In this month’s alert

Editorial – July 2021

Hello and welcome to the Alcohol Alert, brought to you by The Institute of Alcohol Studies.

In the July 2021 edition:

- Public Health England releases a report that shows the shocking death statistics from alcohol in 2020, particularly due to alcoholic liver disease

- Lancet study shows the huge number of cancer cases caused by alcohol across the world 🎵 Podcast feature 🎵

- An aspirational alcohol and cancer risk campaign launched in Australia 🎵 Podcast feature 🎵

- A study suggests early football matches lead to more drinking and subsequently more domestic violence

- The South African alcohol industry continues to battle the bans

- New handbook released refuting the 7 main industry arguments

We hope you enjoy our roundup of stories below. Thank you.

Subscribe to our podcast

Our podcast is now available on all major platforms including Apple, Spotify, and Stitcher. Subscribe now and don’t miss any future releases.

Consumption, hospital admissions and mortality: Public Health England report on alcohol during the pandemic

Public Health England (PHE) released a report entitled ‘Monitoring alcohol consumption and harm during the COVID-19 pandemic’ on 15 July, which highlights the increase in alcohol harm during 2020.

What it says about alcohol consumption

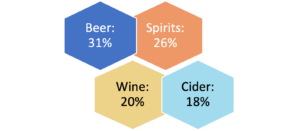

With a shift from on-trade alcohol sales to home drinking, off-trade sales increased by 25% from 2019. The largest increase was beer sales, at a 31% increase, however all types of alcohol sales rose:

Volume sales increase by alcohol type:

With the heaviest 20% of drinkers accounting for 42% of the increase in purchasing, the report states that “This may present a risk that alcohol harm persists or worsens among people already at risk of experiencing harm”.

PHE suggests that drinking patterns were polarised, with most people drinking the same as before the pandemic, and similar proportions of people drinking less and more.

How did this affect hospital admissions?

Admissions due to alcohol highlight the complexities around access to healthcare during the pandemic. Although unplanned admissions decreased by 3.2%, that does not suggest a reduction in harm. Instead, it is likely due to the ‘lockdown effect’ of people wanting to ease pressure on the NHS and also being fearful of catching COVID in hospital.

Whereas admissions due to alcohol-related mental and behavioural disorders fell, unplanned admissions for alcoholic liver disease increased by 13.5%.

The impact on mortality

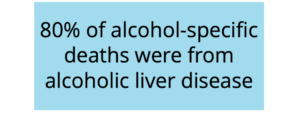

This increase in alcoholic liver disease admissions led to a dramatic 20% increase in alcohol-specific deaths, with 33% of deaths being among the most deprived societal group.

Despite hospital admissions for mental and behavioural disorders seeing a drop, there was a 10.8% increase in deaths from these disorders caused by alcohol. Alcohol poisoning deaths also saw an increase – of 15.4%.

Dr Katherine Severi, Chief Executive, Institute of Alcohol Studies, said:

“The evidence to support policy action is clear: tackling ultra-cheap alcohol through minimum unit pricing (MUP) and alcohol duty reforms will save lives and reduce costs for the NHS. Scotland has already witnessed a reduction in alcohol-specific deaths following the introduction of MUP in 2018, and with Wales adopting this measure it makes no sense for England to be left behind.”

“We also need to see better information provided to consumers about the health risks linked to alcohol, including the risk of breast and bowel cancer. The Chief Medical Officers’ low risk drinking guidelines must be present on all alcohol labels and adverts, to ensure the public are fully-equipped to make informed decisions about their drinking.”

The authors of the report concluded that:

“Tackling alcohol consumption and harm must be an essential part of the UK government’s COVID-19 recovery plan, given that tackling geographic health disparities are part of the government’s Build Back Better plans.”

741,300 cancer cases a year worldwide attributable to alcohol

🎵 Podcast feature 🎵

Researchers at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) (part of the World Health Organization), have found that over 740,000 cancer cases each year, or – 4.1% – are directly caused by alcohol consumption. In the UK this means 17,000 cases each year.

Alcohol causes cancer in a number of ways, including altering DNA, damaging carcinogen metabolites, and altering hormone regulators.

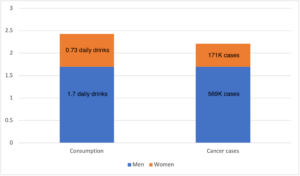

The study found that men accounted for 568,700 of the cases, or 77%. Most of the difference can be explain by different levels of consumption, with men globally consuming over double the amount of alcohol that women consume – 1.7 daily drinks compared to 0.73. Of course, this varies across world regions, as do the levels of consumption.

Comparison of men and women’s alcohol consumption and attributable cancer cases

However, the report highlights that with an increase in women involved in employment across the world, and therefore increased resources, women are consuming more alcohol. If this continues, we could see a shift in the proportion of cancer cases.

This is particularly poignant when you consider the alcohol industry’s targeting of women as a market for growth, especially in emerging markets such as India. Professor Jeff Collin discussed this at our sustainability seminar, which can you watch from here.

We spoke to lead author Harriet Rumgay on our podcast, who said:

“Alcohol industry lobbying parallels the tactics of the tobacco industry. It took so long for any kind of sanctions against the tobacco industry after we knew for decades about its links to harm. We need to make policymakers aware of how important it is for our environments to support healthy choices, and to not have such pressures from the industry.”

An important point that the report makes is that these cancer cases are not simply among those who drink heavy or risky amounts (>60g and 20-60g of ethanol a day respectively). Moderate drinking accounts for 14% of the cancer cases, showing that when it comes to cancer risk, there is no safe level of consumption.

The authors draw attention to WHO’s ‘best buys’ for tackling non-communicable diseases, including policies to increase taxation, limit availability, and reduce marketing of alcohol brands. Rumgay said that a top-down approach is required by governments to increase awareness regarding cancer risks and to reduce harm.

Dr Sadie Boniface, Head of Research at the Institute of Alcohol Studies, said:

“The results are in line with other studies, and scientists already knew that alcohol causes seven types of cancer. However there is low public awareness of this risk, particularly for breast cancer. The forthcoming consultation on alcohol labelling will be a real opportunity to introduce independent health information on alcohol products, so consumers can make fully informed decisions about their drinking.”

A top-down approach in Australia raises awareness of cancer risk: ‘Alcohol & Cancer Go Together’

🎵 Podcast feature 🎵

A health campaign that aims to educate the public about the risk of alcohol attributable cancer is expanding across Australia, with the Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education (FARE) leading the campaign. The stated focus is to “reduce alcohol use by increasing awareness of alcohol-caused cancer”.

In 2010 Western Australia launched an alcohol and cancer risk campaign called ‘Spread’, which received international recognition for its effects on behaviour change. An independent study of 83 English-language alcohol harm reduction ads found that ‘Spread’ was the most motivational at reducing alcohol consumption.

Following the success of Western Australia’s campaign, Victoria state launched its own version, and now Australian Capital Territory is following suit with the campaign ‘Alcohol & Cancer Go Together’.

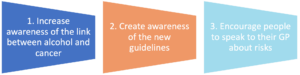

FARE is building upon the previous successful campaigns and incorporating the new alcohol guidelines, which suggest consuming no more than 10 standard drinks a week and no more than four standard drinks in one day.

The campaign will launch for an initial 10-week period across TV, social media, Spotify, YouTube, and outdoor media, to:

We spoke to FARE’s Chief Executive, Caterina Giorgi, who highlighted that the dominant messaging in Australia comes from the alcohol industry and has been particularly focused on drinking to cope with COVID. She argues that:

“These awareness campaigns that point to the risk and reasons why reducing drinking is so important, are vital to counter that excessive [alcohol] marketing that goes on.”

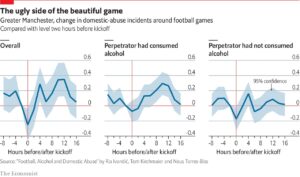

Earlier football matches lead to increased alcohol consumption and domestic violence incidents

A team at London School of Economics’ Centre for Economic Performance analysed police data to better understand how football matches affect domestic violence, and whether a change in violence is due to heightened emotional states or increased alcohol consumption.

They found that earlier football matches allow more drinking time and subsequently increase domestic violence. As the Guardian points out, “the findings raise questions about previous police requests to have some contentious games played earlier in the day”.

The data consisted of police calls and crime over an eight-year period in the Greater Manchester area and was compared to data on Manchester United and Manchester City football matches. This totalled almost 800 games.

The LSE team found that during the two-hour duration of the game, domestic violence incidents decreased by 5%, which they said suggests a “substituting effect of football and domestic violence”. However following the game, incidents increased by 2.8% each hour and peaked 10-12 hours later.

As there was no change in domestic violence relating to the outcome of the game (win or loss), and no change caused by sober perpetrators, the team concluded that the increase in violence is due to the increase in alcohol consumption.

There was no increase in violence when games kicked-off at 7pm, so the researchers say:

“Scheduling games later in the evening and implementing policies that reduce drinking can prevent a majority of the football related abuse from occurring.”

This study highlights the multitude of factors that need to be considered when implementing policies aimed at reducing violence. As study author Tom Kirchmaier said:

“what we actually substitute is a kind of visible crime for invisible crime. You have less crime around the stadium and so on, but you have issues more than eight hours later at home”.

There will undoubtedly be studies that look at the Euro 2020 Championship, alcohol consumption, and domestic violence. With the COVID-19 pandemic meaning matches were predominantly watched from home, it will be interesting to see how domestic violence incidents were affected.

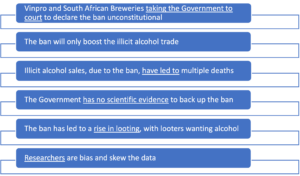

Alcohol industry in South Africa: an ongoing battle

At the end of June, South Africa implemented its fourth alcohol ban – which was then extended in mid-July – as the country continues to struggle to tackle coronavirus infections.

A few days later, the South African Medical Research Council released a study that found that full restrictions of alcohol reduced unnatural deaths by 26%, around 42 deaths a day. Where there was no full restriction, unnatural deaths were not significantly reduced.

The study did state that:

“while complete restrictions on sale of alcohol might avert unnatural deaths, long-term implementation of this policy would require significant trade-offs in terms of economic activity, as well as lives and livelihoods”.

Professor Charles Parry, co-author of the study, said the study adds to the body of evidence that shows policymakers should be adopting evidence-based strategies known to reduce alcohol harm:

“These include stricter advertising and promotions restrictions, minimum unit pricing, increased excise taxes, raising the minimum drinking age, and restrictions on container sizes among others.”

The alcohol industry was quick to hit back against the government ban, employing a number of known tactics aimed at undermining the scientific rationale and muddying the argument. These claims have been widely publicised, and touch on a point made by Aadilelah Maker Deidericks (Southern African Alcohol Policy Alliance, SAAPA) during the IAS sustainability seminar regarding the media exposure the industry gets compared to alcohol policy advocates – watch from here.

The South African industry tactics and arguments include:

The stated aim of the ban is to reduce hospital admissions due to alcohol-related trauma, in order to ease pressure on healthcare services and allow them to focus on tackling the pandemic.

The industry argued that the Government did not consult with them when deciding on the ban, and that their research was ignored. The judge who dismissed South African Breweries’ court claim said that in a state of disaster the government has the legislation to ban alcohol and that a lack of full and proper consultation is justified.

Arguments relating to looting and illicit sales are far more complex than simply due to the alcohol ban, and points at the disingenuous position the industry takes. For instance, since the imprisonment of ex-President Jacob Zuma, there has been widespread violence and rioting in the country after initial protests at his imprisonment turned into a wave of looting. The looting wasn’t directly due to the alcohol ban.

Maurice Smithers of SAAPA in late June argued that the main issue was of on-trade alcohol (pubs, bars, and restaurants) and not so much off-trade. He argued that people should be allowed to take alcohol home, as it is when people drink out that “the virus spreads, where people get involved in interpersonal violence and end up in hospital with alcohol-related trauma incidents”.

‘The Seven Key Messages of the Alcohol Industry’

A new publication looks at the strategies and arguments used by the alcohol industry to defend their products and prevent or delay effective harm reduction policies.

The book states that “certain projects and strategies look constructive, but are ultimately aimed at preventing or delaying government action”.

If you’d like a hard copy of the book, please follow this link.

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

Gambling industry harms and parallels with the alcohol world

Will Prochaska –

Coalition to End Gambling Ads