On this page

Otherwise known as Driving Under the Influence (DUI) or Driving While Intoxicated (DWI), drink-driving in the UK is defined as the act of being in possession of a recognised mode of transport (a motorised vehicle such as a car, truck, boat, etc) while under the influence of alcohol. It can become a criminal offence when a subject is caught with blood levels of alcohol in excess of a legal limit. A conviction for drink-driving may not necessarily involve driving a vehicle; you can also be prosecuted in charge of a parked vehicle and/or failing to cooperate with the police in taking a preliminary roadside breath test.

As well as being against the law, drink-driving in excess has also scientifically been shown to greatly increase the risk of injury to all parties on the road. Despite a steady decline in the annual number of drink-driving accidents and fatalities to the lowest levels since records began, it remains the case that thousands of people are injured on the roads by drivers who drink, and the number of fatalities has stayed largely unchanged since 2010. In 2016, the drink drive limit was the subject of a campaign to lower it, featuring a broad coalition of non governmental organisations. For more information, please view our lower the limit campaign page.

The consumption of alcohol can have disruptive impact on other modes of transport, including air travel – as our Fit to fly report found – and on waterways too: boaters may be prosecuted under the Merchant Shipping Act 1995 if their actions on the water are seen to be endangering other vessels, structures or individuals and they are under the influence of alcohol.

Facts and stats

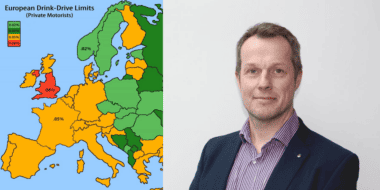

- England and Wales: The drink drive limit in England and Wales is 80mg/100ml of blood (or 35 micrograms of alcohol per 100 millilitres of breath) – set by the UK’s first Road Safety Act 1967.

- Scotland: Reduced to a 50mg/100ml limit in December 2014 (or 22 micrograms of alcohol in 100 millilitres of breath).

- Northern Ireland: In 2016, NI legislated for a 50mg/100ml limit, but this is yet to be enacted.

- All other European countries have a limit of 50mg or lower.

What are the drink drive limits in UK and Europe? by The Institute of Alcohol Studies – Download this chart

- Men are four times more likely to be involved in a drink drive collision than women, and four times more likely to be injured. (DfT)

- Almost all of those killed in drink drive collisions (230 in 2023) are male. (DFT)

Drink drive collisions by sex by The Institute of Alcohol Studies – Download this chart

- Young drivers, especially under 25, have far higher drink-drive collision rates per mile driven than older groups, showing the elevated risk even after accounting for how much they drive.

Drink drive collisions by age by The Institute of Alcohol Studies – Download this chart

- Car occupants are much more likely to be killed in drink drive collisions, however cyclists, pedestrians, and motorcyclists are also killed every year.

- Among vehicle driver fatalities with a BAC of 10mg/100ml or higher, almost half (45%) had very high levels of alcohol in their system (150 mg or more), while around one in three (30%) were below the legal limit.

Drink drive fatalities by BAC levels by The Institute of Alcohol Studies – Download this chart

- Over time, the proportion of road accident fatalities caused by drink driving has reduced significantly.

- In 1979, more than a quarter of road accident fatalities occurred as a result of drink-driving.

- Since 1989, drink-driving has accounted for 12–18% of all GB road deaths.

- Drinking alcohol affects your reaction times, coordination, concentration, judgement, and vision.

- Impairment of critical driving functions begins at lower BACs and most people are significantly impaired at 50mg. (Fell and Voas, 2009)

- At a BAC of 70mg (within the UK limit), drivers show significant lane weaving and slower, less accurate reactions, yet rate their driving ability the same as when sober (Garrisson, 2022).

- Crash risk rises sharply with even small amounts of alcohol – drivers with a BAC of 20-50mg are at least three times more likely to die in a crash; risk rises to six times at 50-80mg and 11 times at 80-100mg. Younger drivers face even greater relative risk at all positive BACs. (NICE, 2010)

- The effect of lowering the BAC limit (in terms of reducing harm) is likely to be dependent on increasing the public’s awareness and understanding of BAC limits and rigour of enforcement strategies. (NICE, 2010)

- A UK study estimated that had the limit been lowered from 80mg to 50mg/100ml at the beginning of 2010, then in every year between 2010 and 2013 about 25 lives would have been saved and 95 people saved from serious injury. (PACTs, 2015)

- Modelling for England and Wales – lowering the limit from 0.08 to 0.05 could reduce road fatalities by around 6–7% (saving thousands of casualties annually), though estimates carry some uncertainty. (NICE)

- Evidence from multiple countries shows that moving from 100mg to 80mg lowers alcohol-related fatalities, and reducing from 80mg to 50mg also produces significant benefits – a high-quality European study found an 11.5% drop in alcohol-related deaths among 18–25-year-olds. (NICE)

- In Australia when the limit was reduced from 80mg to 50mg, fatal accidents fell by 18% in Queensland and 8% in New South Wales. (NICE)

- Sweden adopted a 20mg limit in 1990 – and the number of drink-driving accidents fell. A 1997 study on the change showed that a 20mg limit reduced fatal crashes by 9.7%, with a 7.5% reduction in all crashes. Crucially, crashes also fell among the most serious drink-driving offenders. (BBC)

- When Scotland lowered its limit to 50mg in December 2014, police figures showed a 12.5% decrease in drink drive offences in the first nine months. (BBC)

- Scotland’s lower limit did not lead to a reduction in fatalities, with researchers pointing to a lack of cheap, alternative transportation and weak enforcement driving the lack of impact. (Francesconi & James, 2021)

- The number of roadside breath tests has more than halved since 2009, yet the proportion of tests that were positive or refused has risen from 10–12% in the mid-2010s to around 16–17% in recent years. (Home Office)

Breath test figures and failures by The Institute of Alcohol Studies – Download this chart

- Random breath testing (RBT) is proven to be one of the most effective deterrents to drink-driving, especially when highly visible and well-publicised. It allows police to stop drivers at random without suspicion, increasing the perceived risk of detection. Evidence from Australia shows RBT reduces fatal crashes by 13–36% when implemented at scale. (NICE)

- Sobriety checkpoints operate by stopping vehicles at fixed points to test drivers for alcohol; may be applied randomly or to all vehicles. Studies in the US and Europe indicate that regular, high-visibility checkpoints reduce alcohol-related crashes by 17–25%. The effectiveness depends on frequency, unpredictability, and public awareness of enforcement activity. (NICE)

- £754m: the estimated cost of drink-drive accidents with casualties across the UK, where the driver was found to be above the 80mg limit (2014: This figure was calculated by multiplying estimated fatal, serious and slight drink drive accidents by the average valuation of the cost of each type of accident, based largely on willingness to pay studies and surveys (e.g. of emergency service providers, insurance companies))

- The estimated personal financial cost of drink-driving for the first time is between £20,000 and £50,000 (IAM, 2013)

- 60% of adults who have encountered drunken passengers during a flight (IAS, 2018)

The following recommendations are taken from the 2021 PACTS report and the BMA’s 2025 consensus statement on drink driving:

- Lower the legal blood alcohol content (BAC) limit for driving to 20mg/100ml (0.02%) for new and commercial drivers, and 50mg/100ml (0.05%) for all other drivers, with the ambition to reach 20mg/100ml for all drivers as soon as possible.

- Raise public awareness about the new BAC limit and current drug driving laws

- Mandatory breath testing powers for the police and the reduction in enforcement levels to be reversed

- Increased penalties for drivers who combine drink and drugs

- Specialist rehabilitation courses for those with mental health and alcohol problems

- Increasing alcohol and drug treatment service capacity and capability

- Reforming the High Risk Offender Scheme

- That the government pays more attention to drink driving in alcohol harm and night-time economy policies

Briefings

Reports

Blogs

Why England and Wales need a lower drink drive limit

26th August 2025

None for the road: Why lowering drink drive limits didn’t lower road traffic collisions

25th August 2021

What can we learn from repeat drink drivers’ attitudes and beliefs about drink-driving?

23rd February 2021

Drink-driving could soar as pubs reopen in July

13th July 2020

Revoking the ‘License to Drink’: Emerging evidence on mandatory sobriety

26th June 2020

Alcohol control policies and alcohol-related traffic harm in Lithuania: a short summary of a success story

24th February 2020