A new study, published in The Lancet, as part of the Global Burden of Disease project, suggests that health risks associated with alcohol consumption are highest for younger age groups. The authors recommend as a result that we should introduce differential low-risk drinking guidelines, with lower guidelines for younger age groups. This is a strong claim, but does the evidence in the new study back it up?

The premise behind this study is to estimate the level of alcohol consumption at which health risks are lowest. For the majority of health conditions, this level is 0 (i.e. total abstention from drinking), as the risks of harm increase with any amount of drinking (although these increases may only be very small at low levels of consumption). However, for a small number of conditions, most notably cardiovascular disease, the evidence incorporated into this new study suggests that low levels of drinking may reduce your risks of harm. The existence of these so-called ‘protective effects’ is hugely disputed in the epidemiological literature, and the premise for this new study rather falls apart if they are not genuine.

In order to estimate the overall level of risk associated with drinking at a certain level, it is necessary to add up the risks from each of the different health conditions associated with alcohol, taking account of the prevalence of these different conditions in the population. It is also important to consider the age structure of the population as well as how drinking patterns vary between individuals.

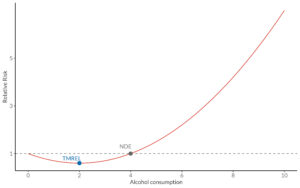

The graph below illustrates what the result of this process looks like – a curve showing the relative risk of experiencing any ill-health at different levels of drinking compared to a non-drinker. The new study identifies two key features of this curve:

- The Theoretical Minimum Exposure Level (TMREL) – the lowest point of the curve, where risk is minimised, denoted by the blue dot

- The Non-Drinker Equivalence (NDE) level – the point of the curve at which a drinker faces the same overall risk of harm as a non-drinker, denoted by the grey dot

The new study repeats this process for 204 countries around the world. So far so good – this approach is very similar to modelling work that my colleagues and I undertook to inform the 2016 review of the UK drinking guidelines and the 2019 Australian drinking guidelines review. However, where things start to unravel is when the authors decide to repeat this analysis separately by age. Because older age groups suffer more harm from cardiovascular conditions, for which low levels of drinking may be protective, while younger age groups tend to suffer a much greater proportion of their health harms through injuries, for which there are no protective affects, the TMREL and NDE estimates come out at lower levels for younger people. Indeed, the results suggest that the level of drinking at which alcohol harms are minimised for 20-24 year olds in Western Europe is 0. It is this finding on which the suggestion of lower drinking guidelines for younger people is based.

But there’s a catch. These curves represent the relative risks of harm for drinkers compared to non-drinkers within the same age group. They tell you absolutely nothing about the difference in risks between age groups or the absolute risks that people are facing as a consequence of their drinking.

To illustrate the problem: when we conducted similar analyses in 2016 we found that 25-34-year-olds drinking 4 units of alcohol every day were 27% more likely to die from an alcohol-related condition than non-drinking 25-34-year-olds. For over-55s, this difference was much smaller: they were only 4% more likely to die of an alcohol-related condition than non-drinking over-55s. However, this only tells us something about the relative risk drinkers face compared to non-drinkers within their same age group – it does not mean that drinking is riskier for 25–34-year-olds than the over-55s.

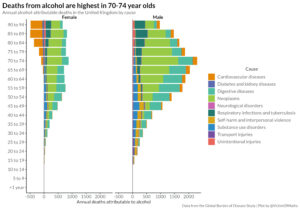

Drinking increases the risks that people already face, but these risks are much higher for older people. Data from the Global Burden of Disease project suggests that the alcohol-attributable death rate in the UK is 12 times higher in the over-55s than in 25-34-year-olds and the mortality rate from any causes is 42 times greater. So, while alcohol increases relative risk faster as consumption rises for young people, the absolute risk rises much faster for older age groups. As a result, a 4% increase in relative risk for older drinkers, applied to a risk that was big to start with, can lead to a much larger increase in absolute risk than a 27% increase applied to a small risk for younger drinkers. Simply put, a small percentage of a big number can be larger than a big percentage of a small number.

This contrast between the relative and absolute risks perspectives led us to conclude in our 2016 report that the approach used in this new study is “not well-suited to deriving age group-specific guideline thresholds”. If our aim is to minimise alcohol-related harm in society, then it seems sensible to target our efforts on the age groups who are experiencing most of that harm, which in the UK is older, not younger, drinkers.

However, this is not the only problem with this new study. There are several major methodological problems, including the fact that the authors do not account for drinking patterns. This is key because people drinking more alcohol but less frequently face greater immediate risks (e.g. from injuries) due to higher levels of intoxication than people drinking less alcohol more regularly. Beyond that, evidence suggests that even infrequent heavy drinking can remove any protective effects of alcohol consumption against cardiovascular risks.

Finally, in the press release accompanying the article, the study’s senior author is quoted as saying “our message is simple: young people should not drink, but older people may benefit from drinking small amounts”. This statement is problematic for at least two reasons.

Firstly, it fails to acknowledge the magnitude of risk involved for younger people. We face risks all the time in our everyday lives. If we were only interested in minimising those risks, we would never leave the house. The very fact that we are willing to do things like drive cars demonstrates that there is some acceptable level of risk that people are willing to take in the course of going about our daily lives. Decisions about risk are very personal; yet; the UK drinking guidelines were set in relation to a risk threshold defined to represent an ‘acceptable’ level of risk and therefore, young people choosing to drink within these guidelines are not at a substantially increased risk of suffering harm as a result of their drinking compared to non-drinkers.

Secondly, it seems to imply that older people who do not drink should be actively encouraged to consume small amounts of alcohol for the associated health benefits. This suggestion has been widely criticised in the past due to the significant uncertainty about the existence or otherwise of the protective effects of alcohol, and since then the evidence against these effects has continued to mount up. We do not know with any degree of certainty whether light drinking is beneficial or not and it would be irresponsible to make clinical decisions on this basis. Further, as 65-74 year olds have become the heaviest drinking age group according to the latest data from the Health Survey for England, we should be particularly careful about promoting public health messages that suggest drinking is beneficial in this age group.

Ultimately, the results of this study are valuable and interesting, but the conclusions that the authors have drawn from these results are extremely problematic and do not align with the wider scientific evidence.

Written by Colin Angus, research fellow at the Sheffield Alcohol Research Group within The School of Health and Related Research.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.