In this month’s alert

Editorial – January 2018

Welcome to the November 2017 edition of Alcohol Alert, the Institute of Alcohol Studies newsletter, covering the latest updates on UK alcohol policy matters.

This month, an Alcohol Health Alliance commissioned survey finds that only 16% people are aware of the weekly alcohol guidelines and only one in ten people know of the established links between alcohol and cancer. Other articles include: a promise of a helpline from the Health Secretary to NACOA; Diageo pirate character forced off social networking site; a row breaks out between public health charity and industry funded body in the aftermath of an alcohol labelling report.

Please click on the article titles to read them. We hope you enjoy this edition.

TOP STORY – Awareness of drinking guidelines remains low

UK government and alcohol industry ‘failing to provide drinkers with the information they need’ – AHA

Only 1 in 10 people know of the established links between alcohol and cancer |

10 January – An Alcohol Health Alliance UK (AHA) commissioned survey shows that only 16% people are aware of the weekly alcohol guidelines, two years after the guidelines were announced.They also reveal that parents are not equipped with the right information to keep their children safe from alcohol harm, with fewer than one in twenty aware of the official advice on children’s drinking. OnePoll were commissioned by the AHA to survey 2,000 people across the UK on their attitudes to alcohol in September 2017. The headline statistics were:

- Only 16% of people are aware of the low-risk weekly drinking guideline of 14 units

- Only 3% of people are aware of the guidance that an alcohol-free childhood is best

- Only 10% of people mention cancer when asked which diseases and illnesses are linked to alcohol

The statistic on cancer is of particular interest, given that alcohol is known to be linked with at least seven types of cancer, and has been classed as a class 1 carcinogen – on a par with tobacco – by the International Agency for Research on Cancer. The alcohol industry has been found to mislead the public on this link, by denying or distracting away from it: in Canada, representatives for the industry recently lobbied successfully to have a trial of cancer labels on alcohol products halted.

Speaking to The Guardian, Cancer Research UK’s cancer prevention expert Professor Linda Bauld expressed concern over the ‘scale of ignorance’ about cancer’s association with drinking.

’Alcohol is a major cause of cancer but this survey clearly shows that the vast majority of people don’t know this, which is very worrying,’ she said.

An appetite for better alcohol education

Whilst awareness of the alcohol guidelines for both adults and children is low, the survey found that there is an appetite among the public for greater information on the risks linked with drinking, with high levels of support for the inclusion of warning messages on alcohol labels:

- 81% believe the weekly guidelines should appear on alcohol labels

- 78% believe labels should include a warning that exceeding the guidelines can damage your health

- 77% of people support a cancer warning on alcohol product labels

- 73% believe labels should include calorie information

- 55% of people believe that ‘providing children with alcohol in a supervised situation will ensure that they know how to handle drinking when they’re older’

- 57% of people believe that ‘children that drink alcohol in moderation with their own family are less likely to binge on their own’

- 77% of people believe that the UK has an ‘unhealthy’ relationship with alcohol

- 52% think that the government is not doing enough to tackle the problems with alcohol in society.

What are the facts?

The low-risk weekly drinking guideline for adults is 14 units a week – around six pints of 4% beer, or six medium glasses of wine. This guideline was announced by the UK’s Chief Medical Officers in January 2016.

For children, the official advice is that an alcohol-free childhood is best, due to evidence of a wide range of short term and long term harms linked to children’s drinking. In England, the Chief Medical Officer says that if children do try alcohol, they should be at least 15 years old, and be in a supervised environment.

The recommendation that an alcohol-free childhood free is best is based on the fact that young people are physically unable to tolerate alcohol as well as adults, and young people who drink are more likely to engage in unsafe sex, try drugs, and fall behind in school.

In addition, the younger someone starts drinking, the more likely they are to develop a problem with alcohol when they are older. This goes against the commonly held view that allowing children to drink at home at a young age will teach them to be responsible drinkers when they are adults. The AHA survey found that this view was common, with 55% of those surveyed agreeing that children who drink at home will ‘know how to handle their drink when they’re older’, and that children who drink in moderation at home ‘are less likely to binge on their own.’

Commenting on the results of the AHA’s polling, Professor Sir Ian Gilmore, chair of the AHA, said that more should be done to ensure the guidelines for both adults and children are communicated to the public. He said:

‘It is really disappointing that only 16% of the public are aware of the alcohol guidelines for adults, and that fewer than 1 in 20 are aware of the advice around children’s drinking.

‘The public have the right to know the Chief Medical Officers’ guidelines, so that they are empowered to make informed choices about their drinking. The same applies to parents, who want to do the right thing by their children and deserve to be informed of the Chief Medical Officers’ guidance on children and alcohol.

‘It is clear from our polling that the public want to be informed of the risks linked with alcohol, including the link with cancer, and that they want to see clear warning information on alcohol labels about the drinking guidelines and the risks of drinking at levels above these guidelines.

‘To this end, the government should introduce mandatory labelling of all alcoholic products, to ensure that the public and parents are fully informed about the risks.

‘In addition, the government should develop national information campaigns, informing the public and parents of the guidelines for both adults and children.’

Knowledge of old guidelines also lacking

The AHA survey was followed by a separate investigation into the public knowledge and use of the old UK drinking guidelines, published in Alcohol and Alcoholism. Researchers gathered a demographically representative, cross-sectional online survey of 2,100 adults living in England in July 2015 – that is, two decades after adoption of previous guidelines and prior to introduction of new guidelines.

They found that, despite previous guidelines being in place for two decades, only one in four drinkers accurately estimated these, with even fewer using guidelines to monitor drinking. Furthermore, roughly 8% of drinkers overestimated maximum daily limits.

‘Two decades after their introduction, previous UK drinking guidelines were not well known or used by current drinkers. Those who reported using them tended to overestimate recommended daily limits,’ they concluded.

You can listen to Colin Shevills of Balance North East talk about the survey on our podcast by clicking on the Soundcloud link below.

National helpline for children of alcoholics ‘on the way’

Health secretary – move ‘transcends party politics’

01 January – Secretary of State for Health Jeremy Hunt MP has pledged to include a national helpline to support 200,000 children being raised by alcoholic parents in a new strategy, after being moved by the personal story of his Labour counterpart.

Hunt praised what he said was the extraordinary bravery of his opposite number Jonathan Ashworth MP, who spoke out about his upbringing in an interview with The Guardian a year ago. Ashworth, the shadow health secretary, also described how he would return home to a fridge stacked with cheap alcohol and no food.

Now the government is committing £500,000 to expand an existing local support line for children into a national helpline.

The pledge comes as the National Association for Children of Alcoholics (NACOA) received 36,000 emails and phone calls last year. It said its helpline counsellors had read bedtime stories to five-year-olds because their parents were too drunk to pay them attention at night.

The MP for Leicester South said that Hunt’s commitment to work on a cross-party basis to produce a strategy including a national helpline was ‘a victory to all those who supported our campaign as well as MPs like Liam Byrne and Caroline Flint who have also spoken out so bravely’. Looking ahead, Ashworth promised to engage with ministers to ensure that ‘this absolutely crucial and welcome announcement’ was fully backed up.

Alcohol acts as catalyst for hate crime injuries

Victims cite drunkenness as reason for majority of violent incidents

01 January – Nine out of every ten hate crimes resulting in injuries to hospital emergency departments are caused by alcohol, according a new study from Cardiff University.

Published in the journal of Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, ‘Injury resulting from targeted violence: An emergency department perspective’ especially found a strong link between drunkenness and violence based on race, religious or sexual orientation.

The research team conducted a small n study comprising interviews with 124 people who had sought emergency treatment at hospitals in Cardiff, Blackburn and Leicester following violent attacks.

They found that nearly a fifth (23, 18.5%) of the injured patients considered themselves to have been attacked by others motivated by hostility or prejudice to their ‘difference’ (targeted violence), thematic analyses indicating that these prejudices were down to: appearance (seven cases); racial tension (five cases); territorial association (three cases); and race, religious or sexual orientation (eight cases).

According to victims, alcohol intoxication was particularly relevant in targeted violence (an estimated reported frequency 90% and 56% for targeted and non-targeted violence, respectively).

Discussing their findings, the authors of the study warned against drawing too many conclusions from the small sample size of data. According to official annual statistics, 2016/17 saw the largest percentage increase in hate crimes since the series began in 2011/12, which has in part been driven by ‘improvements in police recording’.

However, they also noted that many respondents felt that the link between alcohol intoxication and hate was so strong that violent behaviour was inevitable in these circumstances.

‘Limiting alcohol consumption was viewed by many of those injured in targeted and hate violence as a strategy to reduce the risk’, they wrote.

Speaking to Pink News, professor Jonathan Shepherd of the Cardiff University Crime and Security Research Institute says that the research suggests that being drunk can act as an ‘igniter’ for people’s racist and homophobic prejudice.

He explained: ‘A striking aspect of the study was the discovery that most attacks weren’t fuelled by hate alone; alcohol appeared to act as an igniter.

‘Our findings suggest that tackling alcohol abuse is not only important in regards to the health of individuals but also to the health of our society.

‘Additionally, we have learned that emergency room violence surveys can act as a community tension sensor and early warning system.’

Poorest drinkers suffer from heart disease

Study finds association between impacts of alcohol consumption and social background

02 January – The risk of cardiovascular mortality is highest for drinkers of a low socioeconomic position (SEP), according to Norwegian researchers in PLoS Medicine, but the reasons for this are unclear.

Their findings came from three cohort surveys from 1987 to 2003 containing data about the drinking habits of more than 200,000 Norwegians born before 1960, which sought to observe socioeconomic differences in risk estimates of cardiovascular mortality (death rates from heart disease) associated with given alcohol consumption levels.

The results showed that the risk of deaths from heart disease was lower amongst moderately frequent drinkers [2–3 times per week] than infrequent drinkers [once per month to once per week], but when stratified by life course SEP, the risks of all-cause mortality (including heart disease) were even lower among moderately frequent drinkers with a high SEP than those with lower SEPs, and only very frequent drinkers [4–7 times per week] of a low SEP suffered an increased risk of death from heart disease.

Furthermore, weekly binge drinkers [at least five drinks per occasion] of all SEPs had a higher risk from dying of cardiovascular disease than current drinkers who did not binge drink.Set against the fact that although poorer income groups were found to be more likely to abstain or drink less frequently than their wealthier counterparts, they were more exposed to all other CVD risk factors at the same consumption levels, the researchers admitted that they could not ascertain whether it was alcohol or something else in their lifestyle that increased the risk.

Speaking to Science Nordic, Eirik Degerud, a postdoc at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, who was also led the study, said: ‘It may be that this link is not due to the alcohol itself, but lifestyle.”Both diet and mental health may possibly have an effect,’ he also suggested.

Captain Morgan forced off Snapchat

Ad regulator forces Diageo character to walk the plank

03 January – Diageo has removed all of its advertising from image-sharing app Snapchat globally, in light of the UK Advertising Standards Authority’s (ASA) decision to ban an advert starring the drinks giant’s Captain Morgan character for appealing to children.

Last summer, the rum brand introduced a Snapchat lens filter which made a user’s face look like the cartoon version of the pirate icon, and featured two glasses of a mixed alcoholic drink clinking together on screen, a seagull that flew a scroll on to the screen, which read “Live like the Captain”, plus a voice-over that said “Captain” to the sound of people cheering.

The ASA challenged whether the lens was: of particular appeal to people under 18; and directed at people under 18.

Considering the potential appeal of the ad to children viewing it on Snapchat, the ASA stated that ‘a significant minority of UK based Snapchat users were registered as being between 13 and 17 years old’, remarking that the app was popular amongst younger audiences.

The regulator also noted that at the time the lens ran, the only targeting data available to Diageo on Snapchat was unverified supplied ages collected when users signed up and geolocation information. Therefore, the rum brand had not taken sufficient care to ensure that the ad was not directed at people under 18.

In its submission to the ASA, Diageo denied bright, loud or artificial colours that would be of particular appeal to people under the age of 18. Diageo also insisted that the Captain Morgan lens used age-gated targeting to ensure that it was only delivered to users with a registered age of 18 years and over, and that they were confident in the reliability and sufficiency of the ages supplied to them during the sign-up process.

However, the ASA upheld its complaint on the grounds that the advert could still reasonably be understood to appear to appeal to children, with the advert’s reach running the risk of breaching the Committees of Advertising Practice Code (Edition 12) rule (Alcohol), which states that no medium should be used to advertise alcohol if more than 25% of its audience is under 18 years of age.

As a result, Diageo was instructed to no longer broadcast the ad in its current form.

Responding to the judgment, a Diageo spokesperson said: ‘We have a strict marketing code, take our role as a responsible marketer very seriously and acknowledge the ASA’s ruling. We took all reasonable steps to ensure the content we put on Snapchat was not directed at under-18s — using the data provided to us by Snapchat and applying an age filter.

‘We have now stopped all advertising on Snapchat globally whilst we assess the incremental age verification safeguards that Snapchat are implementing.’

According to CNBC, Diageo’s move to leave Snapchat could prove to be a blow to the social media platform’s fortunes. The drinks-maker spent £1.798 billion ($2.438 billion) on all marketing in 2017.

Weekly spending on alcohol creeps upwards

Northern Irish families’ spending patterns fall in line with other Home Nations

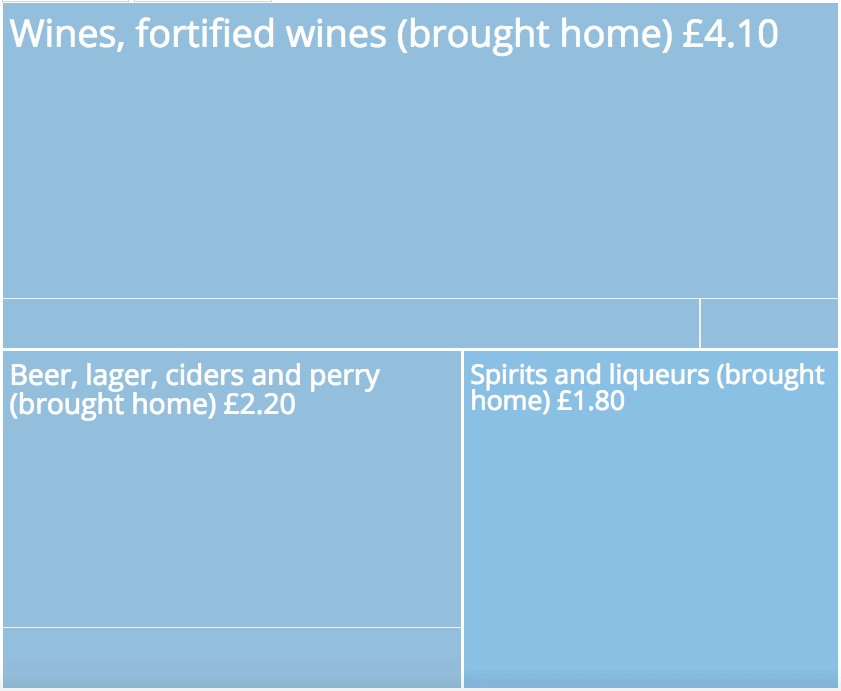

Household spending on alcoholic beverages by type |

18 January – UK households’ weekly spending on alcoholic beverages has increased slightly, according to the latest data from the Office for National Statistics.

The statistical authority’s release, which gives an ’insight into the spending habits of UK households’, found that in the financial year to 2017, UK households spent an average of £8.20 per week on alcoholic beverages for domestic consumption (illustrated), of which:

- £4.10 was spent on wines (including fortified wines);

- £2.20 on beer, lager, ciders and perry; and

- £1.80 was spent spirits and liqueurs.

Based on three-year averages, UK household spending on alcohol brought home was slightly lower, at £8 per week. Combined with that spent outside the home (£7.50 per week), UK household expenditure on alcohol represented roughly 3% of total household spending for the financial year to 2017. UK household spending on alcohol is up slightly on the previous financial year, when the average UK family spent £7.90 on alcoholic beverages brought home and £7.30 on those drinks consumed away from home.

In their report, the ONS observed that the level of spending has returned to 1950s levels:

‘Spending on alcohol has risen and then declined over the 60-year period. In 1957, the proportion of total expenditure on alcohol was 3%, before rising to 5% in the 1970s and 1980s. This then declined, with the most recent data showing that the proportion of total expenditure on alcohol was 3%; the same as 1957.’

When broken down by region, the other Home Nations’ outlook largely matched the overall UK outlook, with the notable exception of Northern Irish families, whose spending habits on alcohol away from home in the last two financial years dovetailed dramatically against the biggest increase of all Home Nations for alcoholic beverages brought home (link). The average Northern Irish family spent 50p more on alcohol brought home, compared with £1.70 less on alcohol spent outside it.

Drinking in late teens can lead to liver problems in adulthood

Current guidelines for safe alcohol intake in men might have to be revised, researchers warn

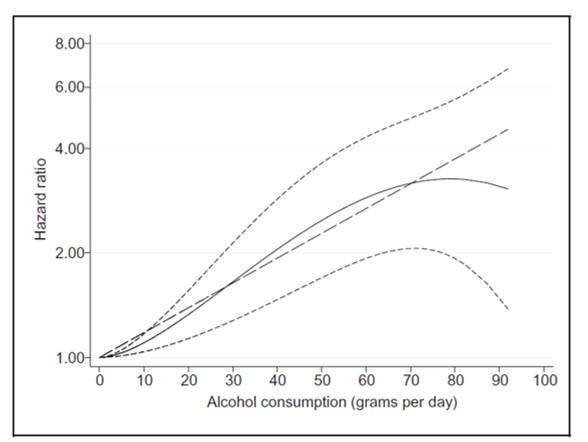

Hazard ratios by consumption level |

22 January – Results of a large long-term study in Sweden have confirmed that drinking during late adolescence could be the first step towards liver problems in adulthood and that guidelines for safe alcohol intake in men might have to be revised downwards, reports the Journal of Hepatology.

Current recommended cut-off levels in some countries suggest that safe alcohol consumption for men to avoid alcoholic liver disease is 30 grams per day, roughly equivalent to three drinks. ‘Our study showed that how much you drink in your late teens can predict the risk of developing cirrhosis later in life,’ explains lead investigator Hannes Hagström, MD, PhD, of the Centre for Digestive Diseases, Division of Hepatology, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden. ‘However, what can be considered a safe cut-off in men is less clear.’

Investigators conducted a retrospective study to assess the association between alcohol consumed early in life with later development of severe liver disease. The study involved using the data of roughly 43,000 Swedish men in their late teens enlisted for conscription in 1969–1970 (during this period, conscription was mandatory in Sweden). Results were adjusted for body mass index, smoking, use of narcotics, cognitive ability, and cardiovascular capacity.

After almost 40 years of follow-up, they found that alcohol consumption was a significant risk factor for developing severe liver disease, independent of confounders. A total of 383 men had developed severe liver disease, which was defined as a diagnosis of liver cirrhosis, decompensated liver disease (hepatocellular carcinoma, ascites, esophageal varices, hepatorenal syndrome, or hepatic encephalopathy), liver failure, or death from liver disease. This risk was dose-dependent, and was most pronounced in men consuming two drinks per day or more.

‘If these results lead to lowering the cut-off levels for a “safe” consumption of alcohol in men, and if men adhere to recommendations, we may see a reduced incidence of alcoholic liver disease in the future,’ says Dr. Hagström.

4% of population drink one-third of alcohol sold in England

Joint committee heard evidence during parliamentary debate

Panel of witnesses at the committee hearing |

23 January – Just 4% of the population consume almost a third of all the alcohol sold in England, according to Public Health England.

The figures emerged during a three-hour oral evidence session assessing the case for introducing a minimum unit price (MUP) on alcohol in England, jointly held by the Health Committee and Home Affairs Committee.

Rosanna O’Connor, director of alcohol, drugs and tobacco at Public Health England (PHE) told MPs: ‘Around 4.4% of the population are drinking just under a third of the alcohol consumed in this country. That’s around 2 million drinking just over 30% of the alcohol.’

The numbers mentioned by O’Connor originally appeared in the Public Health England’s review into the public health burden of alcohol, published in December 2016. They were supported by University of Sheffield modelling into the impact of MUP at 60 pence per unit, which she said would result in:

- 3,000 fewer deaths over five years

- 88,000 fewer admissions

- 350,000 fewer alcohol-related crimes

- 1,068,000 fewer days off from work

Another panel witness, professor and Head of Clinical Hepatology within Medicine at the University of Southampton, Nick Sheron, suggested that the modelling might be ‘underplaying the true impact of MUP’, as it plugged in conservative numbers.

‘I wouldn’t advise delaying because the human cost is considerable,’ Sheron warned.

Half of 14-year-olds have tried alcohol

Adapted from The Centre for Longitudinal Studies press release

24 January – Just under half of young people in the UK had tried alcohol by the time they were 14, with more than one in ten confessing to binge drinking, new findings from the Millennium Cohort Study have revealed.

Researchers at the Centre for Longitudinal Studies, part of the UCL Institute of Education, examined data collected from more than 11,000 14-year-olds about their experiences of a range of different risky activities, including drinking, smoking and drug-taking.

Study participants, whose lives have been tracked through the Millennium Cohort Study since they were born at the turn of the century, had previously been asked about drinking and smoking when they were 11.

Comparing their answers at age 11 and at age 14, revealed big increases in binge drinking rates (having five or more drinks at a time on at least one occasion): Under 1% had been binge drinking by age 11, compared to almost 11% at age 14.

Comparing similar boys and girls, boys were more likely to have started drinking at a younger age than girls; 20% of boys had drunk alcohol by the time they were 11, compared to 14% of girls.

Interestingly, in the main, parents’ education neither increased nor decreased the odds of their teenage children drinking.

Professor Emla Fitzsimons, one of the authors of the research and director of the Millennium Cohort Study, said: ‘Our findings are a valuable insight into health-damaging behaviours among today’s teenagers right across the UK. There is clear evidence that substance use increases sharply between ages 11 and 14, and that experimentation before age 12 can lead to more habitual use by age 14. This suggests that targeting awareness and support to children at primary school should be a priority. Our analysis also highlights the groups most vulnerable to being drawn into substance use who may benefit from additional support.’

Drink Wise, Age Well on Vintage Street

Film raises awareness of older people’s drinking habits

24 January – Drink Wise Age Well has released a short film that seeks to raise awareness of the reasons alcohol use can increase as people get older we can hopefully create more empathy and reduce the stigma that can be a barrier to seeking help.

Vintage Street (video free to view here) follows the activities of older couples in a local neighbourhood setting, whilst drawing attention to their drinking habits.

It comes as part of a campaign dedicated to generating a better understanding of the life transitions that can lead some older adults to drink more and ultimately prompt their family, friends, partners and peers to reach out and offer help.

The charity aims to help people aged over 50 make healthier choices about alcohol. The programme exists because harmful use of alcohol is declining across the whole population but increasing among older adults. Whilst there has been much reporting and media coverage on alcohol trends and consumption levels there has been little to explore the reasons why alcohol use can increase as we age.

No evidence that parent-aided drinking protects teens

Helping children to ‘drink responsibly’ may do more harm than good

25 January – Parents who give children alcohol in the belief that it will foster responsible drinking are mistaken, according to a major new study published in The Lancet Public Health.

A six-year analysis of nearly 2,000 schoolchildren and their parents in three Australian cities revealed there were ‘no benefits’ to introducing alcohol to teenagers at home, and that doing so only encouraged them to seek it elsewhere.

The proportion of children who accessed alcohol from their parents rose over the period, from 15% to 57%. The year-on-year increases among schoolchildren who accessed alcohol from both their parents and other sources suggests that teenagers supplied with alcohol by only their parents one year were twice as likely to access alcohol from other sources the next.

At the end of the study, 25% of the teens given alcohol by their parents admitted to binge drinking (defined as consuming more than four drinks on a single occasion). A total of 35% experienced alcohol-related harms.

The rates of self-reported binge drinking and alcohol-related harms among children who obtained alcohol from other sources were 62% and 72% by the end of the study. From both parents and other sources, the rates were 81% and 86% respectively.

The researchers concluded that ‘there was no evidence to support the view that parental supply is protective for any of the adolescent drinking-related outcomes.’

Professor Richard Mattick of the University of South Wales, who led the research, said: ‘Parental provision of alcohol is associated with risk, not with protection.

‘Parents should avoid supplying alcohol to their teenagers if they wish to reduce the risk of alcohol-related harms.’

Alcohol ‘partnership’ breaks down over labelling report

Findings expose rift between Royal Society for Public Health and Portman Group

A mock-up of alcohol labels under RSPH’s proposed new system |

The Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH) has called for a tightening of alcohol labelling of drinks, while the alcohol-industry funded standards body The Portman Group denied that consumers need more information crammed onto packaging. Labelling the Point highlights the contribution that could be made by better alcohol labelling, and recommends a best practice scheme that could help raise awareness and reduce harm (illustrated, right).

The scheme includes:

- Mandatory inclusion of the UK Chief Medical Officers’ low-risk drinking guidelines of no more than 14 units a week (possibly traffic light colour-code style), potentially including an explicit cigarette-style warning of the link with health conditions such as bowel and breast cancer

- A drink drive warning on the front label – RSPH’s research indicates explicit warnings such as these are especially prioritised by young drinkers and more deprived socio-economic groups

- Calorie content per container or per serve on the front label – this could result in an almost 10% swing in consumer purchasing decisions from the highest alcohol drinks to the lowest, within all main drink categories (beers, wines, spirits) and across all socio-economic groups. The effect is particularly pronounced among young (18-24) drinkers, who could switch purchases from high to low alcohol drinks by as much as 20%.

The report was borne out of a survey of 1,800 adults – originally commissioned in partnership with The Portman Group. However, the industry-funded group has moved to make alcohol labels even less informative to the public than they are at present, by releasing new guidance to manufacturers in September 2017 that no longer includes the Government’s low-risk drinking guidelines as a required element. This is in spite of RSPH research showing that alcohol unit information is largely useless to many people unless contextualised by the Government’s guidelines.

In the foreword to the report, RSPH Chief Executive Shirley Cramer CBE expressed her concern that even in the limited arena of labelling, ‘it proved too difficult to reach a consensus position between the agenda of public health and that of industry’. She told the BBC that ‘the potential health consequences of alcohol consumption are more serious than many people realise’.

‘Warnings are now mandatory on most products from tobacco to food and soft drinks, but alcohol continues to lag behind. If we are to raise awareness and reduce alcohol harm, this must change,’ said Cramer.

The health charity accused The Portman Group of no longer being serious about setting a challenge for industry to play their part in informing the public and protecting their health. In a statement, The Portman Group claimed that the findings supported the industry’s approach in developing updated voluntary guidance, and that ‘to suggest otherwise is misrepresentative’.

However, Sir Professor Ian Gilmore of the Alcohol Health Alliance welcomed the report. He said: ‘The decision last year by the Portman Group to weaken their recommendations on what should appear on alcohol labels clearly showed that alcohol producers wish to withhold information on alcohol and health from the public.

‘Their decision not to endorse the findings of this report is yet more evidence that producers cannot be relied upon to communicate the risks linked with alcohol. It is clear from this research that the public want labels to include the drinking guidelines, and we know from our own research that 81% of the public want to see the guidelines on labels. Producers should accept this.

‘Alcohol is linked with over 200 disease and injury conditions, including heart disease, liver disease and at least seven types of cancer. We all have a right to know the drinking guidelines, along with the risks associated with alcohol, so that we are empowered to make informed choices about our drinking. With alcohol producers unwilling to communicate this information, the government should now introduce mandatory labelling of all alcohol products, with labels clearly communicating the guidelines and health risks.’

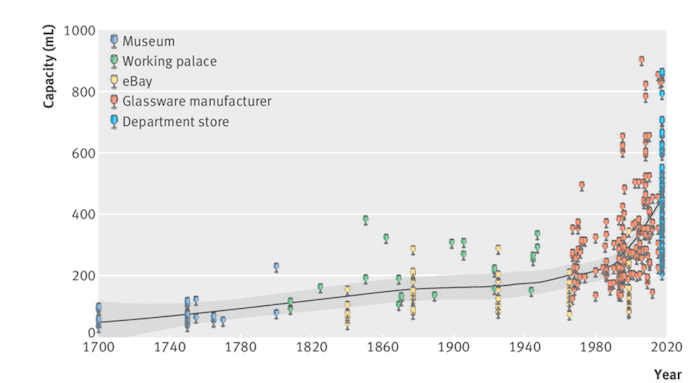

ALCOHOL SNAPSHOT – British wine glasses have got bigger since 1700

Growth in the size of wine glasses may be part of the explanation for increasing wine consumption in the UK over the past 300 years, according to a recent study in the BMJ. The chart above shows how the capacity of wine glasses has changed over time, drawing on a database collated from five different sources by Theresa Marteau and colleagues:

- A collection of 43 18th century wine glasses from the University of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum

- 24 wine glasses commissioned by the Royal Household for each new monarch, dating between 1808 and 1947

- 65 listings on the online auction site eBay, including pieces dating back to 1840

- 180 glasses listed in catalogues from Dartington Crystal between 1967 and 2017

- The 99 glasses sold on the John Lewis website in 2016

The chart demonstrates that wine glasses grew steadily bigger between 1700 and the 1990s, and have expanded at a much higher rate thereafter. The average wine glass held just 66mL in 1700, compared to 449mL today.

While the authors stress that they cannot demonstrate a causal link between wine glass size and consumption, they note that wine consumption has increased over this period. Moreover, they point out that previous research has shown that larger tableware can increase food consumption, and so a similar process may apply to wine: larger wine glasses may influence upwards drinkers’ perception of what constitutes an appropriate serving of wine. This not the first time researchers have drawn a connection between vessel size and alcohol consumption: applications of ‘nudging’ to alcohol policy have led to calls for smaller measures of beer in pubs. In a similar vein, Marteau and colleagues suggest their findings might justify licensing regulations to reduce wine glass sizes in the on-trade.

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

Gambling industry harms and parallels with the alcohol world

Will Prochaska –

Coalition to End Gambling Ads