In this month’s alert

Why does the ‘alcoholism’ model dominate public discourse and how to move to understanding alcohol problems on a continuum

In our latest podcast we spoke to Dr James Morris, Research Fellow at London South Bank University, about how the model of ‘alcoholism’ evolved and led to beliefs about alcohol problems being heavily focused on the severe end of the spectrum.

Dr Morris discusses how Alcoholics Anonymous, despite helping a great many people in their recovery, reinforces this model and leads to people failing to recognise their own issues with alcohol. Discussing why this model can cause harm, Dr Morris stated:

“I think the main way it prevents progress is through ‘othering’, essentially the process of classifying alcohol problems as belonging to an ‘other’. The alcoholic stereotype is drawn on heavily for that. We see lots of heavy drinking groups point to the ‘alcoholic other’ to distance their own drinking and protect their own drinking identify.”

You can also read Dr Morris’s blog on the subject here.

Health and Social Care select committee hears from the alcohol industry on how to reduce alcohol harm

As part of its inquiry into the prevention of ill health, the Health and Social Care Select Committee held an oral evidence session on alcohol and tobacco on 06 February.

The panel giving evidence was dominated by the alcohol industry and included: Andy Tighe (British Beer and Pub Association – BBPA), Matt Lambert (Portman Group), Karen Tyrell (Drinkaware), and Sandra Butcher (National Organisation for FASD).

The session – which covered trends in alcohol consumption, the decline in youth drinking, alcohol in pregnancy, licensing, and labelling efficacy – was widely criticised by public health experts for prioritising industry representations over independent public health experts.

Professor Mark Petticrew, who has written numerous academic papers on alcohol industry misinformation, drew attention to many of the misleading statements of the panellists in his Twitter thread here. His points include:

Panellists in the tobacco session that followed were solely from the public health and medical communities. Hazel Cheeseman, of Action on Smoking and Health, highlighted the conflict of interest of including industry in harm reduction strategies, implying the session on alcohol was ill-advised. She stated that: “The tobacco industry was absolutely not part of the solution” in reducing harm from smoking. “Only by keeping them at arm’s length have we seen progress.”

The Committee has confirmed that further sessions will be held, in which public health and medical professionals are likely to be invited.

A full transcript of the session can be read here.

How does alcohol affect the brain?

A new report by six global alcohol researchers presents the evidence of how alcohol consumption affects the brain, particularly across different age groups. A launch event was hosted in the European Parliament by MEP Malin Björk, IOGT-NTO, and the European Brain Council.

The report explains that a person’s brain naturally shrinks as it ages, but drinking alcohol accelerates that process.

One of the biggest risks is to the brains of young people, particularly those under 25 as their brains are still developing. Evidence presented in the report shows that heavy and regular drinking during adolescence increases the risk of early onset dementia. In addition, alcohol dependence is developed at a young age, with two-thirds of dependent drinkers developing their dependence before the age of 25.

The prefrontal cortex in the brain is not fully developed until the age of 25 or slightly older, and this is the region associated with new learning, judgement, and behavioural control, meaning young brains are particularly vulnerable to harm. Therefore, drinking at a young age can be a key determinant of health for life.

Alcohol industry continues to lobby for duty cuts under the pretension of ‘saving pubs’

Calls by the alcohol industry and certain newspapers to freeze or cut alcohol duty have been frequent in February, with a particular focus on the need to support the pub sector ahead of the Spring Budget on 6 March.

In the i newspaper, it reported that the BBPA was publishing a manifesto demanding more government support, including lowering the VAT rate on food and drink sold in pubs, reducing the business rates, and a reduction in beer duty to “at least the European average”. However, as we explained in our report Dispelling Six Industry Myths About Alcohol Taxation, freezing and cutting duty does not help pubs. Our Communications Manager also explained this to BBC London:

The BBPA represents brewers as well as pubs, and cutting duty would help brewers, highlighting the conflicting interests of the group. This was most acutely highlighted in 2016, when a group of leading publicans wrote to the Chancellor to criticise the BBPA’s “morally flawed” campaign for a duty cut, claiming:

“The BBPA are lobbying hard on behalf of brewer members but the decrease they seek is not effectively passed down to those that make the investment and employ the people. Worse still, they are not saving a single pub with their actions.”

In a joint letter to the Chancellor published by The Sun, many producers and trade groups argued that cutting duty by 5% would increase employment by 13,000 jobs. It also stated that it would help “ensure that the Great British beer and pub sector can help contribute to wider growth and prosperity for the local high street and the wider national economy.”

Many of the arguments have also related to government revenue, with the Scotch Whisky Association and Wine and Spirit Trade Association spreading misinformation about inflationary increases in duty leading to reduced Treasury revenue. We covered the reasons for why this is not the case in our January Alert. Adding to this evidence was a recent study published in Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, on the impact of raising alcohol taxes on government revenue in Estonia, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland. The findings show that:

- Despite variations in tax revenue among countries, increases in alcohol taxation did not lead to decreased government revenue.

- Instead, higher taxes were associated with increased revenue and stagnant or decreased alcohol consumption.

- The study suggests that policymakers can raise revenue and mitigate alcohol-related harm by implementing higher alcohol taxes.

Different duty rates in pubs and supermarkets

Very few articles have publicised the idea of further differentiating on- and off-trade alcohol duty. The founder of a brewery and taproom called for this on draught beer compared to supermarket beer, arguing that it would support pubs, the economy, and sustainability targets (as draught beer is stored in casks or kegs which are reusable).

Again, part of the reason for this argument remaining rather quiet is that many of the industry groups lobbying the Chancellor represent alcohol producers that sell to both the on- and off-trade.

The UK government has already kowtowed to the industry, by freezing duty from 01 February 2024 – 01 August 2024. As the Budget in March will likely be the last fiscal event before the General Election, the government may well extend that freeze beyond August.

Reformulation of products

In more positive news, the reform of duty, which aimed to commercially incentivise the production of weaker drinks, looks like it is having that effect on some products. The Daily Mail reported that Heineken has reduced the ABV strength of John Smith’s Extra Smooth from 3.6-3.4% (moving it just into the lower duty price band). The alcohol giant claimed it was doing so for health reasons, to offer consumers weaker drinks.

Dr Sadie Boniface, Head of Research at the Institute of Alcohol Studies, doubted this:

“Although from a public health perspective it is good if alcoholic drinks are reduced in strength, there are reasons to be sceptical that Heineken has done this on health grounds. Reducing the strength of John Smith’s bitter by 0.2 percentage points saves them a considerable amount of alcohol duty, as it moves them into a much lower tax band.

“In 2022, they sold 32.9 million litres of John Smith’s in the off-trade. Using today’s duty rates, this change from 3.6 per cent to 3.4 per cent saves them in the region of £14.5 million. This is just the savings for sales in places like supermarkets, there will be further savings for sales in pubs in addition to this.”

The Chancellor of the Exchequer will present his Spring Budget 2024 to Parliament on Wednesday 6 March 2024. It usually begins at 12:30.

Scottish Government plans to continue minimum unit pricing and increase to 65p

Plans to continue setting a minimum price per unit of alcohol and to increase it by 15p will go before the Scottish Parliament for approval. If Parliament agrees, it will take effect on 30 September 2024. The increase is due to the original 50p level being eroded by inflation.

Both Scottish Labour and the Liberal Democrats welcomed the plan, meaning it is almost certain to pass through Parliament. Scottish Labour also called for a levy on retailers to tax unearned profits retailers earn from minimum pricing, with the proceeds passed directly to the NHS and efforts to combat addiction.

Alison Douglas, chief executive of Alcohol Focus Scotland (AFS), said minimum pricing was designed to reduce consumption for the roughly one million Scots who drink above the low-risk drinking guidelines, rather than the smaller group of 50,000 dependent drinkers.

Dr Sorcha Hume, Cancer Research UK’s public affairs manager, said the increase could help reduce cancer deaths:

“Not only will raising the minimum unit price of alcohol help to reduce the number of lives lost to cancer each year, but it will also reduce pressure on the NHS as well as help tackle health inequalities experienced by people in Scotland.”

The Scottish Retail Consortium welcome the increased unit price but was concerned at the prospect of an “unevidenced and unreasonable” public health levy.

Prior to the announcement, an inquiry session was held by the Scottish Parliament Health, Social Care and Sport Committee. AFS’s thread here explains the main points of the inquiry. One of the more notable moments was when Justina Murray of Scottish Families Affected by Alcohol and Drugs stated that Scottish Conservative MSP Dr Sandesh Gulhane was “possibly the only person in the room who doesn’t believe the evidence”.

Following the news, SNP MP Tommy Sheppard asked the Secretary of State for the Home Department whether he “has had discussions with his Scottish counterpart on minimum unit pricing for alcohol”. Chris Philp answered that:

“The Government notes the recent outcome report from Public Health Scotland on minimum unit pricing for alcohol. The Government will continue to monitor emerging evidence relating to minimum unit pricing with interest.”

OHID’s restructuring is a step in the wrong direction for public health

In the BMJ, Clare Bambra, professor of public health at Newcastle University and Sir Michael Marmot, professor of public health and epidemiology at University College London, discussed concerns about recent cuts to the UK’s public health infrastructure amidst rising health inequalities.

They say the cuts to the Office for Health Disparities and Inequalities (formally Public Health England) come at a crucial time as the UK public inquiry into COVID-19 is still ongoing, examining the adequacy of the country’s pandemic response and public health infrastructure.

They emphasise that the UK entered the pandemic with health inequalities on the rise and life expectancy stalling, particularly for the most deprived populations. They link these issues to austerity measures implemented since 2010, which have disproportionately affected low-income households and deprived areas.

Professors Bambra and Marmot conclude that improving public health funding is vital to addressing health inequalities and life expectancy, and for better preparedness for future pandemics.

Increasing support for government intervention and the ‘Nanny state’

A number of articles in February focused on government intervention and the importance of tackling health inequalities.

Sixty senior health experts wrote to the Chancellor urging him to address public health in the Spring Budget, reported in The Times. The letter, which was coordinated by the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR), states that poor health is one of the greatest threats facing Britain today, particularly due to its damage to the economy, from the size and strength of the labour market to productivity, growth and GDP.

The vast majority of health conditions contributing to economic problems are driven by poor diets, alcohol and tobacco consumption. Recent YouGov polling also indicates strong public support for greater state intervention to promote healthier lifestyles.

Dr Aveek Bhattacharya of the Social Market Foundation wrote in the Financial Times that the UK has seen a ‘surge’ in public health interventionism with the tobacco ban and Labour’s Child Health Action Plan, and Scotland’s plans to retain MUP.

James Kirkup, the former Director of the Social Market Foundation, argued in The Spectator that “the nanny state is coming. Look busy.” He said that industries that would be affected by interventionist public health policies should act to reduce harm before they are inevitably pushed.

And the political writer and broadcaster Matthew Parris, who was a Conservative MP from 1979 to 1986, wrote in The Times that the Tory right has never understood freedom. He explored the contradictory nature of criticising the ‘nanny state’ as an infringement on freedom, while not advocating for freedom in other areas, such as for same-sex marriage, and the freedom to protest.

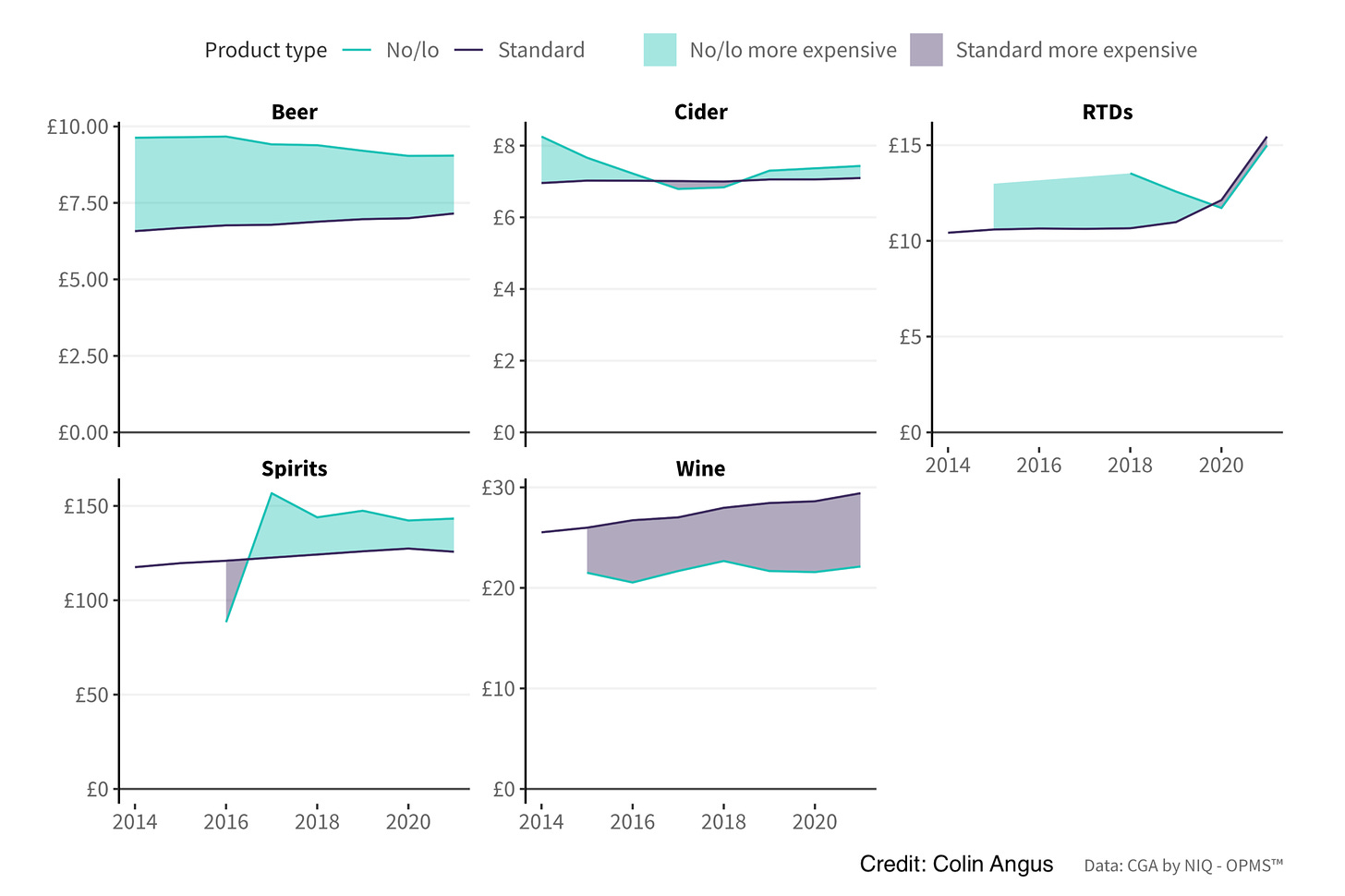

Do no and low alcohol drinks really cost more than alcoholic products?

Health economist Colin Angus discusses new research from the Sheffield Addictions Research Group, regarding the price of no and low alcohol drinks. He explains that they do tend to be more expensive, despite alcohol duty not being applied to products up to 1.2% ABV. Although for branded products, their zero-alcohol counterpart tended to be cheaper, for instance, Guinness and Heineken 0.0.

Angus writes that de-alcoholising products can be very expensive and zero-alcohol products are often packaged in smaller pack sizes, increasing their expense.

The high price is likely to be a major factor in why these products are still a very small proportion of the alcohol market, just over 1%.

The Group’s research also shows that beer was by the far the most popular no/lo product, accounting for three-quarters of sales. The price paid was £9.04 per litre compared to £7.15 for standard beer. Zero alcohol spirits were also more expensive. On the other hand, zero-alcohol wine was 25% cheaper than alcoholic wine.

Responses to Parliamentary Questions highlight lack of government progress

In responses to written Parliamentary Questions from Labour MP Rachael Maskell, the Public Health Minister, Dame Andrea Leadsom, outlined the UK government’s approach to reducing alcohol harm.

In one response, Leadsom stated that the government is committed to supporting “the most vulnerable and at risk from alcohol misuse”, partly by raising awareness of the drinking guidelines, “by encouraging producers to reflect the guidelines on the labels of alcoholic drinks”.

Not only is there limited evidence that labelling and education are effective ways of reducing alcohol-related harm, but the alcohol industry has dragged its heels in implementing the up-to-date drinking guidelines on labels. Despite the guidelines being introduced in 2016, a study in 2022 found that a third of products still did not have the correct guidelines. This is why the regulation of alcohol labelling should not be under the control of the industry body the Portman Group.

In a second response, Leadsom highlighted that the UK was actively involved in the development of the World Health Organization’s “plan to strengthen the implementation of the Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol”. Despite this statement, many of the policies detailed in the Strategy have barely been considered by the UK government, such as restrictions on alcohol marketing, introducing minimum pricing, or banning promotions and discounts.

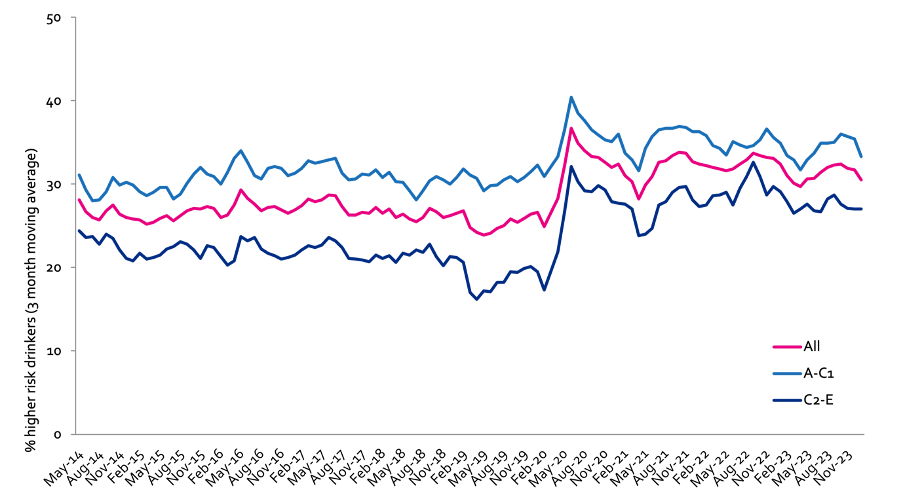

Alcohol Toolkit Study: update

The monthly data collected is from English households and began in March 2014. Each month involves a new representative sample of approximately 1,700 adults aged 16 and over.

See more data on the project website here.

Prevalence of increasing and higher risk drinking (AUDIT-C)

Increasing and higher risk drinking defined as those scoring >4 AUDIT-C. A-C1: Professional to clerical occupation C2-E: Manual occupation

Currently trying to restrict consumption

A-C1: Professional to clerical occupation C2-E: Manual occupation; Question: Are you currently trying to restrict your alcohol consumption e.g. by drinking less, choosing lower strength alcohol or using smaller glasses? Are you currently trying to restrict your alcohol consumption e.g. by drinking less, choosing lower strength alcohol or using smaller glasses?

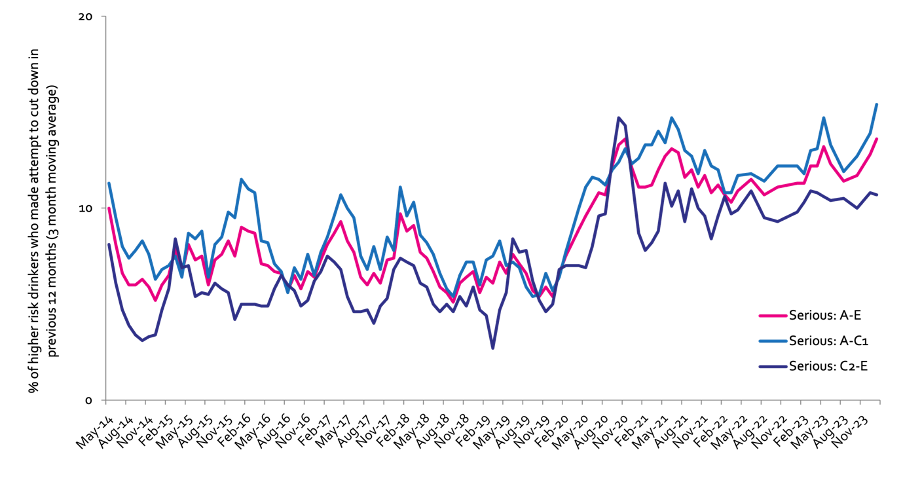

Serious past-year attempts to cut down or stop

Question 1: How many attempts to restrict your alcohol consumption have you made in the last 12 months (e.g. by drinking less, choosing lower strength alcohol or using smaller glasses)? Please include all attempts you have made in the last 12 months, whether or not they were successful, AND any attempt that you are currently making. Q2: During your most recent attempt to restrict your alcohol consumption, was it a serious attempt to cut down on your drinking permanently? A-C1: Professional to clerical occupation C2-E: Manual occupation

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

Gambling industry harms and parallels with the alcohol world

Will Prochaska –

Coalition to End Gambling Ads