In this month’s alert

Alcohol Marketing: Explained

IAS is very pleased to launch the third film in its Explained series, which focuses on: Alcohol Marketing.

In this film, we look at:

The expert speakers in the film are Professor David Jernigan (University of Boston), Alison Douglas (Alcohol Focus Scotland), and Dr Amanda Atkinson (Liverpool John Moores University).

Please share with your contacts and on social media. The film will be particularly helpful for those new to the subject.

Dispelling Six Industry Myths About Alcohol Taxation – IAS report

In the run up to every Budget and Autumn Statement, the alcohol industry vociferously lobbies for alcohol duty to be cut or frozen (a real terms cut), yet many of their economic arguments do not stand up to scrutiny.

In this myth buster, we show that uprating duty does not have the cataclysmic effect alcohol industry lobbyists argue it will. During periods of both uprating and freezing:

- Duty revenue into the Treasury continued to increase (see Myth 1).

- Alcohol production and sales remained very stable or grew, with major drinks companies recording massive profits (see Myths 1 and 2).

- Pubs closed at a similar rate (Myth 3).

- Employment numbers in pubs and bars remained remarkably stable (Myth 4).

- And uprating is clearly not regressive when taking health effects into account, a crucial consideration for a public health lever (Myth 5).

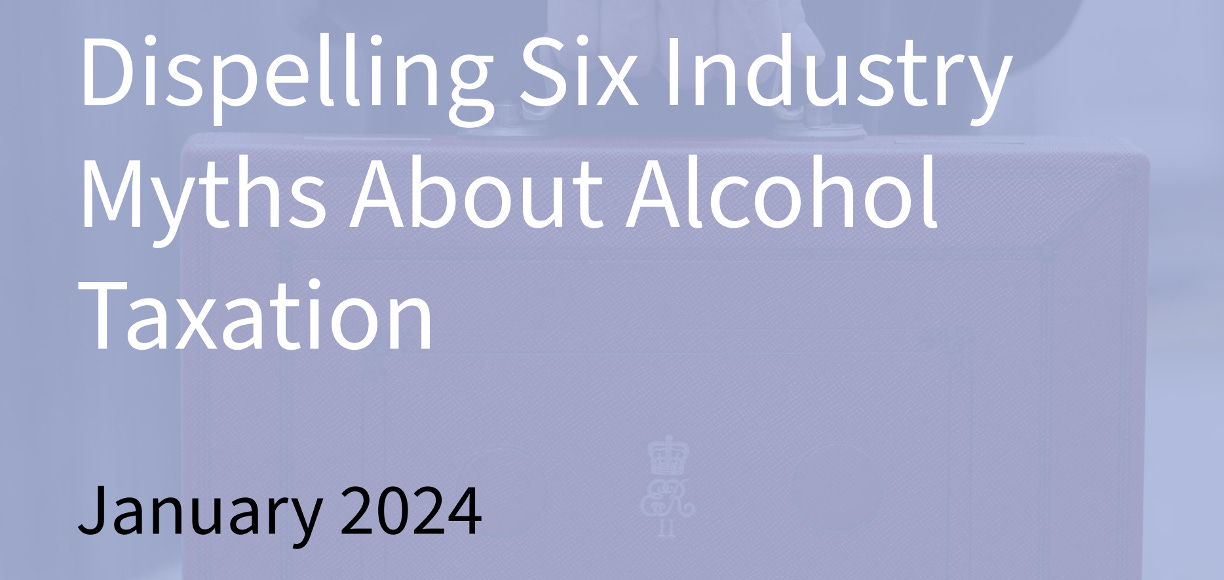

Right on cue, a day after our report was published, the Scotch Whisky Association (SWA) argued that the uprating of alcohol duty in August 2023 lost the Treasury £98 million in revenue. However, the SWA was only comparing August – December 2023 with the same period in 2022, and there is a clear reason why there was such a difference in revenue. As producers knew that duty was to be uprated in August 2023, they cleared far more of their products before that point, to cash in on the lower rates, as this graph demonstrates (spirits-only, but the same can be seen for all products):

Across the year, 2023 revenue has been very similar to 2022 revenue.

Fortunately the Treasury is very unlikely to be fooled by this clear obfuscation, as in their Alcohol Bulletin they state:

“the elevated receipts seen in July and August 2023 and decreased receipts seen in September and October 2023 may be indicative of traders forestalling clearances ahead of the change in tax regime that came into effect on 1 August 2023. As traders must pay duty the month after the accounting period when liabilities were accrued (which is usually the previous calendar month), most of August 2023 receipts would relate to July 2023 clearances which would fall under the old tax regime.”

Has the uprating fuelled inflation?

On 17 January 2024, most media outlets covered the unexpected rise in inflation (from 3.9% to 4%) and highlighted that this was largely attributed to increases in the cost of tobacco and alcohol. For instance, The Guardian stated:

“The increase in the annual rate was largely the result of increases in the cost of tobacco – after the chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, announced higher duty in the autumn statement – and alcohol.”

However, there are two important points to make:

- As the Office for National Statistics (ONS) explained, the increase was predominantly a result of the increase in tobacco duty. Alcohol and tobacco are categorised together, hence why media focused on both.

- Despite this rise – as health economist Colin Angus has shown – as of December 2023, beer, wines, and spirits were the only major food and drink categories to have become cheaper in real terms since the start of 2021.

The IMF and WHO

The International Monetary Fund published a briefing in early December on: ‘How To Design Excise Taxes on Alcoholic Beverages, which looked at the interplay between alcohol duties, revenue yield, and public health concerns.

In guidance on how countries should design excise duties on alcohol, the document states that although rates depend on local country context, they should be increased in most countries. They go on to state that a basic premise should be that duties cover the cost of alcohol harm:

“Although evaluating externalities and internalities is complex, countries can fall back on estimating the external economic costs associated with alcohol use to establish a reliable base for determining the optimal level of excise taxes. These costs include public health care expenses (related to the treatment of alcohol-related diseases) and those of criminal and less severe offenses, intended or otherwise, caused by alcohol consumption.”

Following suit a day later, the World Health Organization published a technical manual on alcohol tax policy and administration, and released data that showed how low the rate of taxes being applied to unhealthy products was across the world.

The findings highlight that the majority of countries are not using taxes to incentivise healthier behaviours. They particularly highlight that wine is exempt from excise taxes in at least 22 countries, most of which are in the European Region.

Scotland considers reintroducing Public Health Supplement – podcast feature

In the Scottish Government’s 2024-2025 Budget (published in December 2023), it states that:

“Recognising the importance of sustaining the public finances and public services, we are also committed to exploring the reintroduction of a non-domestic rates Public Health Supplement for large retailers in advance of the next Budget, while continuing work over the coming year to explore an Infrastructure Levy, to be implemented by spring 2026.”

The supplement was previously implemented between 2012 and 2015, and raised over £95 million for the government. The levy was paid by large retailers who sell both alcohol and tobacco. The media furore in 2011 and 2012 primarily focused on retailer opposition to the policy, with arguments that it was economically harmful, unfairly targeted big retailers, and that it wasn’t an evidence based public health policy. A 2016 analysis in the Milbank Quarterly explains how the levy was implemented and the issues with it.

With clear parallels to communications around the previous levy, the Daily Mail spotted the reference in the Budget 2024-25 and wrote that there were fears costs would be passed on to customers. The article quoted David Lonsdale, director of the Scottish Retail Consortium, who argued that:

“A surtax could also have consequences for the state of our high streets and town centres. Escalating rates bills could further undermine support at future ballots for business improvement districts (BIDs). It’s not difficult to see bumper increases in rates bills causing those affected to start voting consistently against BIDs, which are usually funded by a surcharge on the business rate. Finally, shop staff themselves may not be immune from the impact of any new surtax. That’s because staff bonuses at some retailers are dependent on the “profit and loss” performance of their own individual store.”

The Times followed up that ‘Health tax’ will punish shoppers, retailers claim’.

However, the measure is being supported by Scottish Labour, who spun it that private retailers were currently “cashing in on the SNP’s [minimum unit pricing] policy while rehabilitation services struggle to recover from being cut to the bone.”

Labour MSP Carol Mochan said:

“Minimum unit pricing is no silver bullet and without properly funded drug and alcohol partnerships then more lives will be avoidably lost. Scottish Labour is repeating its longstanding call for the implementation of a public health levy so that services and those who need them get the support that they need.”

Listen to our podcast to hear from Alcohol Focus Scotland’s Nicola Merrin, who explained the previous levy and what the charity would like to see with a future levy.

Controversial study on alcohol marketing restrictions concludes it isn’t a ‘Best Buy’

A study published in Addiction in early January reviewed evidence “for effects of total and partial bans of alcohol marketing on alcohol consumption”. The study found:

- Of the 11 studies identified, six studies reported null findings.

- Studies reporting lower alcohol consumption following marketing restrictions were of moderate, serious, and critical risk of bias.

- Two studies with low and moderate risk of bias found increasing alcohol consumption post marketing bans.

- The authors concluded that there was insufficient evidence to conclude that alcohol marketing bans reduce alcohol consumption.

The authors therefore stated that available evidence does not support the claim that banning alcohol marketing is a ‘Best Buy’ for reducing drinking.

The first point to make is that the findings are somewhat unsurprising, as very few countries have comprehensive alcohol marketing bans, so there is little evidence of their effect. However, the reason banning marketing is recommended is due to the causal role it has on alcohol consumption, particularly among children. The study authors do acknowledge this within their review, which partly highlights that the study abstract is not wholly representative of the detail within the review. The review outlines a number of limitations and caveats which are crucial to consider.

Firstly, they made it clear that the review did not mean that alcohol marketing restrictions do not work to reduce consumption, simply that they couldn’t find enough evidence to state that it does.

They also state that:

“It needs to be emphasized that the interventions studied were mostly enacted before the year 2000, many even before the year 1990—including two of three studies suggestive of desired effects. This is a key limitation because marketing bans enacted more than 30 years ago may have different effects today—in a market environment that is increasingly digital rather than physical.”

The authors reflect on how partial bans are unlikely to be effective, as the industry will always find a way to circumvent them, particularly as many bans have not included alcohol sponsorship.

They also discuss the evidence of marketing having a causal role in young people’s drinking and agree: “with the notation that the association between exposure to alcohol marketing and underage drinking is causal. However, this does not necessarily imply that a marketing ban results in an immediate reduction of alcohol use—as investigated in the studies included in this review.”

Their criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies within the review means that any studies which infer findings from, for example, tobacco marketing restrictions – which have largely positive public health findings with more robust methods and higher certainty of findings – have not been included.

Another important consideration relates to the morality of advertising a product that kills three million people across the world every year. Even if marketing bans did not lead to substantial reductions in consumption, should a multi-billion-pound industry be able to advertise a harmful drug to people without their consent or control? And as Alcohol Focus Scotland states:

“There is an inherent conflict between the commercial goals of businesses which sell unhealthy products such as alcohol, and the protection of the health of individuals and society. People have a need to be protected from the aggressive marketing of alcohol, but they also have rights under international law to be protected.”

Scottish Marketing Consultation

This review is particularly bad timing as the Scottish Government is currently considering the responses to their consultation on whether to restrict alcohol marketing. On 30 November 2023 they published an analysis of the responses.

Unsurprisingly, the majority of those with a link to the alcohol industry thought the proposals would not reduce alcohol consumption and harm, and were disproportionate to the scale of the problem.

There were very high levels of agreement among public health groups, the third sector, local government, and academic organisation.

The Scottish Government will be holding meetings with both public health stakeholders and the alcohol industry early this year to discuss ways of limiting young people’s exposure to alcohol promotions.

Following more targeted engagement with stakeholders, the plan is that a second consultation will ask for views on a narrower range of proposals.

Scotland’s First Minister, Humza Yousaf, has also backed Alcohol Focus Scotland’s campaign to reduce children’s exposure to alcohol advertising.

In a video for the charity, Yousaf acknowledged the high awareness children have of alcohol brands, and that evidence shows alcohol advertising leads to children drinking at an earlier age and for longer. He said that the government is “fully committed to improving public health and reducing the health risks faced by young people”.

Olympics signs up its first alcohol brand sponsor

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) has signed AB InBev as the first beer brand sponsor of the Olympics, and will run for the next three Summer and Winter Games.

Corona Cero, the zero alcohol version of Corona, will be the “global beer sponsor of the Olympic Games”.

The IOC’s own stated marketing mission is to “not accept commercial associations with products that may conflict with or be considered inappropriate to the mission of the IOC or to the spirit of Olympism”, so many will see this as a contradiction of that statement.

An industry analysis of AB InBev’s strategy to push its zero-alcohol product concludes that the main reason “has far more to do with hard-headed commercialism than anything else”. The writer argues that it makes sense to try to associate the zero-alcohol version with elite sports and that the steady rise in popularity for such products fits this strategy.

The advertising publication The Drum also highlights that the Olympics this year is being held in France, and their Loi Évin rules restrict alcohol advertising. This could mean that future Olympics may not see such restrictions.

1 million early deaths in England due to health inequalities

A review led by Professor Sir Michael Marmot has revealed that stark economic and health inequalities has resulted in one million premature deaths in England over the past decade.

It explains that a decade of poverty, austerity, and the COVID-19 pandemic are to blame.

Between 2011 and 2019, 1,062,334 people died prematurely in areas outside the wealthiest 10%, with an additional 151,615 premature deaths in 2020, partially due to the pandemic.

The report links 148,000 deaths directly to austerity measures implemented by the coalition government from 2010.

Marmot said:

“If you needed a case study example of what not to do to reduce health inequalities, the UK provides it. The only other developed country doing worse is the USA, where life expectancy is falling. Our country has become poor and unhealthy, where a few rich, healthy people live. People care about their health, but it is deteriorating, with their lives shortening, through no fault of their own. Political leaders can choose to prioritise everyone’s health, or not. Currently they are not.”

Wes Streeting, shadow health secretary, said:

“Where you are born, and the circumstances you are born into, shouldn’t decide how long you will live. It will be the mission of the next Labour government to both get our health service back on its feet and to build a fairer Britain where everyone lives well for longer.”

In an open letter in the BMJ, Sir Michael urged the next government to have health equity at the heart of its plans to avoid further loss of lives. He called for an independent health equity commissioner to be appointed, a new cabinet level health equity and wellbeing cross-department committee, and a national health inequalities strategy.

In related news, Guardian analysis of ONS data showed that life expectancy across the UK has fallen to its lowest level in a decade, mainly due to the pandemic.

Boys born between 2020 and 2022 can expect to live to 78.6 years, a decrease of 38 weeks compared with the same measure between 2017 and 2019. For girls, the expectancy for the same period was 82.6 years, having also fallen by 23 weeks compared with 2017 and 2019.

Pamela Cobb of the ONS said that although life expectancy figures had fallen, this did not necessarily mean that a baby born since the pandemic would live a shorter life, because of changing mortality rates during their lifetime.

Alcohol Toolkit Study: update

The monthly data collected is from English households and began in March 2014. Each month involves a new representative sample of approximately 1,700 adults aged 16 and over.

See more data on the project website here.

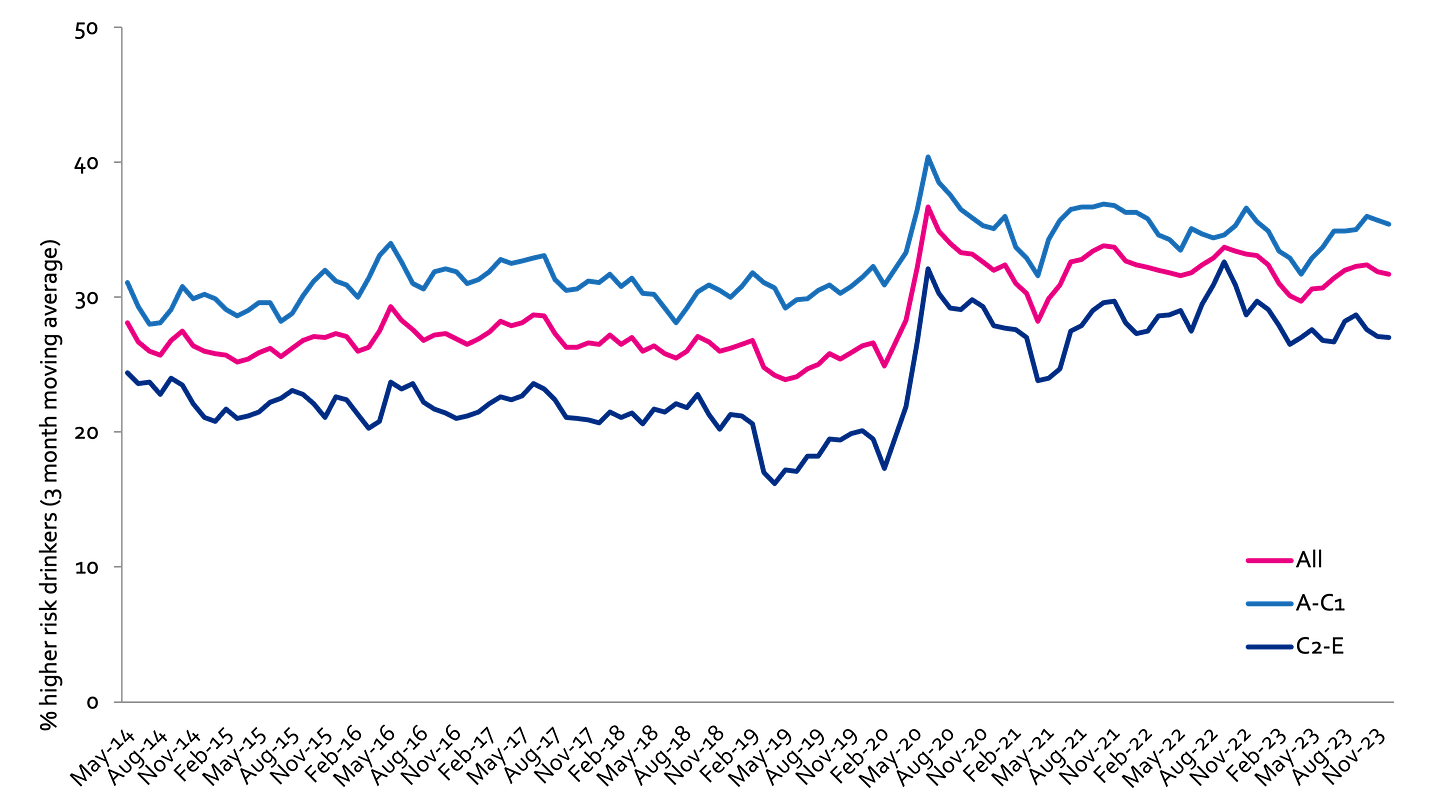

Prevalence of increasing and higher risk drinking (AUDIT-C)

Increasing and higher risk drinking defined as those scoring >4 AUDIT-C. A-C1: Professional to clerical occupation C2-E: Manual occupation

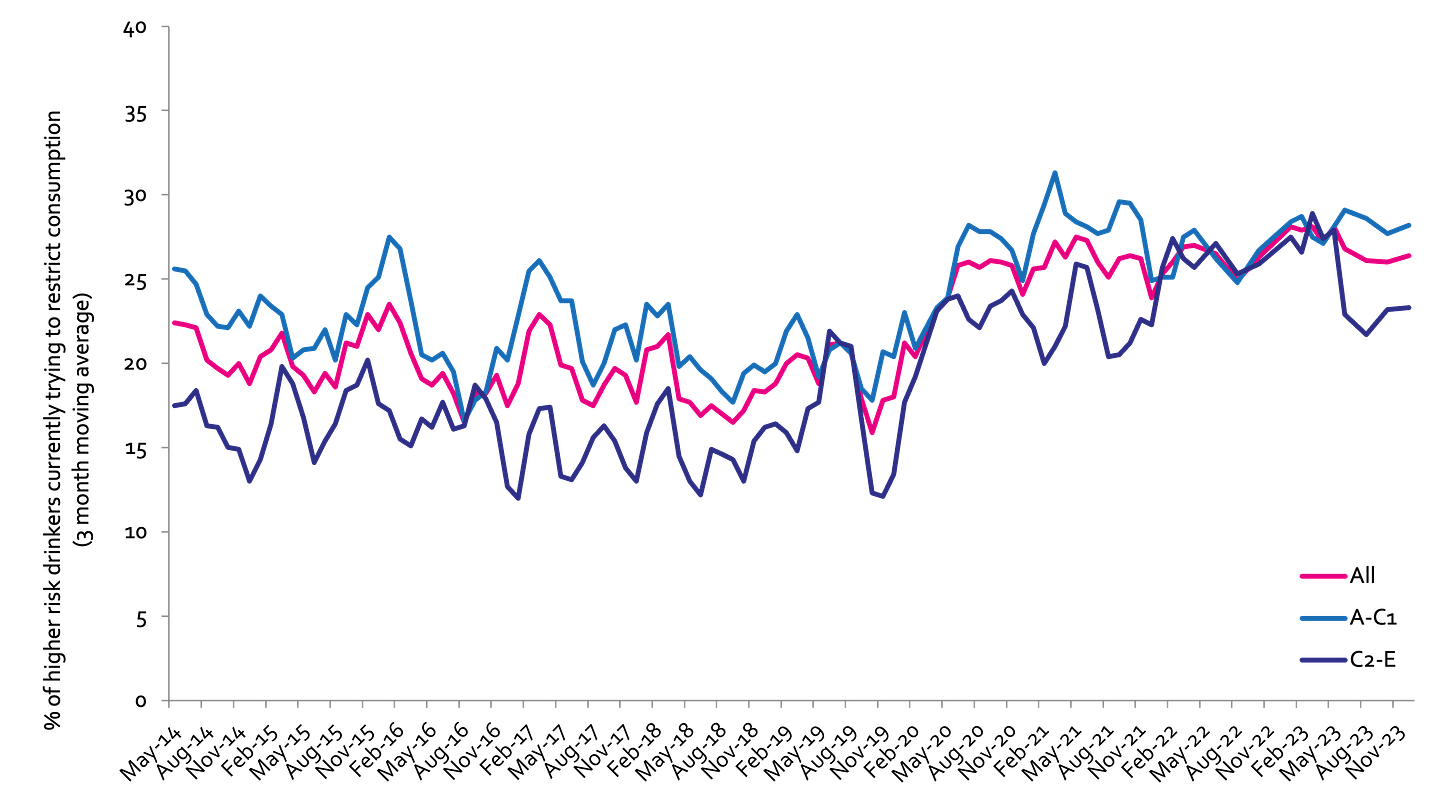

Currently trying to restrict consumption

A-C1: Professional to clerical occupation C2-E: Manual occupation; Question: Are you currently trying to restrict your alcohol consumption e.g. by drinking less, choosing lower strength alcohol or using smaller glasses? Are you currently trying to restrict your alcohol consumption e.g. by drinking less, choosing lower strength alcohol or using smaller glasses?

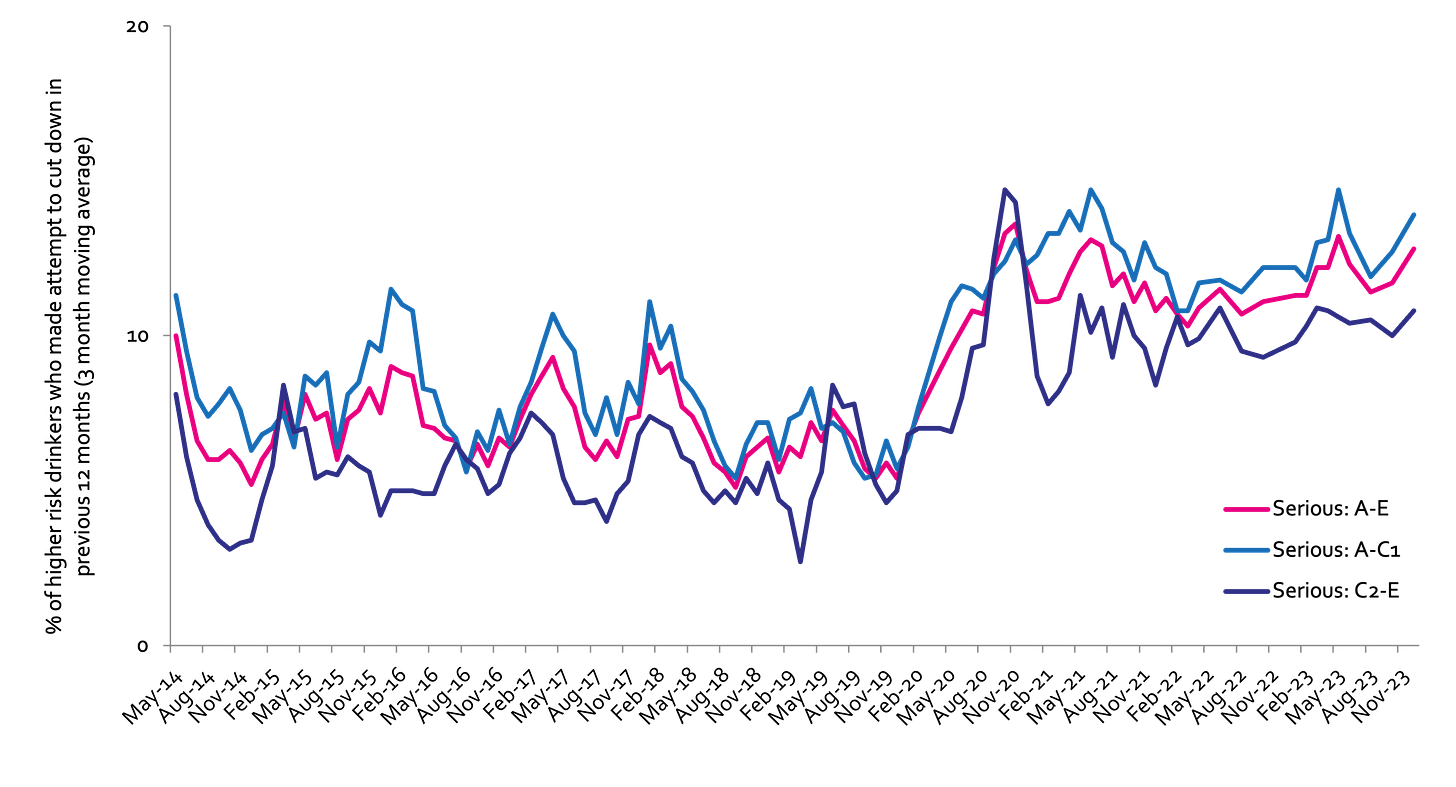

Serious past-year attempts to cut down or stop

Question 1: How many attempts to restrict your alcohol consumption have you made in the last 12 months (e.g. by drinking less, choosing lower strength alcohol or using smaller glasses)? Please include all attempts you have made in the last 12 months, whether or not they were successful, AND any attempt that you are currently making. Q2: During your most recent attempt to restrict your alcohol consumption, was it a serious attempt to cut down on your drinking permanently? A-C1: Professional to clerical occupation C2-E: Manual occupation

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

Gambling industry harms and parallels with the alcohol world

Will Prochaska –

Coalition to End Gambling Ads