In this month’s alert

Editorial – June 2021

Hello and welcome to the Alcohol Alert, brought to you by The Institute of Alcohol Studies.

In the June 2021 edition:

- IAS seminar on Alcohol and the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals

- Extensive OECD publication details the investment case for alcohol control policies 🎵 Podcast feature 🎵

- New minimum unit pricing studies in Scotland bolster the argument for its implementation 🎵 Podcast feature 🎵

- Confusion over WHO global alcohol action plan 🎵 Podcast feature 🎵

- Brain imaging study suggests there is no safe level of alcohol consumption for brain health

- Study highlights the prevalence of alcohol advertising in the Rugby Six Nations

- Parliament debates labelling and the Misuse of Drugs Act

We hope you enjoy our roundup of stories below. Thank you.

Alcohol and the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals

IAS sustainability series, seminar 1

Seminar speakers:

- Chair: Kristina Sperkova,Movendi International

- Dudley Tarlton,United Nations Development Programme

- Professor Jeff Collin,University of Edinburgh

- Aadielah Maker Diedericks,South African Alcohol Policy Alliance

The Institute of Alcohol Studies hosted the first seminar in its four-part series on alcohol and sustainability, 10 June 2021. The seminar focused on the impact of alcohol on the United Nations’ (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the opportunities for improved alcohol policy arising from the Goals.

Goal 3.5 explicitly targets alcohol, with the commitment to ‘Strengthen the prevention of treatment of substance abuse, including…harmful use of alcohol’. Beyond that, alcohol has been identified as an obstacle to achieving 14 of the 17 SDGs, which can be seen as social, environmental, and economic.

Social goals such as ending poverty, hunger, achieving gender equality and maintaining peace and justice, are all affected by alcohol harm. Kristina Sperkova, President of Movendi International, highlighted that alcohol pushes people into poverty and keeps many there, and consumes spending that would otherwise be used on education and food. There are many studies that demonstrate the link between alcohol use and violence, particularly between young men and relating to domestic violence.

Ms Sperkova detailed the high environmental cost of alcohol production. Land required to grow crops for alcohol reduces biodiversity. Huge amounts of water are used for alcohol production, with 870 litres of water needed to produce one litre of wine. She pointed out that alcohol is often produced in places that have scarce water supplies, to serve the desires of higher income countries that have an abundance of water.

The economic burden of alcohol use across the world is enormous, with high-income countries seeing annual losses of between 1.4% and 1.7% of GDP due to alcohol harm. Much of this is due to the loss of productivity. In England in 2015, 167,000 working years were lost due to alcohol. It was suggested that more effective alcohol control policies would not only reduce the harm but would also help finance sustainable development.

The investment case

Dudley Tarlton, Programme Specialist at the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), introduced the work UNDP is doing in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO), to present the case for improving and implementing effective alcohol policies, with economic rationale being the main driver.

WHO’s SAFER initiative details the five most cost-effective interventions to reduce harm. Mr Tarlton stated that these five interventions would give a 5.8% return on investment.

Modelling by UNDP across 12 countries including Russia, Turkey, and Ethiopia, shows that investing in WHO’s recommended prevention measures would generate 19 billion USD over the next 15 years – mainly due to productivity gain – and 865,000 deaths would be averted.

UNDP is also looking into investment cases relating to alcohol-attributable deaths from causes such as liver cirrhosis, road injuries, tuberculosis, and HIV. They are drafting toolkits for countries to take up these policies and could be instrumental in getting revenue to help close covid-related fiscal gaps.

As lower socioeconomic groups would disproportionately benefit from the health benefits of increased alcohol taxes, Mr Tarlton highlighted that part of Goal 10 on reducing health inequalities would be targeted by such taxes.

The obstacle of the alcohol industry

Professor Jeff Collin, Edinburgh University, posited how the alcohol industry has positioned itself as aligned with the SDGs and as engines of development. The International Alliance for Responsible Drinking (IARD) has a toolkit for governments on how to build partnerships with the alcohol industry. Diageo’s ‘Business Avengers’ coalition highlights their role in aiming to achieve the SDGs. Namibian Breweries (NBL) has listed out which SDGs it is helping, including SDG 3: “NBL has a responsibility to minimise harmful alcohol consumption.”

Prof Collin explained that the industry is using the commitment of governments and organisations to SDG 17 – ‘Partnerships for the Goals’ – to push their own strategic agenda, particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Pre-pandemic, Diageo collaborated with CARE to address barriers to gender inclusion in the alcohol giant’s supply chain. Following the outbreak of the pandemic, Diageo supported CARE’s emergency response, giving clean water supplies, hygiene kits, and food.

According to Prof Collin’s work, the alcohol industry is using corporate social investment (CSI) and philanthropy to shape policy and pursue partnerships, to further its strategic interests. This is especially true in its targeting of women in developing countries, who are seen as a key emerging market. Pernod Ricard India launched an initiative around women entrepreneurs, which aptly shows the two faces of alcohol philanthropy, with the company’s CMO Kartik Mohindra stating:

“It is quintessential for brands to create products that appeal to them [women]. And if they don’t have more women in senior leadership roles, they are not likely to have the significant insights needed to tap into the highly sensitive minds of their ever-growing numbers of female consumers.”

In Southern Africa – as Aadielah Maker Diedericks of the Southern African Alcohol Policy Alliance (SAAPA) discussed – there are particularly striking examples of industry-government partnerships and conflicts of interest, with civil society in the region perceiving Big Alcohol’s involvement in the region as a form of neo-colonisation.

Ms Diedericks explained that policy makers are often on the boards of alcohol companies in the region, that governments hold shares in the industry, and the industry’s agenda is often successfully pushed through. Very few Southern African countries are taking on issues of marketing, pricing, and availability, instead focusing on road safety and underage drinking.

Both Prof Collin and Ms Diedericks said that SDG 17 has confused countries, with governments thinking the only relationship with the alcohol industry is one of partnership, ignoring potential conflicts of interest.

South Africa case study

South Africa has seen intense lobbying by the industry in recent months, with Ms Diedericks saying that they are using the narrative of job promotion to demonstrate their value. This is despite R246billion being spent on alcohol harm compared to R97billion in revenue.

The industry has campaigned extensively around the idea of economic loss associated with alcohol control policies, using dubious research to back up their claims. This comes at a time of high unemployment rate in South Africa and therefore gets a lot of media attention.

Ms Diedericks described the relationship between industry and South Africa’s government as “abusive” due to the industry threatening disinvestment in the country if there were controls to alcohol availability.

What next?

The speakers argued that the SDGs need to be used better as a rallying point for alcohol control measures. SDG 17 in particular should be used to develop policy coherence and that the building of coordinated approaches across other unhealthy commodities, such as junk food, should be considered.

There needs to be clear rationale for why enacting alcohol control policies would help achieve the SDGs, and taxation has a lot to offer towards sustainable financing.

Please watch the full seminar below, or click here for a 30minute edited version. Join us in September for seminar two in our four-part series.

New OECD report models economic effect of alcohol policies

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) published a book entitled ‘Preventing Harmful Alcohol Use’, 19 May 2021. It analyses the cost of alcohol consumption in 52 countries (OECD, EU and G20 countries), due to reduced life expectancy, increased healthcare costs, decreased productivity, and lower GDP. As with the IAS seminar on alcohol and sustainability, this report provides clear economic rationale for why countries should consider implementing alcohol control policies.

The report looks at trends and patterns in alcohol consumption in the 52 countries, as well as looking at the regional differences across Europe. The following statistics and modelling relate to the 52 countries, unless otherwise stated.

Health and economic burden of alcohol

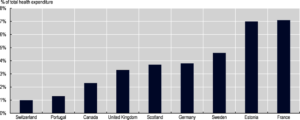

Health care costs for alcohol as percentage of total health care expenditure

Children’s education and bullying

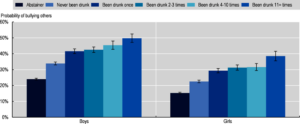

Probability of bullying others, children aged 11-15, with 95% confidence interval

Policies for reducing consumption

The report looked at which alcohol control policies countries currently implement and those that they should consider. It mentions the World Health Organization’s Global Strategy and Global Action Plan in reducing the harmful use of alcohol, referring to these as the best practice policy responses.

The report states that

“policies to reduce the harmful consumption of alcohol and associated harms cannot be addressed through one policy intervention – rather, a suite of interventions is needed within a comprehensive strategy”. This will “require a multi-sectoral approach, including health, law enforcement and social services sectors”.

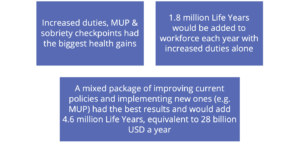

How would policies affect health and the economy?

Simulation modelling shows varying degrees of impact of alcohol control policies across the countries. Across the 48 countries analysed by OECD it was found that savings in healthcare costs are greater than the costs of running interventions.

How has minimum unit pricing affected Scotland and Wales so far?

Since Scotland implemented minimum unit pricing for alcohol (MUP) in May 2018 and Wales in March 2020, initial studies have shown a substantial shift in alcohol purchases and consumption.

On 28 May 2021, The Lancet published a study, by Professor Peter Anderson and colleagues, that analysed the purchasing habits of over 35,000 British households, in order to assess the impact of MUP in Scotland and Wales. Purchases in northern England were compared with Scottish purchases, and western England purchases with Wales. The measured changes associated with MUP were: price paid per gram of alcohol, grams of alcohol purchased, and amount of money spent on alcohol.

The results of the study were:

- In Scotland the price per gram saw a 7.6% increase and a purchase decrease of 7.7%

- In Wales the price increased by 8.2% and purchasing decreased by 8.6%

- The biggest changes were in households that generally bought the most alcohol. Little change was seen in households that bought small amounts of alcohol and those with low incomes

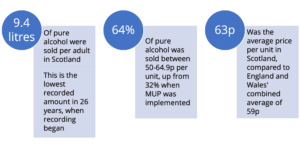

Following The Lancet report, on 17 June 2021 Public Health Scotland released its report Monitoring and Evaluating Scotland’s Alcohol Strategy. The report looked at alcohol purchasing, affordability and consumption in Scotland in 2020.

The report found that:

The report also shows a reduction in alcohol-specific deaths in Scotland from 2018-2019, with the rate for men being the lowest since 1996. However, rates are still higher in Scotland than in both England and Wales.

Alison Douglas of Alcohol Focus Scotland (AFS) said:

“We’re really pleased to see that as a nation we are drinking less for the third year running and that alcohol consumption is at a 25-year low – this is a good indication that minimum unit pricing is having the intended effect. But given nearly a quarter of Scots are still regularly drinking over the chief medical officers’ low-risk drinking guidelines, we can’t afford to take our eye off the ball where preventing alcohol harm is concerned.”

AFS has called on the government to raise the level at which MUP is set from 50p to 65p per unit, arguing that inflation has made it less effective since the legislation was passed eight years ago.

Following the success Scotland has seen, Baroness Finlay of Llandaff, Chair of the Alcohol Harm Commission, and Dr Katherine Severi, Chief executive of IAS, called on the UK Government to introduce MUP in England. They argued that there is now sufficient evidence of MUP’s effectiveness and that it is now more urgent than ever due to increases in high-risk drinking and alcohol-specific deaths in England.

Public Health Scotland released an interim report at the end of June, which suggests that there is little evidence that MUP has led to people substituting cheap alcohol with other substances or illicit alcohol.

Confusion over WHO’s global action plan on alcohol

In mid-June, the World Health Organization (WHO) published the first draft of its ‘Global alcohol action plan 2022-2030’.

The action plan’s aim is to aid in the implementation of WHO’s Global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol, which in turn aims to reduce morbidity and mortality due to harmful alcohol use and the ensuing social consequences. The strategy aims to “promote and support local, regional and global actions”, giving guidance and support on policy options, national circumstances, religious and cultural contexts, public health priorities, as well as resources and capabilities.

In response to the draft action plan, media across the UK focused on a statement included that said:

“Appropriate attention should be given to prevention of the initiation of drinking among children and adolescents, prevention of drinking among pregnant women and women of childbearing age.”

Most news reports lambasted the wording that women of childbearing age should be prevented from drinking.

Two prominent commentators quoted in press reports were Christopher Snowdon of the Institute of Economic Affairs, and Matt Lambert of the Portman Group, who said it was “unscientific, patronising and absurd” and “sexist and paternalistic” respectively.

Responding to the media furore, Professor Niamh Fitzgerald, University of Stirling, spoke on BBC Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour:

“It is striking that the commentators in the reports are from the alcohol industry. It is clearly an attempt to discredit WHO…before a WHO forum next week [week-commencing 21 June], which is looking at empowering governments against industry marketing. This is a first draft and that mention, which is ill-advised, doesn’t appear in the actions, so we shouldn’t worry that WHO is trying to stop women of childbearing age from drinking.”

Dr Sadie Boniface, the Institute of Alcohol Studies’ Head of Research, said “It is a shame that this one phrase in the report has hoovered up attention. This is the launch of an ambitious plan to address alcohol harm, and alcohol is the top risk factor globally for mortality among 15–49 year olds.”

According to the Sydney Morning Herald, Dag Rekve, Alcohol Policy Advisor at WHO, said

“It was just meant as the period where you are potentially carrying children and this is not generalising to all women in that age. It can be interpreted that we are saying that women of childbearing age should not drink alcohol and is a completely wrong interpretation and we will make sure that it’s not interpreted like that. If the media also can pick up on the incredible harm from alcohol in the world in the same way they picked up on this poorly formulated phrase, then perhaps we could really achieve something.”

No safe level of alcohol for brain health

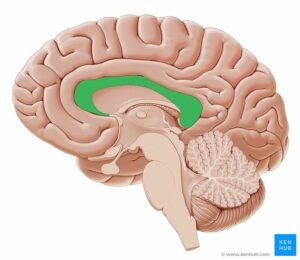

A yet to be peer-reviewed study suggests that all levels of drinking are associated with adverse effects on the brain.

Researchers at Oxford University, led by Dr Anya Topiwala, used brain imaging data from 25,000 participants of the UK Biobank study and looked at the relationship between this and moderate alcohol consumption.

The results found that higher consumption of alcohol was associated with lower grey matter density and that alcohol made a larger contribution than any other modifiable risk factor, including smoking. Negative associations were also found between alcohol and white matter integrity.

Particular damage was seen to the anterior corpus callosum, which connects the frontal lobes of the left and right hemispheres of the brain and ensures both sides of the brain can communicate with each other.

Dr Topiwala, said “There’s no threshold drinking for harm – any alcohol is worse. Pretty much the whole brain seems to be affected – not just specific areas, as previously thought.”

In response to the study, Dr Sadie Boniface, IAS Head of Research, said:

“While we can’t yet say for sure whether there is ‘no safe level’ of alcohol regarding brain health at the moment, it has been known for decades that heavy drinking is bad for brain health. We also shouldn’t forget alcohol affects all parts of the body and there are multiple health risks. For example, it is already known there is ‘no safe level’ of alcohol consumption for the seven types of cancer caused by alcohol, as identified by the UK Chief Medical Officers.”

The authors highlighted that one of the limitations of the study was the use of the Biobank data: that the sample is healthier, better educated, less deprived, and with less ethnic diversity than the general population. Dr Rebecca Dewey of the University of Nottingham responded to this, saying that “Therefore some caution is needed, but the extremely large sample size makes it pretty compelling”.

The study argues that current drinking guidelines could be amended to reflect the evidence about brain health rather than solely about cardiovascular disease and cancer risk. Professor Paul M. Matthews, Head of the Department of Brain Sciences, Imperial College London, supported this suggestion.

Alcohol, rugby and adolescent drinking

A study by Dr Alex Barker and colleagues that looked at the prevalence of Guinness advertising in the 2019 Rugby Six Nations Championship, found the following across the 15 games:

Two weeks after this study was published it was announced that the National Football League (NFL) in the US was to get its first spirits sponsor, with Diageo signing a multiyear deal. Until four years ago advertising of spirits was banned in the NFL, with beer advertising dominating.

Why is this important?

Dr Barker’s research states that exposure to alcohol advertising is associated with adolescent initiation of drinking and heavier drinking among existing young drinkers. It goes on to explain that the Advertising Standards Authority in the UK does not regulate footage of imagery from sporting events and although this should be covered by Ofcom it is not.

Sports sponsorship is self-regulated by the Portman Group, whose code states that it “seeks to ensure that alcohol is promoted in a socially responsible manner and only to those over 18” and that “drinks companies must use their reasonable endeavours to obtain data on the expected participants, audience or spectator profile to ensure that at least the aggregate of 75% are aged over 18”.

The study authors point out that even if 75% of the audience are adults, as sporting programmes are very popular with children they are still being exposed to regular alcohol advertising. If the remaining 25% are children, with huge sporting events there will still be millions of children seeing such advertising. The England versus Croatia Euros 2020 game had a UK audience of 11.6 million, which would potentially mean 2.9 million children seeing alcohol advertising during that game alone – a number acceptable under the self-regulatory rules.

The researchers argue that this weak regulatory approach should be reviewed and “Restrictions on, and enforcement of, alcohol advertising during sporting events are needed to protect children and adolescents from this avenue of alcohol advertising.” They go on to say that future studies should look at if this increased exposure leads to increased sales for alcohol brands.

The conversation around advertising of unhealthy commodities in sport has picked up in June, due to the actions of footballers at the European Football Championship.

Portugal’s Cristiano Ronaldo removed bottles of Coca-Cola from a press conference and held up a bottle of water declaring “Agua. Coca-Cola, ugh”. A few days later Paul Pogba removed a bottle of Heineken from his conference. This led to the launching of a Muslim athletes’ charter, which seeks to “challenge organisations” to make progress in supporting Muslim sportsmen and women. There are 10 points in the charter, such as “non-consumption of alcohol, including during celebrations, the provision of appropriate places to pray, halal food, and being allowed to fast in Ramadan”.

UEFA, the governing body of the Euros, then threatened to fine teams if players continued to snub sponsors. England’s manager Gareth Southgate came out in support of sponsors, saying “the impact of their money at all levels helps sport to function, particularly grassroots sport…we are mindful in our country of obesity and health but everything can be done in moderation”.

What happened in Parliament?

Obesity strategy

The House of Commons debated the implementation of the 2020 Obesity Strategy on 27 May. Minister Jo Churchill (Department of Health and Social Care) brought up the topic of alcohol labelling. She highlighted the number of calories some people in the UK consume via alcohol: “each year around 3.4 million adults consume an additional day’s worth of calories each week from alcohol”. She went on to state that the Government will be publishing a consultation shortly on the introduction of mandatory calorie labelling on pre-packed alcohol and alcohol sold in the on-trade sector.

Churchill said that the main aim was to ensure people were fully informed so that they can make educated choices on what they consume.

Labour MP Dan Carden’s contribution focused solely on alcohol labelling. He brought attention to the fact that non-alcoholic drinks have to display far more nutritional information than alcoholic drinks. He also pushed the UK government for a national alcohol strategy, as “We had the highest rate of deaths from alcohol on record this year. Alcohol-specific deaths are at an all-time high at a moment when drug and alcohol services are underfunded and mental health services are overstretched.”

During the debate, Alex Norris MP (Labour) and Jim Shannon MP (Democratic Unionist Party) agreed that there needs to be a stronger alcohol strategy.

Carden also spoke of the importance of bringing together strategies to combat obesity, drugs, gambling and alcohol.

Food and drink regulations

The House of Lords debated the Food and Drink Regulations 2021 on 19 May. Baroness Finlay of Llandaff discussed alcohol labelling, saying that people had the right to information in order to take control of their health and make informed choices. She argued that alcoholic drink labelling should form part of an obesity strategy and a comprehensive alcohol strategy.

“If the role of food labelling is to inform, to empower people to protect themselves from harm and to allow regulation to support that duty to protect our citizens from harm, updating the labelling becomes a moral imperative.”

Baroness Bennett of Manor Castle of the Green Party agreed with Baroness Finlay that alcohol labelling is currently inadequate.

Baroness Bloomfield of Hinton Waldrist (Conservative) responded to Baroness Finlay “The Department of Health is planning to issue a consultation on calorie labelling for alcohol in the near future with a view to making it a requirement from perhaps 2024.”

Misuse of Drugs Act

The Commons debated the 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act on 17 June. MPs agreed that the UK’s current drug policy is not working. Labour MP Jeff Smith argued that it should be liberalised to reduce harm, advocating the legalising of cannabis. He stated that alcohol is more harmful than many illegal drugs and yet it is legal.

“We mitigate the harm from alcohol use by legalising it, regulating it, making sure that it is not poisonous and making it safe, and we can invest the tax raised from its sale in the NHS and public messaging.”

Labour, Conservative and SNP MPs agreed with Smith, with Allan Dorans of the SNP saying that “Advice, support and education should be provided in the same way as they are for other health issues, including alcohol and tobacco.”

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

Gambling industry harms and parallels with the alcohol world

Will Prochaska –

Coalition to End Gambling Ads