In this month’s alert

Editorial – September 2017

Welcome to the September 2017 edition of Alcohol Alert, the Institute of Alcohol Studies newsletter, covering the latest updates on UK alcohol policy matters.

This month, Pubs call for action on cheap supermarket alcohol, according to the findings from our ‘Pubs Quizzed‘ report. Other articles include: study finds industry misleading the public about alcohol links with cancer, as media coverage of alcohol during pregnancy is also found to mislead in parts; and Facebook trial alcohol ad blocking for users.

Please click on the article titles to read them. We hope you enjoy this edition.

TOP STORY: Pubs call for action on cheap supermarket alcohol

Four-fifths of pub managers say supermarket alcohol is too cheap

Pubs Quizzed’ report |

01 September – British publicans see cheap supermarket alcohol as the single greatest threat to their industry, and support government action to raise prices, according to a new Institute of Alcohol Studies (IAS) report.

Pubs Quizzed: What Publicans Think About Policy, Public Health and the Changing Trade collects the results of a national survey of pub managers, finding that a large majority (83%) believe supermarket alcohol is too cheap, with almost half (48%) citing competition from shops and supermarkets among their top three biggest concerns. Almost three-quarters (72%) of publicans believe the government should raise taxes on alcohol in supermarkets to tackle the problem.

These findings highlight divisions in the alcohol industry, with several major multinational producers actively opposing policies such as minimum unit pricing (MUP), which would increase the price of the cheapest products sold in shops and supermarkets. Legislation for MUP was passed by the Scottish Government in 2012, but implementation continues to be delayed as a result of a legal challenge by the Scotch Whisky Association, which represents firms such as Diageo and Pernod Ricard. However, Pubs Quizzed finds ordinary publicans support the measure by a margin of two to one, with 41% in favour and 22% against.

Commenting on the findings of this report, IAS chief executive Katherine Brown said:

“The desire to support pubs has often been used as a reason to resist policies to reduce alcohol-related harm, including minimum unit pricing, increasing alcohol taxes and stricter drink-drive laws. However, Pubs Quizzed finds that publicans actually favour many of these measures, recognising cheap alcohol as a danger both to their business and to wider society.”

The report’s author, IAS policy analyst Aveek Bhattacharya, said:

“Supermarkets and off-licences emerged as the clear villains from our interviews with publicans. There is a widespread belief that they are undercutting local pubs and encouraging harmful drinking. Our findings suggest that whether you want to support pubs or to reduce harmful drinking, the answer is the same: increase the price of the cheapest alcohol through tax or minimum unit pricing.”

Other findings include:

- 44% of publicans feel that the UK has an unhealthy relationship with alcohol

- 58% of publicans in England and Wales support reducing the drink-drive limit to bring them into line with Scotland

- Business rates are more unpopular than alcohol taxes, with 38% ranking higher rates among the top three biggest threats to their business, compared to 17% for higher alcohol taxes

- Publicans are generally optimistic about the state of the industry, with 53% predicting that this year will be better than the last

You can listen to author Aveek Bhattacharya discuss ‘Pubs Quizzed‘ in more detail by following our Alcohol Alert podcast.

28% of adults ‘can’t enjoy holiday without alcohol’

Adapted from Press Association

06 September – More than a quarter (28%) of adults find it “impossible” to enjoy a holiday without alcohol, according to a new study.

The survey by travel search firm Kayak also revealed that 10% of people have previously spent more on alcohol while on holiday than the cost of flights and accommodation.

The figures emerged amid growing concern about drunken airline passengers causing disruption on flights.

Some 58% of those who drink more whilst on a break say it is “part of going on holiday”, and a third (33%) claim they “have more fun” when they have been drinking.

Kayak commissioned a survey of 2,001 UK adults who had been on holiday in the past two years.

Excess alcohol has led to holidaymakers getting into problematic situations, with 7% admitting they have suffered an injury after drinking, 6% forgetting where their hotel was and 5% vomiting on themselves.

Kayak travel expert John-Lee Saez said: “It’s perhaps not a huge surprise that Brits enjoy a drink or two whilst on holiday.

“It is our time to relax and in many cases a week or two where we don’t have to worry about our day-to-day responsibilities like our job or housework.

“But as the research shows, it is all too easy to get carried away when under the influence, so I’d advise Brits to take care not to get carried away with their drinking on holiday – especially those at all-inclusive destinations.

“You may not pay for the alcohol in cash, but you could end up paying for it by doing something silly or ruining the day after with an awful hangover.”

The number of people arrested for drunken behaviour on flights or at UK airports increased by 50% in the last year, a recent BBC Panorama investigation found.

Most of the UK’s major airports and airlines signed up to a voluntary code of conduct in 2016, pledging to limit or stop the sale and supply of alcohol if there are concerns about disruptive behaviour.

Most ill heavy drinkers would drink a third less under MUP

Scottish study “adds unique dimension” to current evidence

07 September – Over two-thirds of heavy drinkers who seek help for their alcohol misuse would drink a third less on average if a 50 pence minimum unit price (MUP) was introduced in Scotland, say researchers from Edinburgh Napier University.

According to their study, published in Alcohol and Alcoholism journal, details of the quantities of alcoholic drinks purchased in the last week by the 639 patients attending alcohol treatment services or admitted to hospital with an alcohol-related condition were projected forward to estimate future consumption.

For the 69% who purchased only off-sale alcohol at below MUP, their consumption was estimated to fall 33% on average. For other drinkers there might be no reduction, especially if after MUP there were many products priced close to 50p per unit.

Roughly 15% of patients purchased from both the more expensive on-sale outlets (hotels, pubs, bars) and from off-sales (shops and supermarkets). For them, the researchers estimated the change in consumption that might follow MUP either if they continued the same proportion of ‘on-sales’ purchasing, or if their reported expenditure was moved entirely to off-sale purchasing, in order to maintain the same levels of consumption.

The researchers concluded that by focusing specifically on “harmed drinkers”, their data addresses “an important gap within the evidence base informing policy.

Industry misleading the public about alcohol-related cancer risk

Adapted from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine website

08 September – The alcohol industry is misrepresenting evidence about the alcohol-related risk of cancer with activities that have parallels with those of the tobacco industry, according to new research published in the journal Drug and Alcohol Review.

Led by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine with the Karolinska Institutet, Sweden, the team analysed the information relating to cancer which appears on the websites and documents of nearly 30 alcohol industry organisations around the world between September 2016 and December 2016. Most of the organisational websites (24 out of 26) showed some sort of distortion or misrepresentation of the evidence about alcohol-related cancer risk, with breast and colorectal cancers being the most common focus of misrepresentation.

The most common approach involves presenting the relationship between alcohol and cancer as highly complex, with the implication or statement that there is no evidence of a consistent or independent link. Others include denying that any relationship exists or claiming inaccurately that there is no risk for light or ‘moderate’ drinking, as well discussing a wide range of real and potential risk factors, thus presenting alcohol as just one risk among many.

According to the study, the researchers say policymakers and public health bodies should reconsider their relationships to these alcohol industry bodies, as the industry is involved in developing alcohol policy in many countries, and disseminates health information to the public.

Alcohol consumption is a well-established risk factor for a range of cancers, including oral cavity, liver, breast and colorectal cancers, and accounts for about 4% of new cancer cases annually in the UK. There is limited evidence that alcohol consumption protects against some cancers, such as renal and ovary cancers, but in 2016 the UK’s Committee on Carcinogenicity concluded that the evidence is inconsistent, and the increased risk of other cancers as a result of drinking alcohol far outweighs any possible decreased risk.

This new study analysed the information which is disseminated by 27 alcohol industry-funded organisations, most commonly ‘social aspects and public relations organisations’ (SAPROs), and similar bodies. The researchers aimed to determine the extent to which the alcohol industry fully and accurately communicates the scientific evidence on alcohol and cancer to consumers. They analysed information on cancer and alcohol consumption disseminated by alcohol industry bodies and related organisations from English speaking countries, or where the information was available in English.

Through qualitative analysis of this information they identified three main industry strategies. Denying, or disputing any link with cancer, or selective omission of the relationship, Distortion: mentioning some risk of cancer, but misrepresenting or obfuscating the nature or size of that risk and Distraction: focussing discussion away from the independent effects of alcohol on common cancers.

Strategies

A common strategy was ‘selective omission’ – avoiding mention of cancer while discussing other health risks or appearing to selectively omit specific cancers. The researchers say that one of the most important findings is that industry materials appear to specifically omit or misrepresent the evidence on breast and colorectal cancer. One possible reason is that these are among the most common cancers, and therefore may be more well-known than oral and oesophageal cancers.

When breast cancer is mentioned the researchers found that 21 of the organisations present no, or misleading, information on breast cancer, such as presenting many alternative possible risk factors for breast cancer, without acknowledging the independent risk of alcohol consumption.

Professor Petticrew said: “Existing evidence of strategies employed by the alcohol industry suggests that this may not be a matter of simple error. This has obvious parallels with the global tobacco industry’s decades-long campaign to mislead the public about the risk of cancer, which also used front organisations and corporate social activities.”

The researchers say the results are important because the alcohol industry is involved in conveying health information to people around the world. The findings also suggest that major international alcohol companies may be misleading their shareholders about the risks of their products, potentially leaving the industry open to litigation in some countries.

Women and alcohol: What’s next?

Last in seminar series

08 September – The Royal College of Physicians played host to the fourth Women and Alcohol seminar, ‘Women and Alcohol: What’s next?‘, the final of the series. Hosted by the Institute of Alcohol Studies (IAS) and Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems (SHAAP), speakers and participants took the opportunity to discuss and address possible solutions to the issues raised throughout the series.

Chair Dr. Sally Marlow posed three key questions for discussion:

1) How will women be affected by alcohol in the future?

2) How can alcohol-related harms to women be prevented and/or reduced?

3) How do we strike a balance between individual responsibility and state intervention?

IAS chief executive Katherine Brown began the discussion, exploring key alcohol-related harms disproportionately impacting women – including breast cancer – in light of recently published work documenting the alleged downplaying of such health harms by some industry sites. In addition, Brown wondered whether social harms might become normalised through advertising practices – a serious issue, given the highly gendered dimension of much alcohol marketing.

Maria Piacentiti, professor of Consumer Behaviour at Lancaster University spoke next, presenting work exploring social media and alcohol. She raised the use of gendered, sexualised imagery, combined with drinks promotions, in nightclub marketing, and suggested that User Generated Content might serve to further embed these ideas.

ADFAM’s Vivienne Evans closed the session, noting the need for more female-focused treatment services. Further, she proposed the notion of ‘passive drinking’; that alcohol problems are not confined to drinkers and these passive harms might fall disproportionately on women.

A report summarising the findings of the series will be released in the near future. Follow @InstAlcStud and @SHAAPALCOHOL for further details.

Our very own Chief Exec @VivEvans47 speaking about impact of alcohol on women at @InstAlcStud & @SHAAPALCOHOL #WomenAndAlcohol event https://t.co/sK9W3lq44c

— Adfam (@AdfamUK) September 8, 2017

‘Misleading coverage’ of pregnancy drinking risks from media

Researchers insist there is no safe amount of alcohol

12 September – Bristol University researchers behind a recent study into the impact of low levels of alcohol consumption during pregnancy have hit out at the “misleading” way that their findings were presented in national newspapers. Whereas reports in several national newspapers implied that drinking during pregnancy can be harmless, the researchers emphasised that their results should not be taken as contradicting the Chief Medical Officers’ guidance that it is safest not to drink during pregnancy.

The row began with the publication of a systematic review carried out by Loubaba Mamluk and colleagues in the journal BMJ Open. Prompted by last year’s revision of the Chief Medical Officers’ guidelines, from advising that alcohol consumption during pregnancy should be restricted to ‘one to two UK units, once or twice a week’ to recommending avoiding alcohol altogether, the review sought to understand whether there was any clear evidence to support such a shift. They therefore reviewed studies that compared the outcomes for mothers drinking under four units per week (and so compliant with the old guidelines) and mothers abstaining altogether (and so compliant with the new guidelines).

The primary finding of the review was that there are a “surprisingly limited” number of studies addressing this question, and the authors were unable to draw robust conclusions about the impact of light drinking on many of the outcomes they were seeking to investigate, such as requiring assisted delivery, hypertension and developmental delays. Based on the studies that were reviewed, the analysis found that consumption of up to 4 units per week increased the risk of delivering a baby small for their gestational age. However, it also found that drinking had no statistically significant impact on the chances of premature birth or of low birth weight.

On the basis of these results, the authors conclude that there is “a paucity of evidence demonstrating a clear detrimental effect, or safe limit, of light alcohol consumption” during pregnancy. They accept that for many the revision of the guidelines to recommend abstinence is an appropriate precautionary measure, on the basis of animal experiments and the undisputed negative effects of higher levels of consumption. However, they suggest that such recommendations should be accompanied by clearer acknowledgement of the lack of evidence supporting them and more open justification of the guidelines on the basis that ‘absence of evidence is not evidence of absence’.

Major newspapers reported the study as showing drinking during pregnancy was safe. The Times put the story on its front page under the headline “Light drinking ‘does no harm in pregnancy’”. The Daily Mail presented it as a rebuke to the drinking guidelines under the headline “‘No proof’ that the odd glass of wine harms your baby, despite Government advice to abstain while pregnant”.

According to NHS Choices, “Media reporting of the study was generally accurate and responsible, making it clear that it’s probably still best to avoid alcohol during pregnancy”. Indeed, the BBC and The Sun both observed that the researchers endorsed the existing guidelines in the third paragraph of their reports. The Daily Mail article made the same point, though not until its eighth paragraph, despite referring to the guidelines in its headline.

However, The Times’ reporting of the research received substantial criticism. Luisa Zuccolo, one of the authors of the study, penned an angry open letter accusing the newspaper of “misinformation” and “gross misrepresentation”, pointing to their suggesting drinking does “no harm”, as well as a comment article in the paper by Alice Thompson who claimed it “now appears acceptable in moderation”. “Such misreporting may boost newspaper sales, but does not benefit public health… Today’s unborn babies won’t be buying copies of your paper anytime soon, but one day this misreporting could cost them and the nation looking after them, very dearly”, wrote Zuccolo. Cambridge statistics professor David Spiegelhalter also condemned the article as “dire”. Spiegelhalter had issued a quote saying: “A precautionary approach is still reasonable, but with luck this should dispel any guilt and anxiety felt by women who have an occasional glass of wine while they are pregnant.” However, The Times (and The Sun) cut out the first part of his quote, removing his point about the precaution.

In response, The Times issued a correction, recognising: “We wrongly suggested in a headline that a recent scientific study had concluded that “light drinking does no harm in pregnancy”. While the study found little evidence that light drinking in pregnancy is harmful, it also found little evidence that it is safe, and — as we made clear in our report — its authors support guidance advising abstention as a precautionary principle.”

Mixed picture for new liver disease atlas of England

Eight-fold differences in disease rates between Blackpool and Norfolk

14 September – New data published by Public Health England (PHE) show that liver cirrhosis hospital admissions rates have doubled over the past decade, while premature mortality rates from liver disease vary significantly across the country has widened over the past decade.

Liver disease is almost entirely preventable with the major risk factors, alcohol, obesity and Hepatitis B and C, accounting for up to 90% of cases. The 2nd Atlas of Variation in risk factors and healthcare for liver disease in England comes as PHE publishes an online resource outlining a strategy for health professionals to help allocate their resources to improve patient outcomes.

The Atlas shows premature mortality rates – dying before the age of 75 – ranged from 3.9 per 100,000 in South Norfolk clinical commissioning group (CCG) to 30.1 per 100,000 in Blackpool CCG, a 7.7-fold difference.

The Atlas is made up of 39 indicators, 19 of which show trend data over time. Ten displayed improvements, including a reduction of premature deaths and fewer alcohol-specific hospital admissions for under 18s. However, nine of the indicators have become worse over time, including a doubling of hospital admission rates for cirrhosis from 54.8 per 100,000 to 108.4 per 100,000 people over the past decade. This indicator also varies significantly across the country with an 8.5-fold variation across CCGs, and this gap has widened over the past decade.

Liver disease is responsible for almost 12% of deaths in men aged 40 to 49 years and is now the fourth most common cause of ‘years of life lost’ in people aged under 75, after heart disease and lung cancer.

Professor Julia Verne, Head of Clinical Epidemiology at PHE said:

Stark health inequalities

The Atlas also lays bare the impact of the stark health inequalities in England. Inequality plays a role in the significant variation in risk factors of liver disease – excessive alcohol consumption, obesity, and hepatitis B and C.

For example, there is a 7.4-fold difference in the rate of alcohol-specific hospital admissions across the country, with the majority of the higher rates being clustered in the more deprived areas. Also, in the most deprived fifth of the country, people with liver disease die nine years earlier than those in the most affluent fifth.

Vanessa Hebditch, director of communications and policy at the British Liver Trust, told The Telegraph: “Across the UK we are facing a liver disease crisis.

“People are dying of liver damage younger and younger, with the average age of death now being mid-50s.

“It is also becoming more and more common for liver units to have much younger individuals waiting for a liver transplant or dying on the wards.

“This data shows that not only do we need to ensure that there are excellent and consistent liver services across the country but that people need to be diagnosed much earlier to obtain effective care, treatment and support as soon as possible.

“This means that primary care needs to have a much greater emphasis on liver disease.”

PHE ‘All Our Health’ factsheet |

‘All Our Health’ PHE strategy

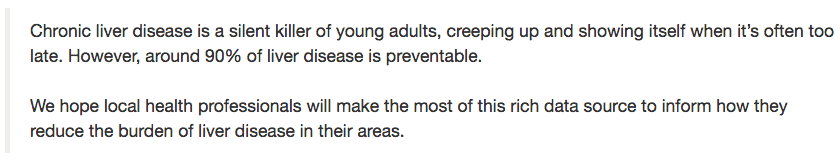

In the face of new liver disease figures added to the estimated 10.4 million adults who drink at levels that pose some risk to their health (illustrated), PHE have also published a new online resource detailing the range of strategic and intervention level approaches available to improve population health.

James Morris in Alcohol Policy UK writes that PHE’s ‘All Our Health’ strategy aims to “maximise the impact healthcare professionals in England can have on improving health outcomes and reducing health inequalities”, with alcohol identified as one of the key indicators in health improvement owing to the 10.4 million adults drinking above the low risk guidelines.

The resource states healthcare professionals should ‘be aware that different degrees of alcohol misuse will require different levels of intervention and understand specific activities that can prevent, protect, and promote’, and breaks down interventions as those which can be applied at local population, community, and family and individual levels.

Europeans gaining taste for alcohol-free beer

Beverage increasing in popularity across continent

MINTEL infographic on |

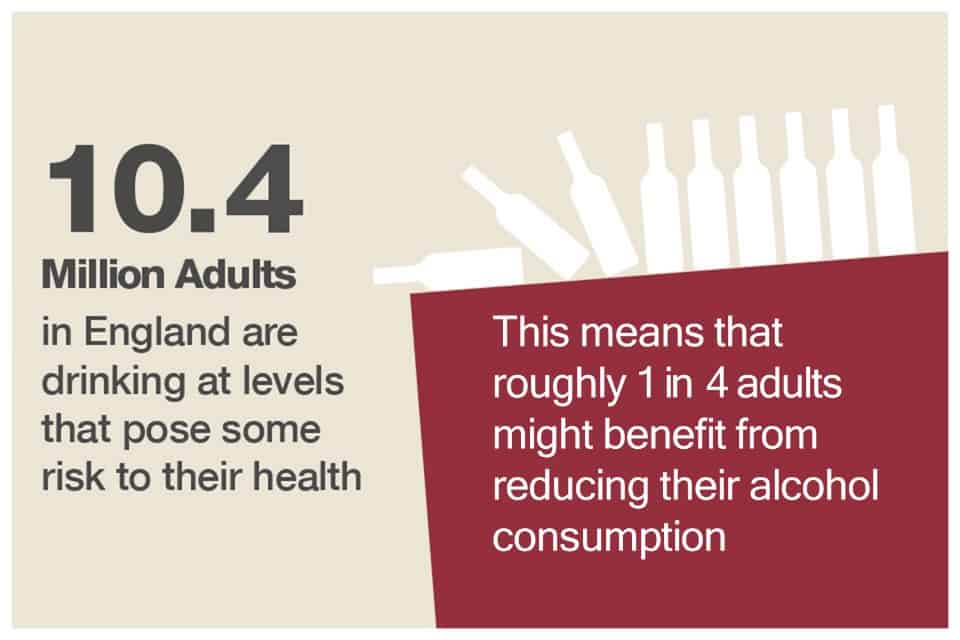

15 September – Market researchers Mintel have released the results of a survey that may give brewers something to think about ahead of Oktoberfest.

Sample groups of between 1,000 and 2,000 people surveyed in Germany, Poland, Italy, Spain and France via Lightspeed showed a developing taste for the lighter tipple. More than a quarter of German consumers (27%) agree that low/no alcohol beer tastes just as good as full-strength beer, and three in ten Germans aged 18-24 (31%) agree that low/no alcohol beer tastes just as good as ‘regular’ beer (4-6% ABV).

The stigma appears to be draining away too: just 9% of Germans say they would be embarrassed to be seen drinking low / no alcohol beer.

The Polish were the most likely to extol the virtues of low or no alcohol beer with 43% saying it tasted just as good as full strength. Italy and Span were joint second at 34%. And in France, where 28% thought all beers were created equal, 56% agreed that low or no alcohol beer allows you to stay in control of your drinking.

“Control has become a key watchword for today’s younger drinkers. Unlike previous cohorts, their nights out are documented through photos, videos and posts across social media where it is likely to remain for the rest of their lives. Over-drinking is therefore something many seek to avoid,” said Jonny Forsyth, Mintel’s Global Food & Drink Analyst.

However, while European interest is high, China is the most prolific global innovator of low/no alcohol beer product launches, according to Mintel Global New Products Database (GNPD). More than one in four (29%) beers launched in China in 2016 contained low/no alcohol, compared to one in ten launched in Spain (12%), Germany (11%) and Poland (9%). Meanwhile, the global average sits at just 8%. Low/no alcohol is defined as ABV below 3.5%.

“Looking to the future, the global beer market will see even more moderate innovation as Millennials, in particular, seek healthier and less calorific beer options. This goes hand-in-hand with a number of brands working to raise the quality of the product, especially non-alcoholic beers,” said My Forsyth.

“The German market is producing high quality, non-alcoholic beer and, as a result, it has now become a mainstream option. German beer drinkers may not have a history of moderation, but this is changing,” he added.

Communication of alcohol guidelines ‘needs to be improved’

Only 8% of people know what the low-risk weekly guideline actually is

19 September – A study published today concludes that more needs to be done to communicate the drinking guidelines to the public.

The study, published in the Journal of Public Health, found that one month after the release of the current drinking guidelines, only 8% of people knew what the low-risk weekly guideline was.

This is despite the fact that most of the public were aware that new guidelines had been issued.

The current low-risk weekly guideline, drawn up by the UK’s Chief Medical Officers and released in January 2016, is 14 units spread out across the week for both men and women.

This equates to roughly six pints of regular strength beer, or six medium glasses of wine.

The report found that two-thirds of the public believe it is the government’s responsibility to communicate the guidelines.

It also found, in a positive development, that nine in ten people agree with the official guidance that if you are pregnant or trying to become pregnant, the safest approach is not to drink.

Commenting on the report, Professor Sir Ian Gilmore, chair of the Alcohol Health Alliance UK (AHA), said:

“It is worrying that, a month after the release of the drinking guidelines, only 8% of the public were aware of the low-risk weekly drinking guideline of 14 units a week, spread out across the week.

“As the report makes clear, more needs to be done to ensure the public are aware of the guidelines. The public have the right to know about the guidelines, and about the risks linked with alcohol including cancer, heart disease and liver disease, so that they can make informed choices about their drinking.

“The government needs to make sure that all alcohol labels contain the current low-risk weekly drinking guideline of 14 units for both men and women. Labels should also carry warnings of the specific illnesses linked with alcohol, and point people towards independent health advice on alcohol, like the websites of Public Health England and the NHS.

“The government should also develop public campaigns communicating the guidelines across TV, radio, the press and online. In addition, the government should make sure all healthcare professionals are aware of the current drinking guidelines and the evidence behind them, so that they can communicate this information to patients.

“We also welcome the fact that nine out of ten people in this study agreed with the official advice that it is safest not to drink whilst pregnant or whilst trying to become pregnant.”

Facebook trial lets users hide alcohol adverts

Like? No, hide

20 September – Social media giant Facebook is testing a tool that lets people hide advertisements for alcohol, the first time any social network has let people proactively block adverts on a specific topic.

During the Facebook trial, participants will be able to block alcohol-related ads for six months, a year to permanently, by accessing their ad preferences.

The move has been welcomed by Alcohol Research UK, which says social media is “saturated” with alcohol promotions. Dr James Nicholls, director of research and policy development at the organisation, told BBC Radio 5 Live that the volume of marketing material on social media was a particular problem for those who had struggled with alcohol misuse.

Alcohol adverts on all platforms are governed in the UK by a system of co-regulation involving the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) and a self-regulatory code of practice produced by the Portman Group, the alcohol industry funded responsibility

body for drinks producers in the UK.

The ASA rejected claims that regulation around alcohol adverts online needed reviewing.

Craig Jones, the organisation’s spokesman, insisted that the rules were applied “just as stringently online – including ads on social media, user-generated content and vlogs – as they are in traditional media.

“The number of complaints we receive about alcohol ads has halved in recent years, but we’re not complacent and keep the rules under constant review. If people see an alcohol ad they think is irresponsible they can make a complaint to the ASA. If an ad breaks the rules, one complaint can be enough to see it banned.”

Magic pill to cure alcoholism is make believe

Review of five prescription drugs finds “no clear evidence of benefit”

21 September – Pills prescribed by doctors for those suffering from alcohol dependence might not work, says a study published in Addiction journal.

The scientific review of five drugs – nalmefene, naltrexone, acamprosate, baclofen, and topiramate – has found that no reliable evidence exists for their effectiveness. This is despite nalmefene being approved for use in the NHS by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and baclofen being widely used in France.

The pills have been developed for people who have not stopped drinking completely and are intended to help them cut down, with a view to reducing the harm they are doing to their bodies. However, the study found that the pills had a low- or medium-level effect on the amount people were drinking.

Effectiveness unknown

The scientists looked at 32 double-blind (i.e. both control group and test group participants remain unknown to the researcher and participants) randomised controlled trials representing 6,036 patients, published between 1994 and 2015.

The researchers wrote: “the rationale for using pharmacologically controlled drinking stems from the idea that if individuals reduce their total alcohol consumption, they reduce their levels of risk accordingly.

“Other consumption outcomes were considered as secondary outcomes, namely:

- The number of heavy drinking days;

- The number of non-drinking days;

- The number of drinking days and;

- The number of drinks per drinking day.”

However, the dropout rate across all 32 trials was so high that 26 were declared to have unclear or incomplete outcome data (resulting in a notable attrition bias), 17 trials were considered to present an unclear or a high risk of selective outcome reporting, and all 32 trials lacked consensus on the ways of measuring and / or reporting outcomes too.

Lead author Dr Clément Palpacuer from Inserm, the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research, told The Guardian: “Although our report is based on all available data in the public domain, we did not find clear evidence of benefit of using these drugs to control drinking. That doesn’t mean the drugs aren’t effective; it means we don’t yet know if they are effective. To know that, we need better studies. Researchers urgently need to provide policymakers with evidence as to which of these drugs can be effectively translated into a real harm-reduction strategy.”

This finding follows a study published last year in which researchers from the University of Stirling concluded that “the evidence for the efficacy of nalmefene in reducing alcohol consumption in those with alcohol dependence is, at best, modest, and of uncertain significance to individual patients”. Nalmefene was the first drug of its kind to be licensed in Europe.

The drug baclofen has been given a provisional licence in France, pending the results of more trials, because it is being widely used. Yet a Dutch study last year said it may work no better than counselling and there have been reports of deaths linked to the drug.

Do “digital interventions” reduce heavy drinking?

FaceTime, or face-to-face time?

25 September – Personalised advice given via computer or mobile devices may be better than nothing for helping to reduce heavy drinking, but make no difference compared to face-to-face conversation, claim researchers in the Cochrane Review.

The evidence base suggests that the amount people cut down following one of these digital interventions may be roughly 1.5 pints of beer, or a third of a bottle of wine.

So the research team compared advice provided using a computer or mobile device with the alternatives, i.e. no or minimal intervention, and face-to-face conversation, to see which technique was most effective at reducing heavy drinking.

Heavy drinking causes over 60 diseases, as well as many accidents, injuries and early deaths each year. Brief advice or counselling, delivered by doctors or nurses, is said to help people reduce their drinking by around 4 to 5 units a week, the equivalent of around two pints of typical strength beer or half a bottle of wine. However, people may be embarrassed by talking about alcohol.

Who was involved?

The studies included people in workplaces, colleges or health clinics and internet users. Everyone typed information about their drinking into a computer or mobile device – which then gave half of them advice about how much they drank and the health effects. This group also received suggestions about how to cut down on drinking. The other group could sometimes read general health information. Everyone was asked to confirm how much they were drinking at time points from one month and up to one year later.

Results

The team looked at 57 studies comparing the drinking of 34,390 people getting advice about alcohol from computers or mobile devices with those who did not after one to 12 months. Of these, 41 studies (42 comparisons, 19,241 participants) focused on the actual amounts that people reported drinking each week. The results showed that compared to no or minimal interventions:

Most people using a digital intervention reported drank approximately three fewer units of alcohol per week

15 studies (n = 10,862) showed that they gained some drink-free hours per month (but less than a single day in total)

Another 15 studies (n = 3,587) showed about one binge drinking session less per month in the intervention group

Only five small studies (n = 390) compared digital and face-to-face interventions. There was no difference in alcohol consumption at end of follow up. Therefore there may be little or no difference between both techniques to reduce heavy drinking.

Dearth of data

That the evidence was noted as moderate-to-low quality, was symptomatic of a dearth of data. The research team wrote:

“There was not enough information to help us decide if advice was better from computers, telephones or the internet to reduce risky drinking.” Furthermore, the team admitted that they “do not know which pieces of advice were the most important to help people reduce problem drinking.”

However, they suggested that advice from trusted people such as doctors “seemed helpful”, as did recommendations that people “think about specific ways they could overcome problems that might prevent them from drinking less and suggestions about things to do instead of drinking.”

ALCOHOL SNAPSHOT: Public Health England highlight geographical inequalities in the burden of alcohol

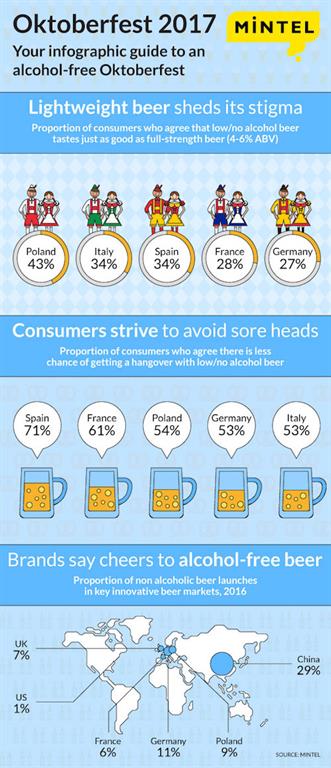

Variation in rate of alcohol-specific admissions in people of all ages per CCG, 2015/16 (Directly standardised rate per 100,000) |

The North-East, the North-West and parts of London suffer the highest rates of illness due to alcohol, according to Public Health England (PHE) analysis. By contrast, rates of harm are below average across most of the Midlands, South and East of the England.

The chart above comes from PHE’s 2nd Atlas of Variation in risk factors and healthcare for liver disease in England, published earlier this month. This forms part of PHE and NHS England’s ‘Atlas of Variation’ project, which seeks to understand regional health inequalities, and attempts to provide local level service providers with high quality data, which can help them to identify areas of success and issues to address.

The chart maps the rate of hospital admissions for alcohol-specific conditions for each of the English Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs – the regional NHS bodies responsible for planning and commissioning of health services within their local area). It shows vast disparities in outcomes, with the rates of hospitalisation due to alcohol seven times higher in some parts of the country compared to others. Moreover, this inequality has been widening over time: where ten years ago the gap between the 95th and 5th percentile was 574 hospitalisations per 100,000, it has risen to 740.

The report suggests a number of options for action for health service providers seeking to reduce the rate of alcohol-specific hospitalisations in their area, including integrating harm prevention, treatment and recovery initiatives, learning best practice from other areas, appointing alcohol health workers, implementing identification and brief advice and seeking to influence change through advocacy and national social marketing campaigns.

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

Gambling industry harms and parallels with the alcohol world

Will Prochaska –

Coalition to End Gambling Ads