new rules should be brought in to safeguard the independence of scientists who agree to participate in governmental scientific advisory committees.

While most of the coverage and comment regarding the row appeared to be framed in terms of ‘politicians versus scientists’, and to take Professor Nutt’s side in the dispute, there was a minority view which was less sympathetic. Some commentators took the view that it was perfectly reasonable for the Home Secretary to say that scientists advise but it is the government which decides policy, and agreed with Mr Johnson that Professor Nutt and the ACMD had crossed the line into territory which properly belonged to Government. Others accused the ACMD of diminishing its own scientific credibility by itself ignoring or downplaying the evidence on the harmfulness of cannabis and Ecstasy.

In a letter to The Guardian, Professor Robin Murray took Professor Nutt and the ACMD to task for having ‘an unfortunate history’ in relation to cannabis. Professor Murray wrote:

“In 2002, it boobed by advising David Blunkett, then Home Secretary, that there were no serious mental health consequences of cannabis use; the council had done a sloppy job of reviewing the evidence. Since that time, they have been trying to regain credibility, and now accept that heavy use of cannabis is a risk factor for psychotic illnesses including schizophrenia. However, Professor Nutt’s comments demonstrate how difficult it has been for some members of the committee to accept their error.”

Another critic was Professor Neil McKeganey, Director of the Centre for Drug Misuse Research at the University of Glasgow. Writing in the Scottish newspaper, The Herald, Professor McKeganey said that abolishing the distinction between legal and illegal drugs would open the possibility of much wider drug use and undermine efforts at drug prevention. He criticised, in particular, a claim previously made by Professor Nutt in which he had stated that Ecstasy was no more dangerous than horseriding. This claim, Professor McKeganey said, served only ‘to trivialise, normalise and ultimately encourage’ drug use, and represented ‘a very dangerous position for a government adviser on illegal drugs to take.’

Alcohol most dangerous drug

In a later interview to The Times, Professor Nutt amplified his views on the dangers of alcohol. It was alcohol, he said, that was the ‘gateway drug’ and it remained the greatest threat to society. The Government’s failure to address the problem epitomised its disregard for scientific evidence. Professor Nutt said that the comparison he made between the harm caused by alcohol and Ecstasy, which led to his dismissal as Head of the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, ‘was incontrovertible’.

“When I say alcohol is more dangerous than Ecstasy, cannabis and LSD, I mean it, and the council means it,” Professor Nutt said. “The Government has to wake up to this time bomb and the health risks of alcohol. Across the political spectrum everyone knows that alcohol is the biggest killer.” He added: “If alcohol was discovered tomorrow it would definitely be illegal. It’s a dangerous drug — there’s no doubt about that. There is an issue about understanding that it’s alcohol that will kill people’s kids, not Ecstasy.”

Professor Nutt advocated the tripling of alcohol prices, with taxation the most obvious way of achieving this.

The Centre for Crime and Justice Studies briefing

Professor Nutt’s briefing on drug policy makes clear that, in his view, alcohol poses the biggest drugs harm challenge. In ‘Estimating drug harms: a risky business’, Professor Nutt argues that the relative harms of legal drugs such as alcohol and tobacco are greater than those of a number of illegal drugs, including cannabis, LSD and ecstasy. Professor Nutt proposes a ‘drug harm ranking’, which compares the harms caused by legal as well as illegal drugs. Alcohol ranks as the fifth most harmful drug after heroin, cocaine, barbiturates and methadone. Tobacco is ranked ninth. Cannabis, LSD and ecstasy, while harmful, are ranked lower at 11, 14 and 18 respectively. Professor Nutt argues that simply focusing on the harms caused by illegal drugs, without assessing them against those of drugs such as alcohol and tobacco, results in an ‘isolated and arbitrary’ debate about relative drug harms.

Professor Nutt argues strongly in favour of an evidence-based approach to drugs classification policy and criticises the ‘precautionary principle’, used by the former Home Secretary Jackie Smith to justify her decision to reclassify cannabis from a class C to a class B drug. By erring on the side of caution, Professor Nutt argues, politicians ‘distort’ and ‘devalue’ research evidence. “This leads us to a position where people really don’t know what the evidence is”, he writes.

On cannabis, Professor Nutt makes clear that it is ‘a harmful drug’ and argues for a ‘concerted public health response… to drastically reduce its use’. However, he points out that cannabis usage fell when it was reclassified from class B to class C. And he points out that there is ‘a relatively small risk’ of psychotic illness following cannabis use. To prevent one episode of schizophrenia, he argues, it would be necessary ‘to stop 5,000 men aged 20 to 25 from ever using’ cannabis. On recent debates about the classification of ecstasy, in which the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) recommended it be classified as a class B drug, Professor Nutt writes that the ACMD ‘won the intellectual argument, but we obviously didn’t win the decision in terms of classification’.

Professor Nutt also criticises the quality of some research evidence on drug harms. There are, he writes, “some horrific examples where some of the so-called ‘top’ scientific journals have published poor quality research about the harms of drugs such as cannabis and ecstasy, sometimes having to retract the articles”.

Among Professor Nutt’s recommendations are:

Stopping the ‘artificial separation of alcohol and tobacco as non-drugs’. It will only be possible to assess the real harms of illicit drugs when set alongside the harms of other drugs ‘that people know and use’, he writes.

Improving the public’s general understanding of relative harms. He had previously compared the risks of taking ecstasy over the risks of horse-riding, he writes, because media reporting ‘gives the impression that ecstasy is a much more dangerous drug than it is’.

The provision of ‘more accurate and credible’ information on drugs and the harms they cause. Drug classification based on the best research evidence would ‘be a powerful educational tool’. Basing classification on the desire ‘to give messages other than those relating to relative harms… does great damage to the educational message’, he argues.

Professor Nutt said:

“No one is suggesting that drugs are not harmful. The critical question is one of scale and degree. We need a full and open discussion of the evidence and a mature debate about what the drug laws are for – and whether they are doing their job.”

Supporting delivery – England’s Fourth National Alcohol Conference, Aintree, 24-25 November 2009

England’s 4th National Alcohol Conference, `Safe Sensible Social: Supporting Delivery’, took place at Aintree, Liverpool in November 2009. Hosted by the Home Office, the Department of Health and the Department for Children, Schools and Families, it was designed to give further momentum to the alcohol harm reduction strategy, particularly in relation to local developments. Aneurin Owen, who represented IAS at the conference, sums up what he thought it accomplished.

Five years into the Alcohol Harm Reduction Strategy, it is still early days – some gains have been made – but there is a long way to go. The Conference was a showcase for local and national initiatives but fell short of addressing the key policy areas that would significantly reduce alcohol-related harm in the UK.

References to population-level measures were conspicuous by their absence in several keynote addresses and it was left to ‘critical friends’ – Don Shenker, Mark Bellis and others – to challenge progress made on protecting young people, marketing, price, availability and access.

Call for minimum pricing

Dr Arif Rajpura, Director of Public Health, NHS Blackpool, made a strong case for government action on minimum pricing and for the alcohol field in all its diversity to advocate actively for this to be introduced. He was not a lone voice as was clear from the participants’ reaction. It was confirmed by ministers and senior officials from the Department of Health and the Home Office that minimum pricing is a live issue and further research has been commissioned.

Responding to a challenge as to why further research is required, following publication of the Sheffield reports:

It was said that the Government requires greater understanding of the economics of the drinks industry – how pricing policies work through the commercial chain which is currently shrouded in lack of transparency

The Home Office requires further detail on the impact of minimum pricing on the criminal justice service – there is good analysis on the impact on health.

The Government wishes to consolidate public support for any measures taken and that more time is required to consult, convince and carry public opinion on this issue

Alcohol or Drunkenness Harm Reduction Strategy?

Several presentations and workshops focussed on the success of partnership approaches and problem solving approaches to managing night-time economy, antisocial behaviour and youth crime. This is a key theme in the strategy and the delivery of local and regional actions has readymade support. Increasingly, however, the impression given is that the strategy is addressing the management of intoxication and that there should be more incisive action from government to introduce effective population-based approaches to create the right environment for local actions to achieve sustainable outcomes on reducing all alcohol-related harm. As Mark Bellis commented, “England has become an international expert on creating safe environments for intoxication”.

Government action

The government will roll out an information and awareness campaign in the new year based on the CMO’s guidance to parents and children. This programme will be preceded by a brief PR exercise before Christmas. David Chater from DCSF confirmed that this campaign has been developed in partnership with parents and will be based on the weight of medical opinion that delaying the onset of drinking is best for children and the need to build resilience and aspiration.

Changing cultural attitudes in this way will be supported by new measures introduced in the Policing and Crime Act – persistent possession, dispersal powers to include those over 10 years old (previously 16 years) and the mandatory code of practice.

From the examples presented at the Conference, significant progress has been achieved within and across government departments and at regional and local levels. However, the lasting impression left by the conference was a call to government: “Support our efforts and delivery by acting on price”.

24 hour licensing under threat

Both major political parties have now signalled that the new licensing regime in England and Wales will be tightened up, and with the Scottish National Party continuing with its plan to introduce minimum prices for a unit of alcohol it looks as if the price and availability of alcohol will remain high up the political agenda.

Speaking at the Labour Party conference in Brighton, Prime Minister Gordon Brown appeared to repudiate a key part of the licensing reforms introduced by his predecessor, Tony Blair. A week later at the Conservative Party conference, Shadow Home Secretary, Chris Grayling, also promised tough action from a future Conservative government.

Labour to restrict opening hours

In his last party conference speech before the general election, in the part of the speech concerned with crime and anti-social behaviour, Mr Brown said:

“We will never allow teenage tearaways or anybody else to turn our town centres into no go areas at night times. No one has yet cracked the whole problem of a youth drinking culture. We thought that extended hours would make our city centres easier to police and in many areas it has. But it’s not working in some places and so we will give local authorities the power to ban 24 hour drinking the interests of local people.”

Later, the Department for Culture, Media and Sport appeared to confirm that changes to the Licensing Act 2003 are being planned. Speaking to The Publican newspaper, a spokesman confirmed that the government is seeking to alter the Licensing Act to give councils the powers to restrict the opening hours of every licensed venue, including off-licences and supermarkets, in a problem area.

Council officers will also be given the right to review the trading hours of a premises, regardless of whether the police or residents have complained.

The changes will require primary legislation and will see a full consultation before the proposals go through Parliament.

The spokesman said:

“We will give councils the powers to impose a complete blanket ban on 24-hour licenses in a particular area – such as a street, city centre, or the whole of the local authority area.

“Councils will still make the majority of licensing decisions on opening hours on a case-by-case basis, but we accept that there are times where disorder cannot be attributed to individual premises.

“We will also introduce a new power to make it easier and faster for councils to restrict or remove individual pub and club licenses where there are problems.

“We accept the arguments put to us by local government that councillors should be able to call for reviews without having to wait for a resident or the police to make a complaint.

“This change will make it easier for licensing authorities to bring problem premises to review.”

According to the DCMS just 10 per cent of 24-hour licenses – 640 in total – are pubs, bars and nightclubs. In his conference speech, Mr Brown also made another pledge:

“And let me say this bluntly; when someone is found guilty of a serious crime caused by drinking, the drink banning order which is available to the courts should be imposed. And where there is persistent trouble from binge drinking, we will give local people the right to make pubs and clubs pay for cleaning up their neighbourhood and making it safe.”

The idea of making licensees pay a special levy to cover the cost of policing and cleaning up the night-time economy is not, of course, new. Indeed, Mr Brown appeared to be promising to introduce a measure which already exists, it having formed part of the legislation on Alcohol Disorder Zones which came into force on 5 June 2008. These are designed to help local authorities and the police tackle high levels of alcohol related nuisance, crime and disorder that cannot be directly attributable to individual licensed premises. However, as, so far as is known, not a single local authority has made use of the legislation to designate an alcohol disorder zone, no licensees have ever been made to pay the levy.

The fact that one of Mr Brown’s proposed measures to tackle binge drinking already exists in theory, albeit not in practice, and that, if the opinion polls are accurate, Mr Brown will not be around after the next general election to rescind 24 hour licensing, should not, however, provide much comfort for the licensed trade. For spokesmen for the main opposition party have also threatened to reform the Licensing Act 2003, and, in particular, the extended hours granted by the Act.

Conservatives “will tackle alcohol-fuelled antisocial behaviour”

Speaking at the Conservative Party conference, Shadow Home Secretary, Chris Grayling, promised a future Conservative Government would introduce a much tougher licensing regime, with local councils and the police being given new powers to restrict the large number of late licenses awarded to shops, takeaways and other venues.

Other promised measures include:

Significant tax increases, including on alcopops, strong beer and strong cider, “that contribute to violence and disorder on our streets.” As a result, a 4-pack of super-strength beer will be £1.30 more expensive, a 2-litre bottle of super-strength cider will be 84p more expensive and a large bottle of alcopops will be up to £1.50 more expensive.

Supermarkets and other retailers will be banned from selling alcohol below cost price. This, Mr Grayling said, would help tackle the ‘pre-loading’ trend – young people and binge drinkers consuming cheap alcohol at home before going to town centres.

Police – 24 –hour drinking Act ‘should be reversed’

The Licensing Act 2003, which introduced 24 hour drinking, has failed and should be reversed, according to Garry Shewan, Assistant Chief Constable of Greater Manchester Police.

Addressing a police conference devoted to the theme of alcohol-related crime and disorder, Mr Shewan warned that the new Licensing Act ‘leaves police dangerously stretched.’ He said that the Government’s claim that the extension of drinking hours would stop the 11pm or 2am rush had not been borne out by events. He continued:

“The reality is it’s not stopped the rush and sometimes it has pushed the rush back. What used to be a late-night problem is sometimes in major cities extended to 16-18 hours and that clearly is a real risk. Bars and clubs are staying open much later and that puts a real strain on police resources. It would be far safer if the period of time people drink irresponsibly was reduced.”

Doctors call time on alcohol promotion

In a bid to tackle the soaring cost of alcohol-related harm, particularly in young people, the BMA has called for a total ban on alcohol advertising, including sports events and music festival sponsorship. In addition, the BMA also called for an end to all promotional deals like happy hours, two for-one purchases and ladies’ free entry nights. A new BMA report, ‘Under the Influence’, also renews the call for other tough measures such as a minimum price per unit on alcoholic drinks and for them to be taxed higher than the rate of inflation.

Launching the report, Dr Vivienne Nathanson, Head of BMA Science and Ethics, said: “Over the centuries alcohol has become established as the country’s favourite drug. The reality is that young people are drinking more because the whole population is drinking more and our society is awash with pro-alcohol messaging and marketing. In treating this we need to look beyond young people and at society as a whole.”

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), alcohol is the leading risk factor for premature death and disability in developed countries after tobacco and blood pressure problems. It is related to over 60 medical conditions, costs the NHS millions of pounds every year and is linked to crime and domestic abuse.

Alcohol consumption in the UK has increased rapidly in recent years; for example, household expenditure on all alcoholic drinks increased by 81 per cent between 1992 and 2006. And at the same time, says the author of the report, Professor Gerard Hastings, never before has alcohol been so heavily promoted.

Professor Hastings said:

“Given the alcohol industry spends £800 million a year in promoting alcohol in the UK, it is no surprise that children and young people see it everywhere – on TV, in magazines, on billboards, as part of music festivals or football sponsorship deals, on internet pop-ups and on social networking sites. Given adolescents often dislike the taste of alcohol, new products like alcopops and toffee vodka are developed and promoted as they have greater appeal to young people.”

“All these promotional activities serve to normalise alcohol as an essential part of everyday life. It is no surprise that young people are drawn to alcohol.”

The report claims that brand development and stakeholder marketing by the alcohol industry, including partnership working and industry-funded health education, have served the needs of the alcohol industry, not public health.

Dr Nathanson added:

“We have a perverse situation where the alcohol industry is advising our governments about alcohol reduction policies. As with tobacco, putting the fox in charge of the chicken coop – or at least putting him on a par with the farmer – is a dangerous idea. Politicians showed courage before by not bowing to the tobacco industry, they need to do the same now and make tough decisions that will not please alcohol companies.”

Key recommendations from the report include:

- A ban on all alcohol marketing and promotion

- Minimum price levels for the sale of alcoholic products

- Tax increases on alcohol set above the rate of inflation and linked to alcoholic content

- A reduction in licensing hours for on- and off-licensed premises.

The full title of the report is:

“Under the Influence – the damaging effect of alcohol marketing on young people”.

Alcohol sponsors should have to prove they do no harm

Researchers from Australia and the UK have called for a new approach to the debate over whether alcohol industry sponsorship of sports increases drinking among sports participants. They want to shift the burden of proof to the alcohol industry.

The debate over sports sponsorship saw renewed activity in 2008 when the findings of a New Zealand study among sports participants showed that those who received alcohol industry sponsorship – especially in the form of free or discounted alcohol – drank more heavily than those not in receipt of such sponsorship. The study received extensive media coverage, but the Portman Group (a public relations body set up by the alcohol industry) and the European Sponsorship Association (whose members include leading alcohol producers) dismissed the results, citing no causal relationship between sponsorships and alcohol misuse.

In an editorial in the journal Addiction, researchers say that the alcohol industry should be required to prove that industry sponsorship of sports does not cause unhealthy alcohol use among adults or encourage children to drink. They argue that “it should not be left to the public to demonstrate that alcohol industry sponsorship is harmful but rather, it should be up to the proponents of the activity, i.e., the alcohol industry, to show that the practice is harmless.” Lead author Dr Kypros Kypri said that the position taken by the drinks industry is reminiscent of that taken by the tobacco companies, which until the 1990s doggedly denied that there was proof of a causal association between smoking and lung cancer. Until the industry has proved lack of harm, governments should prohibit alcohol industry sponsorship of sports.

Dr Kypri suggested that “The latest moves by the major sporting codes in Australia, to lobby against the regulation of alcohol sponsorship of sport, are indicative that these bodies remain in denial of alcohol-related problems in their sports. In addition, it is clear that these organisations have enormous vested interests in continuing to receive alcohol money and government should be careful to act in the public interest rather than cave in to the sports and Big Booze.” Co-author Dr Kerry O’Brien of the University of Manchester added that “Sport administrators are sending mixed messages to sportspeople and fans when on the one hand they embrace and peddle alcohol via sport, yet on the other punish individual sport stars and fans when they display loutish behaviour while under its influences.”

In place of industry sponsorship, the researchers suggest that governments use the proceeds from alcohol taxation to sponsor sports via an independent body. Such an approach is already in place in Australia and New Zealand, where tax revenues from tobacco sales are used to sponsor sports and other activities through publicly accountable agencies. The authors point out that this has the added advantage of providing a more equitable and accountable basis for allocating sponsorship of elite and community sport than leaving it up to the alcohol industry to decide who gets funded.

Kypri K., O’Brien K., Miller P. Time for precautionary action on alcohol industry funding of sporting bodies. Addiction 2009; 104: 1949-1950

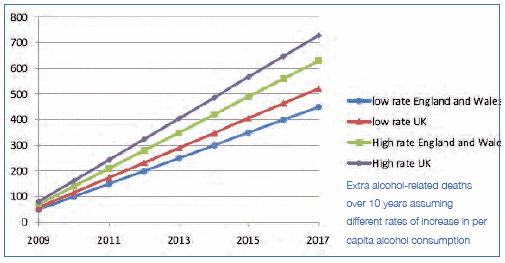

100,000 people could die as a result of their drinking over next ten years

Almost 100,000 people could die over the next ten years as a direct result of their drinking, according to Alcohol Concern, on the basis of a report they commissioned from the Alcohol & Health Research Unit at the University of the West of England, released to coincide with the start of Alcohol Awareness Week in England in October 2009. The report, ‘Future Proof’, suggests that in the UK 90,800 people could die avoidable deaths from alcohol-related causes by 2019 if the population continue to drink at the average rate of the past 15 years.

The report also highlights ONS statistics which show that deaths from alcohol are highest among older people, supporting Alcohol Concern’s view that the focus on encouraging ‘sensible drinking’ among young people should be widened to target the whole population.

Commenting on ‘Future Proof’, Professor Ian Gilmore, President of the Royal College of Physicians and Chair of the Alcohol Health Alliance UK said:

“Over the next decade alcohol misuse is set to kill more people than the population of a city the size of Bath. Much of this tragic loss of life, often in young and otherwise productive people, could be prevented if our policymakers followed the evidence for what works. Confronting the culture of low prices and saturation advertising, along with investment in accessible, effective treatments for harmful and dependent drinkers could make a big impact on what is becoming a public health emergency.

” Professor Martin Plant, lead author of the work said:

“The UK has been experiencing an epidemic of alcohol-related health and social problems that is remarkable by international standards. It is strongly recommended that reducing mortality should be the top priority for alcohol control policy. This could be done by introducing a minimum unit price of 50p which would cut alcohol-related hospital admissions, crimes and absence days from work.

Only 100,000?

Launching the report, Alcohol Concern made the astonishing claim that it broke new ground in calculating the relationship between alcohol consumption and mortality for the first time in the UK, a claim repeated in the published summary of the report itself. In reality, the relationship has been studied extensively over many years, with numerous researchers concluding that alcohol is the cause of rather more deaths than the 9,000 or so per annum suggested in ‘Future Proof’. An Oxford University research team estimated that in 2005 there were 31,000 deaths attributable to alcohol in the UK. The discrepancy derives from the different methodologies employed, with the Alcohol Concern report including only diseases directly caused by alcohol and alcohol poisoning, but excluding deaths caused indirectly by alcohol, such as those from drink-driving or cancers which have been caused in part by drinking.

Key Findings from ‘Future Proof’

The report states that alcohol consumption in the UK has increased rapidly in recent years so that the UK is now among the heaviest alcohol consuming countries in Europe. In England, over a third of men report drinking over 21 units in an average week and among women a fifth report an average weekly consumption of over 14 units. In Wales, nearly 40% of adults admit to consuming more than the recommended limits. In Scotland, 1 in 3 men and 1 in 4 women exceed recommended daily limits. Across Britain, 1.1 million adults are alcohol dependent. It is estimated that the annual cost of alcohol misuse to the NHS is £2.7 billion in 2006-07 prices. In 2008 the government estimated that the total cost of harm from alcohol was between £17.7 and £25.1 billion per year.

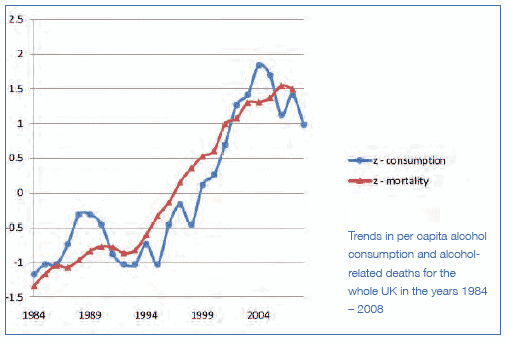

Link between consumption and harm

The research presents a clear correlation between increase in alcohol consumption per capita and the number of additional deaths that would occur as a consequence. Findings suggest that an increase of one litre in per capita consumption would be associated with approximately 928 extra alcohol-related deaths in the UK per year. Given the average increase in per capita consumption of 0.0875 litres over the past 15 years, an extra 810 deaths would occur across the UK over the next 10 years if the country continues to drink at the rate of the past 15 years. In Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, these levels of association between consumption and mortality were the strongest, the effect of consumption levels being evident immediately in mortality rates. In England, there was a one-year time lag between consumption changes and mortality.

Future Proof – Can We Afford the Cost of Drinking Too Much? – How to stem the tide of alcohol harms

The report says that because of the link between consumption and harm, the government’s strategy should be to lower overall alcohol consumption levels for the whole population, targeting a reduction in heavy drinking amongst all age groups. Price is the most effective, efficient and evidence-based lever to achieve this. Therefore, policies should include the introduction of a minimum price per unit of alcohol to stamp out loss-leading and the sale of high volumes of alcohol at very low prices, especially in off-licenses and supermarkets. Government should also consider a revision of alcohol duty, linking it to product strength in order to encourage both the production and consumption of lower alcohol beverages.

Other recommendations are that all alcohol products should show mandatory unit and health information, including the sensible drinking guidelines, and brief intervention and advice should routinely take place in all primary health and social care settings to help identify those that are drinking at unsafe levels. International evidence and practice shows there is a reduction in the health care needs and associated costs if front line services are able to identify at an early stage those who are drinking too much and help them reduce their consumption, directly or through referral to specialist services.

Mandatory code still on the agenda

The power to impose statutory regulations on the selling of alcohol, designed to outlaw irresponsible drinks promotions, was, after all, included in the Policing and crime Act which received Royal Assent in November 2009.

There had been considerable doubt as to whether the controversial mandatory code on the retailing of alcohol, announced to a fanfare of publicity earlier in the year, would ever actually be introduced, particularly after Lord Mandelson, the Business Secretary, and normally reckoned to be the Deputy Prime Minister in all but name, pleased the alcohol industry and disappointed many in the public health sector by calling for a delay in introducing the code until after the next general election.

However, the Home Office, which still favoured the early introduction of the Mandatory Code, appears to have won the day. The Policing and Crime Act introduces an ‘enabling power’ whereby the Home Secretary can draw up a code of practice for the alcohol industry which will permit the imposition of some mandatory licensing conditions and allow licensing authorities to ‘block apply’ conditions to a number of premises at a time. At the time of writing, however, the content of the code appears not to have been decided, and it is not entirely clear what the next steps will be or what timescale will apply.

Prime Ministerial initiative

Prior to the passage of the Policing and Crime Act, a draft code was put out to extensive consultation with stakeholders including the trade, police, local authorities and alcohol NGOs. The code was originally announced by Prime Minister Gordon Brown as the latest Government initiative to combat binge drinking. It was presented as a means of outlawing promotions aimed at encouraging customers to drink more than they would otherwise have done, such as drinking games, the provision of free drink for certain groups, and offers to ‘drink as much as you like’ for a fixed fee. These promotions, Mr Brown said, could turn some town centres into no-go areas.

Predictably, Mandelson’s attempt to delay was attacked by some in the alcohol harm prevention lobby. In a letter to the Times newspaper, Don Shenker of Alcohol Concern and Professor Ian Gilmour of the Royal College of Physicians accused the Government of favouring profit over health. The letter was also signed by Alison Rogers of the British Liver Trust and Mike Craik, Chief Constable of Northumbria Police. The letter said:

“When the mandatory code for alcohol sales was announced six months ago it was already a long overdue measure, designed to tackle patently irresponsible promotion of alcohol, such as the ‘drink all you can’ offers and giveaway prices in supermarkets.

“Delaying the measure until 2011 – effectively shelving it indefinitely – would be a costly error and appears to pander to big business concerns over profit at the expense of safer streets and public health.”

However, the disappointment at Lord Mandelson’s attempt to delay the Code was not shared by all non-business stakeholders.

Some local authorities had attacked the Code for being little more than another gimmick. The City of Westminster, normally regarded as one of the toughest licensing authorities in the country, questioned whether the new powers in the Code would have any effect as powers already existed in the Licensing Act to deal with problem alcohol retailers. Westminster also pointed out the lack of coherence in policy, with the Mandatory Code seeming to impose the very list of mandatory conditions on licensed premises that the Ministerial Guidance to the new Licensing Act disallowed. The London Borough of Lambeth criticised the Code for focusing on pubs when the real problem was very cheap alcohol being sold from off licenses, especially the supermarkets.

Oldham tackles supermarket alcohol sales

- The Mandatory Code may still not be a reality, and the legality of minimum pricing may be in dispute, but at least one local licensing authority has decided to take its own initiative on supermarket sales of alcohol. The Trading Standards and Civil Resilience department of Oldham Council has sent out a letter to all supermarkets in the borough setting out new proposals to review their drinks licenses and require them to adopt additional measures if alcohol is to be sold at less than fifty pence per unit of alcoholic strength.The letter explains the concerns of the Council regarding irresponsible drinks promotions. These, the Council says, encourage alcohol misuse and/ or antisocial behaviour. The cumulative effect of irresponsible drinks promotions is to cause greater drunkenness, which, in turn, causes a rise in crime and disorder. The letter also refers specifically to the problem of ‘pre-loading’, and to the attractiveness of irresponsible drinks promotions particularly to young people, and the problems that causes. For example, the effect of drinking excessive amounts of alcohol can be that people vomit or urinate in the streets, which is a public nuisance.

The letter explains the Council’s objectives in setting out new licensing conditions for supermarket sales of alcohol. These are:

- To reduce the available space for irresponsible drinks promotions in off licensed premises

- To increase the protective services available, both through promotion of responsible drinks messages and through adequate security supervision of drinks promotion

Accordingly, the letter sets out proposed conditions and invites licensees to comment. A key point is that the conditions are intended to apply only to premises which sell alcohol at less than 50p per unit of alcoholic strength. This is the same benchmark that the Council used for the on trade in Oldham Town Centre.

The proposals include:

- A license requirement that ‘designated alcohol sales zones’ be identified on the operating schedule of the premises. The specific location and size would vary according to the premises size, but would typically be two aisles in your premises

- That alcohol on sale below 50p per unit of alcoholic strength would not be permitted to be displayed outside of the designated zone

- That the designated zone be delineated by a barrier with entrance gates, the entrance gates clearly showing that no unaccompanied under-18s are permitted in the zone

- That each designated zone be patrolled during opening hours by an SIA registered security officer

- That the promotional material for alcohol on sale below 50p per unit of alcoholic strength be limited to a size less than 20cm by 10cm

- That one of a choice of five social responsibility messages be displayed within a circle of 1 metre diameter (field of vision) for each location where alcohol is on sale below 50p per unit of alcoholic strength

Price of alcohol influences drinking habits of heaviest drinkers

A new study suggests that minimum pricing of alcohol will reduce consumption amongst Scotland’s heaviest drinkers. The study which explored the drinking habits of patients referred to alcohol problems services in Edinburgh in 2008/09 found that:

- The lower the price a patient paid per unit of alcohol, the more units they consumed

- Most of the alcohol consumed was bought from off-licenced premises where the cheapest alcohol is sold. The average price paid per unit of alcohol was 34p which is much lower than the average paid per unit in Scotland as a whole

- Off-licensed purchases were made in roughly equal proportions from supermarkets and local/ independent shops

- 75% of patients reported never purchasing alcohol from on-licensed settings

- Vodka was reportedly the most popular drink, but it was noted that white cider provided a particularly cheap access to alcohol

- Patients in the study consumed on average 198 units of alcohol in a typical drinking week. The recommended weekly limit for men is 21 and 14 for women

Dr Jonathan Chick, coauthor of the study said:

“Information on drinking patterns usually comes from big population surveys. However, the heaviest drinkers in a population tend not to respond to surveys so this study provides important information on how price changes might affect those most affected by alcohol. Because the average unit price paid by these chronically ill patients was considerably lower than the rest of the Scottish population, it is likely that eliminating the cheapest alcohol sales by minimum pricing will result in reduced overall consumption by this group of drinkers with a fairly immediate reduction in serious alcohol-related illnesses in our community.”

A minimum price for a unit of alcohol of around 40 pence is mid-range of price levels suggested for discussion in the new Scottish strategy to tackle the substantial burden of harm due to alcohol use in Scotland. Alternative options to minimum pricing, such as a ban on the sale of alcohol below the cost of duty plus VAT payable on a product, have also been suggested.

Dr Bruce Ritson, Chair of Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems said:

“This emerging research makes an important contribution to the debate and adds to the evidence base on the likely health benefits of minimum pricing. Other alternatives that have been suggested are unlikely to deliver the same health benefits. If we had a ban on the sale of alcohol below the cost of duty and VAT instead of minimum pricing the price of white cider would remain unchanged and vodka could still be purchased for 26 pence per unit of alcohol. With six people dying an alcohol-related death every day in Scotland, we need to adopt the policy that is going to be most effective in reducing harm and saving lives.”

Dr Jonathan Chick is a Scientific Advisor to the IAS

Minimum alcohol price legal?

Further uncertainty overtook the Scottish Government’s plan to set a minimum price for alcohol when the European Court of Justice opposed a similar policy on tobacco. The Court’s advocate-general ruled against proposals by Ireland, France and Austria to set a minimum price on cigarettes, saying it would break competition laws by benefiting manufacturers. The drinks industry in Scotland immediately claimed that the ruling would apply to alcohol as well, and said that the plan for minimum alcohol prices should therefore be abandoned.

However, Health Secretary Nicola Sturgeon dismissed the industry’s claim, insisting that the court’s ruling on tobacco was “irrelevant”. The leader of SHAAP, (Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems) also defended the policy of minimum pricing.

Ms Sturgeon said:

“It is entirely inappropriate and irrelevant to translate an opinion on tobacco to the totally different issue of minimum pricing of alcoholic products per unit of alcohol for public health reasons. We are well aware of these cases, and the relevant Directive – 95/59/ EC – is specifically about the excise duty on manufactured tobacco and has nothing to do with alcohol products.

“In fact, the European Commission has already said that Community legislation does not prohibit minimum pricing for alcohol on public health grounds. Obviously, we rely on our own legal advice to progress this policy which is fair, proportionate and necessary to protect public health in Scotland.

“The issue here is ending a situation where three-litre bottles of chemical cider are sold for £3, or 700ml bottles of industrial vodka for less than £7. These are the products favoured by problem drinkers and are exactly the ones that will be targeted by minimum pricing – not quality products sold at responsible prices.

“Minimum pricing of alcohol has broad support base among medical experts, the police and the pub trade. Just last week, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) in England, the UK Government’s expert advisory body on medical treatment, strongly backed minimum pricing as a way of reducing consumption among harmful and hazardous drinkers.”

North West Directors of Public Health call for minimum price of alcohol

Legislation to introduce a minimum price for alcohol of 50p per unit, has been called for by a group of nineteen Directors of Public Health in the North West of England. Writing in a letter to The Times newspaper, the public health doctors urge the government to add a ban on selling alcohol below 50p per unit to the other measures it is proposing, to tackle the irresponsible sale of cut-price alcohol by the off-trade. The doctors continue:

“None of us comes to this policy solution easily. However, despite considerable investment in the NHS and public health messages, a new Licensing Act and efforts by the industry itself, HMRC figures show that the overall consumption of alcohol continues to rise, as measured by volume of alcohol sold. Hospital admissions due to alcohol harm have risen by 64% in the North West in the past five years. Apart from the implications for public health of this situation, we believe that the cost to the NHS in the North West of £400 million per year is simply unsustainable.

“Of course, personal responsibility must continue to be part of our collective focus in tackling alcohol consumption, but it is naive for any of us to think it can be the sole focus. Alcohol is sufficiently price elastic for the aggressive price-cutting we have seen in recent years to affect individual consumption. It follows, as Sheffield University has shown, that raising the price of the cheapest alcohol sold would affect overall consumption and would target effectively the consumption of those that drink above moderate levels.

“We know that the Government has argued that it does not wish to penalise moderate drinkers. Neither do we. A unit price of 50p means £1.50 for a pint in the pub or £4.50 for a bottle of wine in the supermarket. Is this really too much to pay to save 3,393 lives per year, to cut crimes by 45,800 and save the country £1 billion every year in alcohol-related costs?

“We urge the Government to act quickly and decisively. The political leadership that was shown on smoking in public places needs to be shown on alcohol too. As with smoking, the politicians that take a lead in combating alcohol harm may find that they command the public’s respect and support as a result.”

Department of Health under fire

The Department of Health’s approach to reducing alcohol-related harm has been heavily criticized by the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee (PAC) in its report ‘Reducing Alcohol Harm: health services in England for alcohol misuse’. The report examines how the Department responds to alcohol-related harm through Primary Care Trusts, responsible for determining local priorities and spending. It states:

“Many PCTs …. do not know what they spend on [alcohol] services and across England there is little correlation between need and expenditure. Where services Launching the report, the PAC’s Chairman, Edward Leigh MP, said:

“Too many people are drinking too much. In England, nearly a third of all men and a fifth of all women are regularly drinking more than the official guidelines say they should. In doing so, many are on course to damaging their health and general well-being.

“The burden on local health services is of course huge, with the rate of alcohol-related hospital admissions climbing sharply and A & E departments flooded on weekend nights with drink-associated injury cases.

“The responsibility for are commissioned there is frequently a lack of performance monitoring and examination of whether what is provided represents value for money.” addressing alcohol harm has been handed to the Primary Care Trusts. But many have neither drawn up strategies to tackle alcohol harm in their areas nor even have much idea what they are spending on the relevant local services. These services are often ill-coordinated, increasing the risk that dependent drinkers, after immediate medical care, will simply relapse into their former drinking habits. Each PCT should have to demonstrate what progress it has made towards reducing the number of alcohol-related hospital admissions in its area.

“None of this is helped by poor coordination between Whitehall departments on such relevant matters as licensing, taxation and glass sizes. The Department of Health should look across all departments, identify all the initiatives and policy areas bearing on alcohol misuse and determine the extent to which each is helping or hindering the Department’s objectives. Where the latter are being stymied, the Department should communicate its concerns to senior officials in the relevant departments.”

Mr Leigh was speaking as the Committee published its 47th Report of this Session which, on the basis of evidence from the Department of Health (the Department), examined the current performance of the National Health Service in addressing alcohol harm, the Department’s influence on local commissioners, and the Department’s work to encourage sensible drinking.

Background

In 2004, alcohol harm became subject to a national government strategy, which was updated by the Department and the Home Office in 2007. Since April 2008, the Department has also been responsible for delivering against a Public Service Agreement (PSA) indicator on the rate of increase of alcohol-related hospital admissions.

Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) are responsible for determining local health priorities and have control over the majority of NHS spending. PCTs are free to decide for themselves how much to spend on services to address alcohol harm. Many PCTs, however, do not know what they spend on such services and across England there is little correlation between need and expenditure. Where services are commissioned, there is frequently a lack of performance monitoring and examination of whether what is provided represents value for money.

In 2008, the Department introduced a number of new measures designed to help address alcohol harm: providing extra funding for GPs to screen new patients, increasing alcohol specific training for doctors, and creating 20 pilot sites designed to improve specialist treatment services. The Department has, however, yet to demonstrate its ability effectively to influence local commissioners, the drinks industry, and people’s drinking behaviour. The Department also needs to work more closely with the other government departments which are responsible for policies affecting alcohol consumption, such as taxation and licensing.

Achieving this will be necessary if the Department is to reduce levels of alcohol harm and succeed against the PSA indicator. The PAC report makes 10 key conclusions and recommendations:

Alcohol misuse places a large and growing burden on local health services; in particular, accident and emergency departments.

Some preventive services, such as ‘brief advice’… can be delivered effectively by…other officials outside the health service, but this requires effective partnership working at the local level. There is little evidence that this is happening.

General Practitioners (GPs) have an important role to play… but are not doing so consistently. A new scheme [the DES] to encourage such work is likely to have only limited effects.

Only around 1 in 18 people who are dependent on alcohol receive treatment and the availability of specialist services differs widely across England.

…there is frequently a lack of monitoring of whether what is provided by the public, private and voluntary sectors represents value for money.

[Treatment] services are often not joined up, increasing the risk that people will simply relapse into their former drinking habits.

The Department’s sensible drinking guidelines were changed from weekly to daily limits in 1995, but 11 years later almost two-fifths of people did not know the current recommended guidance.

By July 2008, only 3% of alcoholic products had fully complied with the drinks industry voluntary labelling scheme.

There is little evidence that Whitehall-wide action on other policies and regulations which affect alcohol consumption – such as licensing, taxation and glass sizes – is effectively coordinated.

Alcohol has become steadily cheaper in relation to income; meanwhile, consumption and health damage have increased.

Responding to the publication of the Public Accounts Committee’s report ‘Reducing Alcohol Harm: Health services in England for alcohol misuse’, Professor Ian Gilmore, President of the Royal College of Physicians and Chairman of the Alcohol Health Alliance said:

“It clearly demonstrates that the delivery of alcohol policy locally has been uncoordinated and muddled, and the effect on those particular interventions left unevaluated. The Government must now focus on better policy coordination and a clear mandatory framework rather than voluntary partnerships with industry. Above all it must prevent harm and drive down overall consumption through introducing a minimum unit price for alcohol.”

Department of Health to develop National Liver Strategy

- The Department of Health has announced that it is to implement a National Strategy for Liver Disease, of which alcohol is the largest single cause. A first step is the appointment of a new National Clinical Director to lead the development.Liver disease is the fifth most common cause of death in England and, the Department says, if action is not taken to combat the disease, it could overtake stroke and coronary heart disease as a cause of death within the next 10-20 years. The growth in liver disease is largely fuelled by lifestyle factors such as excessive drinking and obesity and could easily be prevented. The Department is to recruit a National Clinical Director in the next few months to develop and oversee the implementation of a strategy to combat Liver Disease effectively. Health Minister Ann Keen said:

“Liver disease is the only one of the top five causes of death which is continuing to affect more people every year at an increasingly young age. We know that by identifying people earlier, encouraging people to change their behaviour and making sure the right services are in the right place, we can improve the quality of care and stop the rise in this disease. By appointing a National Clinical Director to oversee the development of a strategy we will ensure that clinical evidence and outcomes for patients are at the heart of our work to improve the quality of services to tackle liver disease. We will continue to work closely with the NHS and patient groups to make a real difference for patients and for the healthcare staff working in this area.”

Liver disease facts:

- The average age of death from liver disease is 59, compared to 82 for heart disease and 84 for stroke

- Liver disease is largely preventable and can be treated if diagnosed sufficiently early

- Obesity is a rising cause of liver disease, with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) a growing concern amongst liver specialists

- While lifestyle factors such as drinking and obesity are the biggest causes, liver disease can also be caused by viral hepatitis, excessive iron and rare disorders

- Liver disease currently costs the NHS £460m a year

Scotland tops UK alchol league

Figures on alcohol consumption and harm show that Scotland not only remains top of the alcohol league in the UK, they also suggest Scotland has the eighth highest alcohol consumption level in the world. According to industry sales figures, Scotland drank nearly 50 million litres of pure alcohol in 2007 – equivalent to 11.8 litres per capita for every person aged over 16. This was considerably higher than England and Wales, which had an average consumption figure of 9.9 litres per capita.

For Scottish adults aged over 18, moreover, the figure was even higher at 12.2 litres of pure alcohol per person, while the figure for England and Wales was 10.3 litres.

Scotland’s pure alcohol per capita figure of 11.8 litres is equivalent to 570 pints of 4 per cent beer, nearly 500 pints of strong 5 per cent lager, 42 bottles of vodka or 125 bottles of wine – enough for every single adult to exceed the sensible drinking guidelines for men of 21 units every week of the year. And the difference between Scotland’s consumption and that of England and Wales, of 189 units per person, equates to 80-90 pints of beer or 21 bottles of wine more per head.

The figures are derived from market data analysed by the Nielsen Company for the Scottish Government, which also showed that two-thirds of alcohol in Scotland was bought in off-sales locations such as supermarkets.

Compared with the latest figures compiled by the World Health Organisation, this would place Scotland as having the eighth highest pure alcohol consumption level, behind only Luxembourg (15.6 litres per capita), Ireland (13.7 litres), Hungary (13.6 litres), Moldova (13.2 litres), Czech Republic (13.0 litres), Croatia (12.3 litres) and Germany (12.0 litres). England and Wales’ figure of 9.9 litres per capita would place it at fifteenth – equal with Lithuania.

Scotland’s figure is higher than nearly every other country in Western Europe, including Spain (11.7 litres), France (11.4 litres) and Italy (8.0 litres). It is more than double the consumption level in Scandinavian countries like Sweden (6.0 litres) and Norway (5.5 litres) where the relative price of alcohol is considerably higher and the sale of alcohol is more restricted.

Commenting on the figures, Shona Robison, Minister for Public Health, said:

“When it comes to alcohol consumption, Scotland is worryingly close to the top of the international league table. Sales data from the alcohol industry itself indicates that we’re buying and drinking much more than people in the other UK countries and most of the rest of the world.

“There can be little doubt that this is largely a consequence of the big fall in alcohol’s relative price, which has dropped 70 per cent since 1980. Significantly, we now buy two-thirds of our alcohol from supermarkets and shops, rather than in pubs and clubs. In these contexts, alcohol is frequently sold as a ‘loss leader’, with heavily discounted deals and pocket-money prices the norm. The sad knock-on of all this has been a huge rise in all types of alcohol-related illnesses and deaths, with Scotland’s liver cirrhosis rate one of the fastest-growing worldwide and double that of England and Wales. Health experts are now agreed that alcohol misuse is the most pressing public health issue facing Scotland and we have to get to grips with it. Deluding ourselves that over-consumption of alcohol across our society is consequence free, or someone else’s problem, is no longer an option.”

Scottish alcohol death rates up to six times UK average

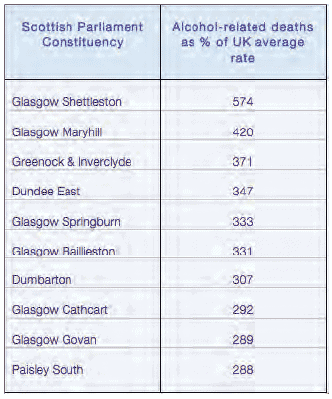

Not surprisingly, Scotland’s high level of alcohol consumption is accompanied by a high death toll from alcohol.

Death rates in one constituency – Glasgow Shettleston – are nearly 6 times the UK level or 574% of the UK average.

In the view of Alcohol Focus, Scotland, the figures, revealed in a Parliamentary Answer by Health Secretary Nicola Sturgeon, add to the case for the Scottish Parliament to introduce serious measures to address Scotland’s relationship with alcohol and support the proposals put forward by the Scottish National Party to crack down on cheap alcohol. “The Scottish Government is proposing radical action to tackle Scotland’s problems with alcohol, but it is also for each and every one of us to think about what we’re drinking and the effect that has on ourselves and public services. “Alcohol misuse costs Scottish society £2.25 billion a year. Recent reports estimating that 30% of ambulance journeys are alcohol-related put the cost to the ambulance service at £30 million – today’s figures show it could be much more than that. “At the start of Alcohol Awareness Week I would urge everyone to look at their relationship with alcohol, how much they drink, and the impact it is having on their lives and on their communities.” The ten constituencies with the highest number of deaths as a percentage of the UK death rate (approx 13 deaths per 100,000) are shown in the accompanying box. Of the 73 Scottish Parliament constituencies, 64 of them have alcohol-related death rates above the UK average and all but one health board has an alcohol-related death rate above the UK average. Amongst health boards, Greater Glasgow and Clyde recorded the highest number of alcohol-related deaths at 267% or nearly three times the UK average.

Jack Law, Chief Executive of Alcohol Focus Scotland said: “These shocking figures highlight the links between alcohol misuse and poverty. Although people from across the social spectrum are affected by personal alcohol problems, people in areas of deprivation suffer greater health and social inequalities as a result of problem drinking.

“Too many communities in Scotland are blighted by alcohol problems. We want to see action on the price of alcohol and its availability – the lure of deeply discounted alcohol comes at a huge cost to families, communities, and services.

“Introducing minimum pricing will make a real difference to alcohol-related harm in Scotland.”

Most night-time Scottish Ambulance call-outs due to alcohol

Figures from the Scottish Ambulance Service, reported on the BBC on the first day of Scotland’s Alcohol Awareness Week in October 2009, show that 68% of calls between Friday night and Sunday morning are alcohol-related. Glasgow SNP MSP Anne McLaughlin who recently joined an ambulance crew in Glasgow on a Saturday night said the figures matched what she had seen:

“Spending the night working with Glasgow’s paramedics showed me how much of their time is spent dealing with the impact of alcohol.

“Whether it is people hurting themselves in drink-related accidents, ending up so drunk they need hospitalization, or the end result of alcohol-induced violence, all the cases we saw on a Saturday night shift involved alcohol.

“I want our emergency services to be dealing with people who really need them, not having to spend all their time mopping up the damage caused by alcohol.

“The Scottish Government is proposing radical action to tackle Scotland’s problems with alcohol, but it is also for each and every one of us to think about what we’re drinking and the effect that has on ourselves and public services.

“Alcohol misuse costs Scottish society £2.25 billion a year. Recent reports estimating that 30% of ambulance journeys are alcohol-related put the cost to the ambulance service at £30 million – today’s figures show it could be much more than that.

“At the start of Alcohol Awareness Week I would urge everyone to look at their relationship with alcohol, how much they drink, and the impact it is having on their lives and on their communities.”

Yet another sensible drinking campaign launched

October 2009 saw the launch of the ‘Campaign for Smarter Drinking’, the latest attempt to persuade young adults not to binge drink.

The campaign, billed as being funded to the tune of £100 million over five years, is being implemented in England in conjunction with the Drinkaware Trust and with the support of the Department of Health. Forty-five drinks producers and retailers are involved in the campaign, which will “offer practical tips to make sure good times don’t go bad, such as reminders to drink water or soft drinks, eat food and plan to get home safely.” The campaign claims it will take a social marketing approach to “use outdoor advertising, signs, drink mats in pubs and bars, on-drink and point of sale displays in retailers to deliver its message.”

Critics claim that on the face of it, the campaign appears to add little to previous efforts. There has been an assortment of responsible drinking campaigns over recent years, funded by a range of government departments as well as industry-funded organisations. Drinks industry giant Diageo launched its own responsible drinking website, and there have been a number of Home Office campaigns alongside the £10 million NHS Know Your Limits campaign.

Interestingly, Sainsburys have refused to participate in the latest effort precisely on the grounds that it merely duplicates other educational initiatives that are already taking place.

However, some public health bodies have made even harsher criticisms, claiming not only that such campaigns are a waste of money but also that the campaign for smarter drinking is little more than a ploy by the drinks industry to head off the threat of mandatory controls on the retailing of alcohol.

Professor Ian Gilmore, Chair of the UK Alcohol Health Alliance and President of the Royal college of Physicians, commented:

“There is very little evidence that health messages work to prevent binge or harmful drinking. Instead, all the international evidence shows that increasing the price and reducing the availability of alcohol, together with bans on advertising, are the main methods of reducing alcohol-related harm. We need strong government action in these areas right now.” Was the Mandatory Code doomed anyway?

Alcohol Concern’s Don Shenker went further, describing the campaign as “yet another example of the drinks industry trying desperately to avoid mandatory legislation. ‘We’ve seen this before from the industry,” he said. “There was a big fanfare when Drinkaware was launched but the money never materialised.”

He added that the campaign’s budget had been calculated at ratecard and through in-kind payments, and as a result the funding was not nearly as great as it sounded. Shenker’s view appeared to be given support by an unnamed drinks industry informant who was reported in a trade journal as agreeing that the purpose of the campaign was to avoid a mandatory code of practice. “The industry has been told by government that if you cough up, we won’t introduce it,’ said the source.

This may have been a reference to a letter from Health Secretary Andy Burnham to the Campaign for Smarter Drinking’s Director, Richard Evans. In the letter, Burnham states that the new campaign plans to make extensive use of point-of sale, advertising and on pack communication and therefore any new mandatory messaging requirements for these media….could potentially conflict with the (new campaign’s) messages and therefore potentially confuse consumers, as well as competing for space in media where space is physically limited.” Burnham goes on to say that the Government therefore wishes to give the new campaign the opportunity to prove its effectiveness before bringing in any mandatory messaging requirements. As the new campaign is scheduled to run for 5 years, that appears to rule out any mandatory code for at least that period of time.

Dangers of unsupervised youth drinking

More evidence of the importance of parental awareness and supervision of their children’s alcohol consumption, and of the dangers of unsupervised youth drinking, has been provided by a major new study by a research team led by Professor Mark Bellis at the Centre for Public Health in Liverpool.

The study of just under 10,000 15- and 16-year olds in the north west of England, a region with particularly high levels of alcohol consumption and harm, found that likelihood of binge drinking and also of harm from drinking was substantially higher in children who drank outside the family environment in parks, streets or other public places compared with those whose access to alcohol was through their parents.

The findings were widely misreported in the media, notably the BBC, as showing that parents should provide their teenage children with a weekly allowance of alcohol. However, lead author Mark Bellis refuted this, pointing out that the report contained no such recommendation. He said that one of the most striking findings of the study was that adverse effects of drinking were common even in children who drank relatively small amounts in the family home. Bellis said:

“Regretted sex after drinking, having been involved in violence when drunk, consuming alcohol in public places and forgetting things after drinking had all been experienced by relatively large proportions of teen drinkers. For children who drink alcohol we did not find any typical drinking patterns where children were at no risk of harms. Accessing alcohol through parents did not remove the risks of alcohol related harms but was associated with lower levels of risk”. While 19.9% of teen drinkers whose parents provide alcohol and who drink once a week had been involved in violence when drunk, this rose to 35.9% in those who only access alcohol through other means.

Another notable finding of the study was that problems from youth drinking are strongly associated with the types of alcohol consumed. Those who consumed multi-litre value cider bottles, spirits and other cheap forms of alcohol reported higher frequency of violence when drunk, and alcohol-related sexual encounters that they later regretted compared with those who had consumed other products. Interestingly, alcopops were not associated with higher levels of adverse effects. Bellis concluded: “The negative impacts of alcohol on children’s health are substantial. Those parents who choose to allow children aged 15-16 years to drink may limit harms by restricting consumption to lower frequencies (e.g. no more than once a week) and under no circumstances permitting binge drinking. However, parental efforts should be matched by genuine legislative and enforcement activity to reduce independent access to alcohol by children and to increase the price of cheap alcohol products”.

Scottish children besiege Childline over parental drinking

New research reveals that a high number of calls to ChildLine from young people concerned about their parents harmful drinking come from children in Scotland compared to the rest of the UK.

The study carried out by ChildLine and SHAAP highlights children’s accounts of the severe negative impacts of harmful parental drinking on their lives including emotional stress, physical abuse and neglect.

Dr Evelyn Gillan, Director of Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems and co-author of the study added: “We know that increased alcohol consumption in Scotland is driving an increase in health and social harm but what is often not acknowledged is the harm this causes to people other than the drinker.

“It’s likely that people drinking harmfully will negatively affect the lives of two other close family members. What this study shows is that many of those negatively affected by someone else’s drinking are children and the direct impact on their lives includes an increased risk of physical violence and abuse, severe emotional distress and neglect. What is particularly sad, is that many children experience a loss of childhood because they often take on caring responsibilities such as looking after brothers or sisters and this can prevent children doing normal childhood activities.”

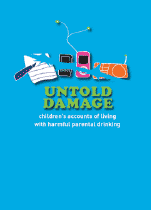

Untold Damage – children’s accounts of living with harmful parental drinking – Wales, A; Gillan, E; 2009

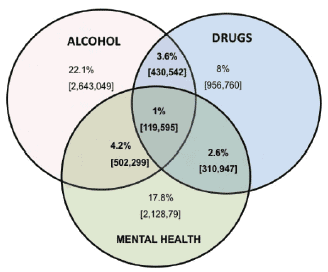

Numbers of children of substance abusing parents

Almost 1 in 3 children live with a binge drinking parent. Widespread patterns of binge drinking and recreational drug use have resulted in higher numbers of children in the UK than previously thought being exposed to sub-optimal care and substance-using role models.

This is the conclusion of a new study to estimate the numbers of children aged under 16 exposed to parental substance abuse.* Deriving estimates from UK national household surveys of alcohol and drug use and the prevalence of psychological disorders, the researchers calculate that around 700,000 children live with a parent who is dependent on alcohol, and up to 3.6 million with at least one parent who is a binge drinker. Just under 1 million children live with a parent who has used an illegal drug during the last 12 months.

The detailed estimates are shown in the box below. However, the researchers say that the situation is not universally bleak, despite these figures. Research findings also indicate that the most high-risk drug-taking behaviours tend to exist among parental substance misusers physically separated from their children, thus eliminating direct negative effects. Moreover, while parental substance misuse can impair parenting capacity, harm is not inevitable and indeed, the authors say, rarely exists in isolation from other factors such as poverty, social exclusion, poor housing and family tension.

Alcohol:

- 3.3 – 3.5 million (30% of total) in the UK live with at least one binge drinking parent

- 8% (978000) with two binge drinkers

- 4% (500000) with one binge drinking parent

- 2.6 million live with a ‘hazardous’ drinker

- 6% (705000) with an alcohol dependent drinker

Drugs:

- 978000 (8%) lived with at least one adult who had used illegal drugs during that year

- 2% (256000) with class A drug user

- 7% (873000) live with a Class C drug user

- 335000 live with a drug dependent parent

- 72000 live with an injecting drug user

- 72000 live with a drug user in treatment

- 108000 live with an adult who had overdosed

Alcohol and Drugs:

- 3.6% (430000) lived with a problem drinker who also took drugs

- 4% (500000) lived with a parent who had alcohol problems coexisting with other mental health problems

*Manning, V et al 09; New estimates of the number of children living with substance misusing parents: results from UK national household surveys: BMC Public Health 2009, 9:377

Moves to provide greater protection for children living with alcohol and drug dependent parents

The children of parents dependent on alcohol or other drugs will get special help if they are at risk when their parents are receiving treatment, under a new agreement between the National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse (NTA) and the Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF). New guidance issued to local social services makes clear that drug and alcohol treatment workers can help children’s services identify vulnerable children and families.

For the first time, local protocols will spell out the important role that drug workers can play in delivering a child protection plan:

Information about the risk of harm

Specialist advice on how the parents’ addictive behavior may affect the child’s safety

Securing improvements in the health and social functioning of parents

The guidance entitled Joint Guidance on Development of Local Protocols between Drug and Alcohol Treatment Services and Local Safeguarding and Family Services, published jointly by the NTA and DCSF, makes explicit to all staff working with families that referrals should be made to children’s services when a child is suspected of suffering significant harm.

This builds on the statutory duty of section 11 of the Children’s Act 2004 which ensures that protecting a child from harm has to be the paramount concern of all agencies.

Paul Hayes, NTA Chief Executive, launched the initiative at a ‘Think Families’ conference. He said: “Drug workers are not child protection or safeguarding experts, but their role in providing effective treatment to drug dependent individuals means identifying the influences on an adult’s drug use and what motivates them to stop. Questioning what’s happening within the families of drug users in treatment is critical for successful treatment outcomes, both for the individual as well as any family involved, and the new guidance for local protocols clarifi es when and how to involve children’s social care. Entering drug treatment is protective: it protects the individual, their children and wider society.”

Alongside the guidance, the NTA is releasing figures from the National Drug Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS) which have been collected from the 83,000 adults newly presenting to treatment in 2008/09.

These show:

- 39,156 adults newly entering drug treatment in England in 2008/09 are parents who may not be living with children but may have access to them periodically

- 27,670 adults newly entering drug treatment in England in 2008/09 are living in a household with children

- 48,703 children are living in the same home as someone newly entering drug treatment in England in 2008/09

On this basis the NTA estimates that at least 120,000 children are living with the 207,000 adult drug users in England’s total treatment population.

Access to treatment will enable many drug-misusing parents to care for their children well. These protocols are designed to maximize the proportion of drug-using parents who can look after their children, while minimizing the risk of harm to the children of those who cannot, through early identification and prompt intervention.

The Think Families agenda is led by the DCSF and supported by the NTA in delivering safeguarding guidance to the drug treatment sector in England.

Cot death alcohol link

More than half of sudden unexplained infant deaths occur while the infant is sharing a bed or a sofa with a parent (co-sleeping) and may be related to parents drinking alcohol or taking drugs, suggests a study published in the on-line version of the British Medical Journal. Although the rate of cot death in the UK has fallen dramatically since the early 1990s, specific advice to avoid dangerous co-sleeping arrangements is needed to help reduce these deaths even further, say the researchers.

The term sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) was introduced in 1969 as a recognised category of natural death that carried no implication of blame for bereaved parents. Since then, a lot has been learnt about risk factors, and parents are now advised to reduce the risk of death by placing infants on their back to sleep, in the “feet to foot” position at the bottom of the cot, and keeping infants in a smoke-free environment. But it is not clear which risk messages have been taken on board in different social or cultural groups, and little is known about the emergence of new or previously unrecognised risk factors.