In this month’s alert

Government should keep the alcohol industry at “arm’s length”

In our latest publication – developed in collaboration with Professor Jeff Collin and other alcohol policy experts – we called for the UK government to keep the alcohol industry and industry-funded groups at arm’s length when developing policy.

The report – Good governance in public health policy: managing interactions with alcohol industry stakeholders – provides guidance to the new government on identifying, managing, and protecting against conflicts of interest associated with alcohol industry involvement in public health policy.

Speaking to The Guardian, IAS’s chief executive Dr Katherine Severi said:

Just like tobacco companies, alcohol companies have a long history of disrupting and delaying health policy, which is why the World Health Organization advises governments to protect against undue influence from the alcohol industry.

Dr Severi pointed to how the Scottish government was unable to introduce minimum unit pricing of alcohol for five years after legal challenges by the alcohol industry.

The report’s guiding principles state that government should:

- Acknowledge the essential conflict of interest between alcohol industry economic objectives and public health goals, in accordance with WHO recommendations.

- Establish good governance processes that promote transparency and protect health-focused policymaking from alcohol industry interference.

- Minimise interactions with industry and restrict those that occur to information exchange to support policy implementation.

- Reject partnerships with alcohol industry bodies.

Co-author Jeff Collin, Professor of Global Health Policy at the University of Edinburgh, said:

The tobacco experience clearly demonstrates that taking conflict of interest seriously is a pre-requisite for tackling the impacts of health harming industries. Nobody seriously argues that the tobacco industry should be involved in developing policies to reduce smoking, and it’s no more credible to suggest that alcohol producers would contribute positively to policies to reduce the health and social impacts of their products. Good health governance requires measures to minimise industry interference in policy-making; there shouldn’t be a place at the table for the alcohol industry.

While in opposition last year, the current public health minister Andrew Gwynne said:

If they as an industry are advocating self-regulation but at the same time incentivising higher-risk drinks through placement and advertising, do not expect the next Labour government to sit on its hands. And I’ve issued this warning directly to them already. We are considering a wide range of different interventions. If they don’t shift, the next Labour government will make them shift.

The alcohol industry body The Portman Group rejected the guidance:

This is a narrow-minded suggestion put forward by an organisation funded by the temperance movement, and it completely fails to take into account the longstanding, tangible work of initiatives funded by the alcohol industry in tackling alcohol harms, encouraging moderation and enforcing responsible marketing.

Alcohol and Cancer: Explained

In our latest Explained film, we look at:

- How alcohol causes cancer

- Which cancers it causes and the number of deaths

- The low public awareness of the link

- Why the alcohol industry wants to keep awareness low

- And what can be done to reduce cases

Our expert speaker is Professor Linda Bauld, who worked for seven years as Cancer Research UK’s cancer prevention adviser.

Do please share on social media and with relevant contacts.

Killer Tactics: How tobacco, alcohol, and unhealthy food and drink industries hold back public health progress

The alcohol, tobacco, and unhealthy food and drink industries use the same tactics to delay and prevent public health policies, a new report by the Alcohol Health Alliance (AHA), Action on Smoking and Health (ASH), and the Obesity Health Alliance (OHA) states.

The joint group is calling for Members of Parliament (MP) to reject corporate hospitality from these unhealthy commodity industries. They also highlight that gambling and fossil fuel industries seem to use this common playbook too.

The AHA’s chair, Professor Sir Ian Gilmore said:

Alcohol, tobacco and unhealthy food are the three biggest killers in our society, with alcohol alone claiming 10,000 lives in 2022—the worst on record. Our national health and frontline services are at breaking point as a result.

For too long, previous governments have worked hand in glove with these industries, leading to policies that prioritise private profits over public health. All the while people have paid the price with their lives.

If the new Labour government is serious about health as a key mission, and about cleaning up standards in Westminster, embracing the principles outlined in this report would be a good place to start.

The report gives powerful examples of the shared tactics these industries use. One of the primary tactics is to simply deny or play down the evidence of the harms their products cause. For instance, the Alcohol Beverage Foundation of Ireland stated in 2018 that: “The scientific evidence certainly doesn’t warrant the direct link between alcohol and cancer.”

All three industries consistently position themselves as part of the solution. The Public Health Responsibility Deal was a public-private partnership where alcohol and unhealthy food and drink producers would reduce the harm they caused. A decade on and every single target the unhealthy food and drink industry made has been missed.

Another key tactic all industries use is legal threats to interfere with and delay the implementation of effective policies. The Scotch Whisky Association took the Scottish Government to court for its plan to introduce minimum unit pricing. This delayed the policy for six years, meaning any deaths that would have been prevented in that time sadly weren’t. KFC has also challenged at least 43 English councils over their planning policies that would restrict new premises, and have also successfully overturned local efforts to champion children’s health in more than half of cases.

The report asks MPs to equip themselves to challenge common industry arguments that undermine public health. It also states that they should stand up for their constituents’ health and call on the government to adopt good governance policies to interact with such industries.

Hazel Cheeseman, Deputy Chief Executive of Action on Smoking and Health, said:

To preserve their integrity, maintain public trust, and ensure that public health is prioritised over private interests, MPs should avoid accepting gifts or hospitality from industries that produce harmful products. Many of these companies have clear commercial conflicts of interests and very little incentive to see sales of their harmful products fall. If you want to put out a fire don’t invite an arsonist to help.

Listen to our podcast to hear from Alfie Slade, Government Affairs Lead at the Obesity Health Alliance.

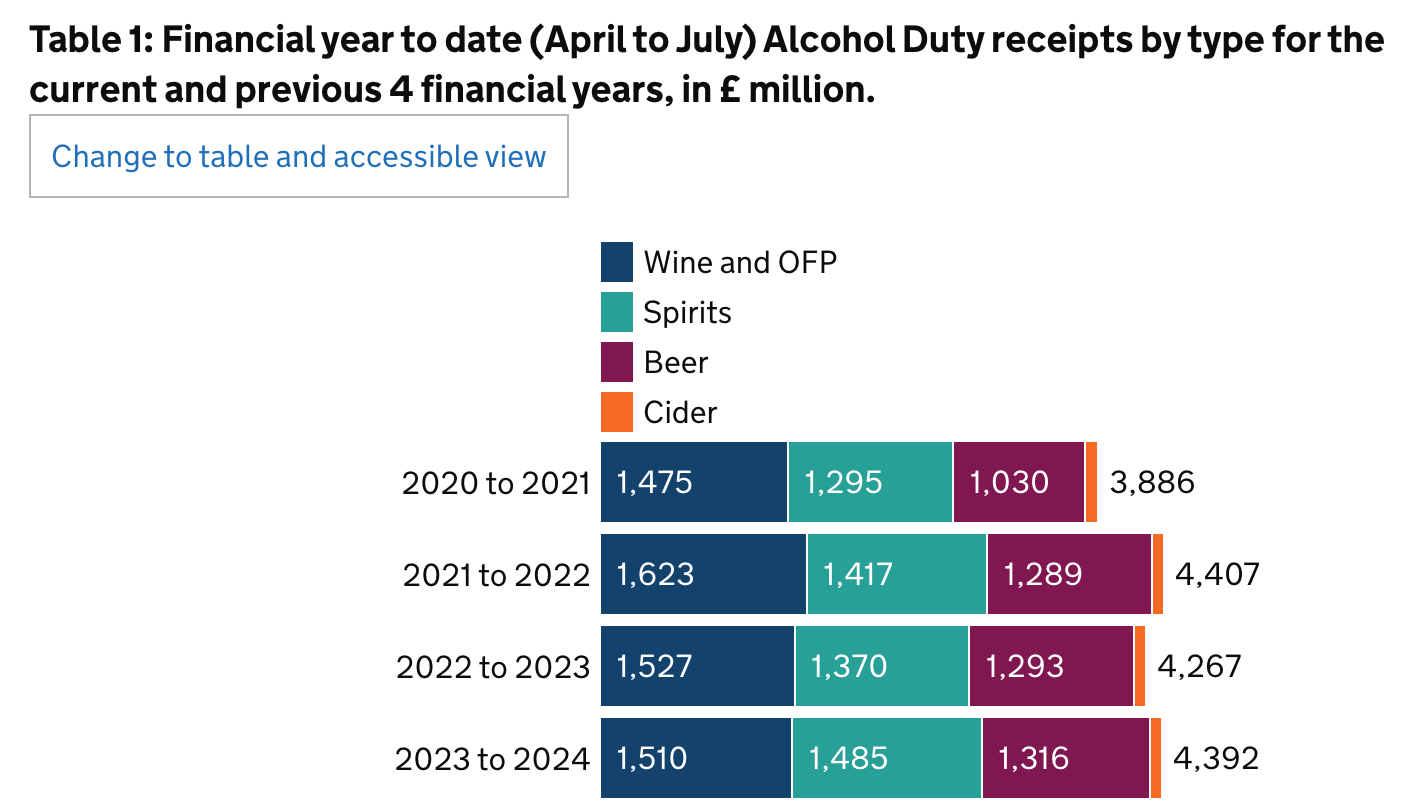

Alcohol trade groups continue to misinform on duty decisions

Writing in The Herald, IAS’s chair Dr Peter Rice hit back at industry misinformation that claimed that keeping alcohol duty in line with inflation last year led to reduced revenue for the Treasury.

Dr Rice explains that these claims are based on a short window that distorts the overall picture.

Industry trade groups have repeatedly stated that Jeremy Hunt’s decision to increase duty rates by inflation in August 2023 meant that the Treasury brought in less revenue. This argument is partly based on the discredited Laffer Curve theory (read Dr Aveek Bhattacharya’s blog ‘The dangerous mirage of the whisky Laffer curve’), and implies that increasing tax rates discourages production and therefore hits Treasury revenue.

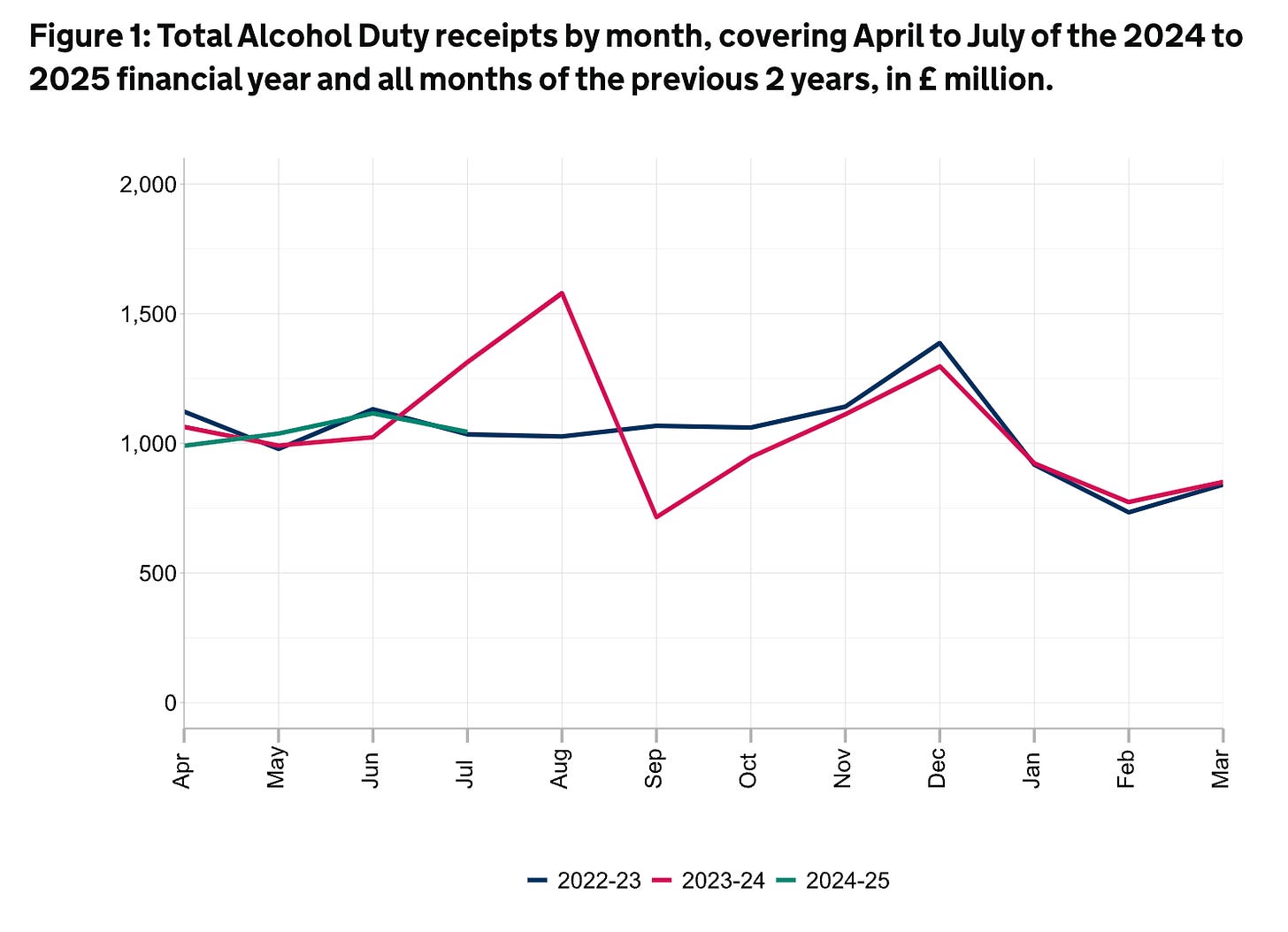

However, what trade groups fail to say is that they selectively compared a period after producers ‘forestalled’ – which means offloading more product to cash in on the lower duty rate, just before the higher rate comes in. By comparing the period after forestalling – when receipts were understandably lower than normal (see September in the figure below) – with a period when duty was frozen and producers had no motive to release product early to reduce their tax payments, trade groups can cynically claim that less revenue was raised.

As Dr Rice writes:

Instead of considering only the short window ahead of the duty increase comping into effect, as the SWA does, it is necessary to take the full picture into account by looking at the whole of 2023/24, which shows duty receipts to the Treasury are almost identical to the previous year.

As the following HMRC chart shows:

In related news, the chief executive of Alcohol Action Ireland, Dr Sheila Gilheany, has called for the Irish government to increase alcohol duty by 15% in its October budget. Alcohol has become increasingly affordability in Ireland. Dr Gilheany stated that:

A 15% rise in excise duty would go some way to simply bringing back its value to where it was ten years ago and could have a significant impact on multiple alcohol harms including drink driving.

Ryanair boss calls for two drink limit in airports

Michael O’Leary, the chief executive of airline company Ryanair, has said that passengers should be restricted to two alcoholic drinks in airports, to help tackle a rise in disorder on flights.

He told the Telegraph that:

We don’t want to begrudge people having a drink. But we don’t allow people to drink-drive, yet we keep putting them up in aircraft at 33,000ft.

According to O’Leary, crew members and other passengers have become targets for aggression and delays to flights often add to the problem by giving people more time to drink.

IAS’s chair, Dr Peter Rice, spoke to LBC’s Shelagh Fogarty about what could be done to reduce alcohol consumption in airports. You can catch up on that here at 2:05:35. Dr Rice noted that O’Leary hadn’t suggested airline companies reduce the sale of alcohol on flights.

He also pointed to an IAS report from 2018 – Fit to Fly – which recommended extending the Licensing Act to airports, so that they are required to follow the same legislation as premises in the rest of the country.

Severe shortage of Pabrinex is “an absolute disaster”

An article in the Guardian raised awareness of the severe shortage of the drug Pabrinex, a multivitamin injection which is used to protect heavy drinkers from conditions such as Wernicke’s encephalopathy and Korsakoff syndrome, which can have symptoms similar to dementia.

The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) warned in April that Pabrinex injections were likely to be in short supply until September 2025 at the earliest, and intramuscular injections were being discontinued.

Dr Marcus Bicknell, a GP specialising in addiction, described the situation as:

an absolute disaster…If this was a cancer drug there’s no way that discontinuation would be accepted.

A DHSC spokesperson said:

We know how frustrating and distressing medicine supply issues can be for patients. This government inherited ongoing global supply problems that continue to impact medicine availability, and we are working closely with industry, the NHS, manufacturers and other partners in the supply chain to resolve current issues as quickly as possible.

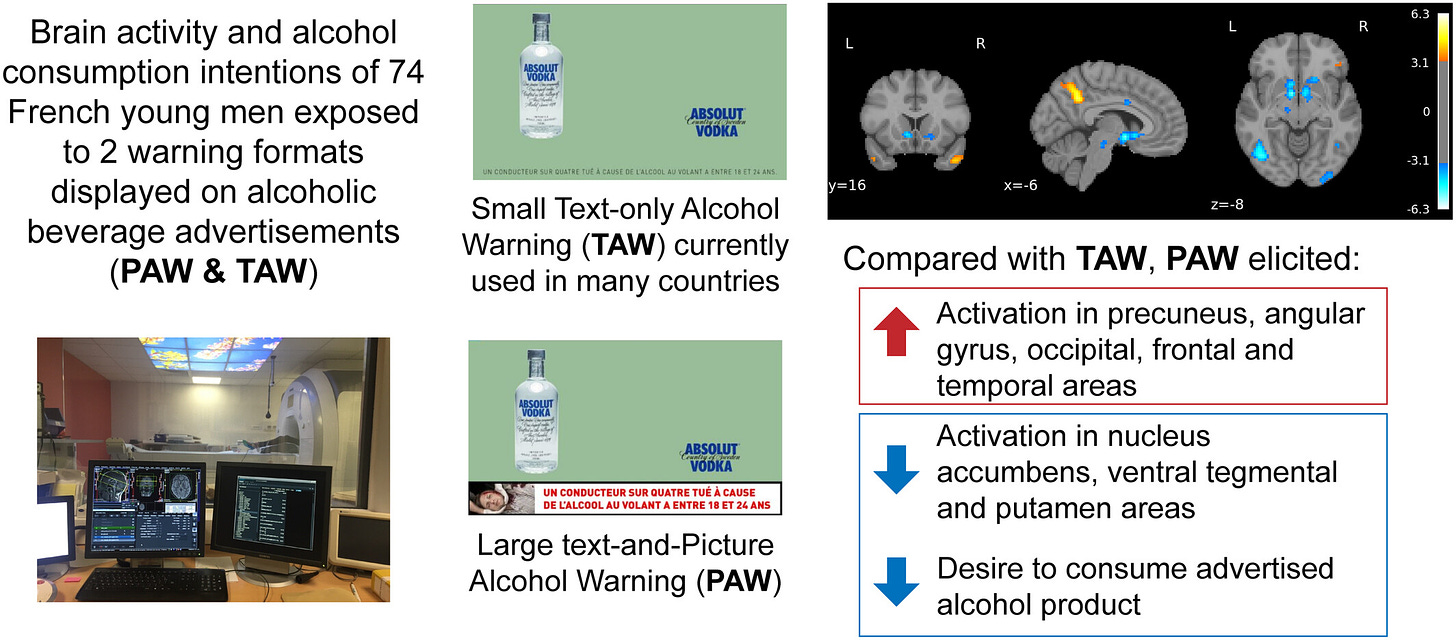

Evidence of the impact of warning labels builds

In the first study of its kind, functional MRIs (fMRI) – which look at which areas of your brain are most active – were used to analyse the brain activity of study participants when they viewed 96 alcohol ads and 96 water ads with warnings. Participants also reported whether the ads made them want to drink.

The researchers tested two types of warnings: a small text-only warning (TAW) and a larger text-and-picture warning (PAW).

Results show that the larger PAWs activated brain regions related to visual and cognitive processing more and regions related to reward and craving less compared to TAWs. Participants also reported less desire to drink after seeing PAWs.

As the authors write, this suggests that larger, more visible warnings with pictures are more effective in reducing alcohol cravings, providing useful insights for creating better alcohol warning labels. They also stated that:

It is interesting to note that our findings are very similar to the brain activation patterns generated by tobacco warnings.

Another study, in Alcohol and Alcoholism, looked at perspectives of on-product alcohol warning labels, and how they might influence purchase decisions or consumption behaviour, using 10 focus groups. The New Zealand study found that effective labels should be prominent, feature large red and/or black text with a red border, combine text with visuals, and words like “WARNING”.

The groups also said that labels should be a different colour to the bottle, be easily understood, and avoid excessive text and confusing imagery. Specific health outcomes – such as heart disease and cancer – were preferred, as they increased message urgency and relevance.

And a third article, in Addictive Behaviors, looked at what topics health warnings should address in order to be effective at informing and discouraging alcohol consumption. Participants in an online survey viewed and rated certain warning messages. As with the previous study, it was found that messages about specific health issues – liver disease, most cancer types, dementia or mental decline, and hypertension – were especially effective.

Tackling economic inactivity due to health issues will be crucial for Labour’s economic growth mission

On 23 August, Drink and Drug News published a blog by Turning Point’s Clare Taylor, in which she explained how Labour’s economic growth agenda can be supported by addressing employment barriers for those struggling with substance use.

Employment is crucial for recovery, but people with drug or alcohol issues face significant challenges in getting and keeping jobs. Successful programs, like those linking employment support with treatment centres, have shown promise.

We are now 3 years into a 10-year drug strategy, but future funding to realise the ambitions of the strategy remains uncertain. If the government continues to invest in building up skills and capacity in the sector, we can turn the tide, enabling people previously struggling with substance use to thrive within their community and workplaces.

Healthy industry, prosperous economy

In related news, The Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) published a report that highlighted how rising workplace sickness is costing UK businesses billions every year.

New analysis from the think tank reveals that the annual hidden cost of employee sickness has risen by £30 billion since 2018. Most of this increased cost (£25 billion) is from lower productivity, with only £5 billion due to a rise in sick days.

Employees now lose the equivalent of 44 days’ productivity on average due to working through sickness, up from 35 days in 2018, and lose a further 6.7 days taking sick leave, up from 3.7 days in 2018.

Workers in the UK are among the least likely to take sick days, especially compared to other OECD and European countries. They are more likely to persevere at work through sickness, which can have a productivity cost.

This can be because of a bad workplace culture, poor management, financial insecurity or just weak understanding of long-term conditions among UK employers.

– Dr Jamie O’Halloran, senior research fellow at IPPR.

IPPR is proposing a bold health plan which includes:

- Incentives: A new tax incentive for companies that commit to significant improvements in the health of their workforce, including the security, flexibility and pay of their staff, focused on SMEs.

- Regulation: A new ‘do no harm’ duty for employers, regulating them on health outcomes, not just safety inputs.

- Investment: New compulsory reporting on worker health – modelled on climate emissions reporting – to help private investors differentiate between health-orientated and health-harming businesses.

Alcohol Toolkit Study: update

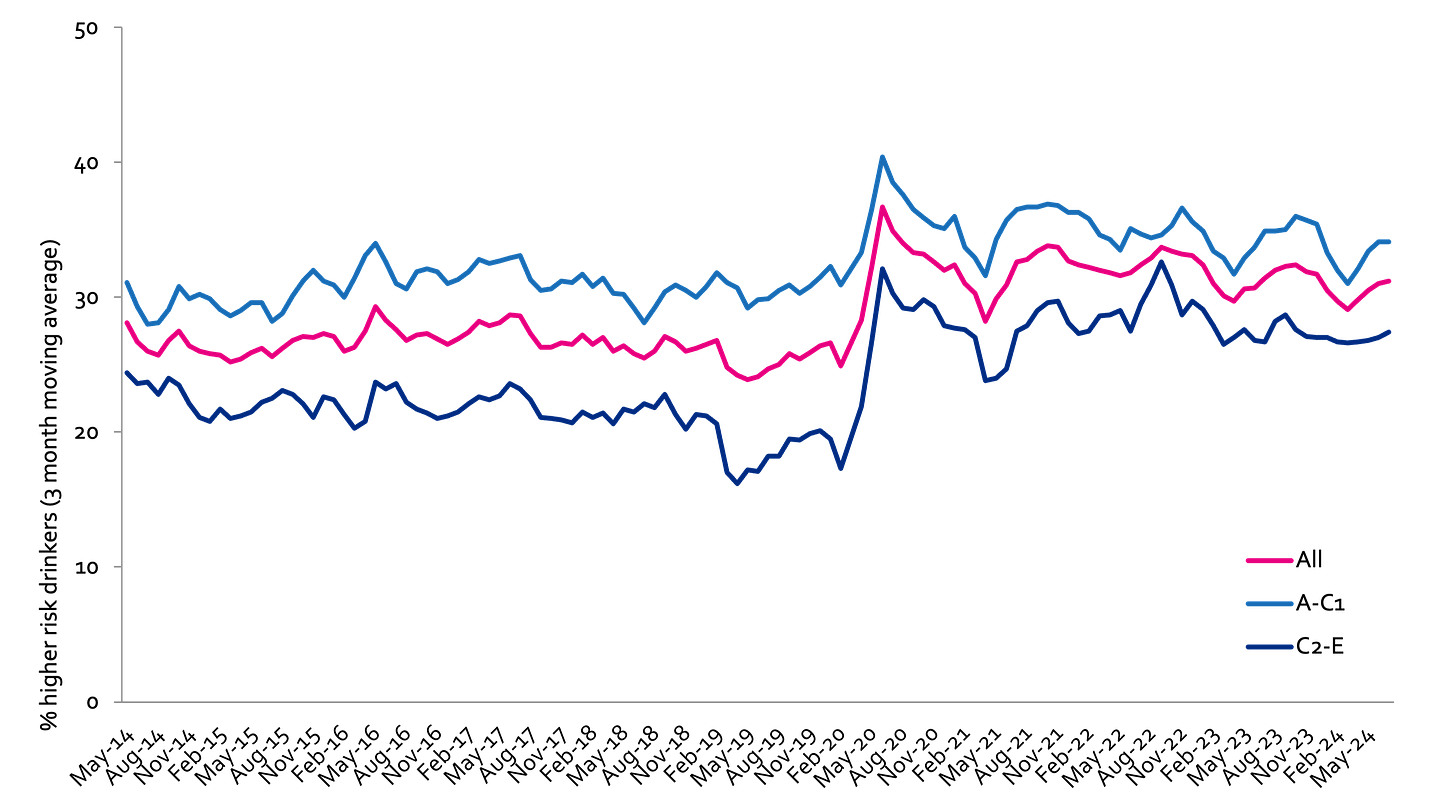

The monthly data collected is from English households and began in March 2014. Each month involves a new representative sample of approximately 1,700 adults aged 16 and over.

See more data on the project website here.

Prevalence of increasing and higher risk drinking (AUDIT-C)

Increasing and higher risk drinking defined as those scoring >4 AUDIT-C. A-C1: Professional to clerical occupation C2-E: Manual occupation

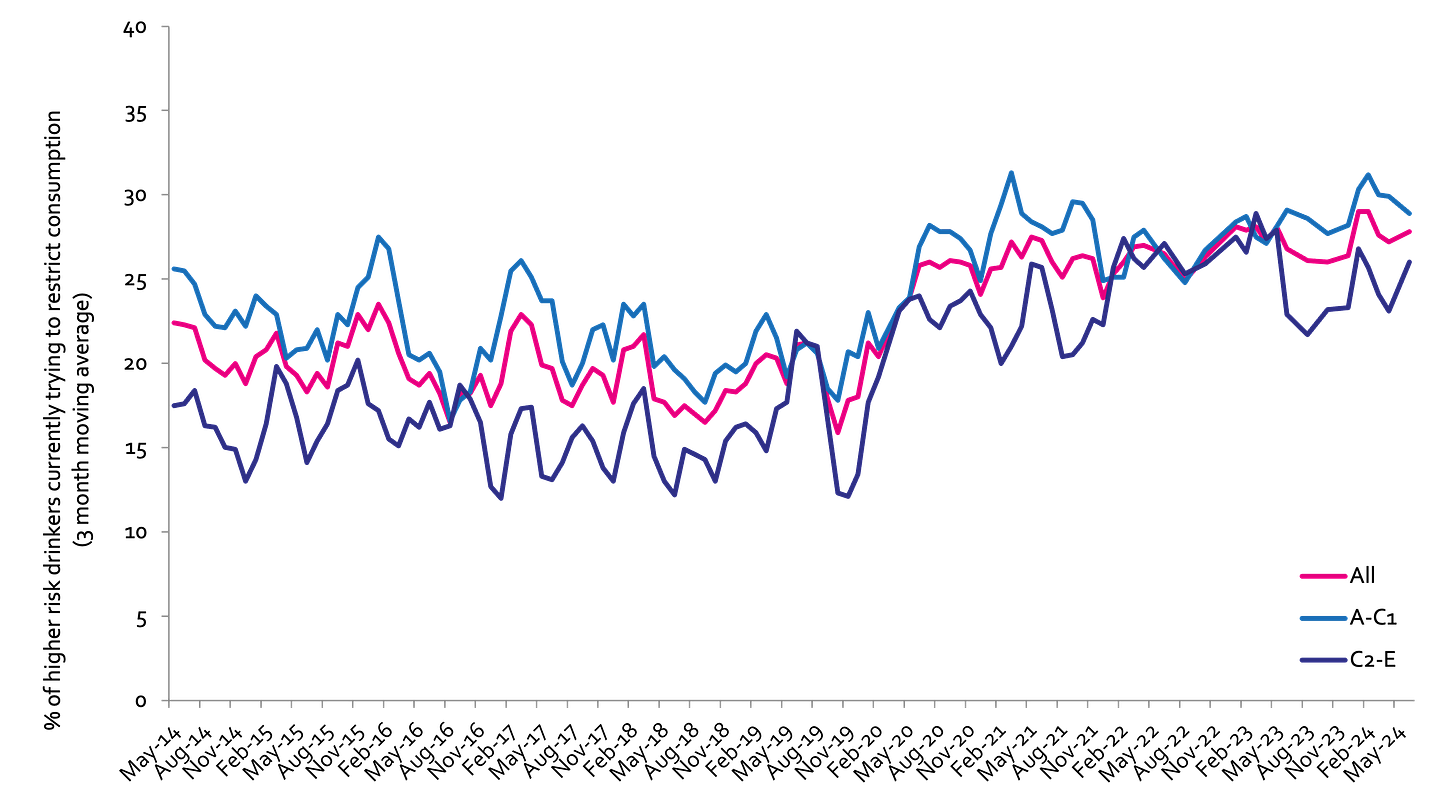

Currently trying to restrict consumption

A-C1: Professional to clerical occupation C2-E: Manual occupation; Question: Are you currently trying to restrict your alcohol consumption e.g. by drinking less, choosing lower strength alcohol or using smaller glasses? Are you currently trying to restrict your alcohol consumption e.g. by drinking less, choosing lower strength alcohol or using smaller glasses?

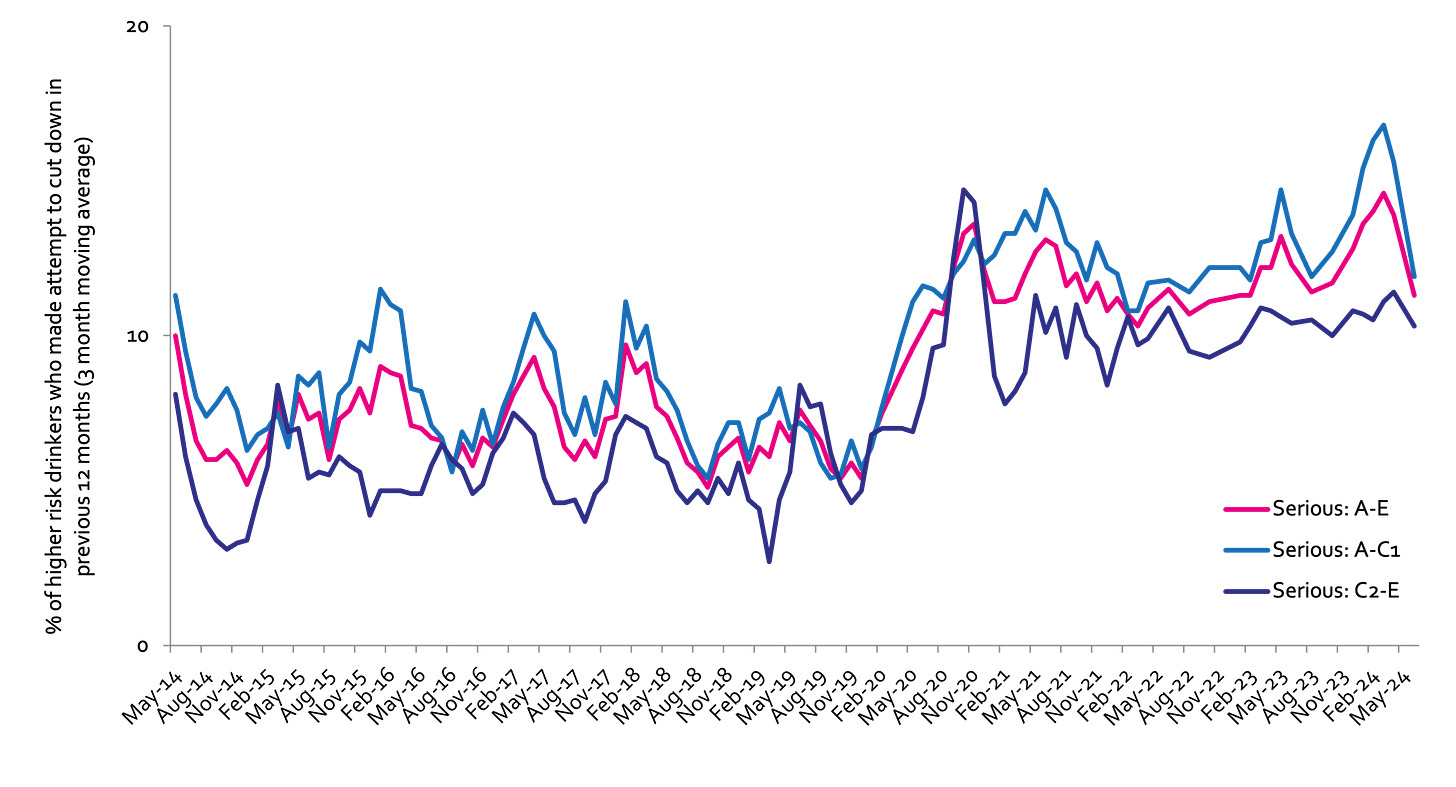

Serious past-year attempts to cut down or stop

Question 1: How many attempts to restrict your alcohol consumption have you made in the last 12 months (e.g. by drinking less, choosing lower strength alcohol or using smaller glasses)? Please include all attempts you have made in the last 12 months, whether or not they were successful, AND any attempt that you are currently making. Q2: During your most recent attempt to restrict your alcohol consumption, was it a serious attempt to cut down on your drinking permanently? A-C1: Professional to clerical occupation C2-E: Manual occupation

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

How to shift the dial on alcohol policy in Europe

Florence Berteletti –

Eurocare

Anamaria Suciu –

Eurocare