In this month’s alert

Editorial – October 2014

Welcome to the October edition of Alcohol Alert, the Institute of Alcohol Studies newsletter, covering the latest updates on UK alcohol policy matters. In this issue, historian Dr Peter Catterall discusses the forgotten temperance roots of the Labour Party’s history in his essay “Labour and the politics of alcohol: The decline of a cause“, and solicitor Jonathan Goodliffe provides an analysis of the current legal challenge to minimum pricing in the European courts.

Other articles include: councils across the North East, the Association of Chief Police Officers, and the British Medical Association demanding urgent action on alcohol; industry figures declaring their support for Scottish minimum pricing in Brussels; a new map highlighting regional hotspots for alcohol-related liver disease; and research showing that one in six women drivers in Britain admit drink driving whilst over the limit.

Please click on the article titles to read them. We hope you enjoy this edition.

From opposing the drink traffic to 24 hour drinking: the Labour Party and alcohol

Historian charts the history of the Labour Party’s views on alcohol

With alcohol high on the political agenda and issues like minimum unit pricing being a matter of political dispute, in a new paper published by the Institute of Alcohol Studies, historian Peter Catterall charts the history of the Labour Party’s views on alcohol and asks how it was that a Party so heavily influenced by the non-conformist conscience and the temperance movement could end up introducing the 24-hour drinking Act

With alcohol high on the political agenda and issues like minimum unit pricing being a matter of political dispute, in a new paper published by the Institute of Alcohol Studies, historian Peter Catterall charts the history of the Labour Party’s views on alcohol and asks how it was that a Party so heavily influenced by the non-conformist conscience and the temperance movement could end up introducing the 24-hour drinking Act

He argues that the Act, based as it was on the delusion that liberalising the licensing law would reduce heavy public drinking and the attendant problems, was the logical outcome of a repudiation by the Labour Party in the 1930s of the temperance outlook of so many of its pioneers, in favour of the idea that the aim of policy was to promote moderate drinking rather than combat the drink culture and the drink trade.

Catterall explains that, while many Labour historians have written the alcohol question out of the Party’s history, it was, in fact, central to its origins and its early years. Keir Hardie, one of the founders of the Party, was a lifelong teetotaler and temperance man, as was Arthur Henderson, General Secretary of the Party from 1911–1932, during which time he played a key role in steering the new organisation into becoming a Party of Government. The majority of Edwardian Labour MPs were teetotal, and as late as 1935, 73 of the 154 Labour MPs returned in the general election were claimed to be abstainers. Combatting the alcohol question and the drink trade was held by many to be integral to building the new social order they aspired to create. A key text was ‘Socialism and the Drink Question’ by Philip Snowden, Labour’s first Chancellor of the Exchequer.

But there was never a single view: opinion was divided between prohibitionists and those who saw the answer in nationalization of the drink trade. There was also an anti-temperance lobby centered around working mens’ clubs, many of which depended on alcohol sales for their financial viability. During the interwar period, temperance came increasingly to be seen as a divisive issue within the Party and an electoral liability. The 1929 general election was the last in which the alcohol question was a significant issue. Thereafter, the prohibitionist cause became an embarrassment, and the policy of nationalization lost support, partly because it would have been expensive to implement. It was replaced by the policy of promoting moderate drinking through improved public houses. In the end, Labour’s only move in the direction of nationalization was the public control of licensed premises in the post-war New Towns under Attlee’s government in 1949.

By consciously dropping alcohol as an issue and freeing itself from the dominant influence of the chapel, Labour positioned itself for a straightforward fight with the Conservatives on economics rather than on an issue which had come to be seen as one primarily of personal morality. Temperance, like pacifism, became, in the course of the 1930s, a faith of individuals rather than the policy of a political party. And so the seeds were set for one of the most liberalizing reforms of the licensing law in British history.

‘Labour and the Politics of Alcohol: The Decline of a Cause‘ was written byDr Peter Catterall, University of Westminster and published by The Institute of Alcohol Studies. You can also listen to Dr Peter Catterall being interviewed on his paper by clicking on our Soundcloud link.

Photograph courtesy of Sylvia Scotting

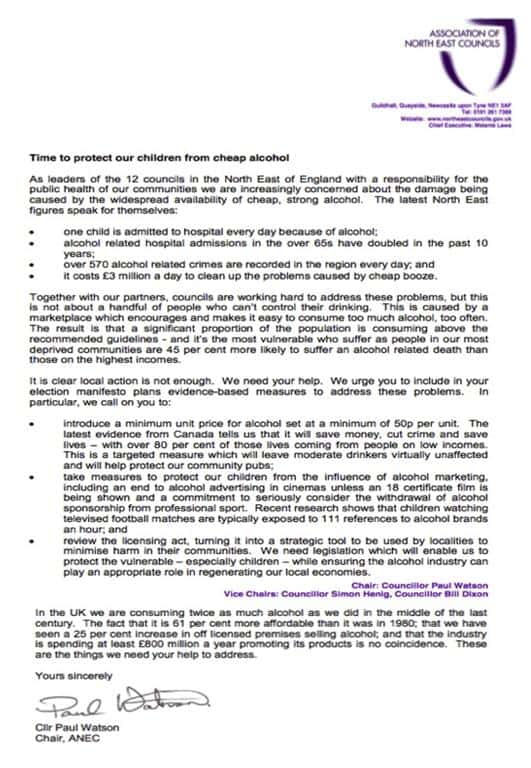

Council leaders call for urgent action on alcohol

The leaders of all 12 councils in the North East of England have issued an open letter to the Government calling for national measures to reduce the damage being caused in communities by the widespread availability of cheap, strong alcohol.

The Association of North East Councils (ANEC) has urged the three main political parties to include evidence-based measures in their election manifestos to address the problems continuing to be caused by alcohol.

The open letter coincided with the National Day of Action on Alcohol Harm on 5 September 2014, organised by a number of national partners including Balance, the North East Alcohol Office, to highlight the impact that alcohol is having on the region and to encourage MPs to support measures to reduce the levels of alcohol-related harm. This includes the introduction of a minimum unit price, making alcohol less available and restricting alcohol marketing.

Cllr Paul Watson, Chair of ANEC, said: “All 12 local authorities are working extremely hard with partners across the region to reduce the alcohol harms that we continue to see on a daily basis. However, this is not something that we can tackle at just a local level.

“We need support from Government to implement evidence-based measures to reduce the affordability, the availability and the marketing of alcohol and we urge the main parties to ensure that these are included in their upcoming manifestos. Only then will we truly be able to reduce alcohol harms.”

Colin Shevills, Director of Balance, added: “It’s extremely positive that 12 council leaders across the North East are calling on Government to prioritise tackling alcohol misuse – and also supporting the National Day of Action on Alcohol Harm.

“Here in the North East we continue to suffer at the hands of alcohol. The fact is that too many people are drinking too much too often and it is having a devastating impact across the region. This is driven by alcohol that is too cheap, too widely available and too heavily marketed.”

“No alcohol while pregnant”

Also in the North East, directors of public health advised the public that no alcohol is the safest option prior to and during pregnancy as they called for clearer guidelines for parents-to-be. The advice goes beyond that presently offered by national health authorities.

All 12 Directors of Public Health in the North East signed an open letter to support the no alcohol during pregnancy advice – and to call for consistent advice to be given by all healthcare providers from conception to birth.

The open letter was released to coincide with Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) Awareness Day, which took place on 9th September 2014. FASD is a series of preventable birth defects, both mental and physical, caused by drinking alcohol at any time during pregnancy.

The North East directors of public health say that around one baby is born with FASD each day in the region, and that FASD has a higher incidence rate than autism, Down’s syndrome, cerebral palsy, cystic fibrosis, spina bifida and sudden infant death syndrome combined.

Although it is still under-diagnosed, statistics show that approximately 1% of all babies born may have some form of FASD. This suggests that around 26,000 people in the North East could be affected by the disorder. On a national level it is thought that approximately 630,000 children and adults are affected.

Often the condition goes undiagnosed, or is misdiagnosed, for example as autism or ADHD, and this can lead to secondary disabilities.

Anna Lynch, Director of Public Health, County Durham and Chair of the region’s Directors of Public Health Network, said: “It is vital that parents-to-be are given consistent advice and guidelines around alcohol and pregnancy to ensure they can make informed choices.

“Conditions such as FASD are relatively unheard of which is why these awareness days are extremely important. These disorders last a lifetime and cannot be cured, yet are preventable.

“It’s important that we deliver one clear message that alcohol and pregnancy don’t mix and that no alcohol is the safest option prior to and during pregnancy.”

Mary Edwards, Programme Manager, Alcohol Treatment ,at Balance, said: “The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) advises women who are pregnant to avoid alcohol in the first three months in particular, because of the increased risk of miscarriage. However, researchers don’t know how much alcohol is safe to drink when pregnant. They do know that the risk of damage to your unborn baby increases the more you drink and that binge drinking is especially harmful. No alcohol is the best and safest choice.”

Dr Shonag Mackenzie, lead obstetrician at Northumbria Healthcare, said: “FASD is the most common preventable disability in children which is why we would advise people that no alcohol is by far the safest option before and during pregnancy. The condition is also under-diagnosed so it is potentially a much bigger problem than reported.

“However it’s important to highlight that if you’ve had a few drinks not to panic. In some instances people will have had a few alcoholic drinks without even knowing they are pregnant but it’s never too late to stop, and as soon as you do, you’ll stop the harm it could be causing. Alcohol affects the brain development so the sooner the better to avoid an increased risk.”

Long-term dangers of pre-natal bingeing highlighted

Further evidence of the harmful effects of binge drinking during pregnancy was provided by a study led by the University of Nottingham, though the conclusions of the authors arguably did little to clear up the confusion regarding the appropriate message to pregnant women.

The study suggests that binge drinking during pregnancy can increase the risk of mental health problems in 11 year-old children, particularly hyperactivity and inattention, and can have a negative effect on their school examination results.

The study found this was the case even after a number of other lifestyle and social factors were taken into account. These included the mother’s own mental health, whether she smoked tobacco, used cannabis or other drugs during the pregnancy, her age, her education, and how many other children she had.

The research examined data from more than 4,000 participants in the ‘Children of the 90s’ study, and the work builds on earlier research on the same children that found a link between binge drinking in pregnancy and their mental health when aged four and seven, suggesting that problems can persist as a child gets older. Other effects, such as on academic performance, may only become apparent later in a child’s life.

Binge drinking was defined as drinking four or more units of alcohol in a day on at least one occasion during the pregnancy. The women were asked about their drinking pattern at both 18 and 32 weeks of pregnancy and again when their child was aged five. At age 11, parents and teachers completed questionnaires (on more than 4,000 participants) about the children’s mental health. Information about academic performance (on almost 7,000 participants) was based on the results of the Key Stage 2 examinations taken in the final year at primary school. These exams assess a child’s ability in English, mathematics and science.

One in four mothers reported a pattern of binge drinking at least once during pregnancy and more than half of these said they had done so once or twice in the month prior to being asked. The majority who reported binge drinking when asked at 18 weeks, also reported this when asked again at 32 weeks, suggesting that the pattern might have persisted during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy although this cannot be known for sure.

To assess the impact of episodic binge pattern drinking in women who did not drink regularly during pregnancy, the analysis separated out binge pattern and regular daily drinking. After disentangling binge pattern and daily drinking in this way, episodic binge pattern drinking was associated with slightly higher levels of hyperactivity and inattention according to the teacher and with lower academic scores. On average, scores were about 1 point lower in the Key Stage 2 examinations, even after other key factors including both parents’ education had been taken into account.

Risks even with ‘occasional’ binge drinking

According to the parent questionnaires, binge pattern drinking was also associated with slightly higher levels of hyperactivity and inattention. This effect was more pronounced in girls than boys, possibly reflecting the choice of questionnaire used for the study, with any possible effects being more readily demonstrable in girls as hyperactivity and inattention behaviours tend to be more common in boys.

Binge pattern drinking when the child was aged five was not associated with negative effects on mental health and school results at age 11, suggesting that the risks of alcohol exposure occur while the child is in the womb.

Professor Kapil Sayal from The University of Nottingham, the report’s main author, said: “Women who are pregnant or who are planning to become pregnant should be aware of the possible risks associated with episodes of heavier drinking during pregnancy, even if this only occurs on an occasional basis.

“The consumption of four or more drinks in a day may increase the risk for hyperactivity and inattention problems and lower academic attainment even if daily average levels of alcohol consumption during pregnancy are low.

“The study’s findings highlight the need for clear policy messages about patterns of alcohol consumption during pregnancy, whereby women who choose to drink occasionally should avoid having several drinks in a day. The information was collected in 1991-1992 when attitudes towards drinking in pregnancy may have been different in the UK. As this was over 20 years ago, this may not necessarily reflect the current picture.”

The research is published in the journal European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

ACPO demands more action to tackle drunkenness

Police forces use weekend in September to encourage drinkers to take responsibility for themselves on nights out

The Association of Chief Police Officers has called for greater control of the alcohol industry to tackle the problems of drunkenness. The call came as the police launched a national campaign over a weekend to highlight the alcohol issue. However, sections of the alcohol trade described the call as misleading and unhelpful.

The Association of Chief Police Officers has called for greater control of the alcohol industry to tackle the problems of drunkenness. The call came as the police launched a national campaign over a weekend to highlight the alcohol issue. However, sections of the alcohol trade described the call as misleading and unhelpful.

In 2013, police chiefs highlighted the drain on police resources caused by excessive drinking and called for alternatives, such as ‘drunk tanks’, to put the cost back to the drinkers. However, they are unhappy that, despite a big debate, there have been few changes and police still have to pull officers off their beats to deal with the drunk and disorderly in town centres at the weekend.

Over the weekend of September 19, police forces tried to highlight the problem and encouraged drinkers to take responsibility for themselves on a night out.

Police were out on the streets at violence ‘hot spots’, where they tackled binge drinking by issuing warnings to those heavily under the influence of alcohol, with some being asked to leave the town or city centres.

During the period, officers visited schools to speak to pupils about alcohol awareness, as well as universities where police targeted the thousands of new students taking part in fresher’s week celebrations.

Police in Suffolk highlighted the vulnerable position intoxicated drinkers leave themselves in by visiting people with a health professional in the days following a heavy drinking session and showing them footage of their behaviour caught on body-worn video.

In some venues breathalyser trials were set up, offering customers a chance to test their intoxication levels. In Loughborough, a number of venues trialled a scheme whereby people were breathalysed as a condition of entry. There were also roadshow events to promote responsible drinking, and street pastors were on hand in town centres to offer advice and support. Forces also tweeted about the alcohol-related issues they dealt with.

National Policing Lead on Alcohol Harm, Chief Constable Adrian Lee, who is also Chief Constable of Northamptonshire Police, said that progress had been limited over the last 12 months and that there was a real need for more to be done.

He said: “We raised this issue last year and got real support from the public, other emergency services, health services, some parts of the alcohol industry and politicians. We have seen increased efforts in the last 12 months from the alcohol industry and licensed venues to tackle excessive drinking, but these efforts have barely scratched the surface of a problem that is blighting our communities.

“Voluntary measures such as stopping the production of ‘super strength’ products in large cans, a commitment to responsible promotion of alcohol in shops and supermarkets and a small investment in education in schools are steps in the right direction. But they are small steps. There is much more to be done.”

CC Lee measured the impact of alcohol in his force and found that in a 24 hour snapshot 27% of incidents reported to Northamptonshire Police were alcohol-related; this doesn’t include the demand on the police from weekend drinkers.

CC Lee said “To make real change we need strong oversight of the alcohol industry, we need to look at ways of dealing with the price and availability of alcohol and effective treatment for offenders with alcohol problems. But there is only so much progress we can make without individuals taking personal responsibility for their drinking. Social tolerance for excessive drinking is far too great and it is considered normal to be so drunk that people are not in control of themselves. This puts an enormous burden on police and health services and affects the service we offer to the public.”

Trade reaction

Responding to senior police describing the UK’s drinking culture as “out-of-control”, the Association of Licensed Multiple Retailers, representing the independent pub sector, argued that pubs and clubs in the UK were contributing to positive changes in attitudes towards alcohol consumption and called for this work to be acknowledged.

The ALMR has also warned that ‘heavy-handed blanket measures’ may have the unintended effect of creating or displacing problems. ALMR Chief Executive, Kate Nicholls said: “The language being used …. certainly makes for daunting reading, but the truth is nowhere near as desperate. By every measure, sales and consumption of alcohol are down dramatically as are incidents of disorder.

“Over seventy per cent of all alcohol sold in the UK is for consumption in the home and total alcohol consumption is at its lowest for a century. Additionally, instances of alcohol-related violent crime have declined 32% since 2004. To suggest that our towns and city centres have become unmanageable no-go zones is misleading and unhelpful.

Kate Nicholls continued: “Pubs and clubs across the UK are investing time, energy and money in promoting best practice and partnership schemes such as Best Bar None and they are working. Earlier this year a National Pubwatch report stated that 79% of police believed Pubwatch schemes had contributed to declining levels of crime. If a problem arises in a certain area, we want to work with local authorities and local police forces to address those issues; clumsy responses such as a blanket introduction of mandatory breath tests and a roll-out of drunk tanks may not have the intended effect and could simply increase consumption and problems in a domestic setting.

“Our staff members behind the bars and on the doors already do a fantastic job managing customers and there is a risk that heavy-handed measures may only displace the problem. Antagonising large queues and groups of people will likely increase the risk for frontline staff already in harm’s way. We also need to be careful that we do not push any problems into the home, away from where we can deal with them.”

BMA Manifesto calls for action on alcohol

With the UK general election coming into view, the British Medical Association (BMA) has set out its vision for doctors, patients and the health service in a four-step manifesto for the health of the nation, with action on alcohol among its key priorities

The manifesto Four Steps for a Healthier Nation calls for a commitment to introducing a minimum unit price for alcohol of no less than 50 pence, along with general efforts to restrict or limit the promotion and availability of alcoholic drinks.

To promote public health, the manifesto also urges politicians to maintain the UK’s tough stance on tobacco, by encouraging policy makers to adopt the highly controversial BMA proposal to ban the sale of cigarettes to those born after the year 2000, and it seeks a commitment to curbing the availability of unhealthy foods, and providing greater access to sport and exercise.

In addition to promoting public health, the other three steps to health are:

- working in partnership with doctors to ensure a sustainable NHS

- supporting the medical workforce, and

- assuring the quality and safety of patient care

Minimum alcohol pricing would be up to 50 times more effective than below cost selling ban

And the greatest effects would be in harmful drinkers, say experts

Introducing minimum unit pricing in England would be up to 50 times more effective than the Government’s recent policy of a ban on below cost selling as a way of tackling problems caused by cheap alcohol, finds a study published on bmj.com.

Increasing the price of alcohol has been shown to be effective in reducing both consumption levels and harms, and the UK Government has been considering different policy options for price regulation in England and Wales.

In 2010, the Government announced a ban on “below cost selling” to target drinks which are currently sold so cheaply that their price is below the cost of the tax (duty and VAT) payable on the product. Plans to introduce a minimum unit price for alcohol of between 40p and 50p per unit were shelved in 2013.

So researchers at the University of Sheffield decided to compare the effects on public health in England of these two alcohol policies.Using a mathematical model alongside General Lifestyle Survey data, they estimated changes in alcohol consumption, spending, and related health harms among adults for 2014-15.The population was split into subgroups of moderate, hazardous, and harmful drinkers, according to weekly consumption guidelines.

The team estimates that below cost selling will increase the price of just 0.7% of alcohol units sold in England, whereas a minimum unit pricing of 45p would increase the price of 23.2% of units sold.

Below cost selling will reduce harmful drinkers’ mean annual consumption by just 0.08%, around three units per year, compared with 3.7% or 137 units per year for a 45p minimum unit price (an approximately 45 times greater effect).

The ban on below cost selling has a small effect on population health, they add – saving an estimated 14 deaths and 500 admissions to hospital per year. In contrast, a 45p minimum unit price is estimated to save 624 deaths and 23,700 hospital admissions.

Furthermore, most of the harm reductions (for example, 89% of estimated deaths saved per year) are likely to occur in the 5.3% of people who are harmful drinkers because they buy the greatest share of cheap alcohol.

Additional analyses suggest that the relative scale of impact between a ban on below cost selling and a minimum unit price “are robust to a variety of assumptions and uncertainties,” say the authors.

Despite some study limitations, the authors say they found “very small estimated effects for banning below cost selling” and showed, in comparison, “that a minimum unit price of 45p would be expected to have 40-50 times larger reductions in consumption and health harms.”

In an accompanying editorial, Tim Stockwell from the Centre for Addictions Research at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada, says minimum pricing in Canada “has been associated with significant reductions in alcohol related harm.” Furthermore, Canadian research suggests that the estimated benefits of minimum unit pricing in the Sheffield model are “highly conservative.”

Unlike Canada, he wonders why there has been such industry opposition to minimum unit pricing in Europe. “Could it be that minimum unit pricing in the EU would set some dangerous precedents for commercial vested interests?” he asks.

Either way, the outcome of a case pending at the European court of justice will have major implications for the future of public health in Europe, he concludes.

Please follow the link to the editorial ‘Minimum unit pricing for alcohol’ which accompanies the study published in the BMJ on 30 September 2014.

The study ‘Potential benefits of minimum unit pricing for alcohol versus a ban on below cost selling in England 2014’ is available to view here: http://www.bmj.com/cgi/doi/10.1136/bmj.g5452

Industry support for MUP in Scotland

Though the Scottish government initiative to put a minimum unit price (MUP) on alcohol has been challenged by the Scotch Whisky Association and other

industry bodies, other members of Scotland’s alcohol industry have come out in

support of MUP

Speaking in Brussels at a conference on MUP, organised by the European Public Health Alliance (EPHA), Paul Bartlett, Group Marketing Director at C&C (the producers of Tennent’s Lager) said that it was essential that drinks companies took a step forward to reduce the harm from alcohol.

Speaking in Brussels at a conference on MUP, organised by the European Public Health Alliance (EPHA), Paul Bartlett, Group Marketing Director at C&C (the producers of Tennent’s Lager) said that it was essential that drinks companies took a step forward to reduce the harm from alcohol.

“It’s not acceptable what is happening in the market at the moment.” Mr Bartlett said.“In Scotland, it’s clear that we have a unique relationship with alcohol. It is a problem. It’s not affecting all people, but there is a significant minority who do need to be thought carefully about.”

Paul Watson, CEO at the Scottish Licensed Trade Association, stated that his association has argued for alcohol price control since this was abolished in the 1960s, because, he said, “there have been unscrupulous bar operators, cutting alcohol prices, or running irresponsible drinks operations.”

Mr Watson continued: “We have repeated that cutting alcohol prices to boost sales would have a detrimental effect on our reputation and development of our trade and we have significantly increased alcohol problems in our country. Minimum pricing is a crucial piece of legislation which can help us to continue to improve our trade and continue to provide quality premises at the centre of the sale.

Speaking for Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems (SHAAP), Professor Peter Rice said that tackling price was the most effective and cost-effective way of tackling the issue, and he argued that the introduction of MUP would result in Scotland emulating France, where, he said, consumers decided to buy more expensive wine as they became more educated on health. But while consumers started drinking less wine, they spent the same amount of money as they chose quality.

Donald Henderson, Head of Public Health in the Scottish Government said ministers in the Scottish Government found these arguments very persuasive. He said that harm from alcohol was concentrated in lower-income groups and MUP was an instrument that would solve many of the health problems Scotland was facing.

The Scottish legislation was passed without opposition in May 2012. The Minimum Unit Price (MUP) was set at 50p per unit. The legislation should have been implemented in April 2013.

However, it was delayed by a legal challenge by trade bodies representing international alcohol producers – the Scotch Whisky Association (SWA), the European Spirits Association (Spirits Europe) and Comité Européen des Enterprises Vins (CEEV).

The case has now been referred to the European Court of Justice. MUP will not come into force until the legal process is complete. In considering its position, the ECJ will ask for written submissions from EU member states, and parties directly involved in the court case. The deadline for submissions to the court is 21st October 2014.

Applying a minimum price to alcohol

By Jonathan Goodliffe, solicitor, England and Wales

Introduction

The Court of Justice of the European Union (which sits in Luxembourg) is due to rule on a series of legal questions relating to the sale of alcoholic drinks. The answers to these questions are expected to determine whether applying a minimum price to alcohol is or is not a practicable policy within Europe.

The Court of Justice of the European Union (which sits in Luxembourg) is due to rule on a series of legal questions relating to the sale of alcoholic drinks. The answers to these questions are expected to determine whether applying a minimum price to alcohol is or is not a practicable policy within Europe.

Background

In 2012 the Scottish Parliament passed the Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) Act. The purpose was to apply a minimum unit price to alcohol. Scientific evidence suggests that this is an effective harm reduction strategy. It has been demonstrated significantly to reduce consumption levels. It is well within the domestic competence of member states under European law. However, the initiative is opposed by some powerful industry interests.

The case against minimum pricing

The argument is that the Scottish government’s proposals had effect as a “quantitative restriction on imports”. This is because they would have more impact on importers of alcoholic drink than on domestic producers. Such restrictions are banned under article 34 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

Article 36 adds that article 34 does not preclude restrictions “justified on grounds of … the protection of health and life of humans”. However, before the Treaties had acquired their modern form, the European Court had applied a gloss to this provision. The Court ruled that restrictions should not be applied under article 36 more than is “necessary” to protect the interest in question.

Those who oppose minimum pricing argue that “the increase of excise duty appears to be a better option to reach the goals sought”. This is because it will not distort trade in the same way as minimum pricing. Accordingly minimum pricing is said to be not justified.

The legal challenge

Industry interests brought judicial review proceedings to challenge the Act. The first instance proceedings were in the Outer House of the Scottish Court of Session. The judge, Lord Doherty, dismissed the proceedings. He considered that the Scottish government’s case under article 36 had been made out. He came to this conclusion by applying existing principles of European law, rather than reinterpreting or extending them. So he did not think that a reference to the European Court for a ruling on the legal issues was necessary.

The Appeal

On appeal, however, Lords Eassie, Menzies and Brodie in the Inner House of the Court of Session took a different view. They considered that the European Court should be asked to give a ruling. The industry case was supported by someother European countries, particularly those which are major wine producers.

The reference to the European Court

The European Court will therefore rule on the legal issues. This process will probably take up to two years. When all the arguments have been made and discussed, an advocate general at the Court will give a detailed opinion as to what ruling he/she considers the Court should make. The Court will make its ruling 6 months to a year later. It usually, but not invariably, follows the views of the advocate general. There is no right of further appeal in the CJEU, although further proceedings in the Scots courts may be necessary to apply or interpret the European Court’s judgment.

The questions put to the European Court

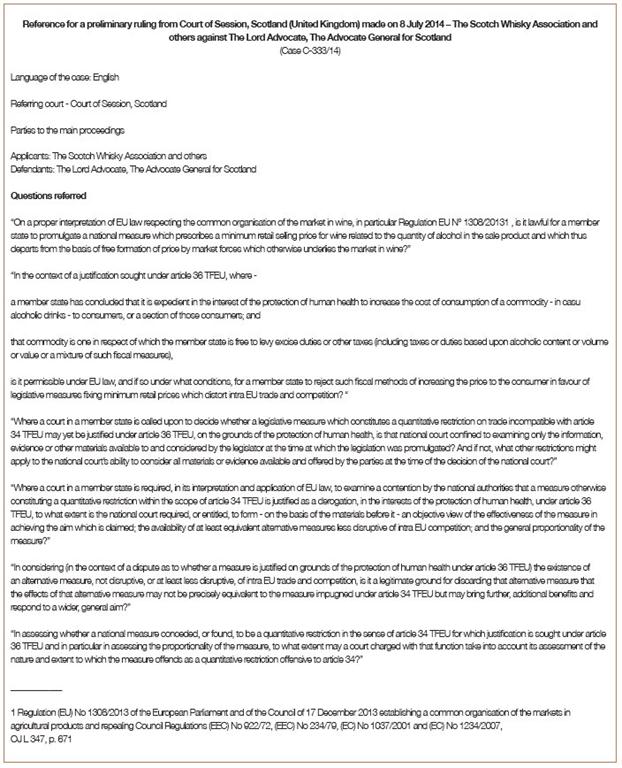

I summarise these detailed questions (see text box opposite). I paraphrase the convoluted language in the official version:

Is minimum pricing consistent with detailed EU regulations on the common organisation of the market in wine? These regulations cover everything one could possibly imagine about wine apart from minimum pricing. The implication here is that if minimum pricing was compatible with EU law one would expect it to be expressly provided for.

Given that member states are able to influence the price of alcoholic drink through fiscal measures, to what extent is it open to them to reject such measures in favour of minimum pricing?

Suppose a national court has to consider a quantitative restriction on trade imposed by a statute like the Minimum Pricing Act. It has to rule on whether it is justified under article 36. In that event must the court just consider the information, evidence and other materials considered by the legislator when passing the statute. Or can it go beyond this, and if so, how far?

Suppose a national court has to consider whether a quantitative restriction on trade (such as that imposed by the Minimum Pricing Act) is justified under article 36. Can or should the court consider whether the restriction is actually effective in achieving its aim? Also are equivalent measures less disruptive to competition available? And are the original restrictions “proportional”, or are they a “sledgehammer to crack a nut”.

Suppose the Court is considering an article 36 justification for a quantitative restriction. Should it reject equivalent measures and uphold the restriction under challenge where the alternative measures do not achieve precisely the same effect as the restriction? Should this course also be adopted even when the alternative measures are said to “bring additional benefits and respond to a wider general aim”.

Suppose a Court is determining whether a quantitative restriction is justified under article 36. Is it entitled to take into account the nature and extent to which the measure “offends as a quantitative restriction offensive to article 34”? The point being made here seems to be that some breaches of article 34 may be so “offensive” that their offensiveness should be taken into account in deciding whether they are justified. An analogy might be the case of a schoolboy’s punishment being increased where his behaviour is particularly brazen.

Is competition more important than health?

The impression that arises from these questions is that the supporters of minimum pricing are on the defensive, despite winning the Scots proceedings at first instance. The questions explore what the Inner House judges clearly consider to be weaknesses in the Scottish government’s case. The starting point of the industry interests and the countries that support them, is that competition is more important within the European Union than health and welfare. This may have been the case with the original Common Market, founded in 1957. However since then the treaties have been recast. As they currently stand:

article 3 of the Treaty on European Union (“TEU”) states that “the Union’s aim is to promote peace, its values and the well-being of its peoples.”

article 6 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”) indicates that one of the functions of the Union is to support “the protection and improvement of public health”.

article 9 of the TFEU states that the Union “shall take into account requirements linked to the promotion of … human health”.

article 24 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights says that “Children shall have the right to such protection and care as is necessary for their well-being” [including protection from harm caused to them by the drinking of adults].

article 35 of the Charter says “A high level of human health protection shall be ensured in the definition and implementation of all the Union’s policies and activities.”

I have prepared a 5 page analysis of these provisions and others [link].

Promotion of competition, on the other hand, is not identified as an objective of the Union as such, as opposed to a means to achieve the defined objectives.

It follows that the old case law of the Court on the interpretation of articles 34 and 36 and the Commission’s approach to it should be reconsidered. For example quantitative restrictions on imports of alcohol applied under article 36 (e.g. the Minimum Pricing Act) should no longer need to be “necessary” to protect the interest in question. Applying such a standard imposes too much of a burden on a country like Scotland, which is taking serious measures to reduce alcohol related harm and is being prevented from bringing into force a statute passed by its democratically elected Parliament.

The emphasis in competition policy should not be not on eliminating alcohol harm reduction measures because they interfere with competition. Any really effective measures are bound to have that result. In the 1950s and 1960s the European alcohol market was anti-competitive. The Commission got rid of that problem at the cost of increasing consumption and harm.

So the improvements achieved in the market for alcohol over the last 50 years should now be balanced by measures aimed at reducing the harm arising from the Commission’s own success. The Commission and the industry should learn to live with anti-competitive practices when they serve one or more of the higher aims of the European Union.

Chief Medical Officers report focuses on mental health and addictions

More screenings, brief interventions and specialist treatments among list of recommendations

The rising number of working days lost to mental illness creates huge personal suffering and huge costs to the economy, and more needs to be done to help people with mental illness stay in work.

The rising number of working days lost to mental illness creates huge personal suffering and huge costs to the economy, and more needs to be done to help people with mental illness stay in work.

This is the principal message of Chief Medical Officer Dame Sally Davies in her latest annual report, this year focusing on the mental health of the nation. The report also highlights problems caused by alcohol and addictions, and states that the integration of wider mental health care with addictions care provision is particularly important.

With the number of working days lost to stress, depression and anxiety increasing by 24% since 2009, the CMO has called for NICE to analyse the cost benefit of fast-tracking access to treatment for working people who may fall out of work due to mental illness. Rapid access to treatment could improve people’s chances of staying in work.

The CMO also recommends simple changes to help people with mental illness stay in work by offering flexible working hours and employers making early and regular contact with employees on sick leave.

The report also finds that:

- 75% of people with diagnosable mental illness receive no treatment at all. CMO reinforces calls for parity of funding with the acute sector for mental health services and for waiting time targets for mental health services to be developed by NHS England

- There is a need for greater focus on mental health care for children and young people. 50% of adult mental illness starts before age 15 and 75% by age 18. Early treatment for young people can help to prevent costly later life problems including unemployment; substance misuse; crime and antisocial behaviour.

Culture change needed

On the importance of addressing addictions, the report says that a cultural change is required within the NHS and social care organisations to combat stigma and discrimination against people with addiction problems, and to ensure equity of care and delivery of effective interventions to address addiction problems and related health problems. Active participation of all healthcare staff is crucial to discharge responsibilities of duty of care – both duty to detect and duty to act.

Increasing the penetration of alcohol screening, brief interventions for hazardous and harmful drinkers and specialist treatment for people with alcohol dependence would have a major public health impact in reducing alcohol-related ill health and costs to society in England.

However, the report says that currently only a small minority of people with alcohol dependence access specialist alcohol treatment, even though their condition requires more specialist care. Special integrated care is required for high-morbidity complex cases. In South East London this has been supported by the development of a shared NHS alcohol strategy between the acute and mental health trusts, and academic and community stakeholders. This has included a fast track admissions pathway for patients with complex alcohol problems between A&E and the specialist inpatient addictions unit and assertive outreach services for frequent alcohol related hospital attenders.

In terms of public health interventions, increasing the price of alcohol is the most cost-effective and targeted measure to reduce harmful drinking, and has been endorsed by both NICE and WHO. Setting a minimum unit price below which alcohol cannot be sold would have the greatest possible impact on reducing alcohol-related harm in England.

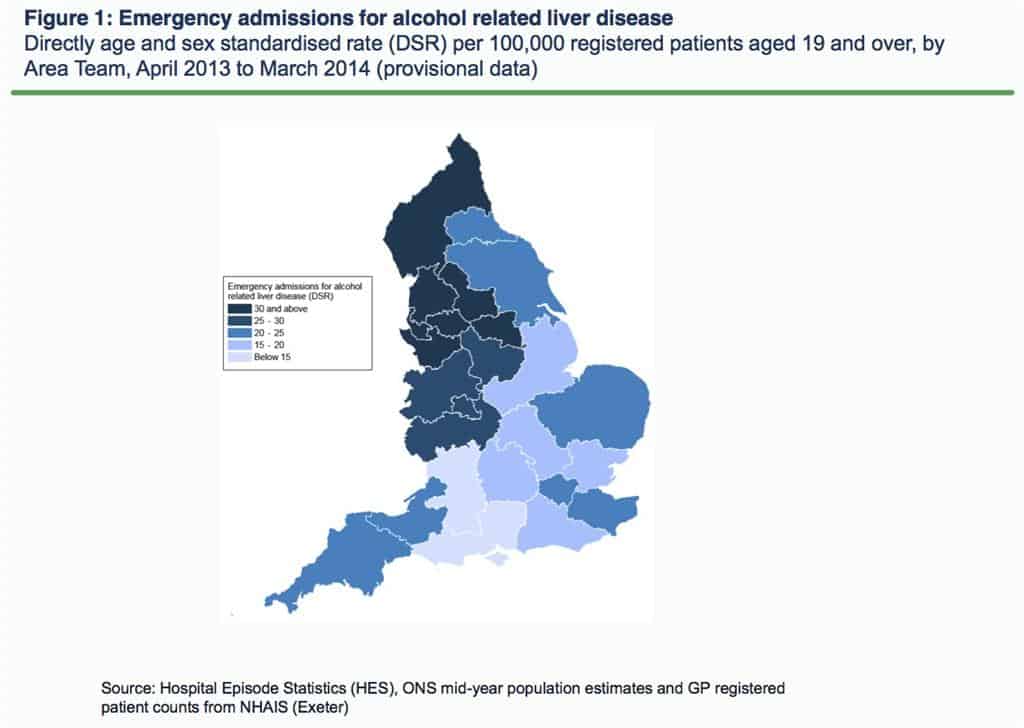

Alcohol-related liver disease: new map highlights regional hotspots

National average equates to just

over 200 hospital admissions every week

Areas of the North West and North East of England have the

highest rate of emergency hospital admissions for alcohol-related liver disease

in the country, new figures show.

The Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) has

today published a regional map

of emergency admissions per 100,000 of the adult population alongside new data at

national, Area Team and Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) level.

The provisional data shows that, nationally, hospitals

admitted 10,500 cases of alcohol-related liver disease between April 2013 and

March 2014 – equating to just over 200 admissions a week.

Regionally, the Area Teams with the highest rate of

emergency hospital admissions among the adult population in the same time

period were:

- Greater Manchester at 45.8 admissions per 100,000 of the

population (1,010 admissions in total – or just over 19 per week on average) - Merseyside at 41.3 admissions per 100,000 of the population

(414 admissions in total – or about eight per week on average) - Lancashire at 38.9 admissions per 100,000 of the population

(472 admissions in total – or about nine per week on average)

The Area Teams with lowest rate were:

- Bath, Gloucestershire, Swindon and Wiltshire at 14.7

admissions per 100,000 of the population (182 admissions in total – or just under

four per week on average) - Wessex at 14.7 admissions per 100,000 of the population (330

admissions in total – or about six per week on average) - Hertfordshire and the South Midlands at 15.1 admissions per

100,000 of the population (335 admissions in total – or about six per week on

average)

HSCIC Chair Kingsley Manning said: “This map paints a

powerful picture of one of the many impacts that alcohol has on patients and

the NHS in this country. This one image depicts what the hundreds of rows of

data published today mean for different areas of England.

“While many will be familiar with the HSCIC’s annual

alcohol statistics, fewer people may be aware we also publish a myriad of

different health and social care indicators about different conditions and care

on a regular basis.

“The data we have presented today about alcohol related

liver disease is the first such provisional data for 2013/14 to be published at

such a local level. It should act as basis to help the NHS commission services

effectively.”

This article was taken from the HSCIC press release. The CCG Emergency admissions for alcohol related liver disease map forms part of the CCG Outcomes Indicator Set.

Liver disease: a preventable killer of young adults

Professor Julia Verne, Public Health England

Liver disease has changed over the years but my commitment to reducing deaths hasn’t.

I’ve had a fascination and passion for treating and preventing it since I was a medical student, training at the Royal Free School of Medicine under Dame Professor Sheila Sherlock who was the founder of liver disease as a speciality.

As a junior doctor I worked on both medical and surgical liver units, assisting in the first transplant conducted at the Royal Free when liver transplantation in the UK was in its infancy.

I vividly remember the terrible suffering of patients with end stage liver disease, coming in as an emergency, vomiting vast quantities of blood from oesophageal varices or with huge pregnant looking bellies distended with ascites which had to be drained. Patients were restricted to drinking very small quantities of water and eating virtually no salt. Others suffered psychoses or coma and then multiple organ failure resulting from their end stage liver disease.

In those days we didn’t wear gloves because we didn’t want to upset patients and make them feel untouchable. Hepatitis C had not yet been discovered and our options were very limited.

Since then, we know about Hepatitis C, Hepatitis B can be subtyped there are new treatments for both. There are 600-700 transplants per year and liver disease has gone from being a rare disease to one seen frequently in every hospital and general practice.

But though treatments have improved we have to tackle the increase in disease which is mainly preventable. There are also large inequalities in liver disease – it is a no brainer that as a Public Health Physician, I see that we should be making a concerted effort to reverse these trends.

Here are some hard facts:

- Liver disease is the only major cause of mortality and morbidity which is on the increase in England, whilst it is decreasing among our European neighbours

- Over a decade the number of people dying with an underlying cause of liver disease in England rose by 40% from 7,841 to 10,948

- Most liver disease deaths are from cirrhosis (a hardening and scarring of the liver) or its complications – people die from liver disease at a young age with 90% under 70 years old and more than 1 in 10 in their 40s

- Liver disease is the third biggest cause of premature mortality and lost working life behind ischaemic heart disease and self-harm

- Most liver disease is preventable – only about 5% of deaths are attributable to autoimmune and genetic disorders – over 90% are due to three main risk factors: alcohol, viral hepatitis and obesity

- It’s a disease of inequalities. Mortality rates from liver disease in people aged 75 years and under varied significantly by Primary Care Trust. People who live in the most deprived fifth of areas in England are more likely to die from liver disease than those who die in the most affluent fifth.

- Liver disease, and death from it, is associated with stigma mainly because of the risk factors. This sometimes makes it hard for the patients to access care and hard for the families especially in bereavement

- 70% of patients with liver disease die in hospital and while one in five of those who die have had five or more admissions to hospital in the last year of life one in five are admitted only once and die in that first admission and 4% die in A&E without getting admitted to hospital. This reflects the often dramatic complications accompanying death from liver disease.

With these statistics in mind it’s unsurprising that liver disease has received a high profile over the past few years. In 2014, The Chief Medical Officer devoted a chapter to liver disease recommending a need for preventative measures involving a combination of public health policy initiatives and increased awareness of liver health and the risk factors for liver disease among the public.

The All Party Parliamentary Hepatology Group Inquiry into Improving Outcomes in Liver Disease produced their report ‘Liver Disease: today’s complacency, tomorrow’s Catastrophe’, earlier this year. The Lancet also launched a commission on Liver Disease which will publish its findings and recommendations this autumn.

Following a meeting between the chairs of the APPG, liver charities and PHE, independently it was agreed that PHE would produce a framework outlining its scope of activities to tackle liver disease. I am leading the co-ordination of this framework which will involve input from colleagues across all PHE departments and directorates, as well as input from the liver charities and Directors of Public Health in local authorities. PHE has extensive programmes of work to tackle all three major risk factors; alcohol, viral hepatitis and obesity.

On the 16th October, PHE will publish Liver Disease Profiles for local authorities in England. These will support the work of Health and Wellbeing Boards and Joint Strategic Health Needs Assessments by providing vital information about liver disease prevalence in their areas.

The challenge will be significant. Liver disease develops silently and obvious signs and symptoms may only appear when changes are irreversible, therefore the identification of people with risk factors for liver disease in primary care is a critical first step in the pathway.

Many patients come from marginalised groups with unstable accommodation, many don’t speak English and many may have difficulty attending or sticking to treatment because of addiction to alcohol and or drugs.

Article reproduced with kind permission of Public Health England

“Being drunk is no excuse for sexual harassment on nights out; it’s time to put a stop to it.”

Being drunk is not an excuse for sexually harassing or assaulting other people. This criminal behaviour should not be tolerated; if it’s not acceptable sober, it’s not acceptable drunk

This is the message of the alcohol industry-funded charity Drinkaware as it pursues a renewed education and communications strategy following a review of binge drinking in the night-time economy. The commissioned review, `Drunken nights out: motivations, norms and rituals in the night time economy’, was designed to further understanding of the meaning and purpose of binge drinking for those who participate in it, allowing the development of more sophisticated strategies to challenge attitudes and behaviour.

This is the message of the alcohol industry-funded charity Drinkaware as it pursues a renewed education and communications strategy following a review of binge drinking in the night-time economy. The commissioned review, `Drunken nights out: motivations, norms and rituals in the night time economy’, was designed to further understanding of the meaning and purpose of binge drinking for those who participate in it, allowing the development of more sophisticated strategies to challenge attitudes and behaviour.

The review highlights that drunkenness is an integral part of a night out for many young people. 82% of 18-24 year olds who drink will always or almost always drink alcohol when they go out; 35% said that, when they go out, those occasions are always or most often drunken nights out.

Half of young people questioned in the survey (50%) said a typical night out involves drinking with friends before going out. For almost a third, it also means playing drinking games (32%) and 27% describe a typical night out as one where they lose count of how much they’ve had to drink.

However, the review concludes that the widely used term ‘binge drinking’ is problematic. This is because definitions are inconsistent; there is a credibility gulf between recommended and actual consumption, a focus on quantities consumed neglects the social nature of drinking and drunkenness,and the term is associated with unhelpful stereotypes shaped by attitudes to class,gender and, in particular, youth.

The review argues that behaviour during drunken nights out is, in fact, highly structured – in contrast to common representations as chaotic, reckless and out of control. The structuring role of social norms and rituals is particularly important. Moreover, a drunken night out is undertaken, not by individuals, but by groups of friends.

These considerations underlie the Drinkaware approach. This will focus on four aspects: Boundaries, what is considered socially acceptable; Conscience, for example relation to perceived group safety; Consequences, and Vulnerability.

However, the review concludes that education and communication strategies alone are unlikely to bring about real change, and that Drinkaware’s activities, therefore, need to be accompanied by other approaches by other organisations.

Sexual Molestation

The Drinkaware message on sexual molestation relates to the first aspect of drunken behaviour identified, boundaries. The message highlighting the extent of unwanted sexual attention on drunken nights out and tolerance of this criminal behaviour was launched to coincide with Freshers’ Week.

However, it was stressed that it’s not just students who are affected. Nearly a third of young women (31%) aged 18-24 said they received inappropriate or unwanted physical attention or touching on a drunken night out in a survey conducted by ICM for Drinkaware. Very few (19%) of those who have experienced this said they were surprised when it happened to them. In addition, more than a quarter of young women (27%) have put up with inappropriate sexual comments or abuse on a drunken night out.

Most young people (66%) said that persistent unwanted sexual attention ruins a good night out. Young women who experienced this said that unwanted attention on a night out made them feel disgusted (69%); they also reported feeling anger (56%) and fear (39%).

Adrian Lee, Chief Constable, Northamptonshire Police and national policing lead on alcohol harm for the Association of Chief Police Officers supported the Drinkaware initiative. He said:

‘The consequences of excessive drinking are witnessed across the country in the hospitals and police stations of our towns and cities every week. Drunken Nights Out is a significant piece of research that identifies for the first time the routines and rituals of young people as they enjoy a weekend of socialising and partying. Pre-drinking plays a significant part of these rituals and we know that those who pre-drink are two and a half times more likely to be involved in violence and four times more likely to consume over 20 units in a night. This research provides real insight into pre-loading and binge drinking, providing real opportunity for police and partners to develop effective ways to challenge and influence irresponsible drinking to help keep people safe and healthy.

Report: ‘Drunken nights out: motivations, norms and rituals in the night time economy’

Acute Care Alcohol Health Workers

Report evaluates the effectiveness of alcohol health workers in hospitals

A new study of alcohol health workers (AHWs) has found that while many hospitals now employ specialist staff to deal with alcohol problems among patients, the work is often precarious and underfunded. The study also found that currently there is limited evidence of their effectiveness.

A new study of alcohol health workers (AHWs) has found that while many hospitals now employ specialist staff to deal with alcohol problems among patients, the work is often precarious and underfunded. The study also found that currently there is limited evidence of their effectiveness.

In its 2012 Alcohol Strategy, the Government stated that hospital-based alcohol health workers played a ‘vital’ role in improving the future health of patients, and called for more alcohol liaison nurses to be employed. However, the report, funded by Alcohol Research UK and carried out by researchers from Leeds Beckett University and the University of York, concludes that while positive steps are taking place, more investment and better research is needed to support this important role.

Dr Sarah Baker from Leeds Beckett University – and formerly with the University of York – carried out the research with Charlie Lloyd, from York’s Department of Health Sciences.

Dr Baker said: “Hospital-based alcohol health workers are integral to the successful delivery of preventative and treatment-based alcohol intervention. On-going financial and managerial support needs to be in place to ensure that these positions have the necessary resources to achieve their full potential.”

The research

AHWs are specialist staff working in hospital – usually nurses – who identify and work with patients drinking at levels that may impact or have already impacted their health. While a range of policy documents, including the Government’s Alcohol Strategy (in England) recommend the expansion of AHW provision and it is clear that there has been a rapid spread of such posts across the acute care sector, there has been very little recent research exploring their nature and coverage.

The new report provides an overview in regard to AHW provision and its main conclusion is that the position of AHWs can be characterised as precarious. This is for a number of reasons. First, they are relatively new and many are still responding to initial problems and finding their place within the hospital. Second, partnership funding was the most common funding arrangement (36% of services surveyed) and this could lead to a lack of clear ownership of the service. This was particularly problematic when Acute Trusts had no financial involvement. Third, funding was short-term and insecure. Fourth, some AHWs were poorly managed and felt invisible and isolated.

While 94% of responding hospitals had a dedicated AHW, hospitals without an AHW may have been less likely to respond and so this may be an overestimate. Services included in the survey represented considerable variation. The number of AHWs per hospital varied between 0.6 and 6 FTE. While the number of AHWs was correlated with the number of alcohol-related hospital admissions, it was by no means a complete explanation. The majority of services were available between 9am and 5pm on week days, although some services covered evenings (38%) and weekends (42%).

AHWs covered a range of roles, including screening and brief interventions, liaison with outside agencies, education, detoxification, protocol and care pathway development, follow-up and discharge planning, and management of ‘frequent fliers’ (patients who are repeatedly admitted to hospital). However, there was variation in how AHWs spent their time across these tasks. There was a tendency for AHWs to migrate up the alcohol problem ladder, focusing increasingly on dependent drinkers. 71% of the patients seen by AHWs were dependent drinkers.

It was hard for AHWs to monitor their work effectively. While screening figures could be relatively easily collected, the complex work done with dependent drinkers was harder to measure. Measuring outcomes was very difficult for all aspects of their work.

Implications

The precarious nature of AHW services raises questions about whether, and how, these services could be given a firmer footing. The Government’s Alcohol Strategy simply ‘encourages’ all hospitals to employ Alcohol Liaison Nurses, but this may not be encouragement enough if a minimum national service is to be developed. Given strong financial pressures and the immediacy of ill-health and disease, the more preventive role played by AHWs may require financial incentives from the centre.

The variability in provision raises questions about standardisation. Of course, local services need to reflect local needs. However, the considerable variation in AHW provision does not simply reflect local needs: it is likely to reflect the presence or absence of local champions and the degree to which alcohol is taken seriously by commissioners. There may be worth in drawing up minimum requirements for AHW teams – or alcohol teams – in hospitals.

An important issue here is the strength of the evidence base. If AHWs convincingly were shown to decrease admissions and save money, the argument for a properly resourced service is greatly strengthened. While the multi-faceted nature of their role and the frequently delayed nature of their impact makes outcome evaluation challenging, nonetheless this should be a priority for future research.

More immediately, there seems to be a clear need for better management and peer support. There is a worrying tendency for AHWs to feel undervalued and isolated in their posts. It may be that this is partly a consequence of the cross-cutting nature of the role, which is largely peripatetic. However, proper ownership of AHW services by NHS hospital trusts, with attendant management would be likely to go some way towards improving this situation.

Conclusion

There are clear indications, not just from the present study (Thom et al., 2013), that the extent of AHW provision has greatly increased in recent times, reflecting the rising saliency of alcohol as a pressing health issue. However, the evidence from this study suggests that provision is variable and precarious. The time seems to be ripe for a proper review of the AHW function and how it can be properly supported and integrated within the hospital setting. However, it is difficult to make a strong case for AHW provision when the evidence-base is weak. Evaluating multi-faceted services such as those provided by AHWs is challenging but there is a pressing need for more outcomes research in this field.

One in six women drivers admit to drink driving whilst over the limit

Report finds that many women underestimate the amount they can drink before they drive

Research conducted by Social Research Associates on behalf of Direct Line Car Insurance and the Rees Jeffreys Road Fund suggests that millions of women in the UK regularly consume alcohol and take to the roads.

The literature review which inspired the report ‘Drinking among British Women and its impact on their pedestrian and driving activities: Women and Alcohol‘ found that although overall rates of consuming alcohol are falling, drinking above the recommended limits is on the increase among affluent older women. There was also some evidence that women may be unaware of what constitutes a unit of alcohol, and how much they can drive after drinking without being above the legal limit.

Researchers followed up these findings by conducting face-to-face surveys of 430 women drivers who also drank alcohol in four areas: Brighton, Leicester, Newcastle, and Preston. 20 females convicted of driving over the prescribed limit were also interviewed, as well as a small control group of 45 men.

Key Findings

Of the core group of women drivers interviewed, four out of 10 (41 per cent) admitted to getting behind the wheel of a car after drinking alcohol. This was most common among young women drivers, with 47 per cent of 18–29 year-olds claiming to have done so.

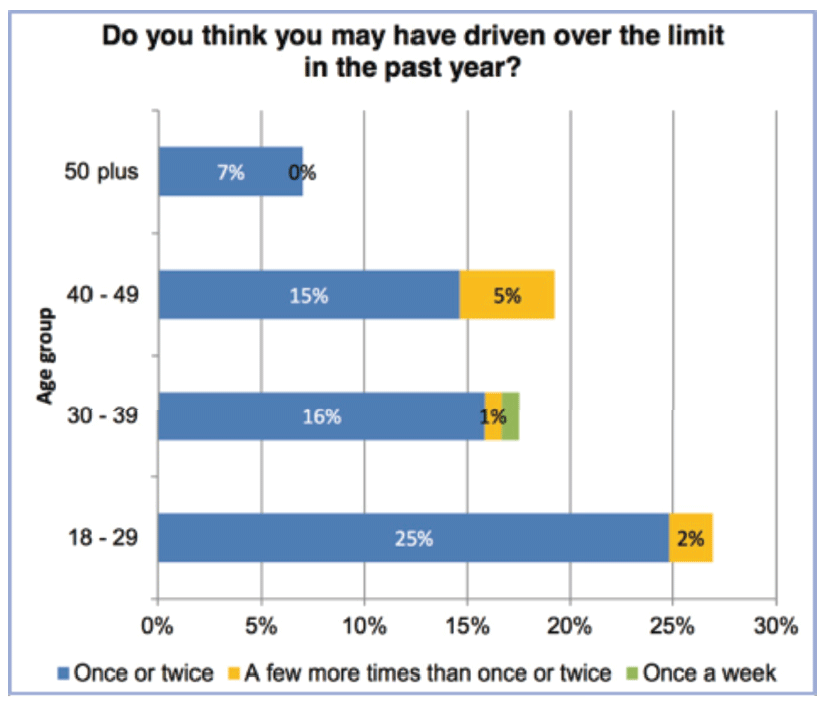

The same age group also represented the greatest proportion of the 17 per cent of female respondents who thought that they may have driven while over the drink-drive limit in the past year.

Frequency of driving when possibly over the legal limit within the past year, by age

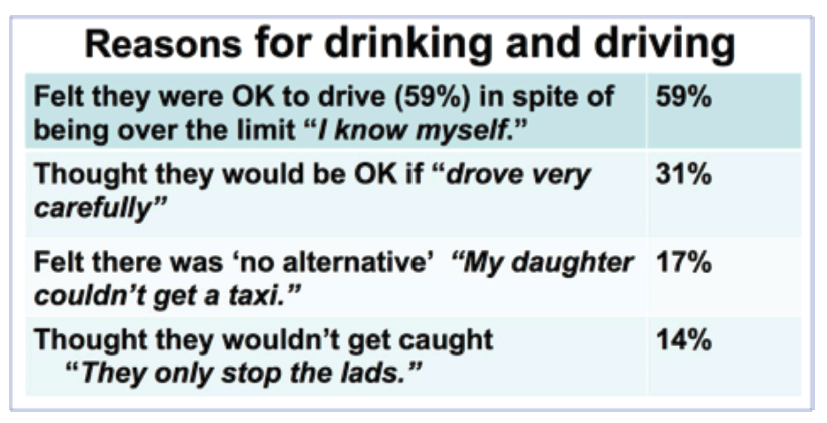

The most common reason given for driving over the legal limit was not necessity, but that they felt physically ‘OK to drive’ (59 per cent), meaning that the majority of women who thought that they may have driven while over the drink-drive limit believed that they could drive without incident or accident.

The notion that one could just ‘drive carefully’ (31 per cent) was the next most frequent explanation given by women drivers for driving while over the legal limit.

17 per cent felt they had no alternative other than to drink and drive, often due to ‘family emergencies’.

A further 14 per cent say they drove whilst over the limit because they thought there was little risk of being caught.

In almost all cases, respondents felt that they were personally able to drink more alcohol than the ‘average woman’ could before they were over the legal limit. This confident perception amongst respondents towards alcohol in general was emphasised by a lack of awareness in the risks of being over the limit.

The report noted that knowledge about how much alcohol women can drink before driving and remain under the legal blood alcohol limit was poor overall, and in some cases potentially inaccurate. Over a third of women in the survey said that they could drive legally after drinking a pint or more of beer, but at 5 per cent volume a pint would equate to 2.8 units, which could place at least some women at risk of a drink-drive offence. Almost 15 per cent of women thought that they could drink more than a standard (175 cc) glass of wine and still drive safely when that equates to at least 2 units.

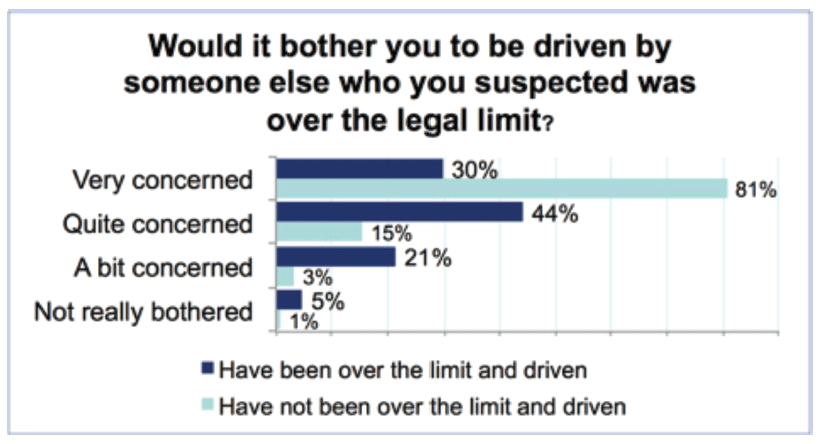

Respondents’ worries over the dangers of drink-driving were largely reserved for others. Almost all of those questioned (90 per cent) said they would be concerned or very concerned to be driven by someone who they thought was over the limit. However, women who thought that they had driven over the limit at some point were significantly less likely to be very concerned than those who had not (30% compared with over 80%).

Conclusions: More gender-specific data please

The results of the study highlighted the growing proportion of all drink driving convictions received by women, which has risen from 9 per cent in 1998 to 17 per cent in 2012. Another finding published in the report was that women are proportionately more likely to be over the legal limit as drivers than men from the age of 30.

The data provided by the survey answers indicates that this phenomenon may be due to a lack of understanding about both the legal drink-drive limits and the amount of alcohol that women could consume before it seriously impaired their own ability to drive. The authors believed that this was partly reinforced by the emphasis on drink and also anti-drink advertising which predominantly features men, and led to a view that women were relatively ‘under the radar’ in terms of being stopped and breathalysed.

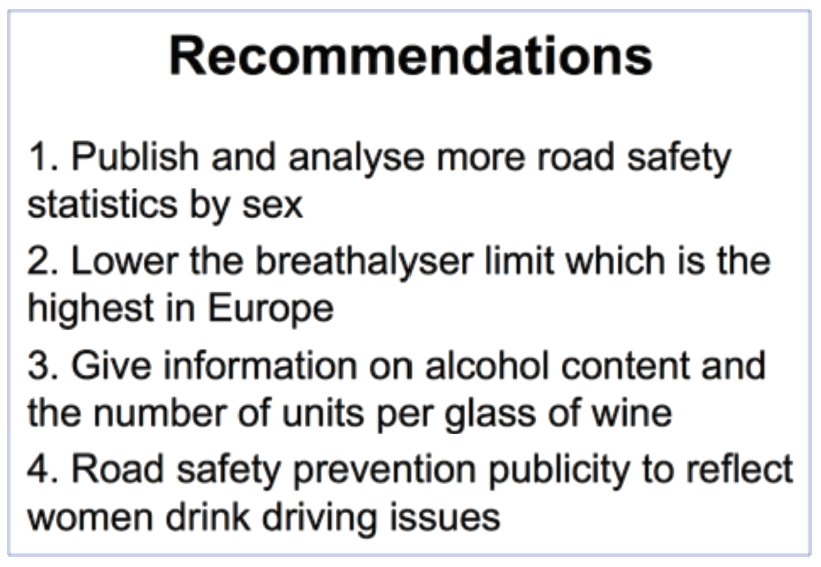

The project also led the authors to call for a greater emphasis on communicating how drinking alcohol seriously impairs driving ability, and that:

- driving ‘carefully’ is no solution to this

- getting caught is a real risk

- there is almost always an alternative to drink driving

Other notable recommendations made in the conclusions to the report’s literature review and surveys (see illustration) included an appeal for more drink-driving data to be routinely recorded and analysed by sex, as much existing research into drink-driving suffers from the problem of being ‘gender blind’, the authors claim.

Britons spend almost £50,000 on alcohol during their lifetime

Macmillan Cancer Support has highlighted the amount of money individuals spend on alcohol per year and during their lifetime as part of its Go Sober for October fundraising campaign. The charity is inviting people to seek sponsorship for giving up alcohol for the month of October and donating the proceeds.

The Macmillan investigation found that the average Briton spends almost £50,000 on alcohol, £787 per year, with those in London spending nearly an extra £100.

Men spent more on alcohol than women, spending an average of £934.44 per year compared to women who spend £678.60.

The findings also show that 1.3 million Britons spend £167,000 on alcohol during their lifetime.

Hannah Redmond, Head of National Events Marketing for Macmillan Cancer Support, said: “By taking part in Go Sober for October, abstaining from drinking alcohol for the month of October and being sponsored to do so, you’ll save money, reap the health benefits and raise vital funds to support people affected by cancer so they don’t have to face it alone.”

Macmillan point out that the money saved by not drinking for 12 months would be enough to buy:

1. A six-island Caribbean cruise (£749)

2. iPhone 6 (£699)

3. One-night stay for two at the Shangri-La Hotel in The Shard, London (£540)

4. Mulberry Tassie tote bag (£595)

5. Two-night spa break at Champneys with two treatments (£609)

6. Glastonbury Festival tickets and glamping in a tepee for two (£750)

7. A Man Utd FC season ticket (£722)

8. A 48-inch HD TV (£700)

137,000 litres of alcohol seized in UK during Europe-wide crackdown

HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) has seized illicit alcohol and disrupted alcohol-related criminal gangs as part of a Europe-wide initiative tackling international organised crime

Europol intelligence-led operation Operation Archimedes – spearheaded in the UK by HMRC – used intense activity to disrupt alcohol smuggling across northern European countries and into the UK, with support from the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Germany and Italy.

Europol intelligence-led operation Operation Archimedes – spearheaded in the UK by HMRC – used intense activity to disrupt alcohol smuggling across northern European countries and into the UK, with support from the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Germany and Italy.

HMRC, working together with Border Force, Trading Standards and Kent Police, seized 137,124 litres of illegal alcohol during the operation, which took place between Monday 15 September and Thursday 19 September 2014.

This included:

- 132,940 litres of beer seized (almost a quarter of a million pints)

- 260 litres of spirits seized (more than 300 bottles of spirits)

- 3,924 litres of wine seized (more than 4,000 bottles of wine)

- 7 vehicles seized

John Pointing, Assistant Director of Criminal Investigation for HMRC, said:

“Alcohol smuggling costs the UK economy around £1 billion a year in lost revenue. HMRC is committed to tackling alcohol crime and this month’s action has had an outstanding impact in bringing law enforcement agencies across the UK and Europe together to disrupt one of the most serious organised criminal threats.

“We encourage anyone with information regarding alcohol smuggling and fraud to contact the Customs Hotline on 0800 59 5000.”

More than 250 HMRC officers, as well as officers from partner agencies in the UK and across Europe, took part in the operation targeting alcohol smuggling at UK ports (Dover, Tilbury, Purfleet) and inland at 23 locations including alcohol retail units, haulier truck stops, industrial units and warehouses across England. Colleagues in The Netherlands, Belgium, France, Germany and Italy took similar action at their borders, lorry parks and storehouses where they suspected the movement of illicit alcohol, and “ghost” bonded warehouses.

Abolition of beer duty escalator boosts beer consumption

The beer industry has produced a special-edition beer, ‘George’s Budget Booster’, in celebration of Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne’s abolition of the beer duty escalator.

The industry says that reducing the tax on beer has boosted beer sales by 500 million pints, and created 16,000 jobs ‘at very little cost to the Government.’ The figures are contained in a report ‘Cheers 2014’, commissioned from Oxford Economics jointly by the British Beer and Pub Association, CAMRA and the Society of Independent Brewers. The report was presented to Chancellor George Osborne at the Conservative Party Conference, along with the new, special-edition beer.

Cheers 2014 forecasts that, in 2015, an additional 16,000 more people will work in the beer and pub sector than if the duty escalator had remained in place. It claims that, as well as boosting beer sales, the move has resulted in an extra £44 million in capital investment (alongside over £400 million already planned) into the brewing and pub sector.

The report claims that duty cuts have led to renewed optimism across the sector. The BBPA surveyed brewers and pub operators after the March 2014 Budget to assess the impact of the Chancellor’s decision. Over three-quarters of respondents intended to launch new products, across both beer and pubs, directly as a result of the cut in beer duty.

The wider supply chain and economy is also benefiting markedly. In the BBPA survey, over 90% of respondents intend to increase their investment in the UK.

However, the figures are likely to be challenged. While there is no question that sales of beer have indeed increased since the abolition of the escalator, providing further evidence that affordability is one of the major determinants of alcohol consumption, the claims regarding additional jobs are speculative forecasts, seemingly based on the opinions of people in the beer industry rather than on hard data. An earlier European study found that there was no direct relationship between levels of alcohol consumption and the number of jobs provided by the alcohol industry.

Government “has turned its back on public health”

The duty escalator, first introduced by the Labour Government in 2008, required alcohol duties to rise 2% above inflation, automatically, each year. It was seen, at the time and subsequently, as the key measure to reduce the burden of alcohol harm, and there is evidence to suggest that, over time, the escalator was helping to reduce the number of deaths related to alcohol.

When George Osborne abolished the escalator, he was accused of turning his back on public health. The decision to abolish the escalator followed on from the Coalition Government’s reneging on its promise to introduce the Minimum Unit Pricing of Alcohol as the central plank of its Alcohol Harm Reduction Strategy.

As reported in a previous issue of Alcohol Alert, Professor Sir Ian Gilmore, Chair of the Alcohol Health Alliance and the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) special adviser on alcohol, condemned the move unequivocally:

“To suggest scrapping the duty escalator at a time when current levels of alcohol tax revenue do not even meet half the cost of alcohol-related harm to our society is deplorable. Parliament has been absolutely right to support the duty escalator since 2008 – it has played an important role in addressing the affordability of cheap alcohol that creates an enormous burden on society. Government needs to stand strong on this issue – the taxpayer is already paying too much to foot the bill of alcohol-related harm, now is not the time to scrap the alcohol duty escalator. Society simply cannot afford it.”

David Cameron – 2012: “We can’t go on like this. We have to tackle the scourge of violence caused by binge drinking … and that means coming down hard on cheap alcohol.”

Katherine Brown, Director of the Institute of Alcohol Studies, described the decision to scrap the escalator as ‘staggering’, saying that it indicated the Government had turned its back on public health. She continued: “With alcohol costing the country £21 billion a year, and alcohol-related hospital admissions more than doubling over the last ten years, it comes as a shock to learn that the Chancellor believes that it is right to incentivise drinking further by making alcohol cheaper.”

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

Gambling industry harms and parallels with the alcohol world

Will Prochaska –

Coalition to End Gambling Ads