View this report

Summary

- According to the 2011 Census, one in five people in England and Wales belong to an ethnic group other than White British.

- Generally, people from ethnic minority groups drink less and are more likely to abstain from alcohol than their White British counterparts. However, there are relatively high rates of higher risk drinking among certain groups, for example older Irish men and men belonging to the Sikh religion.

- People belonging to ethnic minority groups may be less likely to access alcohol treatment services, and often do not seek help for alcohol use until they have experienced serious health consequences. There are multiple barriers to seeking help that are experienced by ethnic minorities, with some barriers specific to certain higher-risk groups, such as Irish Travellers.

- Some ethnic minority groups experience more alcohol harm. For example, White Irish men experience higher rates of alcoholic liver disease and other alcohol-related diseases, and Sikh men experience higher rates of liver cirrhosis.

- Ethnicity is one aspect of an individual’s identity, and overlaps with other aspects of identity and life circumstances. Alcohol consumption and support needs in some groups are not well understood, and there has been little research to understand ethnic minority groups’ experiences of alcohol’s harm to others. Clinical trials of interventions have not regularly reported on recruitment of people from ethnic minorities or the outcomes across different ethnic groups.

Introduction

According to the 2011 Census, one in five people in England and Wales belong to an ethnic group other than White British [1].

There is considerable diversity within as well as between ethnic groups. There is also variation in alcohol consumption and harm by overlapping aspects of identity such as age, gender, religion, migration status, location, and socio-economic circumstances. Some of these other aspects of identity are covered elsewhere on the IAS website.

This briefing is focused on the UK and uses the term ‘ethnic minorities’ to refer to all ethnic groups except the White British group, in line with the UK Government style guide [2,3]. We recognise that ethnic minorities in the UK are the global majority, and that individuals often prefer to refer to their specific ethnic identity.

This briefing is a summary of alcohol consumption, alcohol treatment and alcohol harm among people from ethnic minority groups. Key gaps in knowledge are also highlighted.

Alcohol consumption and higher risk drinking

Data on both alcohol consumption and ethnicity are collected annually across the UK as part of the Health Survey for England, Scottish Health Survey, National Survey for Wales, and Health Survey Northern Ireland. However, the breakdown by ethnic group is not routinely presented in the reports and data tables published annually. This is partly due to small numbers in some groups, meaning the prevalence is not reliable.

A 2019 rapid evidence review conducted for Alcohol Change UK identified higher rates of abstention from alcohol among people from ethnic minorities. However, there are relatively high rates of higher risk drinking among certain groups, for example older Irish men and men belonging to the Sikh religion [4].

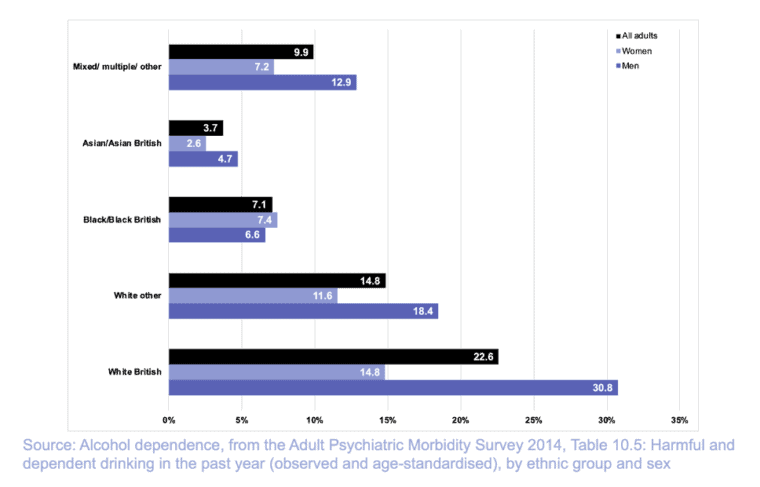

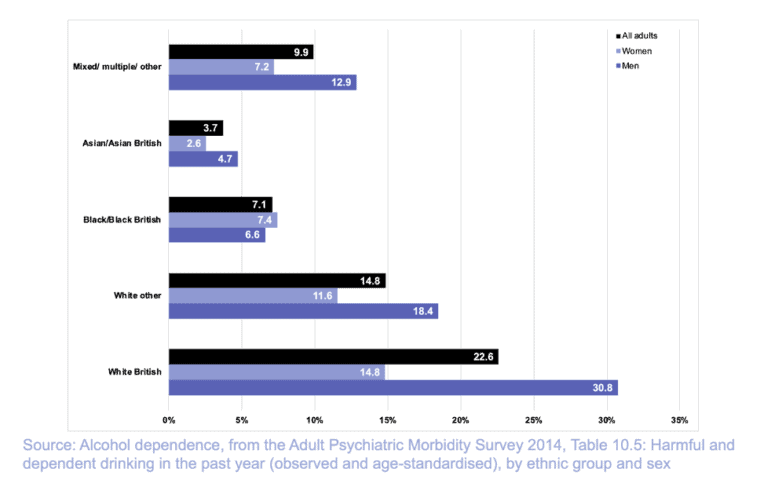

Nationally-representative age-standardised estimates of the prevalence of drinking at hazardous, harmful or dependent levels* by broad ethnic group among adults in England are available from the 2014 Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey [5]. White British adults were more likely to drink at levels classed as hazardous, harmful or dependent compared with adults from all other ethnic groups. Harmful and dependent drinking was also most common in the White British group (see figure 1).

Figure 1 Percentage of adults drinking at hazardous, harmful or dependent levels by ethnicity and sex (APMS 2014, age-standardised)

Figure 2 Percentage of adults drinking at harmful or dependent levels by ethnicity and sex (APMS 2014, age-standardised)

The Scottish Health Survey years 2008-11 were combined in a special report on equality groups in 2012 [6]. White British (40%) and White Irish respondents (41%) were most likely to have exceeded the daily limit** on their heaviest drinking day in the past week. The White Other group was significantly less likely (27% of respondents) to drink above limits than the national average (39%). Other ethnic minorities were less likely to drink above the daily limits, with 19% of African, Caribbean or Black respondents and 4% of both Pakistani and Chinese respondents having done so [7].

A 2019 study found ethnic minorities have lower levels of alcohol consumption compared to White British groups, no matter the generation, but this gap is narrowed among second generation ethnic minorities [8]. Differences in alcohol consumption across different ethnic groups were previously attributed to culture and religion, and changes over time understood through processes of acculturation [9]. More recently it has been suggested that alcohol consumption or abstinence may be one way for individuals to identify with, or reject, societal definitions of their ethnicity [10]. This topic and generational differences in alcohol consumption among ethnic minorities is discussed in detail in the 2019 rapid evidence review for Alcohol Change UK [11].

Similar patterns are also seen among adolescents. Among 11-15-year-old school pupils in England in the 2018 Smoking, Drinking and Drug Use Survey, White pupils were most likely to have had an alcoholic drink in the last week (13%), compared with 7% of Mixed ethnicity pupils, 3% of Black pupils and only 1% of Asian pupils [12]. Ethnic diversity is likely to only explain a small amount of the decline in alcohol consumption among UK adolescents in recent decades [13].

Alcohol treatment

The 2019 rapid evidence review conducted for Alcohol Change UK found that people belonging to ethnic minority groups are less likely to access services, and may be less likely to seek help for alcohol use until they have experienced serious health consequences [14].

The National Drug Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS) collects information on ethnicity of clients entering treatment for substance use disorders in England. Among ‘alcohol only’ clients*** in treatment in 2018/19 (73,420 individuals), 93% were White, 3% were Asian/Asian British, 2% were Black/African/Caribbean/Black British and 1% belonged to Mixed/Multiple ethnic groups. Among ‘non-opiate and alcohol’**** clients (27,792 individuals), the pattern was broadly similar: 90% of clients were White, 4% of clients were Black/African/Caribbean/Black British, 3% of clients were Mixed/Multiple, 2% Asian/Asian British, and 1% Other ethnic group [15].

Regarding how the increased prevalence of higher risk drinking among Sikh men is reflected in alcohol treatment, the NDTMS statistics are also available by religion. In 2018/19, 1% of ‘alcohol only’ clients identified as Sikh [16] (in the 2011 Census, 0.8% of the population identified as Sikh) [17].

The ethnic groups reported in the NDTMS are broad, so it is difficult to explore how the increased likelihood of higher risk drinking among certain minority groups (eg Irish groups) is reflected in alcohol treatment. In the 2011 Census, 0.9% of the population of England and Wales identified as White Irish and a further 0.1% identified as Gypsy or Irish Traveller [18]. Irish Travellers are a White ethnic minority group who experience poor physical and mental health [19], and face marginalisation, discrimination, illiteracy and poverty [20]. Irish Travellers have an increased likelihood of higher risk drinking, particularly among men and unmarried women [21,22]. Qualitative studies have identified a lack of understanding of alcohol dependence, and the downplaying of problematic use patterns among Irish Travellers [23,24]. Poor health literacy and low awareness of the kinds of support available mean Irish Travellers’ may not access drug and alcohol services [25].

More generally, barriers to seeking help faced by people from ethnic minorities include low awareness of health implications of excessive drinking, not being aware what support is available, difficulties navigating services and problems not being recognised by professionals, stigma and exclusion, lack of trust in the confidentiality of services, and community shame and stigma, especially among communities where there is a religious restriction on alcohol (eg Islam) [26]. These barriers are explored in detail, along with facilitators, support needs, and current interventions and services available in the 2019 rapid evidence review [27].

Alcohol harm

Inequalities in alcohol harm across ethnic groups may not necessarily reflect patterns in self-reported consumption. For example, differences in the acceptability of drinking alcohol in different groups may influence what individuals disclose in surveys. Accessing alcohol treatment is influenced in similar ways. This means it is important to also look at alcohol harm.

A 2016 study in Scotland examined ethnic differences both for alcoholic liver disease and alcohol-related diseases***** by linking NHS hospital admissions and mortality records with the Scottish Census 2001. For alcoholic liver disease, White Irish men had a 75% higher risk compared with White Scottish men. Other White British men had about a third lower risk of alcoholic liver disease, as did Pakistani men. For alcohol-related diseases, almost twofold higher risks existed for White Irish men and Any Mixed Background women compared with their White Scottish counterparts. Lower risks of alcohol-related disease existed in Pakistani and Chinese men and women [28].

Two earlier studies looked at alcohol-related mortality by country of birth (a different measure than ethnicity) for people living in both England and Wales and Scotland. In England and Wales, higher rates of mortality were seen amongst men born in Ireland, Scotland and India, and women born in Ireland and Scotland [29]. Lower alcohol-related mortality was observed in women born in other countries and men born in Bangladesh, Middle East, West Africa, Pakistan, China and Hong Kong, and the West Indies [30]. The same study found higher rates of mortality from hepatocellular cancer, which is closely linked to alcohol use, amongst men and women born in Bangladesh, China and Hong Kong, West Africa and Pakistan [31]. However it is unclear if this was related to other environmental and social factors beyond alcohol use. A similar study of Scottish residents found mortality from direct alcohol-related causes were comparatively low for people born in Pakistan, other parts of the UK and those from elsewhere in the world [32].

Sikh men are over-represented in liver cirrhosis statistics [33,34]. Sikhism is a religion and not included in the Census ethnic group categories (though individuals can self-identify if they wish), and Sikhs are often recorded as Indian ethnicity [35]. This highlights the importance of disaggregating ethnic minority groups, and exploring how different aspects of identity overlap.

Gaps in knowledge

Ethnicity is one aspect of identity, and overlaps with others, as well as indicators of social disadvantage or advantage. This is best described by the concept of intersectionality, which arose in Black feminist theory [36] and is used to describe the experience of multiple aspects of social disadvantage in relation to characteristics including (but not limited to) ethnicity, gender, socio-economic status, sexual orientation, age, and disability. Researchers using social surveys should carefully consider how ethnicity may overlap with other aspects of identity to avoid ‘spurious interpretations of the effects of ethnicity’ [37].

The 2019 rapid evidence review conducted for Alcohol Change UK found a lack of evidence around alcohol use and support needs particularly for ethnic minority women; ethnic minority prisoner populations; refugees and asylum seekers; LGBT individuals belonging to ethnic minority groups, and; non-practicing individuals from religious minorities [38]. Qualitative studies are well-suited to understand the experiences of such groups, and a new study funded by Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems has investigated experiences of harmful alcohol use among people seeking asylum and refugees in Scotland and England [39].

There is little evidence on how ethnic minorities experience indirect harms of alcohol and harms to others. However, in one multi-method study in emergency departments in England and Wales, alcohol intoxication was highlighted as an important factor in targeted violence, some of which was due to racism [40].

There is an absence of evidence around how interventions may work for ethnic minority groups, and there is uncertainty around the inclusivity of recruitment to intervention studies and trials. A 2020 systematic review examined the inclusion of women and ethnic minorities in randomised controlled trials of medications for alcohol use disorders. The review found that only 12% of trials reported full sex and racial/ethnic characteristics of their study participants, and only 6% of trials conducted subgroup analyses to examine differences in treatment outcomes by sex or ethnicity [41]. Greater efforts are therefore needed to include ethnic minorities (and women) in such studies, and to report on the inclusion, analysis, and reporting of data and outcomes by such groups [42].

* Based on the 10-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. A score of 0 to 7 indicates a non-drinker or low risk, 8 to 15 indicates hazardous drinking (a less serious problem with alcohol where the person might benefit from advice on ways to drink less), 16 to 19 indicates harmful drinking or mild dependence (a more serious problem with alcohol where the person would benefit from professional counselling to reduce alcohol consumption), and 20 or more indicates probable dependence and warrants further diagnostic evaluation and referral to a specialist.

** At the time the survey was conducted, the drinking guidelines were to not regularly exceed three to four units a day for men and two to three units a day for women.

*** Alcohol only: people who have problems with alcohol but do not have problems with any other substances. For more details see ‘Figure 1: How people are classified into substance reporting group’ in Adult substance misuse treatment statistics 2018 to 2019: report <https://bit.ly/3lZKVwp>

**** Non-opiate and alcohol: people who have problems with both non-opiate drugs and alcohol

***** Includes those that are wholly alcohol-attributable such as alcohol-related liver diseases, and chronic pancreatitis, poisoning, mental and behavioural disorders, nervous system, cardiomyopathy and gastritis due to alcohol.

- Gov.uk Ethnicity Facts and Figures Service. Population of England and Wales.

- Gov.uk. Writing about ethnicity.

- Bunglawala Z. Please, don’t call me BAME or BME! – Civil Service. 2019.

- Gleeson H, Thom B, Bayley M, McQuarrie T. Rapid evidence review: Drinking problems and interventions in black and minority ethnic communities. Alcohol Change UK. 2019

- Gov.uk Ethnicity Facts and Figures Service. Harmful and probable dependent drinking in adults. 2019.

- Whybrow P, Ramsay J, MacNee K. Scottish Health Survey – topic report: equality groups – gov.scot. 2012.

- Whybrow P, Ramsay J, MacNee K. Scottish Health Survey – topic report: equality groups – gov.scot. 2012.

- Wang S, Li S. Exploring Generational Differences of British Ethnic Minorities in Smoking Behavior, Frequency of Alcohol Consumption, and Dietary Style. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Jan; 16(12): 2,241

- Gleeson H, Thom B, Bayley M, McQuarrie T. Rapid evidence review: Drinking problems and interventions in black and minority ethnic communities

- Gleeson H, Thom B, Bayley M, McQuarrie T.

- Gleeson H, Thom B, Bayley M, McQuarrie T.

- NHS Digital. Smoking, drinking and drug use among young people. Part 5: Alcohol drinking prevalence and consumption. NHS Digital. 2019.

- Institute of Alcohol Studies. Youthful Abandon: Why Are Young People Drinking Less?. 2016.

- Gleeson H, Thom B, Bayley M, McQuarrie T. Rapid evidence review: Drinking problems and interventions in black and minority ethnic communities

- National Drug Treatment Monitoring System. NDTMS – Adult profiles: Ethnicity – England – Total – All in treatment to 2018-19.

- National Drug Treatment Monitoring System. NDTMS – Adult profiles: Ethnicity – England – Total – All in treatment to 2018-19.

- Religion in England and Wales 2011 – Office for National Statistics.

- Gov.uk Ethnicity Facts and Figures Service. Population of England and Wales.

- Parry G, Van Cleemput P, Peters J, Walters S, Thomas K, Cooper C. Health status of Gypsies and Travellers in England. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007 Mar; 61(3):198–204

- Van Hout MC. Alcohol use and the Traveller community in the west of Ireland. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010 Jan; 29(1): 59–63

- Van Hout MC. Alcohol use and the Traveller community in the west of Ireland

- Van Hout MC, Hearne E. The changing landscape of Irish Traveller alcohol and drug use. Drugs Educ Prev Policy. 2016 Jul 7; 24(2): 220–2

- Van Hout MC.

- Van Hout MC, Hearne E. The changing landscape of Irish Traveller alcohol and drug use

- Van Hout MC, Hearne E.

- Gleeson H, Thom B, Bayley M, McQuarrie T.

- Gleeson H, Thom B, Bayley M, McQuarrie T.

- Bhala N, Cézard G, Ward HJT, Bansal N, Bhopal R, Scottish Health and Ethnicity Linkage Study (SHELS) Collaboration. Ethnic Variations in Liver- and Alcohol-Related Disease Hospitalisations and Mortality: The Scottish Health and Ethnicity Linkage Study. Alcohol Alcohol Oxf Oxfs. 2016 Sep; 51(5): 593–601

- Bhala N, Bhopal R, Brock A, Griffiths C, Wild S. Alcohol-related and hepatocellular cancer deaths by country of birth in England and Wales: analysis of mortality and census data. J Public Health Oxf Engl. 2009 Jun; 31(2): 250–7

- Bhala N, Bhopal R, Brock A, Griffiths C, Wild S. Alcohol-related and hepatocellular cancer deaths by country of birth in England and Wales: analysis of mortality and census data

- Bhala N, Bhopal R, Brock A, Griffiths C, Wild S.

- Bhala N, Fischbacher C, Bhopal R. Mortality for Alcohol-related Harm by Country of Birth in Scotland, 2000–2004: Potential Lessons for Prevention. Alcohol. 2010 Nov 1; 45(6): 552–6

- Hurcombe R, Bayley M, Goodman A. Ethnicity and alcohol: a review of the UK literature. 2010 Jul 1.

- Douds AC, Cox MA, Iqbal TH, Cooper BT. Ethnic differences in cirrhosis of the liver in a British city: alcoholic cirrhosis in South Asian men. Alcohol and Alcoholism Oxf Oxfs. 2003 Apr; 38(2): 148–50

- Jhutti-Johal J. Sikh ethnic tick box in the 2021 Census and a question about research and methodology. University of Birmingham. 2018 [cited 2020 Oct 23].

- Crenshaw K. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color. Stanford Law Rev. 1991 Jul 1; 43: 1241–99

- Connelly R, Gayle V, Lambert PS. Ethnicity and ethnic group measures in social survey research. Methodol Innov. 2016 Jan 1; 9: 2059799116642885

- Gleeson H, Thom B, Bayley M, McQuarrie T. Rapid evidence review: Drinking problems and interventions in black and minority ethnic communities

- Grohmann S, Cuthill F. Exploring the Factors that Influence Harmful Alcohol Use Through the Refugee Journey: A Qualitative Study. 2020 Nov 10.

- Sivarajasingam V, Read S, Svobodova M, Wight L, Shepherd J. Injury resulting from targeted violence: An emergency department perspective. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2018; 28(3): 295–308

- Schick MR, Spillane NS, Hostetler KL. A Call to Action: A Systematic Review Examining the Failure to Include Females and Members of Minoritized Racial/Ethnic Groups in Clinical Trials of Pharmacological Treatments for Alcohol Use Disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2020 Sep 30

- Schick MR, Spillane NS, Hostetler KL. A Call to Action: A Systematic Review Examining the Failure to Include Females and Members of Minoritized Racial/Ethnic Groups in Clinical Trials of Pharmacological Treatments for Alcohol Use Disorder

View this report